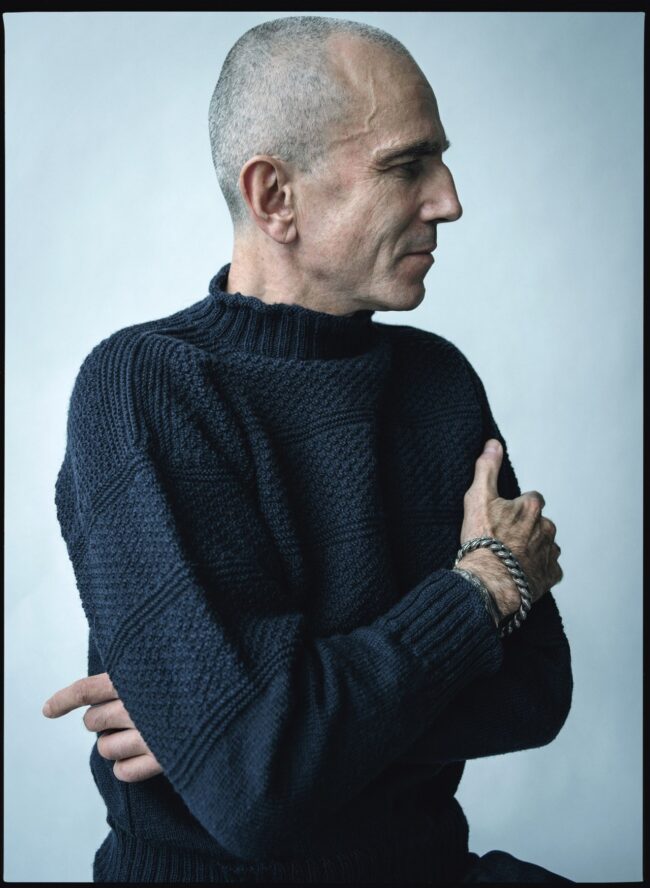

I was having dinner with Nicholas Templeman a few years ago at Besharam, a small Indian restaurant located on the outskirts of San Francisco. Over spicy vegetarian curries and delicate semolina puffs, we discussed how the British shoemaking trade has changed over the years. I told him I'd recently spoken with Daniel Wegan and Emiko Matsuda, two bespoke shoemakers who, like him, left prestigious West End firms to launch their own shoemaking businesses. Wegan and Matsuda's operations are modest, with no advertising budgets, celebrity endorsements, or visible shopfronts. When I asked how customers typically find them, they said, "Instagram." "That was a big part of why I left John Lobb when I did," Templeman told me. "At the time, some independent makers in Japan made good use of social media, but not many people in the UK. Even the big shops were barely visible online. With the rise of social media sites like Instagram, I felt this was a good time to become independent."

In the last twenty years, the British bespoke trade has changed dramatically along two fronts: skyrocketing rents and the loss of skilled labor have made it more difficult for larger firms to earn profits and maintain quality. Simultaneously, the internet has created a more informed consumer. These customers, who can be described as "shoe mad" enthusiasts, scour blogs and forums for niche details about shoemaking that few people know or care about. Like Athenian philosophers or Tibetan monks, they use the dialectical process to arrive at truths about handwelting and Goodyear welting, Celastic and leather stiffeners, and the specialized construction techniques that go into the uppers and soles of shoes, such as split-and-lift sewing and fiddleback finishings. For men who have succumbed to the allure of craft, celebrity endorsements and shallow, romantic accounts of the bespoke process are not enough. They want to know the intricate, technical details of shoemaking.

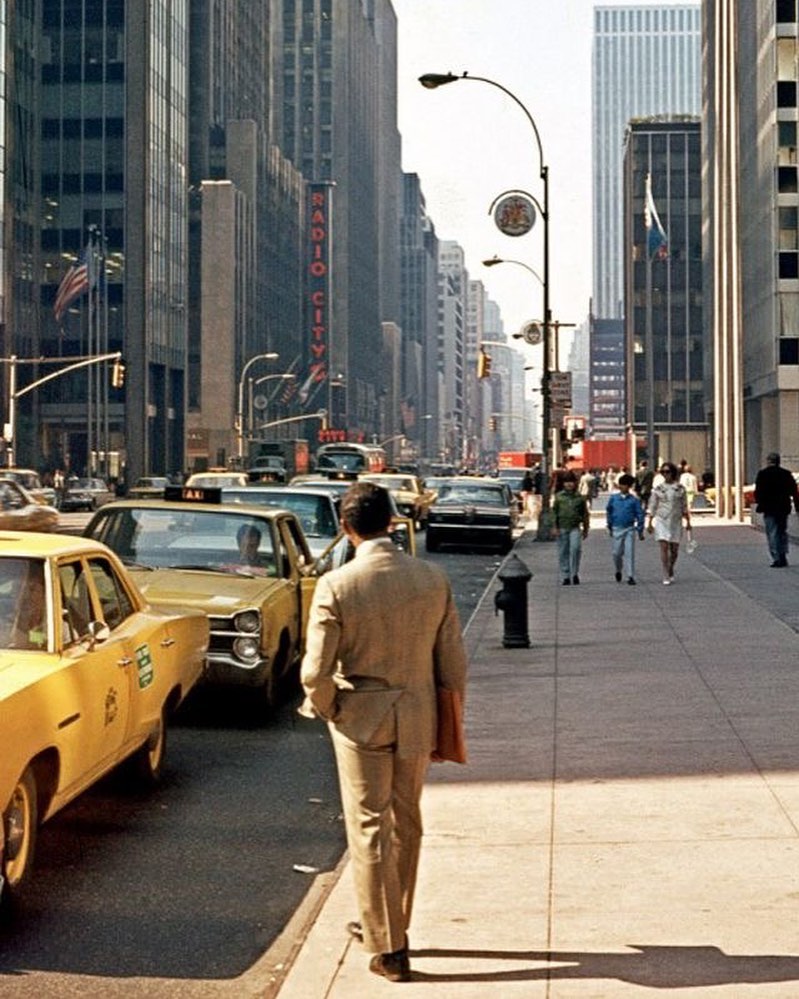

These changes have impacted the British bespoke trade in some crucial ways. In the mid-19th century, Punch co-founder Henry Mayhew published a seminal study on London's laboring classes. He estimated the city had 28,574 shoemakers (or "bootmakers" if you prefer the Queen's English) in the 1840s, making it the third most popular occupation. By the end of the century, improvements in ready-made footwear dramatically shrank this number to around 3,000, consolidating many workers into a handful of large firms. Among these businesses were gilded names such as John Lobb, Peal & Company, and Henry Maxwell, who built reputations by making shoes for presidents and pioneers, authors and actors, titans of industry, and other members of the ruling class. They also reaped the benefits of a fawning press. After reading enough breathless prose, wealthy men convinced themselves that spending thousands on shoes "would itself be an act of poetry," as my friend Réginald-Jérôme de Mans put it.

Keep reading