For the last few years, I’ve been doing these posts about things I’m excited to wear for the season. They’re a way for me to talk about things I’m excited about without getting into the fraught concept of “wardrobe essentials” (which feels increasingly less relevant nowadays when people have such different needs and lifestyles). Still, readers have found these posts to be useful as seasonal style guides. Here’s this year’s “excited for spring” post with a bonus soundtrack at the end. You can check previous years’ posts for 2018, 2019 (I also did one for summer), 2021, and 2022.

CHAMBRAY AND SILKY SHIRTS

I’ve always been primarily an oxford cloth button-down guy. I admire the style’s place in American clothing history, as well as its casual, rumpled nature and bookish appeal. However, in the last few years, I’ve also added two other shirt styles to my regular rotation: snap-button Western shirts, mostly those rendered in denim or needlecord, and silky shirts made from slippery materials such as rayon, Tencel, and actual silk.

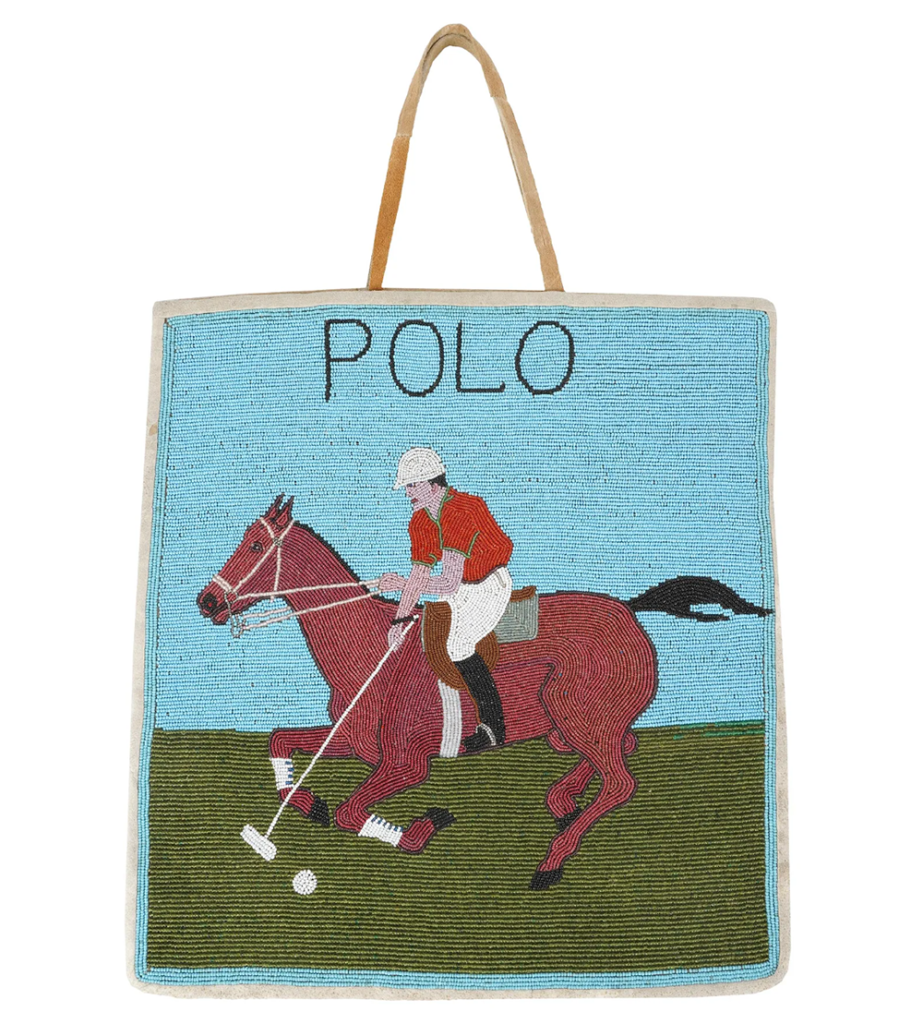

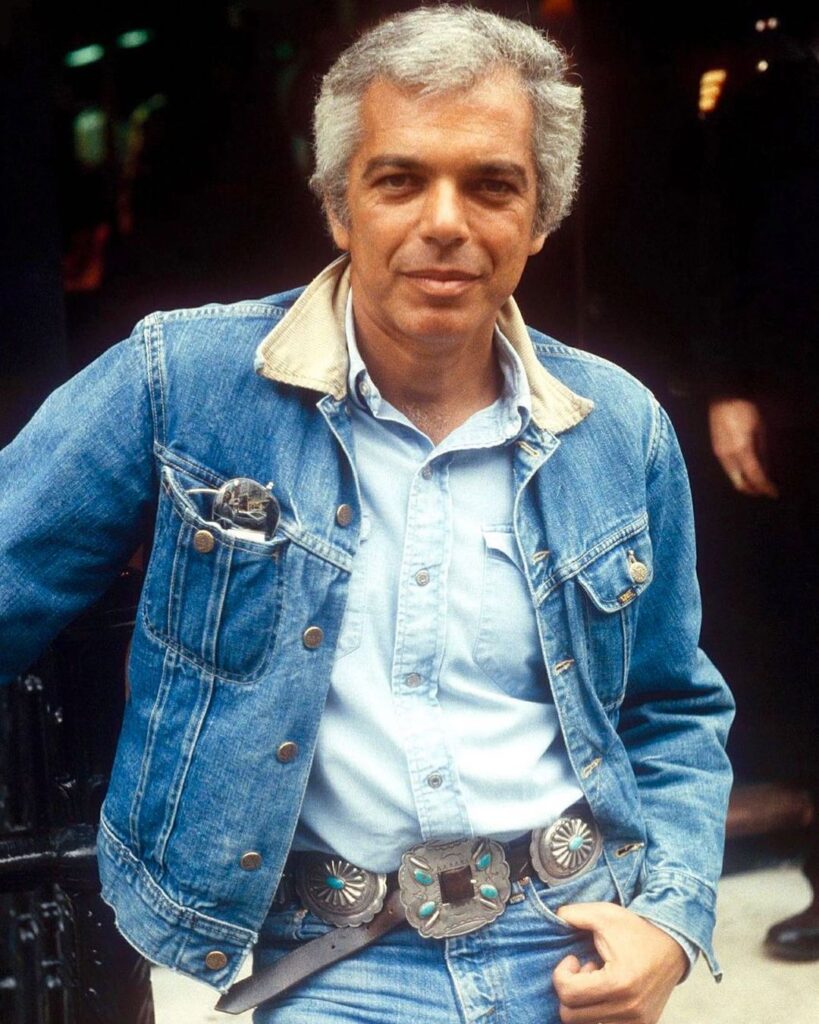

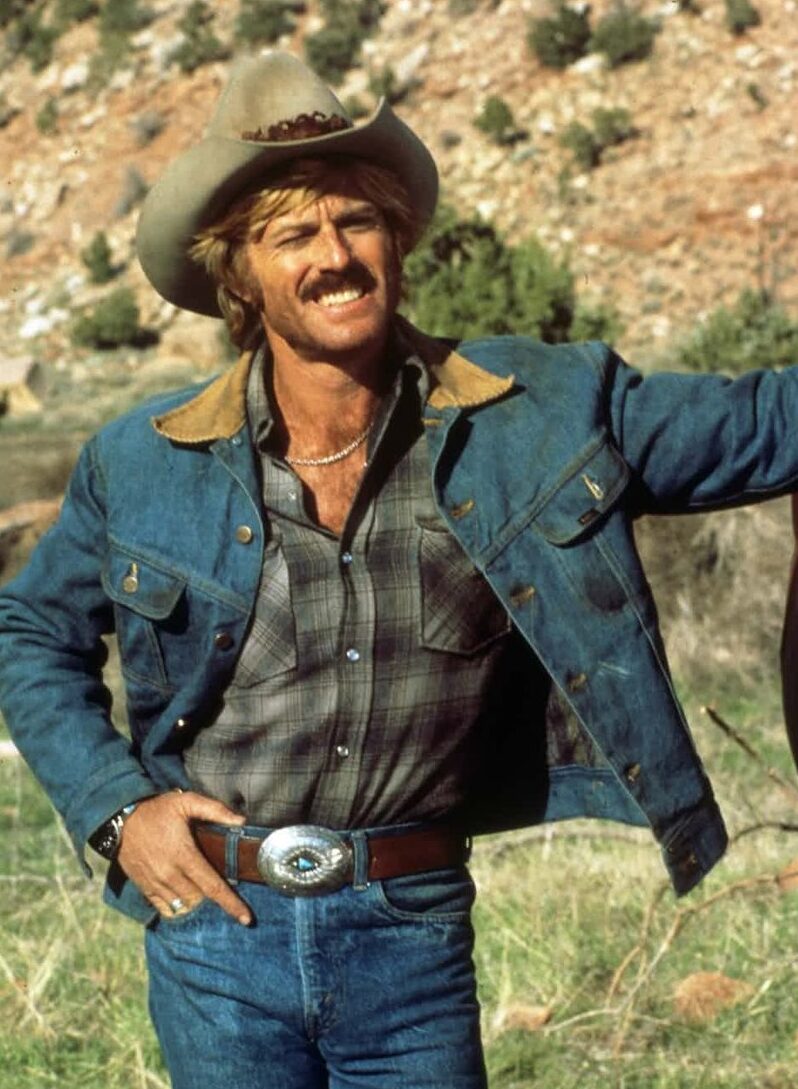

It’s interesting that the two most iconic American shirts involve horseplay. The first, of course, is the oxford cloth button-down, made at the turn of the 20th century when John E. Brooks of Brooks Brothers imported a collar style he saw on British polo players. Roughly fifty years later, Jack A. Weil of Rockmount Ranch Wear improved the denim work shirt closely associated with rodeo cowboys and ranch hands by replacing the buttons with metal snaps, making it America’s other button-down. I like snap-button denim Western shirts for how well they fit into workwear wardrobes, complementing anything from chore coats to bomber jackets to denim truckers in similar indigo colors. They also work surprisingly well under casual tailoring, adding a rugged American charm to things such as Scottish tweed sport coats and brushed cotton suits. They can, however, be a little suffocating this time of year. Denim is a tightly woven twill that can be heavy even in shirting weights. So I’ve returned to chambray.

Chambray, also known as cambric because it originated in the French town of Cambrai, is one of the simplest fabrics you can wear. It’s a pure cotton, plain weave made with a cross-hatching of colored yarns and a white fill. However, for such a simple fabric, it is rich in cultural significance. Much of men’s clothing history can be read not as a series of emerging designers or trends but rather as surface-level manifestations of social identities, cultural clashes, and even political fights. In the early 20th century, class warfare was coded as a battle of shirt collars. Manual laborers stretching from the steel mills of Pennsylvania to the shipyards of California’s coastline wore light blue chambray shirts because they were cheap and hid dirt easily. Pencil pushers, on the other hand, wore white poplins and broadcloths while quietly working inside well-mannered offices. Through the 20th century, these metonymic models—the blue-collar and white-collar worker—rose together, allowing writers to sidestep the uncomfortable discussion of class. Today, even though laborers wear shirts of all colors, the term “blue collar” persists as a way to describe people who earn a living through their sweat.

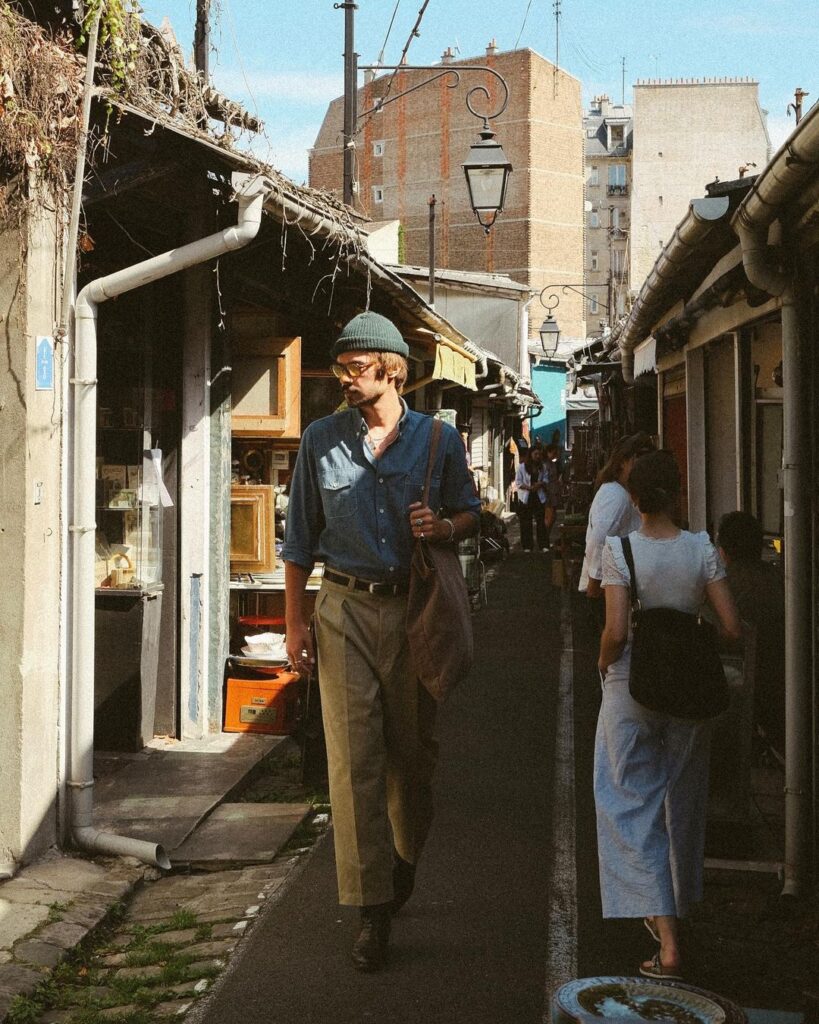

Like denim, chambray adds something rugged to an outfit. In the summertime, however, it performs better than its tightly woven twill counterpart because it can be made in lighter weights and more breathable weaves. I wear chambray shirts with patched-up RRL chinos and a Lee 101-J trucker jacket. If you get one made from a dressier version of chambray, such as those from G. Inglese or the online made-to-measure shirtmaker Proper Cloth, you can even pair it with casual tailoring. When the weather gets scorching hot this summer, wear a chambray shirt open over a white t-shirt, layering it like a shirt jacket. Doing so allows you to add visual interest to a plain outfit without suffering through the weight of actual outerwear. Just look for casualizing details: two chest pockets, cat eye buttons, and double-needle seams to give the shirt character.

I’m also excited to return to slippery materials, such as rayon, Tencel, and silk. In the early 20th century, rayon was held as a modern marvel. It was marketed as a silk alternative, giving people the soft, slippery comfort of silk but with better breathability. Rayon performs so much better than silk that even the most traditional tailors, including those on Savile Row, switched to rayon linings generations ago. However, rayon and its cousin Tencel have one downside when used for shirts. Most manufacturers recommend washing these fabrics by hand, not putting them through a machine laundering process—a rule I’ve never strayed from. That can be a hassle for a summer shirt, but I’ve discovered that I can get two or three wearings before needing to clean them (unlike cotton, which holds sweat and odors easily). My favorite thing about these shirts is how they make me feel like Richard Gere in that famous American Gigolo dressing scene, despite not looking anything like him.

Rayon and Tencel were my gateway drugs into silk, which I previously avoided due to cost. But when my friend Peter Zottolo commissioned a custom, 1970s-style matte silk shirt from Post Romantic, I became intrigued. Post Romantic (now an advertiser on this site) works with a series of tailoring workshops in Pakistan’s Punjab region. Compared to workshops in Italy or England, the relatively low cost of labor is how they can sell things such as fully custom-made shirts for as little as $55. I like their bohemian style, so I sent them a photo of a Umit Benan satin-silk shirt last year. The Umit Benan shirt is beautifully styled—a boxy fit made with a camp collar, like something Yves Saint Laurent may have worn during his trips to Marrakech. But whereas the Umit Benan shirt was $1,260—several rungs above my tax bracket—my Post Romantic version only cost me $115. I was impressed by how well Post Romantic copied the look, even without an in-person fitting. I plan to wear it this summer with drawstring trousers and huaraches, casual tailoring, and a pair of tan RRL jeans with a Western belt and cowboy boots.

Options: Byrceland’s, Drake’s, Post Romantic, Wythe, Portuguese Flannel, Blue Blue Japan, Eastman, The Real McCoys, Ralph Lauren, Spier & Mackay, Sid Mashburn, Imogene + Willie, 3sixteen, Gitman Vintage, RRL, Carhartt WIP, Ginew, Knickerbocker, Factor’s, Second Layer, Wacko Maria, The Letters, Needles, Orslow, Engineereed Garments, Self Edge, Sun Surf, Todd Snyder (tons of options for chambray, rayon, and Tencel), and J. Crew for affordable chambray and cotton-viscose prints (this Japanese selvedge chambray is a tremendous value at $50 with the code SHOPSALE)

ALL BLUES COMPANY’S DEEP PILE FLEECE

The menswear market has shifted in two directions over the last two decades. On the low end, there’s fast fashion, where you can buy shiny, ill-conceived clothes hastily cobbled together from an algorithmic run of trends for mere pennies. Then there’s designer clothing, which is exquisitely made but is sold at cosmically expanding prices. The market can be discouraging for anyone just starting to build a better wardrobe. All Blues Company is a welcome respite in this regard. Browsing this Leeds-based boutique is like being able to shop through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. During the early 2000s, stores such as Hickoree’s and Unionmade introduced nostalgic men to long-forgotten American labels that provided long-term value. Since then, many American-made brands and factories have closed, customers have become more savvy, and a lack of brand loyalty has commodified everything. Nonetheless, All Blues Company occupies that dwindling section of menswear where mid-priced but well-made clothes can still be found: Scottish Shetland knits for $135, French wool chore coats for $185, and tweed raglan overcoats for $235.

I was elated when they introduced these deep-pile fleeces earlier this year. Modeled after a version of Patagonia’s Retro-X that debuted in the early 2000s, these jackets feature a much deeper pile than modern fleeces. In recent years, the deeper pile has gained cultural capital as the cleaner, more behaved short-pile fleece—particularly in vest form—has become ubiquitous in cubicle offices, often associated with financiers and tech workers. Unfortunately, because these jackets are in high demand among vintage collectors, the fluff can cost a fortune. Prices for mint condition jackets on eBay can reach $1,250 (dingy versions can be had for about half the price). Even Japanese reproductions aren’t much cheaper. All Blues Company’s fleece, on the other hand, is currently on sale for $237 (15% off with the code SPRING15).

This jacket performs admirably during the shoulder season. The fluffy fleece is water-resistant and windproof, while the mesh lining is breathable and draws moisture away from the skin. It’s ideal for days with an indeterminant chance of light rain and when temperatures can unpredictably swing from briskly cold to uncomfortably warm. It’s easy to understand why hikers in the Pacific Northwest wear this style. My only complaint is that the side pockets zip downward to close when I’m used to pulling them in the other direction. However, it’s a minor quibble for a jacket that pairs so well with olive fatigues or blue jeans, grey sweats, and all-black Blundstone boots. Plus, it makes me look like Snuggle the fabric softener bear or a sexy cauliflower.

Options: All Blues Company, Kapital, Drake’s, Blurhms, Snow Peak, North Face, Camiel Fortgens, and Manastash. Although not technically a fleece, Drake’s Casentino pullovers are a distant cousin and look great in similar outfits.

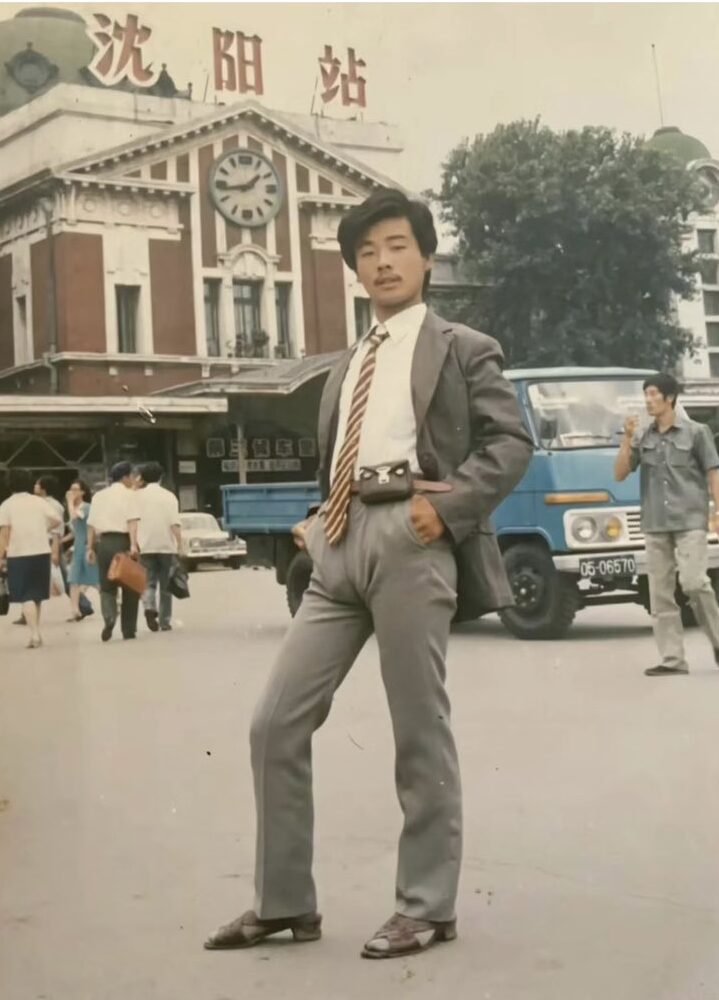

KAPTAIN SUNSHINE PHOTOGRAPHER JACKET

In the 1970s, China and the US slowly waltzed their way to normalizing relations. The decade opened with a ping-pong match between the two countries, coining the term ping-pong diplomacy. This paved the way for diplomatic overtures, Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, and members of Carter’s administration visiting a few years later. By the decade’s end, Deng visited the White House to sign historic new accords with President Carter. The new era of Sino-US relations was perfectly captured with a photo of Deng visiting a rodeo show in Texas, smiling from beneath his ten-gallon Stetson hat while wearing his communist garb.

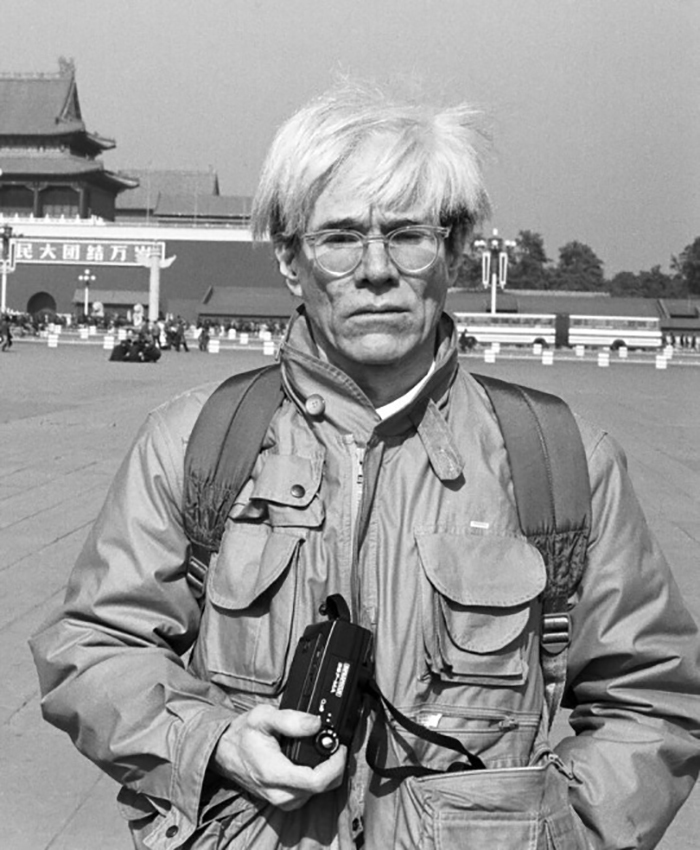

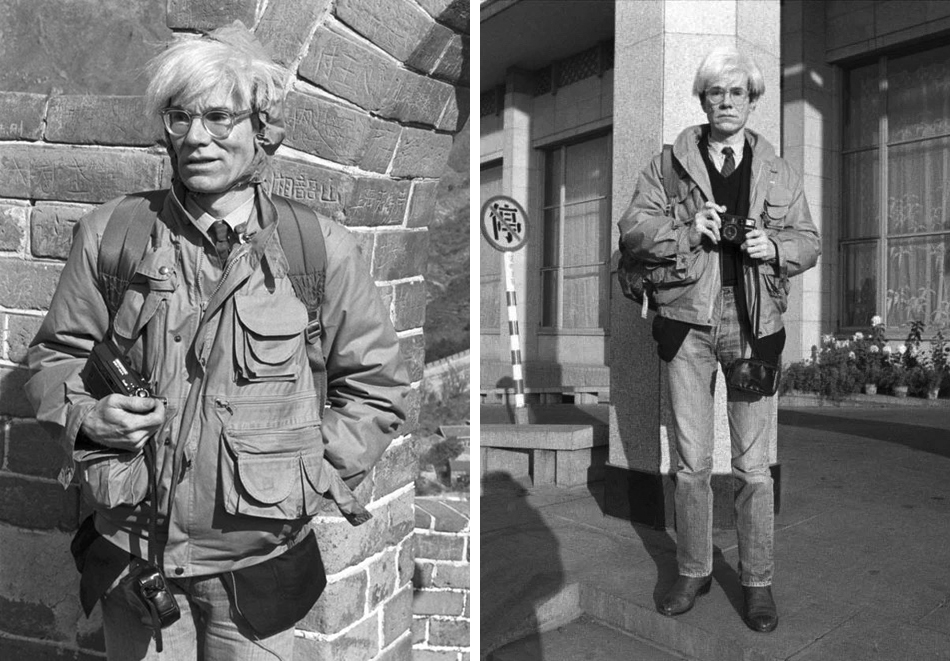

The signing of those accords meant that Americans could now freely visit China, and among the many Americans in that first wave of tourism was Andy Warhol, who visited in 1982 at the behest of Alfred Siu, a young industrialist fascinated by the West. Siu was opening a new disco in Hong Kong and wanted portraits of the newlywed Prince Charles and Princess Diana for his club. At first, Warhol traveled to Hong Kong with a group of his friends, including his flamboyant Texan manager Fred Hughes. But shortly after the two sides finished business, Siu surprised them with an impromptu invitation to visit China’s capital. Warhol and his friends eagerly took the offer.

While in Beijing, Warhol photographed everything that piqued his interest, from the sweeping vistas from atop the Great Wall to the courtyard neighborhoods surrounded by narrow streets known as hutongs to the portrait of Mao at Tiananmen Square, which he famously reinterpreted into iconic pop art (whether in earnest or politeness, Warhol said he thought the original Mao portrait was better than his interpretation). He also photographed the Chinese people, whose daily uniform—something resembling a Chinese chore coat paired with matching work trousers—impressed the American painter. “I like this better than our culture. It’s simpler,” he said. “I love all the blue clothes. Everyone wearing blue. I like to wear the same thing every day. If I were a dress designer, I’d design one dress over and over.”

While in China, Warhol did wear the same outfit every day. His daily uniform involved a soft-shouldered navy sport coat paired with a button-down shirt, striped necktie, v-neck sweater, some blue jeans, and a pair of beat-up cowboy boots. Since he relied so much on his camera, he also wore a jacket with plenty of pockets. There were pockets for his copy of Mao’s Little Red Book, his countless rattling film canisters, and, of course, his camera. There were pockets within pockets, and hidden inside those pockets, even more pockets. The jacket was made in the late 1960s by a Parisian designer named Maurice Renoma, who dubbed it Multipoche—French for “multiple pockets.”

The original Multipoche is difficult to find nowadays (I’ve only seen it on Japanese auction sites). However, Kaptain Sunshine has a reasonably faithful reproduction. I purchased one several years ago, and it has become one of my favorite warm-weather jackets. Named after Andy Warhol’s trip to China, Kaptain Sunshine’s Photographer Jacket features the same multi-pocket design, zippered front, and stand-up collar as the original. I like it for the same reasons I like Engineered Garments: the jacket is a little goofy, but in the best way possible, and it goes well with things I already wear on a regular basis, such as raw denim jeans, olive fatigues, plaid work shirts, textured knits, grey sweatshirts, and chunky boots.

Kaptain Sunshine’s Photographer Jacket returns this season, albeit with some minor changes. The large pocket at the back has been removed, which I think makes it more appealing. The hem is less elasticated, giving the silhouette a cleaner appearance. It also comes in tan or blue (I think both colors are equally appealing). The best thing about the jacket, naturally, is the number of pockets, which not only add visual interest to simple summer outfits but also serve a practical function. In these teeny tiny pockets, you can carry three sour jellybeans, a small, folded piece of paper with the perfect soul-shattering comeback, and your smug sense of superiority for having a jacket modeled after something Andy Warhol once wore in China.

Options: No Man Walks Alone, Namu Shop, and Signet

RIBBED COTTON TANK TOPS

A few months ago, I was shopping for house supplies at Target when I came across a bin full of Hanes undergarments. Inside were Hanes’ ribbed cotton tanks—three-pack for just $10. I had long been interested in ribbed tanks after seeing them worn stylishly with 1970s-styled outfits and Wrangler Wranchers. So I picked up a pack.

Ribbed cotton tanks are more commonly known as “wifebeaters,” an ugly nickname that stuck to this style sometime in the mid-20th century. No one is quite clear how, but there are two origin stories. One says that the name started in 1947 when a newspaper printed a story about James Hartford Jr., a Detroit man who was arrested for brutally beating his wife to death. When the story came out, the nation gasped at the photo of Hartford in his sleeveless undershirt, stained from dribbles of baked bean sauce, with a caption under the picture that read, “the wife-beater.” The other theory suggests it started with the 1951 film A Streetcar Named Desire. In one scene, Marlon Brando, similarly clad in a sleeveless undershirt, shoves Vivien Leigh to the ground, raging and shouting at her while throwing bits of her outfit around.

If the ribbed tank has lost any of its association with violence, it has only traded it for other stereotypes about working-class men. The style is also known as the “guinea tee” and “dago tee,” ethnic slurs for the working-class Italian immigrants who were known to wear this style in the mid-century (back when Italians were not yet considered “white”). By the 1990s, ribbed tanks became associated with hip-hop culture, Chicano culture, and gang violence. The most neutral term for this sleeveless undershirt is “A-shirt,” short for “athletic shirt,” but that has never stuck. In the wake of the #MeToo movement, Moises Velasquez-Manoff wrote an op-ed for The New York Times, asking: “Are We Really Still Calling This Shirt a ‘Wife Beater’?”

View this post on Instagram

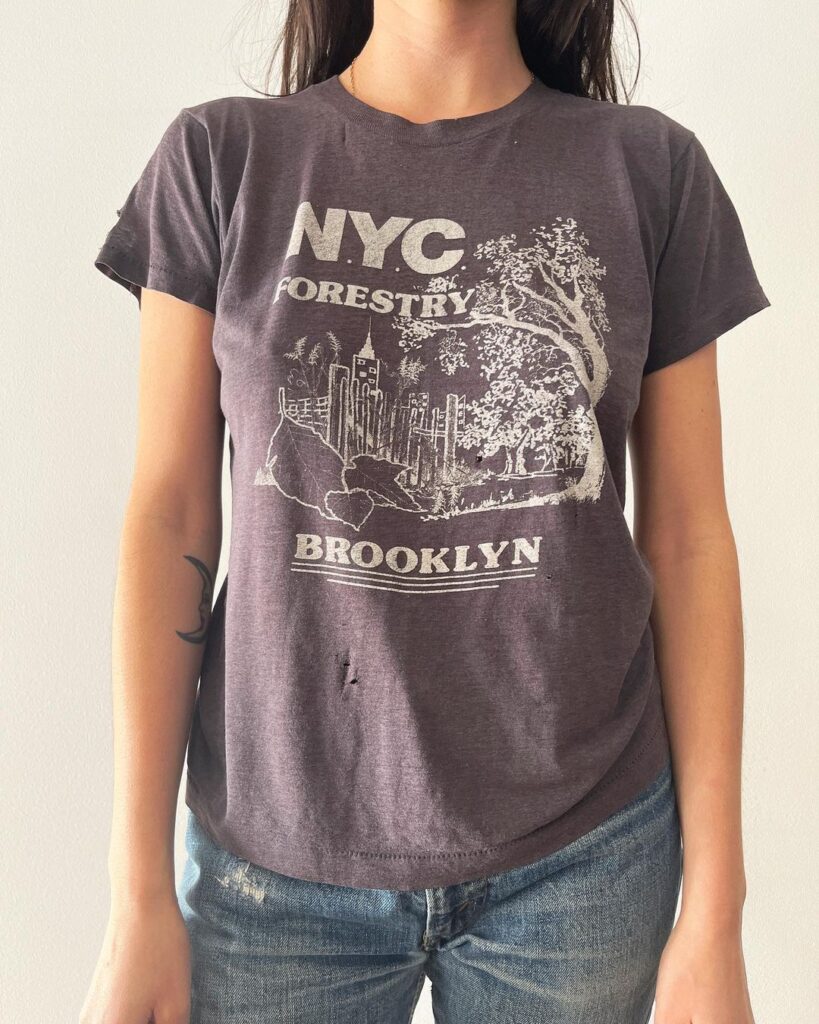

There’s no reason why we still have to call these wifebeaters. The term A-shirt is awkward, but “sleeveless undershirt” or “ribbed tank” will do, even though not all sleeveless undershirts are technically ribbed. Despite some of the negative associations, the ribbed tank persists mainly because it’s cheap and functional, helping to sop up sweat before it soaks into the wearer’s outermost shirt. Velasquez-Manoff points out in his op-ed that the style also taps into “imagined working-class male virility.” Their sociological shadings make them a good accompaniment with workwear—better under chambray, denim, and flannel shirts rather than oxford cloth button-downs associated with prep and Ivy.

I like them because they achieve two undeniable facts about men’s style. First, every outfit looks better with a bit of layering. This is why fall/winter outfits are always better than their spring/summer counterparts. The ability to combine overcoats with shirts, sweaters, and scarves allows you to build more interesting ensembles. In the summertime, however, men molt these layers and are left with plain button-ups that do little more than reveal the shape of their bodies. The sleeveless undershirt allows you to add a bit of layering without introducing much heat retention.

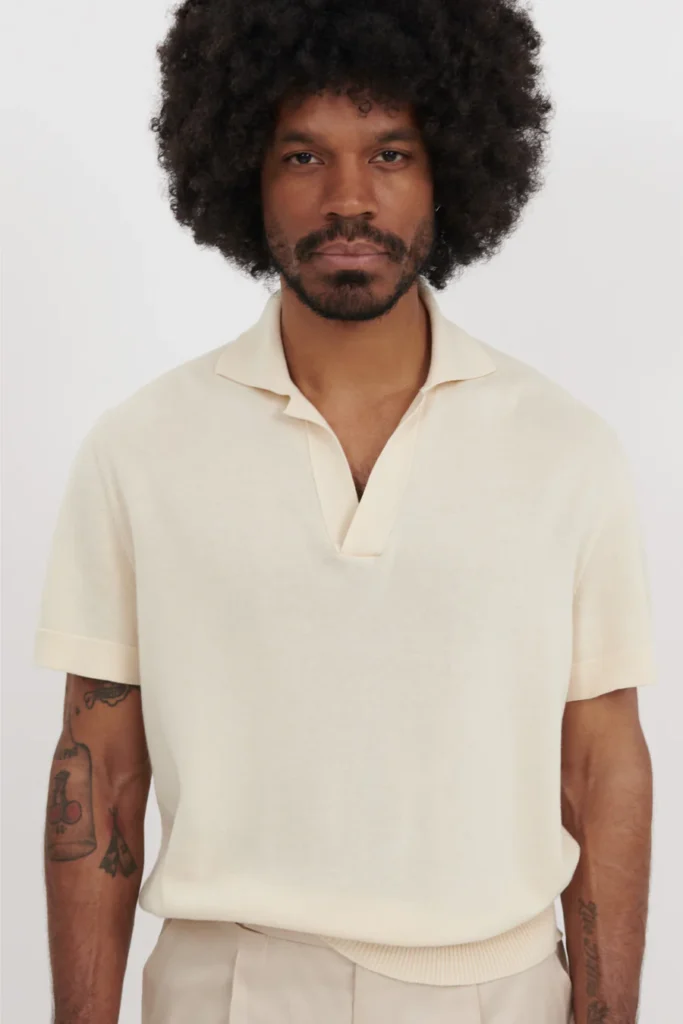

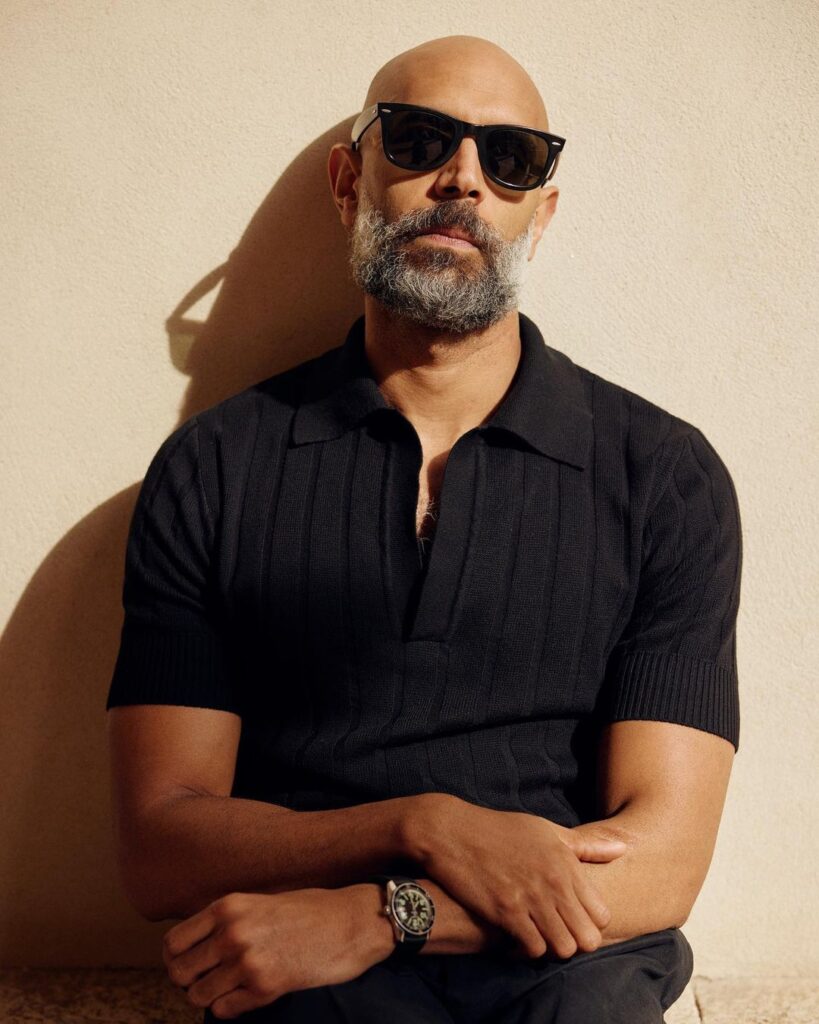

Secondly, casual outfits often look better with the first two or three buttons unfastened, but most men don’t have the build necessary to pull that off. The undershirt allows you to hide a bit of softness while creating a flattering v-shaped neckline that the front edge of a suit jacket would confer. If you happen to have an athletic build, you can wear almost any shirt—a chambray work shirt, an Aloha shirt, or the knitted lace shirts that have been popular recently—open and over a ribbed tank. Otherwise, I recommend buttoning up the shirt halfway up the torso if you’re soft bodied, like me.

I know ribbed cotton tanks can sound intimidating, especially if you mostly favor the conservative styles that dominate classic menswear blogs. But they’re a cheap experiment at 3 for $10. For some outfit inspiration, browse the Instagram accounts JoeKenneth, AndreTheApple, EdgyAlbert, Marco.Pants, Satie_San, Casatlantic, and MaskSantaFe. Scott Fraser Simpson also works them well into his lookbooks, showing how you can work them into “retro cool” outfits. The easiest outfit, I think, is to team them with a denim Western shirt, black pair of Wrangler Wranchers, and some black side zip boots. Accent with some jewelry, if you can.

Options: Hanes (size up), Uniqlo, Calvin Klein, Wythe, Scott Fraser Simpson, Aime Leon Dore, Todd Snyder (also available in mesh), The Letters, Mack Weldon, Lemaire, CDLP, Sunspel, Corridor, Velva Sheen, and Industry of All Nations

CUBAN LINK NECKLACE

I’m a sucker for a good American story: the oxford cloth button-down and penny loafer as the sine qua non of the post-war Ivy look, the snap button Western shirt and cowboy boot as symbols of America’s mythologized past, and how blue jeans went from Gold Rush garb to Silicon Valley vêtement within 150 years. Similarly, no accessory better reflects the sparkling spirit of Americana than Cuban link chains, a story forged by Latin immigrants, Black hip-hop artists, and American street culture.

Cuban jewelry came to the US with the arrival of Cuban exiles. In 1959, shortly after Castro overthrew the Batista’s regime and established a new government, millions of Cubans from diverse social positions fled to the US, first by boat and later by plane. Many of these émigrés worked as jewelers in their home country. And so, naturally, they made a life in the United States—many of them while based in Florida and especially Miami—crafting and selling gold jewelry.

Cuban chains are distinguished by the tightness of their links. They’re made by twisting gold wires into a coil, which is then cut and linked into a simple chain. This chain is then wrenched flat and filed into its final form. It’s a beautiful process, but since clothing is just as much about semiotics as it is about craft, it took Black hip hop artists and street culture to give this style cultural meaning. When I was shopping for a gold necklace last year, I knew it had to be a Cuban link because of this album and film.

If you’re in the market for gold jewelry, I have some recommendations. First, consider the resale value. Along with certain mechanical watches, gold jewelry is unique in that you can recoup the majority of your investment. However, this is easier to do with solid gold items rather than gold-plated or gold vermeil. When estimating how much you may be able to recoup later, calculate the item’s gold weight (this will require a scale and some basic arithmetic). Then multiply that weight by the gold market price and compare the result to the seller’s asking price for the item. This will give you an idea of how much you’re paying for the item’s precious metal, the labor markup, and how much you might be able to recoup later if you decide to resell.

Second, unlike other writers, I don’t believe there’s anything inherently wrong with purchasing gold-plated or gold vermeil jewelry. The gold surface will eventually wear away, exposing the less expensive metal beneath. This means you will eventually need to pay for the item to be re-plated, which can be costly. Depending on the mixture of metals, you may also see some tarnishing—the silver’s blackening coming to the surface, or the copper turning green, which sometimes rubs off on your skin. It’s rarely worth polishing these items since you can just further wear away the gold surface. But for all the downsides, gold-plated and gold vermeil can be a good way to test whether you like wearing gold-colored jewelry at all. The cheapest gold-plated necklaces generally start around $50—less than 1/10th what you’d pay for the same item in 14k solid gold. It’s all about knowing what you’re getting into.

Finally, if you’re looking for a Cuban link chain, I recommend going straight to the source. Miami Cuban links, like champagne from France’s Champagne region and Donegal tweed from Ireland’s Donegal county, should have some connection to the Cuban community in Miami. Buying directly from the people who make these in the Sunshine State not only gives you better provenance but also allows you to sidestep the markups imposed by retailers such as Trax NYC. Plus, many jewelry retailers nowadays import their Cuban link chains from Italy—where they are commonly made by machine—rather than the Cuban artisans who produce these by hand. For an everyday necklace that you can wear with Western denim shirts, rayon camp collar shirts, and plaid flannels, I like 14k Cuban link necklaces that are 7mm wide and 22″ long.

For something more subtle, consider 3mm diamond-cut ropes or Francos. These are the sorts of things you can wear with everything from prep to streetwear to Westernwear. Even Cary Grant in North by Northwest, the prototypical classic menswear film, wore a thin gold necklace under his suit (if you decide to wear a gold necklace with tailoring, I recommend doing it with something such as Husband’s 1970s styled suits, rather than the trady outfits found at Brooks Brothers, and sticking with the thinner 3mm gold chains that won’t overpower your outfit). Gold necklaces are especially good in the spring/summer months, as they add a metaphorical and literal sparkle to simpler ensembles, such as camp collar shirts paired with shorts.

Options: For Cuban links, check out Daniel’s Jewelry, CRM Jewelers, Gold Fever Miami, Rey’s Gold, Las Villas Jewelry, Gus Villa Jewelry, and Limaxi. I bought mine from Garcia’s Jewelry, a shop in Hialeah with an in-house workshop at the historic Seybold Building in Miami. When I was shopping around, I found they had the best online prices.

MARGIELA LEATHER SLIPPERS

My favorite summer shoes are huaraches, but when I couldn’t find mine earlier this season, I rummaged through the back of my closet and pulled out a long-forgotten pair of Margiela leather slippers (sold as babouches, although they don’t really resemble that Morracan style). I bought them a few years ago after seeing a photo of my friend Kyle wearing a white pair with a blue seersucker suit at his birthday party. “They’re from Margiela,” he told me, “but you might be disappointed with the construction quality.” He was right. Shortly after buying a pair, mine languished in the darkest corners of my closet. The rubber sole felt cheap—reminiscent of the ever-expanding foam UPS uses to cushion packages—so I never wore them.

But recently, I found a new appreciation for the sole’s lightness and the leather lining’s buttermilk texture. Margiela’s slippers are surprisingly comfy, even if obviously overpriced (as is common with designer footwear). Unfortunately, the current Creative Director, John Galliano, turned the company’s famous Tabi toe into a luxury signifier—which seems to counter Margiela’s original spirit. So you can no longer get this model.

There are, however, good alternatives. No Man Walks Alone, an advertiser on this site, is carrying leather slippers this season from the French maker La Botte Gardiane (named after the cowboys in Camargue, in the South of France, where the company has a small, charming workshop). I also like the woven leather slippers from Nisolo, Albert-styled shoes from Manolo Blahnik, and, if your wardrobe is contemporary enough, the oddly seamed, monastic slippers from Lemaire that look like something a Belgian artist would wear. Sabah has some intriguing slippers that look fairly similar to the shoes I bought from Margiela (only theirs lack a heel). I find that soft, unisex style adds a bohemian sensibility to workwear ensembles, helping to soften the style’s hard edges (they go easily with chore coats). You can also wear them with camp collar shirts paired with loose, drawstring pants or summer shorts. Browse Stoffa’s Instagram for endless inspiration.

Options: Le Botte Gardiane, Nisolo, Mulo, Manolo Blahnik, Lemaire, Sabah, Bode, Wales Bonner, The Row, Rainmaker Kyoto, Bryceland’s, and LB Evans

TONAL SEERSUCKER SUIT

When I was in graduate school, the smartest and most accomplished person in my entering class wasn’t someone who toiled away every waking hour but a woman who refused to work on Saturdays. Saturday was her day off, regardless of how many deadlines she had looming over her head, how many emails needed answering, or what pressing exams were around the corner. It took me years to realize the wisdom of her philosophy. Taking at least one day off a week—remarkably difficult when many people don’t work traditional 9-5s—gives you something to look forward to and helps avoid burnout. Plus, for the clothes mad among us, it offers an opportunity to dress up.

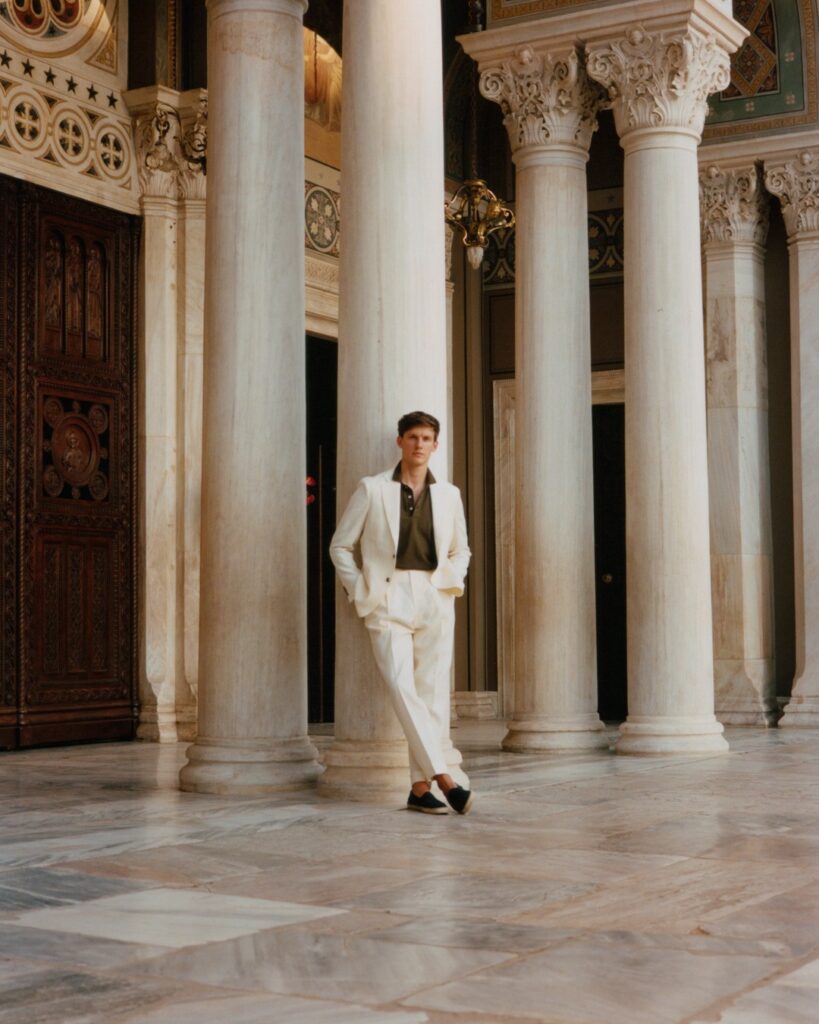

Like most men, I rarely wear a traditional dark suit nowadays. “Serious suits” are reserved for weddings, funerals, and court appearances. Instead, I mostly wear what I call “Happy Suits”—suits you wear for a mood. Happy Suits require intentionality, as they’re too casual for environments that call for a suit and too formal for instances that don’t. I find that the best time for them is on your days off. Suits rendered in cotton, linen, or mohair blends, or worsted wools in colors such as chocolate brown rather than corporate navy, are good for going to a museum, seeing a show, or having dinner at a nice restaurant. The restaurant doesn’t even have to be particularly upscale. I wear Happy Suits to eat $30 plates and consume $15 drinks. My philosophy is: if I’m paying $30 for spaghetti, I’m damn sure not going to wear what I wore on the couch.

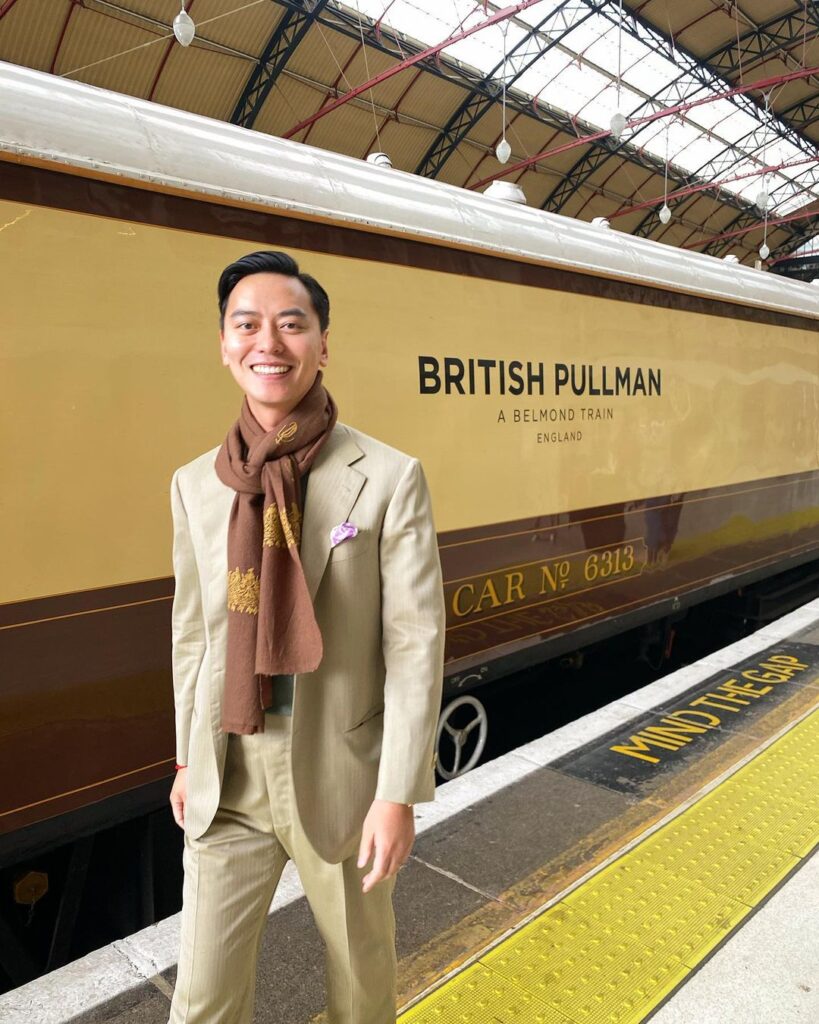

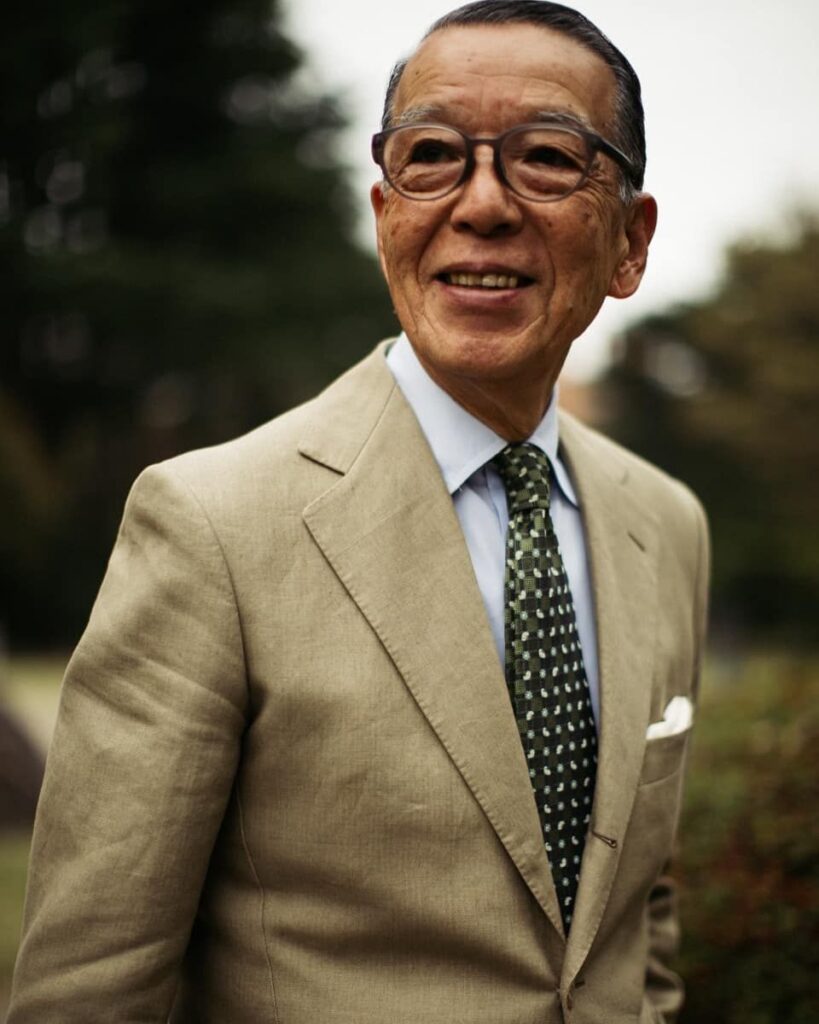

Most of my suits nowadays are Happy Suits, but the one I’m most excited to wear this season is a tonal navy seersucker I bought a few years ago from The Armoury. Seersucker derives its name from shîr and shakar, Persian for milk and sugar. The original color combination has always felt too preppy for me (although it looks fantastic on Alan See above). So I was happy to try out the more modern tonal variety. The Armoury’s version is made from a wool-silk blend, which drapes better than cotton. I’ve found that a tonal navy seersucker suit is perfect for Sunday brunches and day trips to the museum. Wool-mohair feels more elegant to me for evening affairs, although tonal navy seersucker works if the environment isn’t too formal.

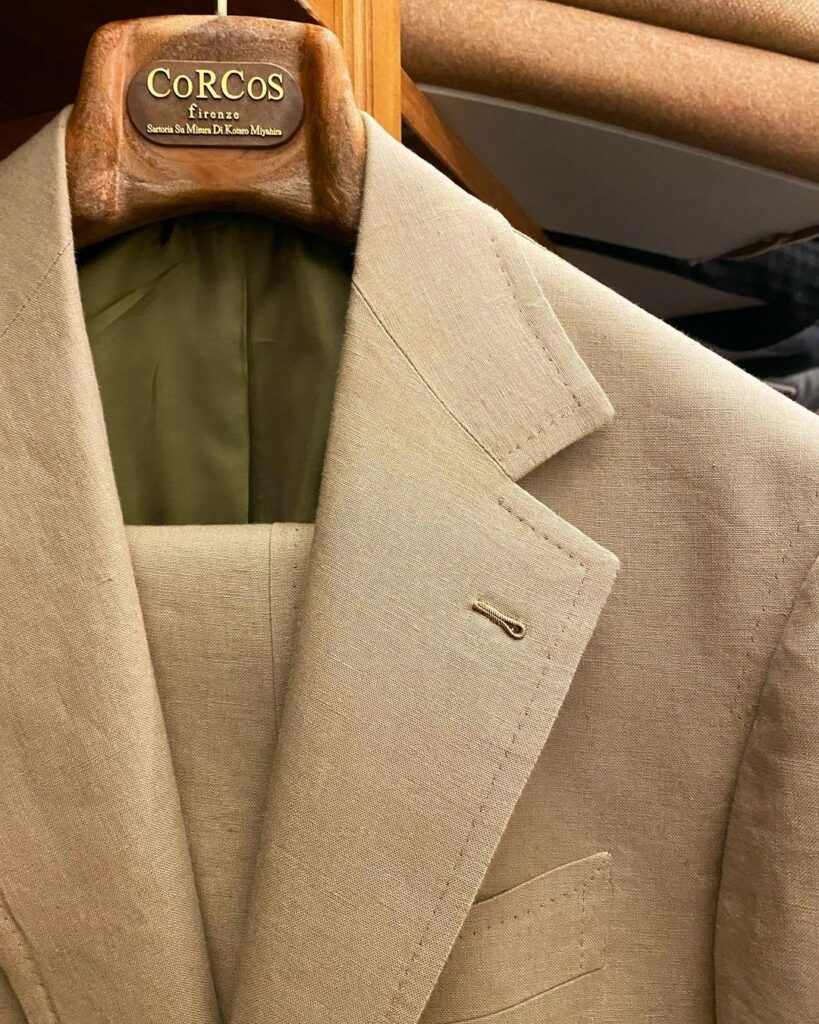

Options: There are lots of Happy Suits from various retailers this season. Some of the best I’ve seen include this midnight navy wool-mohair suit from The Armoury; olive glen check worsted, tobacco linen, and sage wool-silk-linen blend from Spier & Mackay; blue linen and seersucker from The Andover Shop; tan and olive poplin from J. Press; tonal navy seersucker from Orazio Luciano; tonal navy seersucker, brown linen, and tan wool-silk-linen from Cavour; brushed cotton at Natalino; taupe cotton-silk from Anglo Italian; and navy seersucker and teal cotton from Sid Mashburn. If you’re using a custom tailor, I recommend checking out the linens from W. Bill and Mersolair, navy seersucker in Loro Piana’s Mare, tropical wools from Draper’s, Harrison’s Spring Ram, and Fox, and gabardines from Huddersfield Fine Worsteds.

SPRING SPORT COATS

I can’t say I’m excited to wear a navy sport coat—navy sport coats are a staple in my wardrobe, and saying I’m excited to wear one would be like saying I’m excited to wear socks. But I can’t imagine getting through this summer without my Mock Leno jacket. Mock Leno is a distinctive, three-dimensional open weave with a lot of texture. It’s distinct from other tropical wools, such as Minnis Fresco, in that it’s much more obviously made for sport coats (whereas Fresco can look a bit suit-y). This is the sort of grab-and-go jacket you can wear with anything: grey tropical wool trousers, tan chinos, blue jeans, etc. For men who wear tailored clothing, I think it’s about as close as you can get to a wardrobe essential.

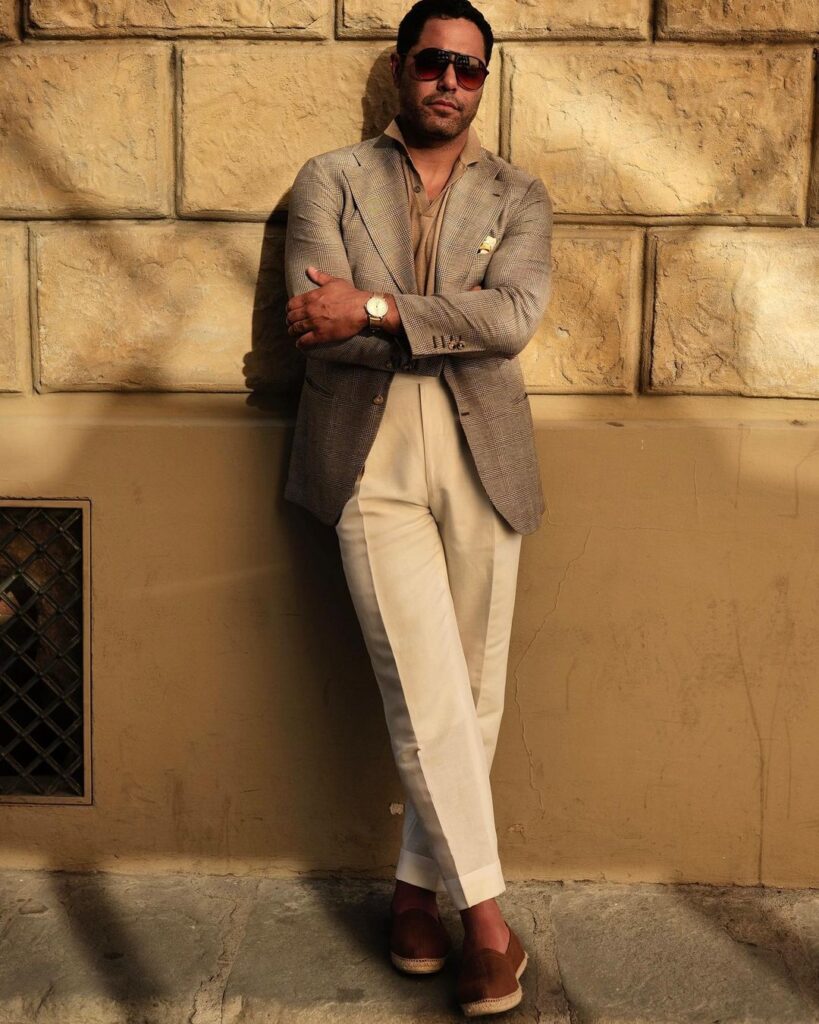

I am, however, excited to wear sport coats made from more distinctively warm-weather materials. Summer tailoring guides are full of suggestions for crisp linens, cottons, and tropical wools. But I’ve found that I get much more use out of my sport coats made from wool-silk-linen, which have advantages from all three fibers—the drape of wool, the sheen of silk, and the dry hand of linen. Wool-silk-linen sport coats have a unique texture, making them something like summer’s counterpart to winter’s tweeds. I also get a lot of use out of cream-colored sport coats with subtle patterns. In the right hue, they work equally well with trousers in mid-gray, taupe, and brown.

A few years ago, George Wang of BRIO mentioned to me that he thinks bright colors such as faint lemon yellow and pink work better than earth tones when the weather gets very hot. The comment stuck with me, and I’ve since noticed how much I admire jackets in light blue, pale salmon, and sandy beige with a warm tinge. If you’re worried about trouser pairings, remember that stone-colored trousers work with pretty much anything. Raw silk also works especially well this time of year—if you can find it. Besnard, an advertiser on this site, has some particularly tasteful ones with subtle slubs. This navy raw silk sport coat can be paired with anything, but I think the off-white version would be particularly elegant with brown trousers, a white shirt, and some black tassel loafers.

Options: Mock Leno at Natalino; raw silk at Besnard; cream cross-ply, tan linen check, and seafoam green at The Armoury; green checked seersucker from Doppiaa; French linen in cream check and solid olive from Orazio Luciano; pink herringbone, cream linen, and navy hopsack from Spier & Mackay; pink wool-linen from The Andover Shop; madras and tan gun club from J. Press; yellow wool-silk-linen, brown glen check, and brown wool-silk-linen from Cavour; and navy ghost blazer and brown houndstooth from Sid Mashburn. If you’re using a custom tailor, check out the wool-silk-linen mixtures from Huddersfield Fine Worsted, Caccioppoli, and Harrisons; Harrisons Indigo (basically wool-silk-linen without the sheen of silk); wool-hemp from Carnet; everything from Anglo Italian (Italian summer fabrics made with English taste); and Maison Hellard (French linens with very tasteful designs)