Summer Tweed and Slubby Oxford

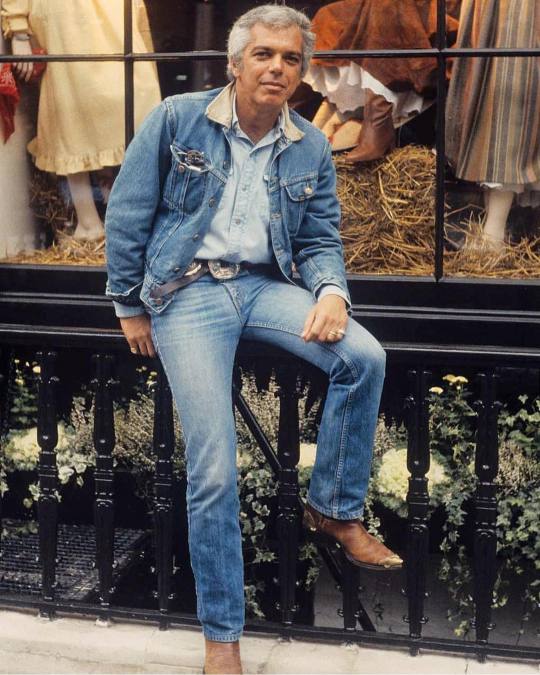

A couple of years ago, after having no success trying to find raw silk jacketing, I organized a custom-run of linen-silk fabric modeled after Taka’s jacket pictured above. The cloth mimics the slubby texture of raw silk jacketings from yesteryear — which are impossible to find today outside of vintage fabric vaults — but it wears cooler and is readily available. I call it summer’s tweed.

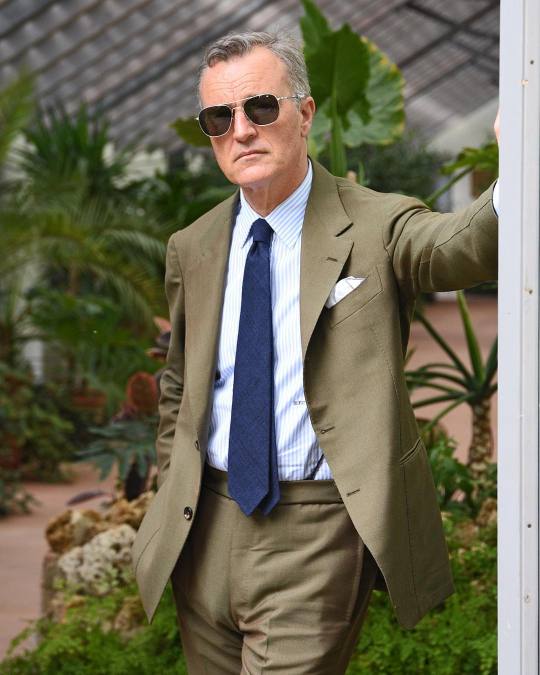

I never anticipated it would be such a hit. Since running the fabric, it’s appeared in GQ, The Sartorialist, and Permanent Style. Bespoke shoemaker Nicholas Templeman wore it in a Last Magazine feature. Dionisio D'Alise, the head cutter at Sartoria Formosa, sometimes wears it at fittings. Anderson & Sheppard trained coatmaker Lee Oxley says he loves the cloth. For clients of custom tailors, finding an interesting spring/ summer fabric can be tough. They typically don’t have the same textures or patterns that make fall/ winter clothes so appealing. This one, however, has the visual texture of your favorite tweeds, but is airy enough for spring/ summer weather.

It’s also a favorite of readers. After having organized multiple custom fabric runs at this point, I’ve received more emails about this one than any other. Those who pre-ordered the fabric have written in to say how much they like their resulting garments. Those who missed out have asked if the cloth will be offered again. So, I’m doing one more run of summer tweed — this time with a special collaboration with Spier & Mackay.

Keep reading