Menlo Park, a suburb located outside of San Francisco, is known for being the venture capital engine for California’s tech economy. The city today is a portrait of serenity, with its multi-million dollar homes, well-manicured lawns, and wide, tree-lined streets. In 1969, however, when Victor Cizanckas was appointed as the city’s new police chief, Menlo Park and the rest of the Bay Area were in turmoil. The decade’s protest movements were met with increasing state violence, sometimes verging on open warfare. As images of attacking police dogs and civil rights abuses flickered across television screens, Black leaders in the neighboring Belle Haven and East Palo Alto communities organized marches to demand equal treatment. At UC Berkeley, Mario Savio stood at steps of the university’s admissions building, Sproul Hall, where he famously urged students to put their “bodies upon the gears” in defense of free speech. That night, police officers moved in and arrested nearly 800 demonstrators, making it the largest mass arrest in California’s history. And just two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., with riots raging across the United States, the Oakland police engaged in a shootout with the Black Panther Party, killing young Bobby Hutton.

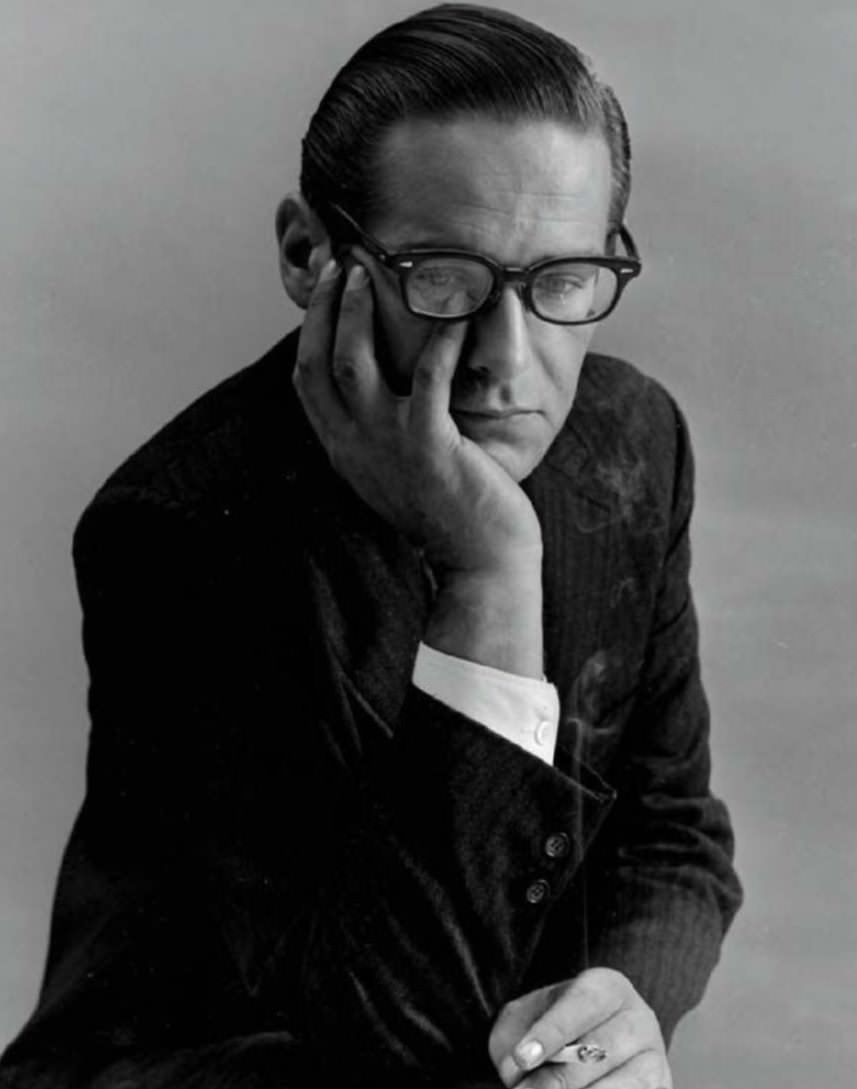

It’s no wonder so many Americans that decade had such little faith in policing, including residents of Menlo Park. To help rebuild that trust, the newly appointed police chief, Cizanckas, then 39 years old, decided it was time for the most superficial reform — he’d change the department’s uniform. For years, Menlo Park’s officers wore the same, neatly pressed, dark blue attire that commanded military authority. Cizanckas switched out that uniform in favor of a white shirt, dark tie, pair of charcoal slacks, and an olive green blazer. Handcuffs and firearms were hidden underneath the coat, while the shiny metal badge was replaced with a soft embroidered patch. Cizanckas even dropped the department’s use of black-and-white police cars, military stripes, and ranking. “Sergeants” were now called “managers,” while “lieutenants” became “directors.” “We should measure what we do and treat our command staff as managers,” Cizanckas told The New York Times, “not as members of a military hierarchy.”

Since the 1970s, over 400 police departments have engaged in some kind of fashion experiment. In Burnsville, Wisconsin, police chief David Couper dressed his officers in a dark blue sport coat, white shirt, and French blue trousers, making them look like airline attendants. He also discouraged officers from wearing reflective aviator sunglasses when making traffic stops. “Make eye contact,” he suggested, “make sure they know you’re a human being.” Many departments tried lightening the color of their uniforms in hopes that officers would appear less intimidating. In some suburban and countryside towns, officers wore the color of the land, such as juniper green and walnut brown. And by the mid-1980s, NYPD officers tried wearing baseball caps so they would “look more user-friendly,” according to The New York Times.

Keep reading