You used to have to muscle your way into stores and stand in long lines to take advantage of Black Friday promotions. Nowadays, everything is online, so you can shop from the comfort of your own home. The difficulty, of course, is that you're then swamped with possibilities, making it impossible to know what to buy. To make the landscape a little easier to navigate, I round up some of my favorite Black Friday promotions every year and post them here, along with a selection of notable picks at each store. These guides are designed to cover almost every budget—from relatively affordable basics to designer items—so there's something for everyone. Here's this year's list organized by increasing order of price with a smattering of miscellanea at the end.

J. CREW: 50% OFF EVERYTHING; NO CODE NEEDED

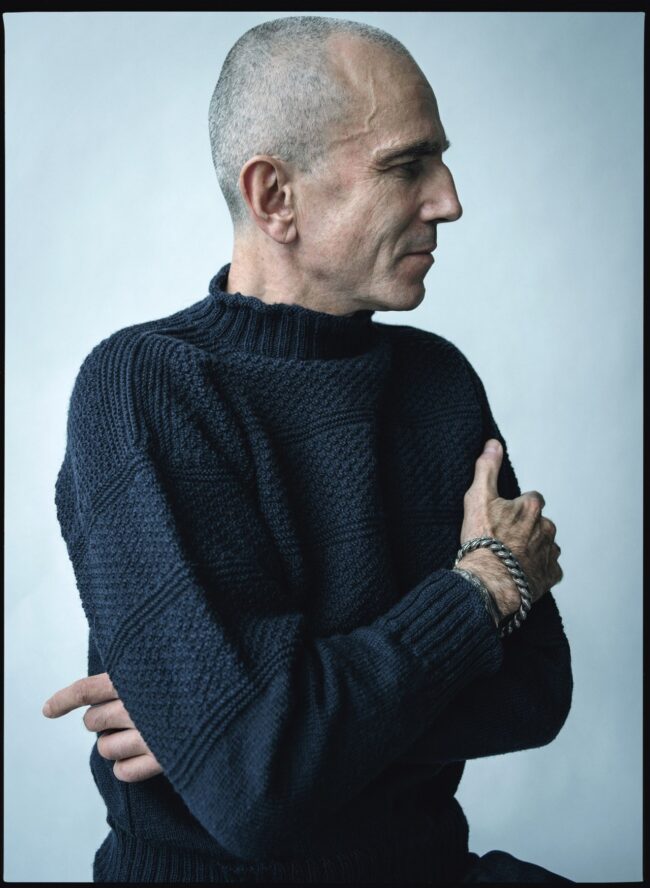

In 2020, when J. Crew filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, I wrote an op-ed for The Washington Post about how this preppy brand plays an important role in the menswear market. For many guys, J. Crew is their entry point into building a better wardrobe. The company's prices are relatively affordable, and the designs are fairly classic. The company sells things such as chambray work shirts, field jackets, and flat-front chinos—things that look good on almost everyone. However, the departures of Jenna Lyons and Frank Muytjens in 2017 casted a shadow of uncertainty. Speculation surfaced about plans to transform J. Crew into a version of The Gap, potentially distributed through Amazon. So it was a relief when the company ousted the old management and design team, replacing them with Brendon Babenzien, the new Creative Director, who has steered the company clear of such a fate, injecting renewed vitality into this iconic label.

Keep reading