In an interview with The Telegraph, Patrick Grant of Norton & Sons and E. Tautz once described fashion as being an “ever-moving feast.” I often find that the quick-paced nature of fashion – where things are constantly being created and destroyed – makes the field endlessly interesting. There’s always something new, something different, something to talk about. And while my taste in tailoring leans classic, I like casualwear that’s a bit more progressive and experimental.

For the past few years, I’ve been doing these annual posts where I roundup new brands. To be sure, not all of them are actually new – many have been around for years – but they’re new to me. Here are seven labels I recently discovered. And while not all of them sell things I’d personally wear, I find them inspiring in some way. For more of the same, you can see previous years’ posts here, here, here, and here.

I often wonder if online shopping and Instagram are changing the ways we interact with fashion and, in turn, how designers design. In the past, it was easier for brands to stand out by using quality materials, cutting their clothes interesting ways, or incorporating subtle details into their garments. When you’re shopping in a store, for example, you can appreciate the chalky hand of ancient madder – something Paul Winston at Chipp Neckwear once described as feeling like a horse’s wet nose. But online, the material gets flattened out and can look like any other silk when viewed as a jpeg.

I imagine that puts brands such as Phlannèl at a disadvantage. Phlannèl is a relatively new Japanese label specializing in a kind of cozy minimalism. They have slouchy sweaters made from soft, slippery baby alpaca yarns; loosely cut shirt jackets modeled after something French Army hospital workers used to wear. Their over-long, point-collar button-ups are constructed from richly colored, yarn-dyed cottons. The chunky herringbone topcoats are made from an unusual tweed weave. The clothes look so comfy, like something you’d wear while eating a bowl of steamed fish and freshly cooked rice. But to appreciate any of it, you have to pause and take a closer look. You can find Phlannèl at Bloom & Branch and Namu Shop (the second being a sponsor on this site).

In the last ten years, many factories have had to become brands. Private White VC, for example, is a 100-year old manufacturer based in Salford, England. They’re a stone’s throw away from Manchester, a city once known as Cottonpolis because it was where a third of the world’s cotton was spun. Today, the region has seen its manufacturing sector decimated by cheaper imports – much like you’d find in any post-industrial economy – but Private White VC has managed to plug away with pattern-cutters, button stitchers, and machinists. Much of this is due to the fact that they’ve developed their own brand, which they sell directly to consumers. The same has happened at other factories – Drake’s, Bresciani, and Simonnot-Godard most notable among them.

Across the Anglo-Scottish border in Annan, you’ll find a similar story at Esk Valley Knitwear, a fifty year-old knitting mill that has long made private-label sweaters for the likes of Nigel Cabourn. A couple of years ago, they also branched out with their own label, which is simply called ESK. The garments are exceptionally made, but like any brand, ESK has had to figure out what to do with unsold inventory.

I haven’t confirmed this, but I think old season stock is being offloaded through a more modestly presented website called Genuine Scottish Knits. The two companies share the same address and telephone number, and the knits look awfully alike. The quality may be slightly different – I haven’t handled GSK’s garments – but the prices are very attractive. The plain-colored lambswool-Shetland crewnecks, for example, go for £195.00 at ESK’s site. On Genuine Scottish Knits, they’re a mere £59.00 if you’re willing to take an older season’s color. Flecked Donegal sweaters are as low as £69.00; shawl collar cardigans are a little more. You can find even more of their offerings on eBay.

Again, fair warning: I haven’t handled these in person and don’t know how the qualities compare. You may also want to email them for sizing advice. In the US, a size 40 sweater usually means it was made for someone with a 40″ chest. In the UK, however, a size 40 sweater sometimes means the chest was made 40″ all around (so better for someone with a 38″ chest). Best to double-check with the company.

Allevol isn’t new, but they’re new to me. About fifteen years ago, Takashi Okabe, who doubles as an editor and a journalist in the Japanese magazine industry, started a vintage workwear label. The garments take after the kind of hard-wearing, practical clothes that define British workwear, but they’re updated in ways that allow them to be worn in either repro-heavy looks or ensembles that simply involve everyday jeans and boots.

This mountain parka, for example, is modeled after a 1940s British Army SAS parachutist smock. It features a two-way zipper, drawstring waist, and an insulated lining. The jacket isn’t cheap by any means, but for a piece of outerwear that was made in the United Kingdom, it’s also not badly priced at $400. The British Royal Air Force cold weather parka is a little more expensive, but also a lot cooler looking (I have a similar parka from Kaptain Sunshine that I love).

They also have hand-knitted fisherman sweaters that were made in collaboration with Inverallan. You can find Inverallan knits elsewhere for cheaper, but these from Allevol are unique in that they’re made with indigo-dyed cotton yarns. Indigo, as many readers know, has a hard time binding onto fibers. So, when the indigo yarns abrade, they reveal their white core. It’s harder to fade an indigo top than jeans, but with the four-year-old sweater pictured above – which was worn by Okabe himself – you can see how the top of the cables and the elbows eventually gave way to a lighter color. I imagine a sweater like that would look terrific under a black leather jacket or, you know, an olive parka. You can find Allevol at their site and Clutch Cafe.

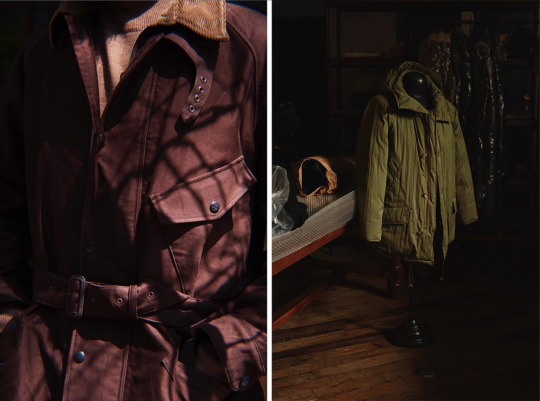

Speaking of black leather jackets, I’ve been really impressed by Fine Creek Leathers. The company is based in Tokyo, but offers heavy horsehide styles modeled after vintage American outerwear – cafe racers, double riders, and truckers. The garments aren’t cheap, but for fully Japanese-made leather outerwear – where the construction is done in Japan and the horsehides are tanned in Himeji – the prices are also not unreasonable. Most jackets are somewhere between $1,500 and $2,000, which is less than what many designer brands charge for jackets made in lower-cost countries.

Fine Creek Leathers is a great example of how a smart designer can transform classic workwear into something new, but also in a way without having a garment look as though it’s lost its roots. Whereas most brands take great pains to match their leather panels, Fine Creek purposefully mismatches different grains and finishes across seams. So, one panel may be made from a more grain-y leather, while the panel sitting next to it is smoother finished. The effect, which becomes more pronounced with wear, gives their jackets a more rugged, utilitarian feel.

I also love the detailing. Their double rider is available in two models: one with a belt and epaulets, like you’d find on a Schott Perfecto, and the other without. The ones without were actually originally made with a belt and epaulets, but Fine Creek cuts them off post-production. “They’re modeled after how certain vintage leathers were found” explains Kiya Babzani of Self Edge. “Years ago, bikers would cut these details off because they didn’t like how they flapped in the wind. We like our DRs without the belt or epaulets, so we had them make us the ‘cut off’ version.” In one of the photos above, you can see a small slither of leather where an epaulet used to be.

Fine Creek isn’t widely distributed outside of Japan, but you can find them at Pancho & Lefty and Self Edge. The second is hosting a trunk show tomorrow at their NYC store, where you can pre-order anything from Fine Creek’s coming fall/ winter 2019 catalog. The event is being held at Self Edge’s store at 157 Orchard Street, located in NYC’s Lower East Side. Doors will be open from noon until 7pm.

Sartoria Zizolfi isn’t really a brand, it’s a bespoke tailoring shop. It’s also a direct link to one of Naples’ greatest tailoring traditions. The shop’s owner and head cutter, Ciro Zizolfi, trained under Ciro Palermo, who in turn once worked as Vincenzo Attolini’s right hand man. During the early 20th century, there were two major tailors in Naples. The first was Angelo Blasi, who made his version of a British suit – a structured coat with slightly padded shoulders. The other was Vincenzo Attolini, who at the time was working as the head cutter at The London House (today known as Rubinacci).

Whereas Blasi made a Neapolitan version of a British suit, Attolini revolutionized Neapolitan tailoring entirely. He borrowed a soft-tailoring technique from Domenico Caraceni and used it to make lighter, deconstructed jackets that were better suited to Naples’ warmer clime. The lines were softer and curvier; the shoulders a touch extended; the chest built with just a touch of drape. Other tailors soon followed and that’s how we’ve come to associate the region with soft, casual tailoring ever since.

I first met Ciro Zizolfi about seven years ago. His workshop is about as modest as you can imagine – it’s located up some stairs and has no visible signage. It doesn’t look too different from any messy alterations shop you’d find in a major city, but the tailoring here is about the best I’ve seen anywhere. The buttonholes were beautifully hand-sewn, the topstitching carefully done; the felled seams neatly executed. But more than that was the style. Zizolfi’s jackets have all the hallmarks of true Neapolitan style with their sweeping quarters, natural shoulders, and soft lines, but they’re done in a way without looking like ten open browser tabs. So many tailors today try to copy this kind of look, but end up producing jackets that feel like a caricature of the real thing. You can see an example of one of Zizolfi’s jackets at Permanent Style. At the moment, Zizolfi only sees clients in London and Naples, but there are whispers that he may be visiting the United States sometime in the future. Here’s to hoping.

Take a stroll through any downtown center today and you’ll see the same eyewear frames everywhere. The styles are often slightly rounded, very hip, and made from molded acetate. The designs take after an American geek-chic style known as a P-3, which has been around since the mid-20th century. Allen Ginsberg wore something similar with a scruffy beard and faded flannel shirts. Luciano Barbera wears it with softly tailored Italian suits. Bruce Boyer once summed up the style nicely when he said it has a “hallmark simplicity in its shape, sentimental references to callow youth, and just a whiff of bookish charm.”

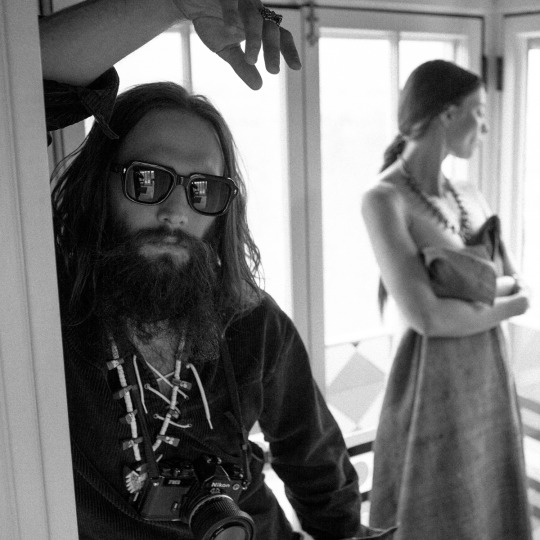

I love the P-3 as well, but in the last couple of years, I’ve grown to also appreciate bolder styles. Chief among them are those from Jacques Marie Mage, a brand that’s eye wateringly expensive, but at least offers tinted sunglasses that will shield your crying eyes from the public. The frames here are not for the meek, but they’re also not that hard to wear. I bought their Hopper collaboration sunglasses last year – which are modeled after something Dennis Hopper wore in Easy Rider – and find they go well with chore coats, Western workwear, and even sport coats. Their thick framed, slightly angular definitions are slightly sleazy in that Tom Ford-ish, 1970s way. They somehow manage to both draw attention to you while also making you feel like you’re hidden from view. Most frames will cost between $500 and $700 (trust me, I cried as well), but sometimes you can find them on sale for about $350 (trust me, I’m still crying like you). If you can stomach the prices, these frames are a joy to wear.

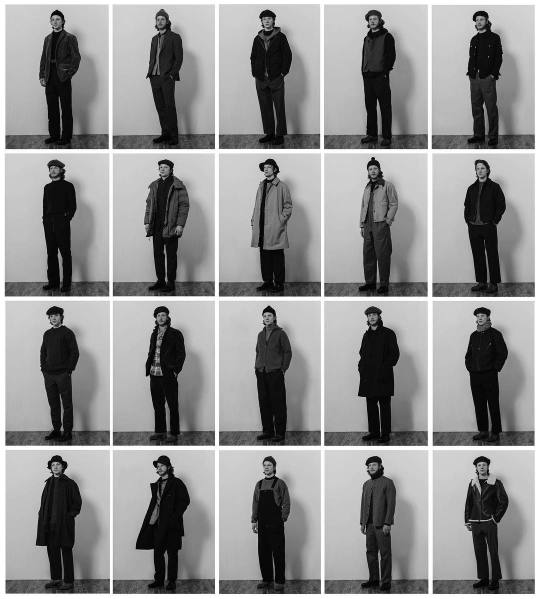

The concept isn’t entirely new (and frankly, neither is the brand). On the one hand, Phigvel is just another Japanese label making contemporary clothes inspired by classic military, work, and outdoor wear. On the other hand, they take greater liberties when interpreting how clothes should fit. The trousers here are often roomier, the shirts looser, and the jackets come with slightly shorter, rounded silhouettes.

I love the detailing they put into their outerwear. The map pockets have storm flaps to help keep out rain; the waists are adjustable with hidden drawstrings and buckled straps. The collars are always perfectly cut so they look good when popped from the back. These seem like the kind of clothes you can take as far as you want – all the way down the road to Repro Land or just off the path to Engineered Garments territory. Like Allevol above, they can also be worn with a simple pair of jeans and a chunky sweater, which allows them to be used in more conservative environments. Who couldn’t use a pair of comfy cut corduroys, a textured knit, or a military-styled raincoat? You can find Phigvel at Country Ltd, Coverchord, and their own site.