Three years ago, I was in an elevator in a San Francisco hotel with Agyesh Madan, co-founder of Stoffa, after he finished a trunk show. We were on our way to get lunch at a cafe across the street. Madan, who’s always immaculately dressed, was wearing a grey suede double rider with a pair of cream-colored trousers, a dark blue Camoshita pullover, and some beat-up Belgian loafers. As we exited the hotel lobby, Madan told me about his design process. “We spent years developing this jacket,” he said of the double rider he was wearing. “For everything we create, we go through cycles of prototyping and testing, as I want to be confident of the things we offer to our customers.”

The things Stoffa offered at their trunk show that day in 2017 — including the luxurious faded chevron scarves, lightweight Tuscan leather bags, peached cotton trousers, and core line of made-to-measure leather outerwear — are still with them today. In an industry that reinvents itself every season, with designers wiping the slate clean and starting anew, Stoffa is a remarkable example of slow fashion. Not only does the company take its time to incubate ideas and develop new products, but items stay in their collection for years and years. In this way, consumers don’t feel pressured to continually replace things they already own.

Over the years, I’ve admired Stoffa’s approach to slow fashion, which starts with its product development process and extends through to their repair service. A couple of weeks ago, I talked with Madan and his business partners over the phone about their latest capsule collection. We also discussed whether sustainability is possible in an industry that relies on selling people new clothes every season.

In 1786, the editors of Magasin des modes nouvelles, one of the first fashion magazines published with any regularity, noted with some concern that it took a week for their publication to reach bookstores in Germany and two weeks to reach subscribers there. The editors feared that, by the time their publication got into people’s hands, the contents would be out of date. “You know that in Paris,” they wrote, “it is rare that a fashion exists beyond three weeks or a month, in a fixed and unvaried state. Who would want an outdated fashion?”

This dynamic has only worsened with time. In the last 15 years, the fashion industry has moved from a two-season production schedule to four (mainly through the addition of pre-fall and resort, the second of which is sometimes called cruise). If a brand offers menswear alongside womenswear, it may have upwards of six collections per year. If they’re a large, historic label, such as Chanel, Dior, or Givenchy, there may also be couture. Shortly after he stepped down from his post as the Creative Director at Dior, Raf Simons complained that this frantic schedule leaves little time for thinking.

“When you do six shows a year, there’s not enough time for the whole process,” he explained to Business of Fashion. “Technically, yes — the people who make the samples, do the stitching, they can do it. But you have no incubation time for ideas, and incubation time is very important. When you try an idea, you look at it and think, ‘Hmm, let’s put it away for a week and think about it later.’ But that’s never possible when you have only one team working on all the collections.” Simons says this pressure ultimately affects the quality of the designs. When asked what kind of ideas end up in collections, he shrugs. “Stupid things. […] It can be stupid things, like a certain button. But I’ve been doing this my whole life. The problem is when you have only one design team and six collections, there is no more thinking time.”

At some companies, it would be a tender mercy if designers only had to produce six collections per year. Zara makes a staggering 24 collections over the course of 12 months, which amount to a total of about 30,000 new products. “We have new garments coming into the stores almost every day,” says Karl-Johan Persson, CEO of H&M. “If you go into an H&M store and come back two days later, you will find something new.” H&M produces so much clothing, it reportedly sat on a $4.3 billion pile of unsold inventory in 2018. Fast fashion companies don’t leave much time for ideas to incubate, but of course, they also don’t need to. Their designs are ripped off from runway shows or cobbled together with the help of analytics about the latest trends.

This new pace in fashion is having a disastrous effect on the environment, which has forced some companies to reform their practices. There are often waist-high recycling bins at the back of stores such as Levi’s, Zara, and H&M, where you can drop off your unwanted clothes in exchange for a discount card on your next in-store purchase. Companies promise to turn those old items into scrap material, which will, in turn, go into making more products. Ralph Lauren and Adidas recently introduced earth-friendly polo shirts and tennis shoes wholly made from recycled plastic bottles. Yesterday, I received an email from Nike about their latest must-have Jordan, which supposedly represents the brand’s “unique take on circular design principles.”

Critics, however, say that the fashion industry is just trying to greenwash its wasteful practices. “The reality is that only one percent of clothing is recycled in the literal sense of the word,” Elizabeth Cline, author of Over Dressed, told the CBC. “The reason why H&M is focusing on textile recycling is because it’s an easy sustainability win for them. It doesn’t involve them changing their production model at all.”

Nicholas Ragosta, a business partner at Stoffa, says that sustainability discussions all too often focus on just one dimension — recycling, efficiency, emissions, etc. The onus is also often on just brands. “We feel that true systemic change can’t happen until it happens at every point in the process,” he told me over the phone. “It’s absolutely the brand’s responsibility to look at how their business is set up. What are your cost structures and pressures for growth? What materials are using? At the same time, there are other parts of this system. Consumers have to think about how they’re building a wardrobe. If you purchase something you really love, the item will last much longer in your wardrobe. And media companies need to think about the volume and angle of their press coverage. Stories that are all about hype and the latest drop miss the point.”

“We’ve tried to set up our business in such a way so that all the incentives are pointing in the same direction,” Ragosta added. “That means how we produce things, talk about our products, and interact with customers. A few years ago, Vanessa Friedman wrote a line in The New York Times that has stuck with me: ‘sometimes a selective drip is more effective than an open tap.’ We don’t release things for the sake of releasing them, and we try to be thoughtful about our design process. Sometimes it feels like the environment is a hot topic right now, and brands are trying to capitalize on that conversation without addressing their business model.”

In a slower fashion model, brands would ideally release fewer and more thoughtful collections. For example, Stoffa has only introduced a handful of new items this year, not including the new fabrics available for its trousers, knit, and outerwear. There’s the fluid suede overshirt they debuted in March, just before the lockdown, which is specially backed with a paper film to make it easier to slip-on. Then they have a small line of easy-care, machine washable trousers cut from their signature basketweave cotton and made with a self-belt and inverted box pleats. Last month, they introduced two lightweight cashmere sweater models designed for brisk autumn weather.

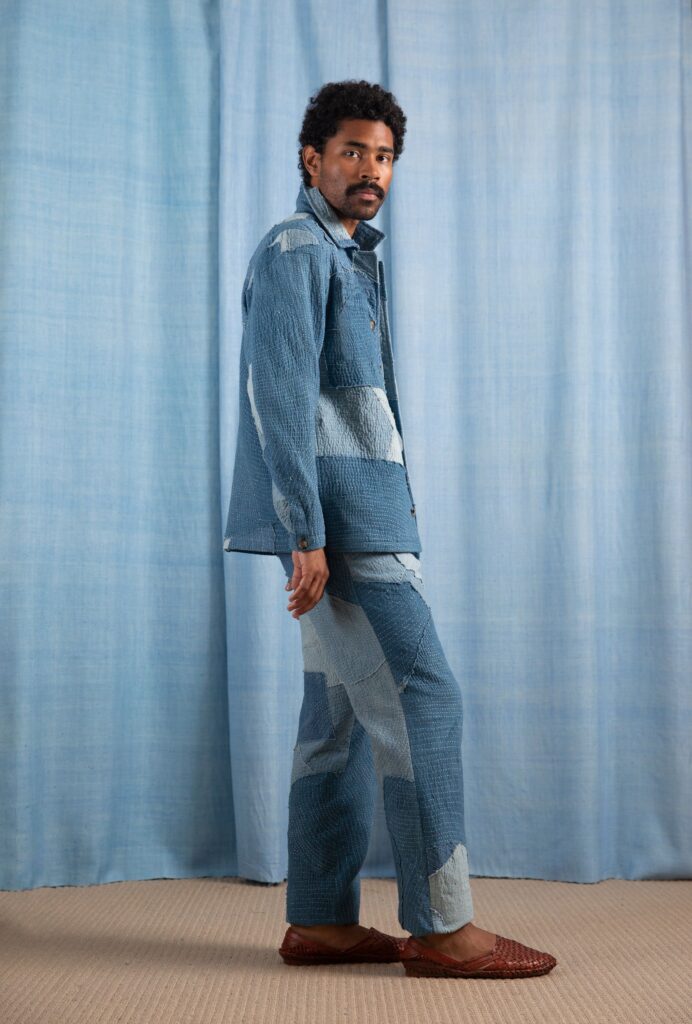

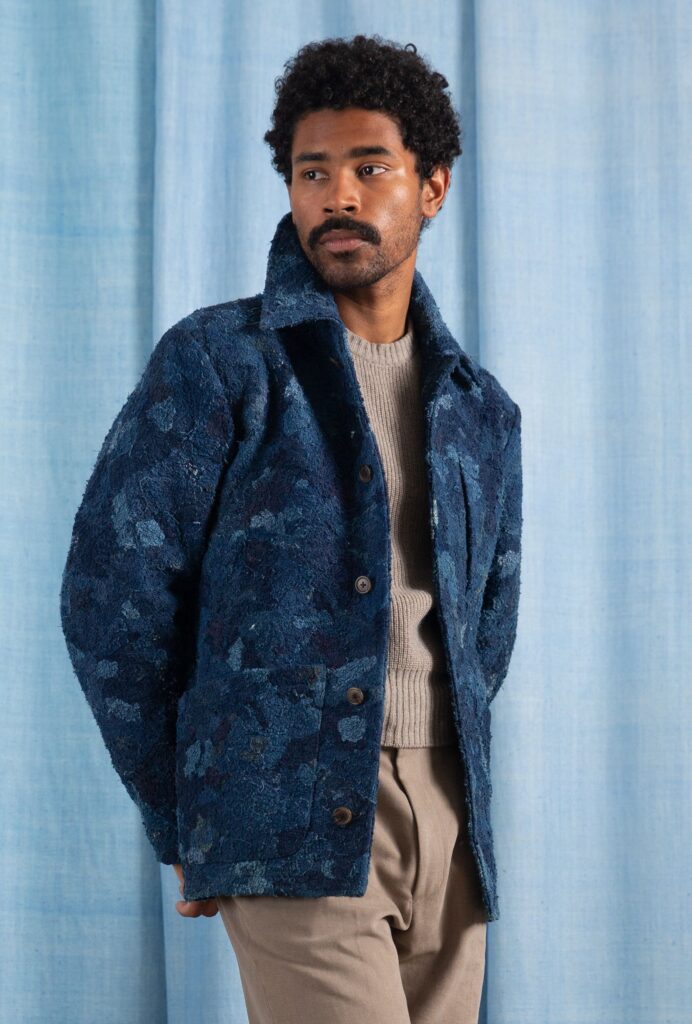

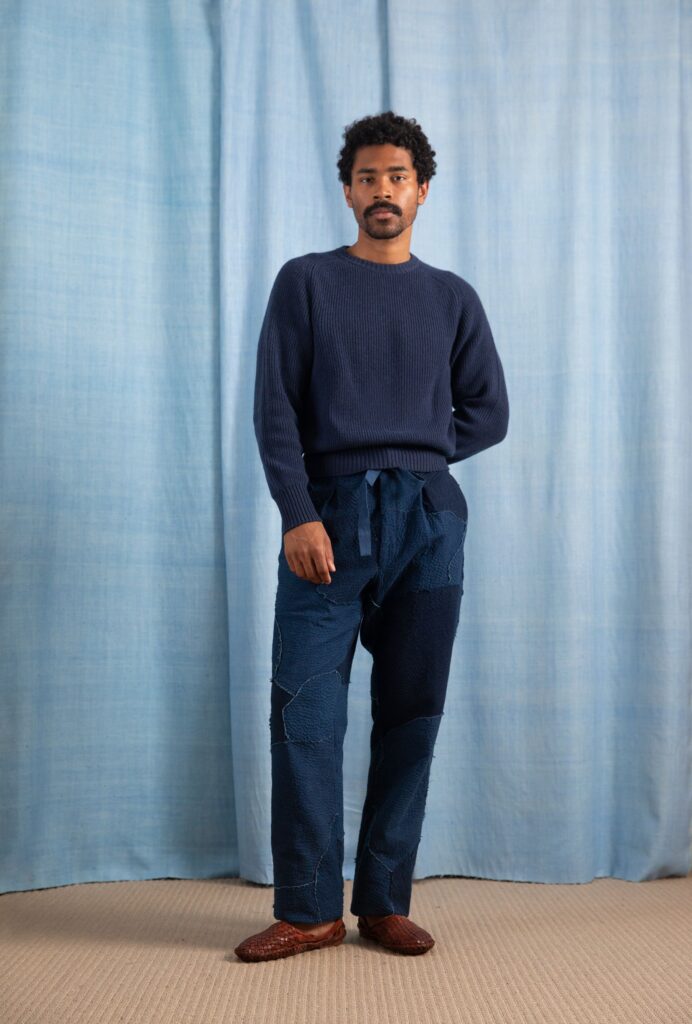

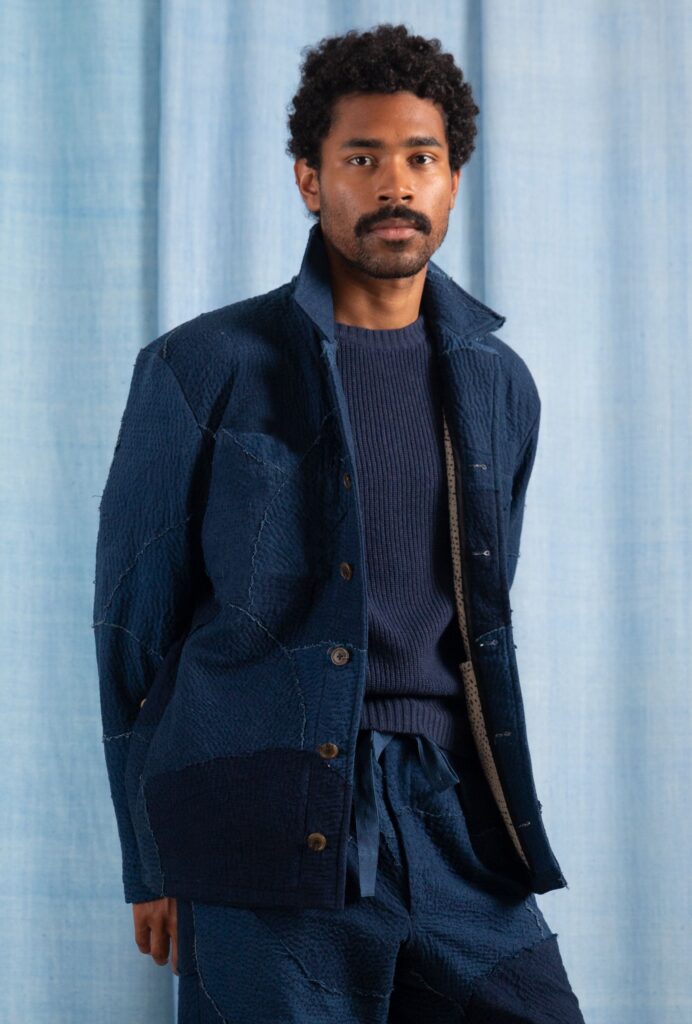

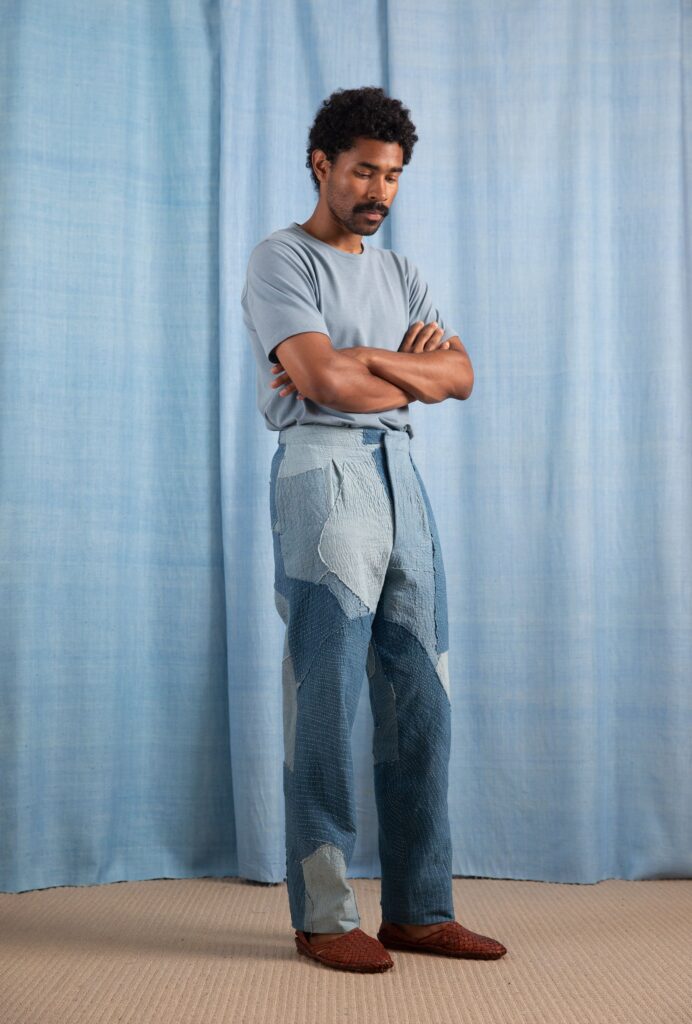

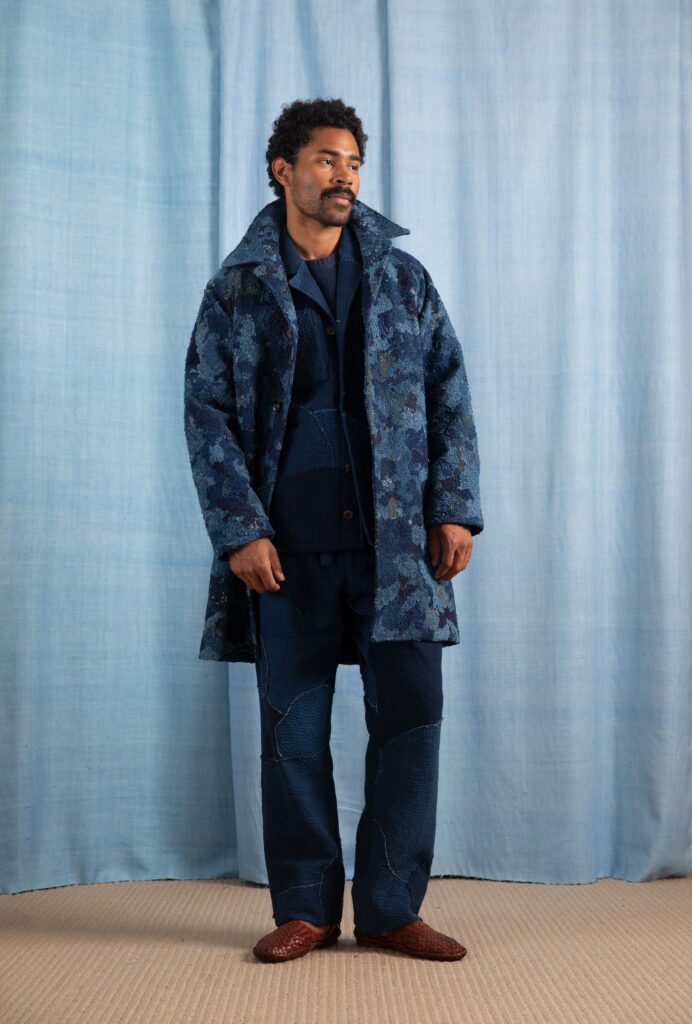

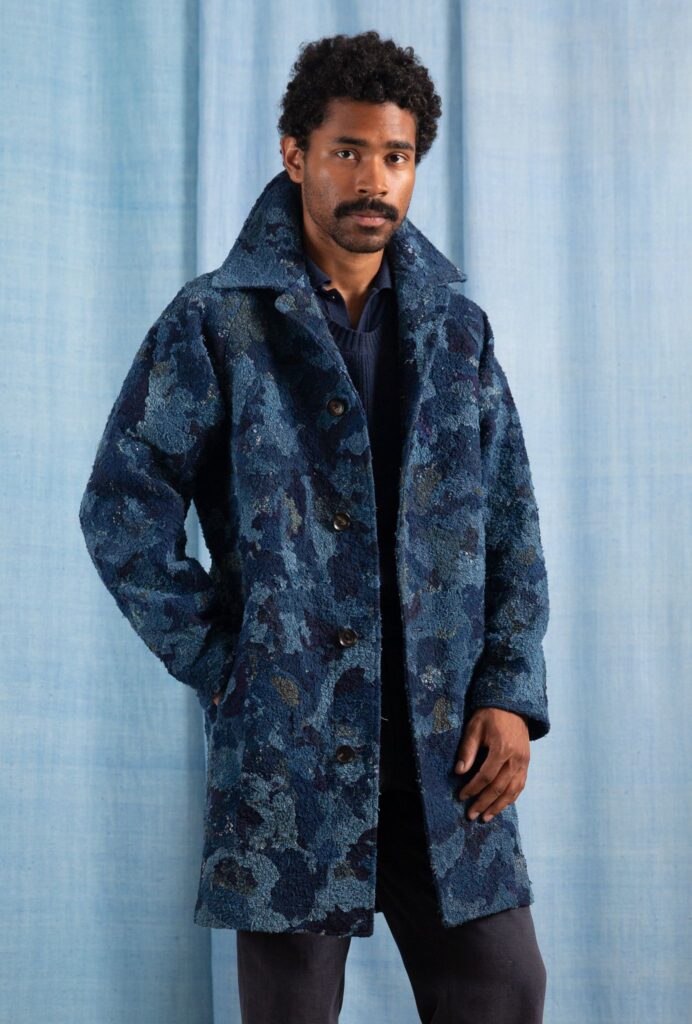

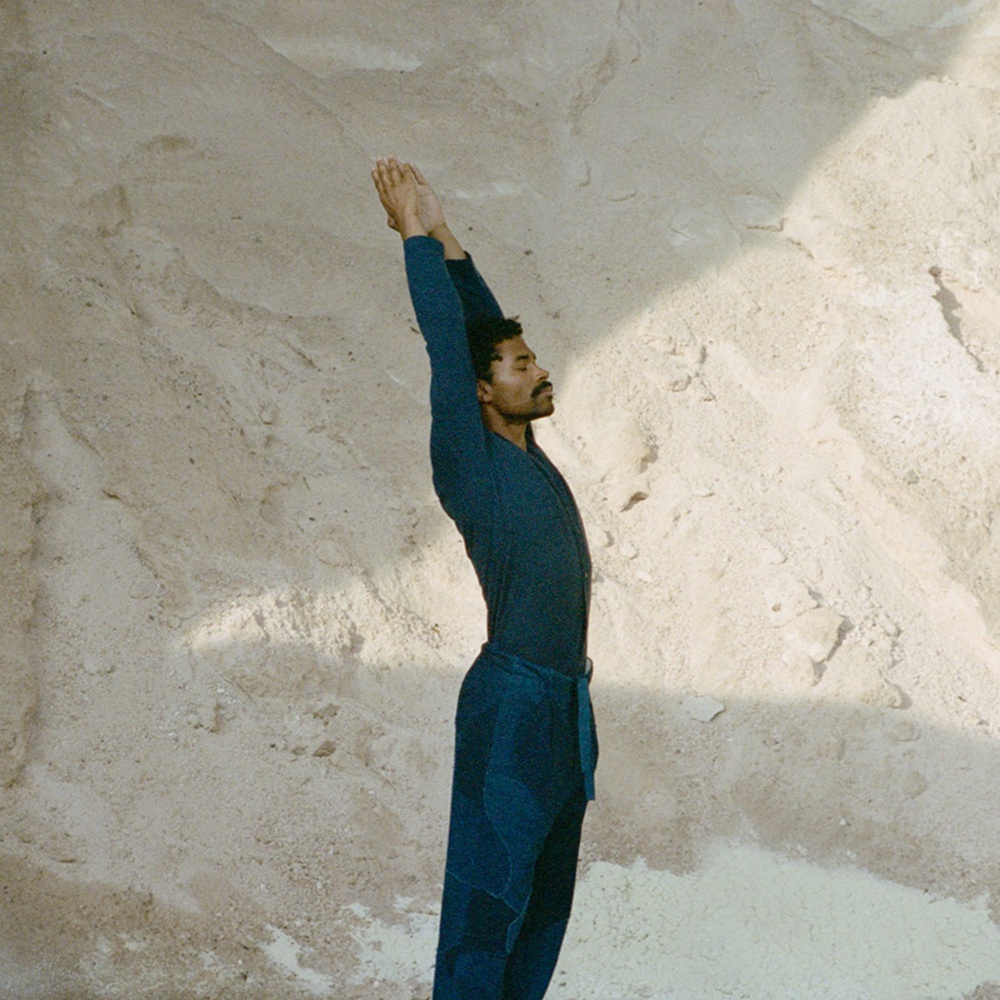

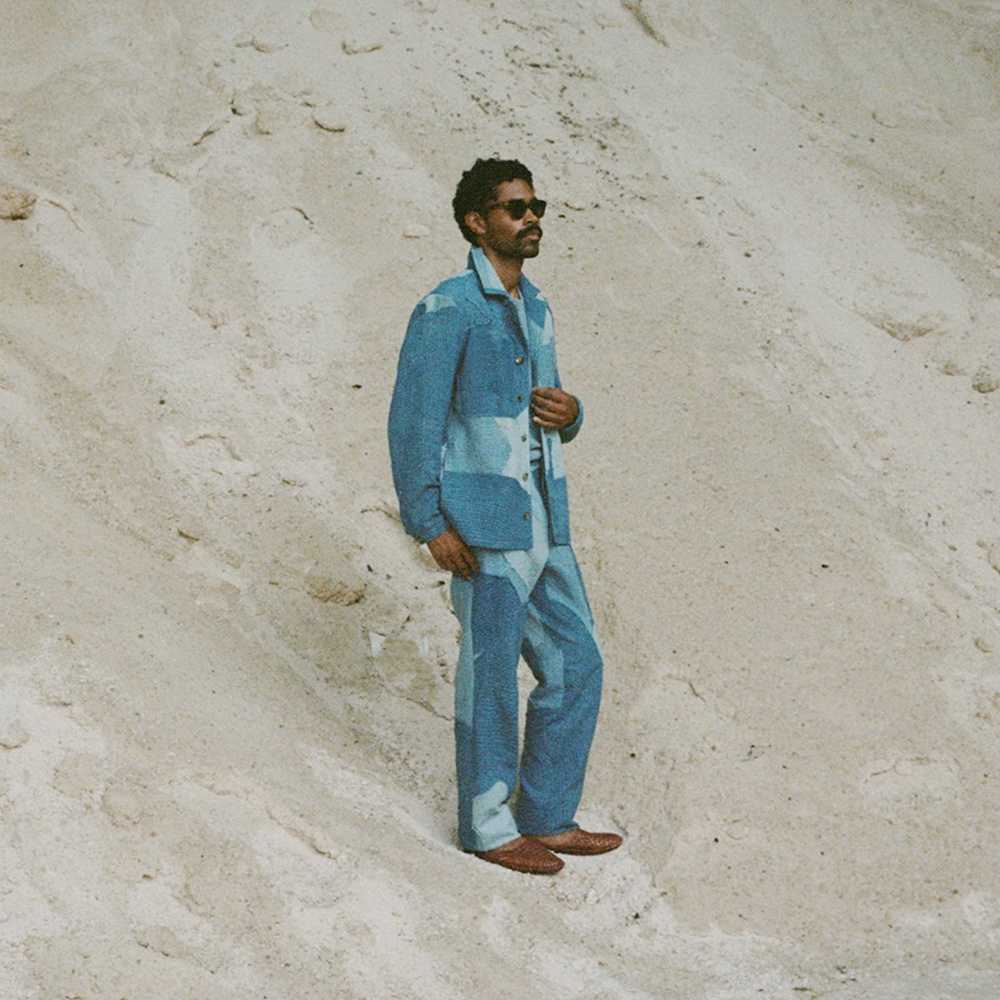

Their latest drop is a six-piece capsule collection made in collaboration with the slow fashion label 11.11 (pronounced eleven eleven). The drop includes raglan-sleeve overcoats, comfy shirt jackets, band collar shirts, drawstring trousers, and some accessories. Each piece is entirely made from indigo-dyed cotton remnants that the 11.11 team has been saving for over a decade. The remnants were transformed into beautifully textured, patchwork fabrics using various embroidery and stitching techniques, then sewn together in Italy to create the garments.

In her latest book, Fashionopolis, veteran style writer Dana Thomas examines the fashion industry’s rampant labor and environmental abuses. As an antidote to fast fashion, Thomas suggests “slow fashion,” which is like a clothing equivalent of the slow food movement. Slow fashion is “a growing movement of makers, designers, merchants, and manufacturers worldwide who, in response to fast fashion and globalization, have significantly dialed back their pace and financial ambition.” This means making clothes on a smaller scale, perhaps even domestically, and using locally sourced materials where possible. There’s a lot of faith placed here on the idea of “a circular — or closed-loop — system, in which products are continually recycled, reborn, reused. Nothing, ideally, should go in the trash.”

The clothes in Stoffa’s collaboration with 11.11 are a little outside of what could be called “classic menswear,” but not that far from labels such as 18 East, 45rpm, and Blue Blue Japan (which can be described as “classic adjacent”). They’re also an example of how “slow fashion” production practices can be implemented in menswear. For the last seven or eight years, 11.11 has been practicing what they call “circular production.” “We don’t throw anything away,” says 11.11 co-founder Mia Morikawa, “because we know what goes into making cloth.”

At the heart of this collection is the cloth, which is made from a ten-year archive of scrap material that had been sitting in the backrooms of some craft clusters that 11.11 has employed since their founding. The material was wholly made in India from start to finish. After the cotton fibers were grown in Gujarat, they were sent to West Bengal for hand spinning and hand weaving, and then Puducherry to be hand-dyed in natural indigo. By keeping the entire textile production chain domestic, 11.11 can cut down on shipping and thus greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s the recycling process that makes the material exciting.

When clothing is made, a pattern maker or cutter will lay out their pattern pieces on a large, uncut length of fabric. This process is similar to how a baker would cut out cookies from a rolled sheet of dough: both arrange their pattern pieces in such a way to maximize yield. However, with cookie dough, any scraps can be balled up and rolled out again to produce more cookies. When you make clothing, the fabric remnants are typically thrown away.

11.11 practices a “zero waste” philosophy, where they first cut large panels for items such as shirts. The remnants from that process are then sewn together in a patchwork style, sort of like an Indian version of Japanese boro (in India, this cloth is known as kantha). Here, scraps are sewn on top of each other in a three-layer construction — scrap upon scrap, and then backed by a cotton muslin for structure. The materials are secured to each other with a running stitch. “Normally, these stitches run vertically or horizontally in a straight line,” Madan explains. “But the way 11.11. does it, the stitches emphasize the organic form of the cloth itself. The stitching curves along with the patches, making the lines look like ripples in water.”

The remnants from that patchwork process are also turned into new materials. These scraps, which are necessarily smaller than the patchwork pieces themselves, are made into chinidi, an Indian word for “torn cloth.” Small fragments are sewn onto each other using a continuous embroidery stitch, which results in a boucle-like texture. With their tonal blue layering, 11.11’s version of chindi looks like a modern, textured version of camouflage. Finally, even the scraps from this process aren’t wasted. The leftover materials are boiled and then pulped into paper, which 11.11 turns into soft white and slate blue notebooks.

Stoffa is using these recycled materials for its specialty line of made-to-order garments, which are produced in Italy. The Macca shirt, an original 11.11 design, is made from an unbroken length of handspun, hand-loomed cotton that has been hand-dyed in natural indigo. The quilted kantha cloth was used to create trousers and unlined shirt jackets. Finally, the boucle-like chindi cloth, which is surprisingly hefty, was transformed into raglan-sleeved topcoats, chore coats, and laptop covers. The order window for these items is open on Stoffa’s website until October 2nd. The notebooks are available now at 11.11.

Over 90 percent of Stoffa’s revenue comes from selling made-to-order and made-to-measure products. Since these items are only made upon ordering, that means they’re bought in advance, sent to production, and then shipped about a month or two later. This “slow fashion” process runs counter to the instant gratification experience of fast fashion and most regular fashion. But it also solves fashion’s biggest inefficiency. In the traditional wholesale model, garments are produced many months in advance and then distributed to retailers. It’s estimated that this costs the US retail industry as much as $50 billion in dead inventory each year. It’s not just the cost of unsold inventory, either, but the cost of holding such stock in warehouses and brick-and-mortars stores — real estate that could be put to better use. (Like affordable housing!)

“In a world like fashion, efficiency can sometimes be a dirty word,” Lauren Sherman recently wrote at Business of Fashion. “But one of the biggest business problems the industry faces is the cost of excess inventory that goes unsold at the end of the season, resulting in waste that erodes profit margins. […] In a trend-driven sector like fashion, perfectly aligning supply and demand is nearly impossible, especially when you have to place bets on product up to 9 months before it hits the sales floor.”

Morikawa believes that a “zero inventory” model may be the wave of the future. “Especially nowadays, it’s hard to imagine what the world will look like in six months,” she says. “A made-to-order model feels more aligned with our democratic values. Production is driven by the audience, not the designer. It’s almost arrogant for a designer to think they can anticipate people’s needs in the future.” When a consumer selects something for MTO or MTM, they’re also taking a more active and thoughtful role in the shopping process, which presumably changes their relationship with clothing. Ragosta believes this is one of the reasons why Stoffa sees such a low return rate.

For Stoffa, slowness isn’t just a marketing gimmick, but something deeply embedded in how they produce, sell, and talk about clothing. In a recent email, they published a conversation between them and the Swedish tailoring label Saman Amel. Both companies discuss the importance of slowing down the way clothes are marketed and sold. Stoffa also offers a lifetime repair service for all their clothes, so consumers don’t have to throw away things once they’ve become threadbare or stained. For every fabric they’ve offered, Stoffa keeps a few meters on hand so the company can seamlessly patch-up holes and replace stained panels.

But are these practices scalable? Can a company the size of Zara implement zero waste and zero inventory? Could they offer repair services? “I think the potential for scale isn’t just about scaling one company, but a thousand companies,” Madan says. “We don’t do every style and aesthetic, and I don’t want to take away the personal expression in clothing. The future isn’t about us being the king of the world, but about how a thousand brands can make clothes very slowly. If you have a farm-to-table restaurant, you may only have three locations. But if the idea of farm-to-table restaurants becomes popular, and more businesses operate in this way, that’s when you can see real change.”

(photos via Stoffa, 11.11, and Nike)