Even on lockdown and while working from home, in what I can only presume to be sweatpants and t-shirts, Americans love debating what others should wear to work. Last week, political blogger and Vox co-founder Matthew Yglesias responded to a tweet asking people to share their hottest, non-cancelable takes. “It would be better, all things considered,” he tweeted, “to go back to the norm where everyone has to dress up (suits/ties for men, etc.) for work at office jobs.”

Naturally, not everyone on Twitter agreed. Atlantic staff writer Amanda Mull replied: “This is incorrect and reinforces class and gender inequity, and I couldn’t find anyone who studies the modern workplace who thinks it’s a good idea.” She later added racial inequity to the list and noted that dress codes, at their core, are about who is allowed to feel comfortable in the workplace. For some, the stiff layers and layers that go into buckram-reinforced clothing represent a kind of tyranny imposed from the top down. How you feel about strait-waist-coat attire depends on whether you’re someone who makes rules or someone subject to them. In her tweet, Mull included a link to her May 2020 article for The Atlantic, where she argued that dress codes are not only wrong, they should be consigned to the dustbin of history. Let workers dress according to simple dictates, she implored, so that you treat them like adults and not “not babies at productivity daycare.”

Gurung, Cawood, and Hall all agree that the mandate for greater fairness in the workplace — spurred by nondiscrimination laws and the need to retain workers in a tight labor market — will likely spell the end of the dress code as we know it, sooner rather than later. For traditionalists, this might sound like an abandonment of pride and professionalism, but in reality, Cawood says, companies that overhaul, simplify, or drop their dress code rarely do anything but make their employees happier.

Regulating bad behavior — everything from being a smelly desk neighbor to sexual harassment — doesn’t require rules about pantyhose or facial hair. Cawood points to General Motors as a model for policing how employees adorn themselves, even if it means managers actually have to manage. The entire dress code is two words: Dress appropriately.

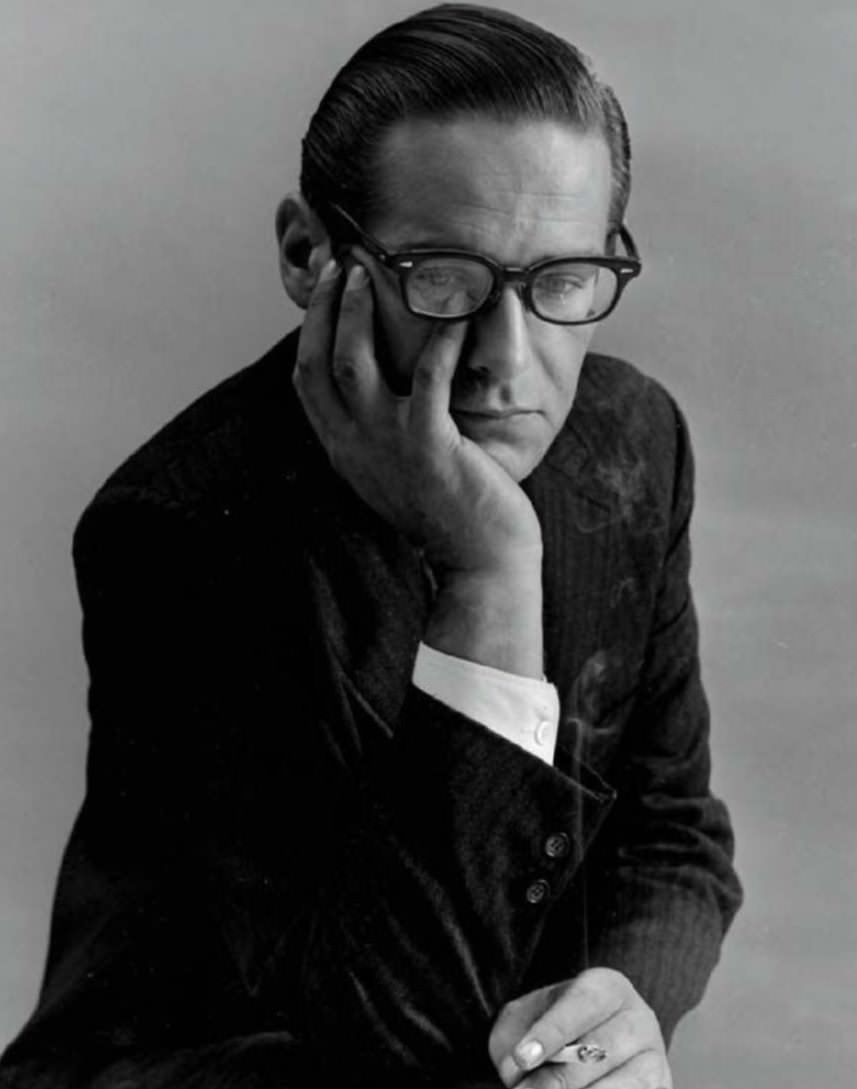

Debates over workplace dress codes mostly, but not exclusively, center around the suit. After all, no one debates whether baseball players should wear uniforms, or if UPS drivers should wear matching brown shirts and shorts, or if professional chefs should be forced to wear a toque, jacket, and apron. But the suit has been dying a slow, anguished death since the 1960s. When this fashion revolution started, it coincided and overlapped with the decade’s culture wars. Establishment types wore the suit; anti-establishment types took to white tees, leather jackets, and jeans. That shift towards what Bruce Boyer calls “rebel clothing” was the first meaningful move away from the coat and tie. The suit has been trying to wash itself clean of the stench of Establishment ever since, never with complete success.

This slippery slope started as a gentle decline in the 1960s, and now we’re speeding downhill at a breakneck pace. In 1992, Rick Miller and his PR team at Levi’s came up with an idea on how to sell more Dockers khakis. They sent out an eight-page brochure to some 25,000 human resource professionals, promising that they could remove Taylorism from the workplace by instituting an ersatz dress code. The marketing gambit worked. Since then, Casual Friday has become the full work week, and beige khakis, along with blue jeans, have mostly replaced grey flannel trousers. During the early aughts, Silicon Valley professionals chipped away at the aesthetic template of capitalism by showing up to business meetings in hoodies, jeans, and t-shirts. Suits are now a symbol of the old economy, dominated by crony capitalists and fat cat bankers. Grey marled hoodies, on the other hand, represent a new kind of meritocracy orientated around self-taught hackers, college dropouts, and self-made billionaires. (Although, when pressed, even tech billionaires have to put on their trust-me suits.)

The latest wave of dress code decline is being pushed by hot button issues surrounding gender equality and fluidity. It’s often pointed out, for example, that societies tend to police women’s bodies more than men’s. Additionally, traditional dress codes don’t always fit neatly into transgender and gender non-conforming communities. In 1989, the Supreme Court ruled that Title VII — the primary federal anti-discrimination statute — prohibits employers from penalizing employees for failing to live up to gender role expectations.

In that case, the plaintiff, Ann Hopkins, was denied partnership at the accounting firm Price Waterhouse, at least partly because her colleagues felt she was too assertive and foul-mouthed (typically considered masculine traits). Her supervisor, Thomas Beyer, told her that if she wanted a promotion, she would need to “walk more femininely, talk more femininely, dress more femininely, wear make-up, have her hair styled, and wear jewelry.” Hopkins was well-qualified for the promotion in every other regard and even secured the highest paying contract for her DC-based office. She just didn’t dress or act as feminine as some believed a woman should. Hopkins claimed she was discriminated against based on a sex stereotype, and the Supreme Court agreed.

How far does this reasoning reach? Title VII plainly prohibits employers from discriminating based on sex and gender, and it does so without exception for dress codes. And yet, in case after case, courts have upheld the rights of employers to set different appearance standards based on sex and gender. Men are required to wear suits; women may wear dresses. Women are allowed to wear cosmetics; men are not. Men must keep their hair short; women may wear theirs long. Women are required to wear high heels; men are allowed to wear flat shoes. And so forth. Some municipalities have tried to instate more specific guidelines. In December 2015, the NYC Commission on Human Rights passed a law expressly prohibiting “dress codes, uniforms, and grooming standards that impose different requirements based on sex or gender.” It’s still possible to enforce dress codes, but employers must be more careful about how they craft them.

In Britain, Nicola Thorp ignited a heel revolt in May 2016 when she reported to work while wearing chic but sensible black flats. She was shocked when her supervisor said that flat shoes are unacceptable, pointing to the agency’s “female grooming” standards at the time, and told her that she would have to buy a pair of pumps with heels at least two inches tall. When she refused and complained that her male colleagues had not been asked to do the same, she was sent home without pay. But that wasn’t the end of it. Thorp took her cause public a few months later by starting an online petition, asking Parliament to make it illegal to require women to wear high heels. The petition quickly gained over 150,000 signatures. ITV, the British television network, reported on the story, and countless women posted flat-shoe selfies online to show their solidarity with the dismissed receptionist (Labour MP Stella Creasy among them).

During their investigation, the Parliamentary committee tasked with reviewing this matter received hundreds of complaints from women who shared stories about how they’ve been required to “dye their hair blonde,” “wear revealing outfits,” or “constantly reapply make-up.” Portico, Thorp’s temp agency, required women to wear high heels and a minimum of lipstick, mascara, and eyeshadow at all times, as well as have their make-up “regularly reapplied.” Shortly after lawmakers took up Thorp’s complaint, however, Portico rewrote their dress code, dropping their heel requirement, among other things. “Employers need to focus on what drives productivity and enable their staff to feel part of a team,” Sam Smethers, chief executive of the women’s rights organization Fawcett Society, told The New York Times, adding, “It isn’t a pair of high heels.”

Even when dress codes seem sensible on the surface, such as the requirement for dark worsted pant-suits for both men and women, they can be suspiciously Orwellian once you delve into their details. In 2010, UBS was endlessly ridiculed online when it was discovered they had issued a 44-page booklet on how to dress for work. As if taking cues from style manuals, the bank told male employees that their anthracite trousers need to be pressed regularly, so they maintain a razor crease. The collar must be between 1–1.5 centimeters above their jacket’s collar and must not show any folds beneath their tie. Collar points must rest beneath a jacket’s lapels. Socks should be black and over-the-calf. White t-shirts should always be worn underneath dress shirts (me: slowly clenching fist). Suits also have to be stored on large hangers with rounded shoulders, so that clothes maintain their shape (me: slowly unclenching fist). Speaking with The Wall Street Journal, UBS spokesman Jean-Raphael Fontannaz said the detailed dress code is “in line with Swiss precision.” Still, even the financial firm eventually conceded and moved to a less restrictive code.

Dress codes have all but disappeared today, not just from the workplace but also in other areas of public life. In the 1980s, New York City was teeming with “jacket required” fine dining establishments. Now there are only a handful, and many of them don’t even enforce their own codes. This shift is often celebrated as a win for small-l liberalism (ideas of individualism, freedom, and equality that have dominated Western thought since the Age of Enlightenment). Why not live and let live, after all? Open dress codes speak to our values — clothes are superficial, individuals should be able to choose for themselves, and everyone should be treated equally.

“Dress is now open to the interpretation of the individual, rather than an institution,” fashion law professor Susan Scafidi told The New York Times. “There’s a strain of thought that says an employee represents a company, and thus dress is not about personal expression, but company expression. But there’s a counterargument that believes that we should be able to be ourselves at work because we identify so much with our careers.” She added: “We are moving into an era where personal expression is going to trump the desire to create a corporate identity.”

But is that actually true? In many ways, the decline of dress codes has just meant the rise of dress norms. Open dress environments aren’t nearly as open as some suggest. Unless you work in a creative industry and live in a big city (read: New York City), you probably can’t wear anything too fashionable or avant-garde to work. We’re not talking about Rick Owens or Kapital, but even reasonably tame designers such as Engineered Garments and Lemaire. And if everyone is wearing shorts and t-shirts, the sharpest you can look is in chinos. Open office spaces still have dress codes — they’re just softly coded as social norms, not hard written into rulebooks.

The whole situation has left many confused. “Are polos too casual?” “Are leather shoes too dressy?” “How should I dress for the meeting, office party, or interview?” When the top brass at Goldman Sachs sent out a firm-wide email announcing that the historically white-shoe investment bank will be joining the Silicon Valley crowd, they didn’t give much direction on what should replace a coat-and-tie. Management only said they want employees to dress in a manner that accords with the company’s and clients’ expectations (whatever that means). “We trust you will consistently exercise good judgment in this regard,” they wrote ominously. “All of us know what is and is not appropriate for the workplace.”

This ambiguity has made fashion one of the most talked-about topics on the internet. There are now hundreds of online micro-communities dedicated to style, and clothing comes up as a topic in places you wouldn’t even expect. Mull recognizes this in her Atlantic article, where she writes:

In subreddits dedicated to accounting, engineering, and New York City, people ask to see others’ work outfits or for descriptions of their employee dress code. In Facebook groups about weight loss or motherhood, inquiries abound on where to get an inexpensive black blazer, and who makes the best office-appropriate cropped pants. On Hacker News, a message board for Silicon Valley tech workers, a man in his late 30s recalled being humiliated by the CEO at his new job for daring to wear a button-down shirt among his cargo-shorts-clad workers. On Yahoo Answers, the world’s least qualified people have been meting out bad advice on twinsets and shin-length skirts to confused 23-year-olds since 2005.

![]()

This “pants that are not jeans” soft dress code has given men one uniform: chinos (mostly beige) with a button-up shirt (probably gingham). It’s not as attractive as casualwear could be, and not as sharp as a coat and tie. It’s not ugly; it’s just vanilla bland. You could break it, of course, but at the risk of paying a social cost. In these new ambiguous situations, dress codes have to be read off the backs of colleagues, decoded, discovered, and deciphered as part of The Culture. In a blog post titled “Inside the Mirrortocracy,” Carlos Bueno, an engineer, writes about situations when the new, cool office can be just as oppressive as the old, buttoned-up one. “The cognitive dissonance on display is painful to see. Clothing is totally not a big deal! Because we’re cool like that! But it’s plain that it biased the interviewers. The team’s disappointment upon seeing the suit was immediate and unanimous. If you truly believe that suit == loser, you can’t help it. Nevertheless, the fiction of objectivity has to be maintained, so he denies it to the candidate’s face, to us, and himself.” He continues:

Ignorance of The Culture is a serious handicap if you want to land a job out here. […] The theme is familiar to anyone who’s tried to join a country club or high-school clique. It’s not supposed to make sense. You are expected to conform to the rules of The Culture before you are allowed to demonstrate your actual worth. What wearing a suit really indicates is — I am not making this up — non-conformity, one of the gravest of sins. For extra excitement, the rules are unwritten and ever-changing, and you will never be told how you screwed up.

Even in the hiring crunches that Mull suggests may spell the end of dress codes, employers often aim to hire people they think will be a good “cultural fit.” They look for people with personalities and attributes they believe will mesh with the company’s culture. Successful job applicants know this, so they dress accordingly for the job interview and continue with this mirrortocracy long after being hired. “Don’t overdress, but don’t underdress,” Bueno continues. “You should mirror as precisely as possible our socioeconomic level, social cues, and idiom.” After making such a show of burning the old rulebooks, many offices have set up new rules that seem pretty similar.

Notably, not everyone can conform to mirrortocracy. In academia, professors are a motley crew of people dressed in musty sweaters, ink-stained oxford button-downs, rumpled chinos, and at times baggy cargo shorts. In this professional world, it’s supposed to be your ideas, not your appearance, that matters. And yet, professors are keenly aware of the need to dress in a certain way. Attire should be professional enough to secure your status as a bona fide intellectual deserving of students’ deference and respect. At the same time, you can’t seem like you pay too much attention to your appearance, lest your colleagues take that as a sign of a lack of seriousness or intellectual ability. So it’s mostly administrators who wear suits, while harried, overworked, and underpaid professors have mostly given up on the coat and tie to signal that they’re so committed to the world of ideas, they can hardly spare a thought on what to wear.

However, women and BIPOCs often have to conform to more traditional notions of respectability, which means putting on more professional-looking attire. “Behind our workplace wardrobes lies the nexus of inequalities that structure the university,” Shahidha Bari wrote in The Chronicle of Higher Education. “The female professor who looks younger than her years knows this; she thinks hard about how to connote her age and command the respect her learning deserves. So too does the recently graduated teaching assistant who wants not to be mistaken for a student any longer, but to be seen by colleagues as an equal in the competitive job market.” Yet, if men dress up, they risk standing out as being overly self-aware about their appearance. In a room full of men in chinos and chunky sweaters, a more professional dressed woman may come across as stuffy or scold-y. It’s a lose-lose situation.

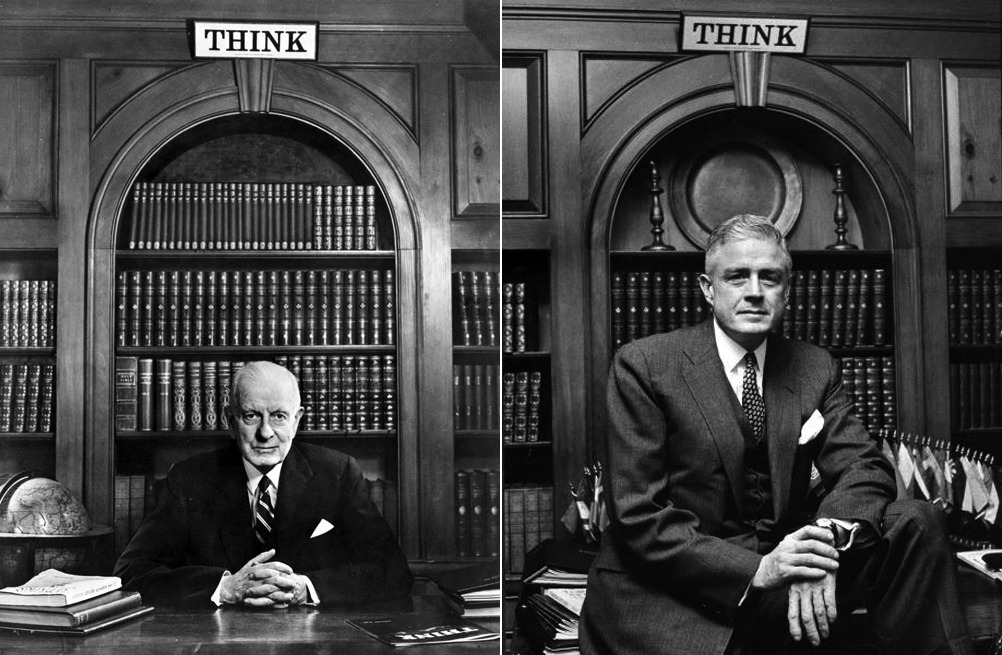

Today, the suit is a rigid symbol of elitism, formality, and conformity, but there was a time when it was considered a more democratic form of dress. From the 1860s onwards, London, the home of the suit, was split into two sartorial classes. The first were those elite gentlemen who favored a combination of a black morning or frock coat reaching to their knees and striped wool trousers in black and grey and a silk top hat. This was the uniform of the cosmopolitan elite, such as members of Parliament, barristers and judges, financiers and stockbrokers, and medical doctors. This fashion continued until the early 20th century, when it ossified into a kind of formal livery dress worn to Court, or at special social occasions such as weddings and funerals (not unlike the suit today).

At the turn of the century, however, the suit — back then known as the lounge suit — was a workingman’s uniform favored by those on the lower rungs of the social and professional ladder. Clerks, clergymen, teachers, and journalists wore a short coat paired with tapered trousers and a high waistcoat, all made from the same drab and single-pattern cloth. For a time, the suit served as a bulwark against the more ostentatious, elite, and “cosmopolitan” registers of dress.

At the turn of the century, urban elites looked down on the suit in the ways that suited men today look down on cargo pants. But the suit eventually found a broader market through its affordability and varied connotations. It was a more relaxed alternative to the frock coat, but still smart enough for the public. Through its association with the working class, it had a certain rugged romanticism. Its mournful and monotonous drabness also spoke to some people’s anti-materialistic world views. In his book The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England, John Styles argues that religious values for modest dress helped mainstream the plain and straightforward suit into masculine wardrobes. The Methodists, led by John Wesley, encouraged followers to eschew ornamentation and extravagance. Quakers also ended meetings with discussions about the troubling lapses some wayward members had into selfish fashionability. “Buy no velvets, no silks, no fine linen, no superfluities, no mere ornaments, though ever so much in fashion,” instructs Wesley’s Advice to the People Called Methodists, with Regard to Dress. “Wear nothing, though you have it already, which is of a glaring color, which is in any kind of gay, glistering, showy; nothing made in the very height of fashion, nothing to attract the eyes of bystanders.”

Change really came during the industrialization periods of Britain and the United States, when ready-to-wear manufacturing made the suit both more affordable and an optimistic symbol of snappy progress. The suit stood for all things modern — democracy, equality, and industry. “No more tangible expression could be found of the regularity — and notion of equivalence — these broker citizens sought to bring to the industrializing market and to the social relations growing up around it than the uniformity of their ‘well broad-clothed’ appearance,” Michael Zakim writes in his book Ready-Made Democracy. “The monochromaticity of the dark suits and white linen of their single-priced ‘business attire’ constituted a capitalist aesthetic. It helped these individuals to recognize each other’s ‘utilitarian’ fit as their own, and made every body a reproduction of the next one […] They constituted an industrial spectacle that brought social order to another otherwise disordered situation.”

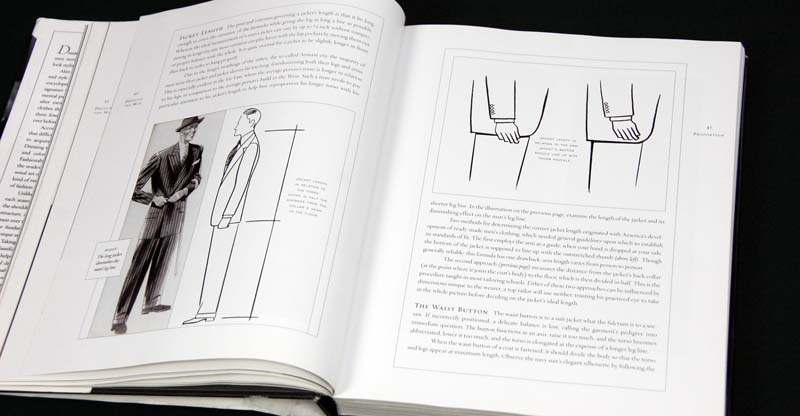

So, what have we lost with the decline of dress codes? Most superficially, a garment that looks flattering across a wide range of body types. Unlike casualwear, tailored clothing is made from multiple layers — padding, haircloth, and canvas, carefully stitched together to create the illusion of a more V-shaped torso. This is no small thing, especially as you get older and find yourself getting paunchy. A well-tailored jacket broadens the shoulder line and makes the waist look smaller by comparison.

Second, traditional tailored clothing is relatively more anchored, which keeps dress norms from swishing around in the tides of fashion. You no longer have to worry about whether your chinos are cut in the socially correct silhouette, if your patterned shirt looks outdated, or if your shoes signal the wrong thing about your character. Without a formalized code, dress culture can be increasingly petty, judgmental, and unfair. Cultural insiders have the upper hand, and dress culture can change once you catch wind of what to wear (as Georg Simmel notes in his 1904 essay, fashion is a game of imitation. The supposed “lower classes” will wear things to imitate their social betters, at which point the elites will move on to distinguish themselves from the hoi polloi). The literal definition of privilege (privilegium) comes from the Latin terms for private law. One of the benefits of having a dress code is that the law is written down for all to see and understand. It takes away the mystique, where only some are “in the know.”

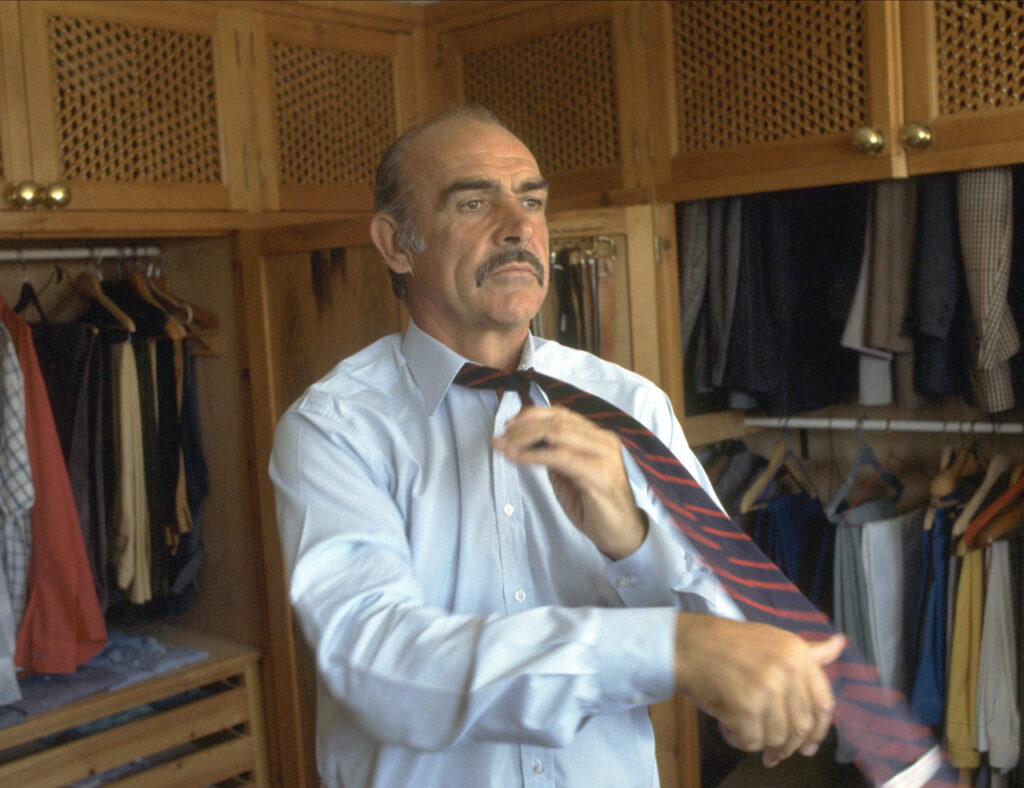

Dress codes also allow you to signal that you’re serious about your work. This is not just a matter of pride and professionalism, but also a matter of allowing less-privileged groups to climb up the professional ladder. The people who benefit the most from casual Fridays are those who have already made it. Bill Gates can countersignal all he wants in sneakers and jeans, as recognition is obvious, if not a mere Google search away. But what do you do if you’re not Bill Gates? “If you’re twenty-four years old and looking to get ahead, it can be tougher,” economist Tyler Cowen wrote in his book The Complacent Class. “There isn’t such a simple way to visually demonstrate you are determined to join the ranks of the upwardly mobile. Looking smart on ‘casual Friday’ may get you a better date, but the boss will not sit up and take notice. In other words, a culture of the casual is a culture of people who have already achieved something and who already can prove it. It is a culture of the static and the settled, the opposite of Tocqueville’s restless America.”

It’s undeniable, however, that critics have a point. In forcing everyone to wear the same thing, the suit suppresses individuality (assuming you can also express individuality in open offices). The suit is relatively stable, but it’s also only so because it derives its traditions from the stability of the British upper-class lifestyles. This is a world of mostly men’s activities, such as hunting, horse riding, a love for country homes and their comforts, London business meetings, military duty, and elite schooling. In the last 100+ years, the meaning of classic men’s dress has changed through its adoption by other groups (e.g., Black jazz musicians), but the legacy of British upper-class lifestyles remains primary. It’s also still mostly masculine. The danger of traditional notions in dress is their tendency to affix concepts of identity.

However, I found it interesting to read Katie Manthey’s interview with Elroi Windsor, a queer, white, sociology professor with a punk rock past and a number of tattoos. When Manthey asks Windsor what genderqueer professional dress means in the context of a small women’s college in the South, Windsor replies: “What it means to dress professionally is being conscious of my identities, my body, just strategically using different kinds of dress in different contexts. So for me, ‘profesh‘ is how I want to appear to students as somebody who does know what they’re talking about. But again, it’s professional attire embodied through this queer, transgender person that isn’t totally normal, isn’t totally gender-normative, business-normative, professional normative. […] In choosing this very traditional business attire, embodying it through a marginalized gender embodiment, it’s not like I’m dressing in traditional professional attire. By virtue of my engendered embodiment, that traditional business attire is queer.”

Dressing professionally doesn’t mean you have to negate your identity or individuality. The template has been endlessly remixed by different groups and can continue to evolve in its meaning. Mostly, I think this is a good problem to have. The decline of dress codes is part of a broader question about how we negotiate different cultural identities in a common society. Office dress codes are messy right now, but they’re relatively trivial in the grand scheme of things and will hopefully one day work themselves out.

In the early 1990s, Stuart Hall, a Jamaican-born British cultural theorist, wrote about the challenges thrown up by conflicting definitions of culture, community, and nation. As Hall notes, “common culture” and “common society” are two different things, and this is something we should embrace, not run away from. “It should not be necessary to look, walk, feel, think, speak exactly like a paid-up member of the buttoned-up, stiff-upper-lipped, fully corseted and free-born Englishman, culturally to be accorded either the informal courtesy and respect of civil social intercourse or the rights of entitlement and citizenship,” he wrote. “Since cultural diversity is, increasingly, the fate of the modern world, and ethnic absolutism a regressive feature of late-modernity, the greatest danger now arises from forms of national and cultural identity — new or old — which attempt to secure their identity by adopting closed versions of culture or community and by the refusal to engage — in the name of an ‘oppressed white minority’ (sic) — with the difficult problems that arise from trying to live with difference. The capacity to live with difference is, in my view, the coming question of the twenty-first century.” For those of us obsessed with clothes, the question is what an ideal workplace would look like, both in social order and dress culture.