Excited to Wear This Spring

It is a grim feature of modern life that we treat downtime as a pit stop between bursts of usefulness. In the United States, where the Protestant work ethic took the deepest root, even Sabbath observance was shaped by the belief that unproductive time required moral justification. Writing in the early 1930s, Bertrand Russell warned that “immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous.” By 1948, the German philosopher Josef Pieper offered a more forceful philosophical defense of leisure. His book Leisure: The Basis of Culture, published in the wake of one of the largest labor strike waves in US history, pushed back against what he called the tyranny of “total work,” a condition in which the modern human is reduced to their measurable productivity.

If leisure needs any justification at all, it can be found in the breakthroughs it enables: Darwin doing his deepest thinking during long walks at Down House, Beethoven composing "Symphony No. 6" in the countryside, Newton developing the foundations of calculus while on a two-year leave from Cambridge. But framing leisure in terms of output, or even as a way to rejuvenate us for labor, still reduces it to an instrument of the state or market. Instead, Pieper argues that leisure is a necessary condition for the soul. The Greek word for leisure, scholē, is the root of our word school—not a site of vocational training, but a space for contemplative stillness. Leisure ensures that “the human being does not disappear into the parceled-out world of his limited work-a-day function, but instead remains capable of taking in the world as a whole, and thereby to realize himself as a being who is oriented toward the whole of existence.”

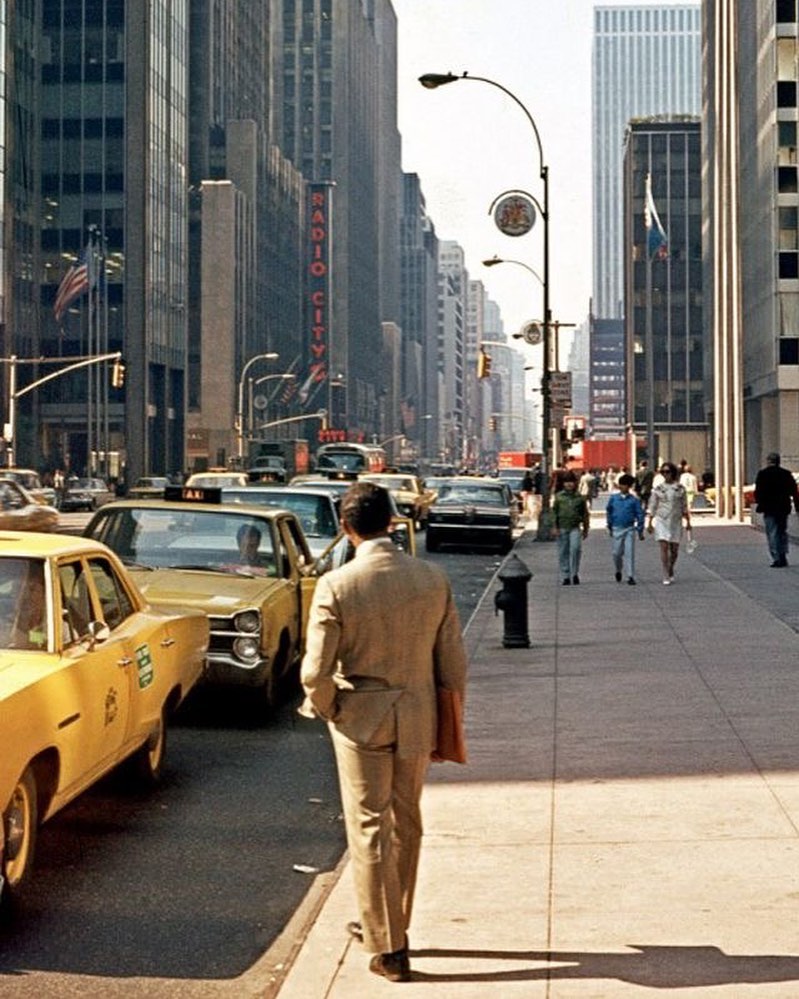

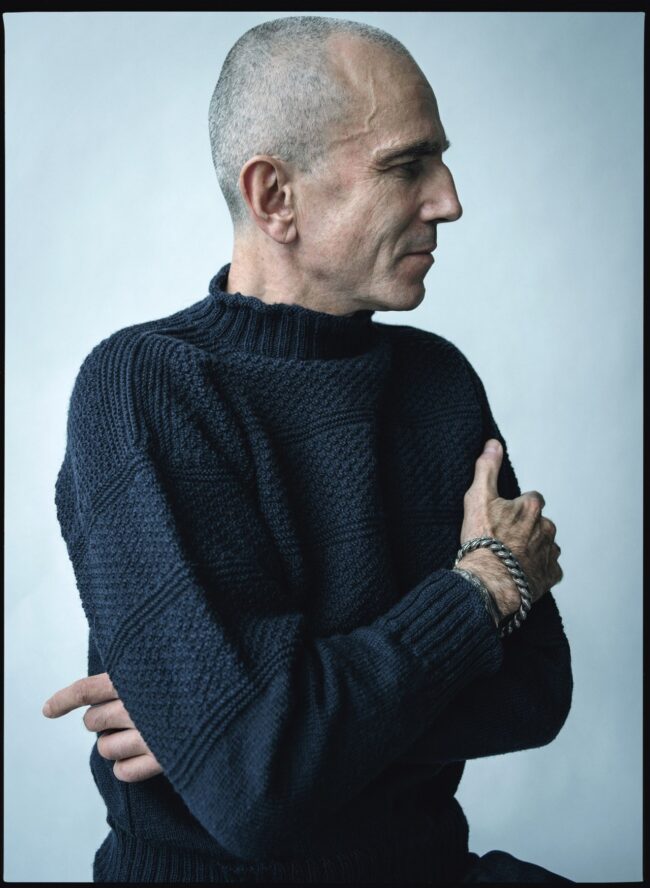

In the last few years, I’ve been doing a series called “Excited to Wear.” It’s my way of sidestepping the pointless exercise of defining menswear “essentials,” a concept that flattens the richness of style into generic shopping lists. Instead, I prefer to discuss clothes that excite me as the seasons shift. This spring, I’m drawn to clothes that reflect work and leisure—not as polar opposites but as parallel expressions of human wholeness. After all, spring and summer are the seasons for idleness, marked by bikes that creak out of garages and folding chairs that live in trunks. This list is about the clothes I like to wear for light work on warm afternoons and dawdling on cool evenings. It’s clothes for gardening, brunch, and listening to rediscovered LPs. Hopefully, you can find something here that inspires you for your wardrobe.

Keep reading