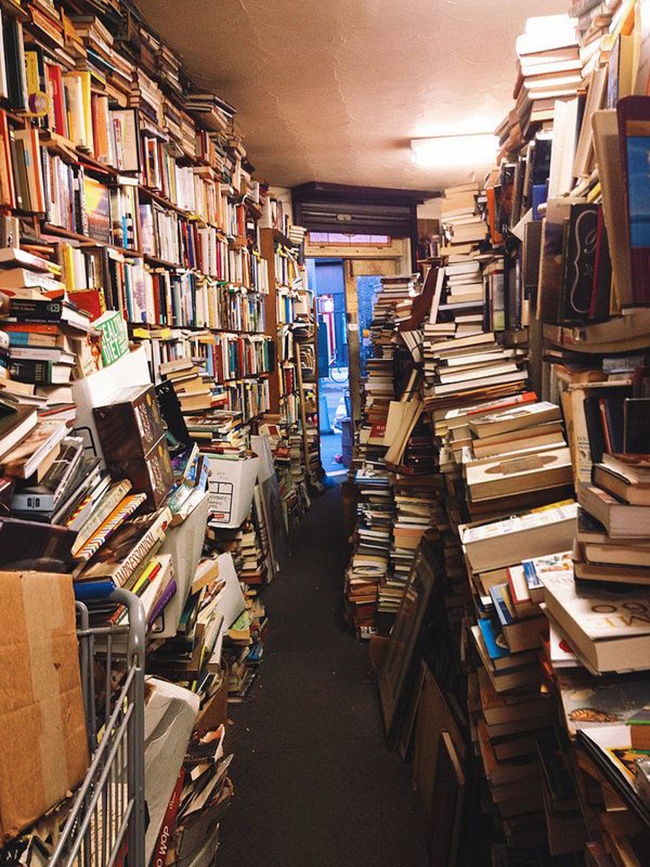

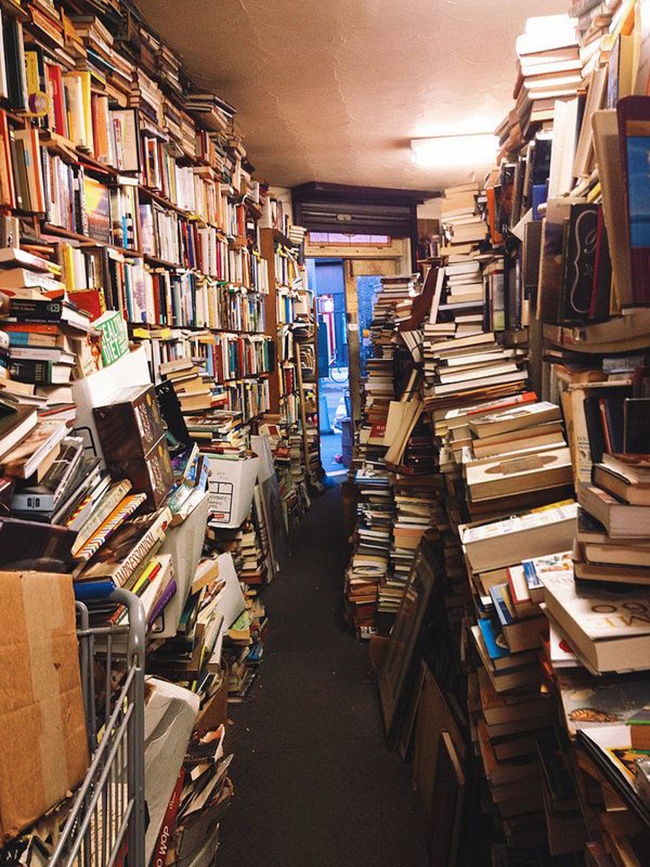

Getting something from Community Bookstore felt more like spelunking than shopping. The second-hand bookstore, located on a street corner in Brooklyn, was a dark, cavernous space filled with worn paperbacks, dusty toys, and vintage records. The shop's owner, John Scioli, was a self-described hoarder unable to turn away book donations. Inside of his shop, piles of musty books stood waist-high, some half toppled, and items were stacked on top of each other at awkward angles, making a trip down an aisle feel like "high-stakes Jenga." The shop was so densely packed that light from the buzzing fluorescent tubes overhead never penetrated to all corners. Scattered books underfoot buried the worn grey carpeting underneath. It was impossible to find anything here — you had to aimlessly browse or ask Scioli for assistance. He had a Dewey Decimal System inside his head that allowed him to find anything. Just don't ask for a recommendation. In a crotchety interview with Gothamist, the white-whiskered bookseller dryly said: "I hate [when people ask for book recommendations]. 'What should I get my father for Father's Day?' I don't know your father."

In an era of minimalist shopping spaces and customer-centric service, Community Bookstore was a strangely beloved institution. It had no traditional storefront or signage, and the only worker, the owner, kept unpredictable hours. Yet, it was a fixture of the community, cherished by "regulars, neighbors, dinner dates, bookworms, French transplants, Spanish tourists, Italian grandmothers, and authors acclaimed or otherwise." Like an old-school tailor or barber, Scioli saw generations of people grow up in the Brooklyn neighborhood. Those who initially stopped by as children to play with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle action figures later came in as adults to buy bedtime storybooks for their children. When Scioli closed his business and retired in 2015, the store generated an outsized amount of press. The New York Times wistfully wrote of it: "The Community Bookstore is not the kind of place one goes for the latest bestsellers, literary magazines, a coffee, or an author talk. It is a place to rummage and ruminate, a place for treasure hunters and lost souls as much as bibliophiles."

Americans hold the idea of bookstores near and dear to their hearts, although independent booksellers have seen better days. Around the turn of the 20th century, New York City's Fourth Avenue was home to nearly fifty bookstores, many with used hardbacks stuffed into rollable carts displayed outside of their front windows. There were once so many bookstores located between Union Square and Astor Place, the district was nicknamed Book Row. But after the Great Depression, skyrocketing rents, and those original booksellers retiring and then dying (with no one to take their places), the bookstores that used to be a fixture of literary Manhattan faded away. Today, only one bookstore from Book Row is still standing — The Strand, now headquartered on Broadway in the East Village, where it moved in 1957 to escape high rents. Insiders say that The Strand has only survived because it's a family's passion project. "[T]he Strand is, when you get down to it, a real-estate business, fronted by a bookstore subsidized by its own below-market lease and the office tenants upstairs," Christopher Bonanos wrote in New York Magazine. "The ground floor of 828 Broadway is worth more as a Trader Joe's than it is selling Tom Wolfe. When a business continues to exist mostly because its owners like it, the next generation has to like it just as much. Otherwise, they'll cash out. If Nancy stays, the Strand stays. If her kids do, too, it stays longer. Simple as that."

Keep reading