You’ve heard the phrase a million times: “You can have any color as long as it’s black.” In his autobiography My Life & Work, Henry Ford claimed he told his management team in 1909 that, going forward, his best-selling Model T would only be available in one color. But for the first few years of its production, from 1908 to 1913, it wasn’t available in black at all, but rather bullet gray, dark green, midnight blue, and fire engine red. The all-black change didn’t happen until 1914, with the outbreak of World War One. Ford switched to black because of the paint’s low cost, durability, and faster drying time. Paint choices were determined by the chemical industry, which at the time was affected by dye shortages and new nitrocellulose lacquer technologies. The decision had more to do with economics than style.

Cars back then were painted using a process called japanning, which today would be known as baked enamel. “It was first used in the mid-1800s for decorative items imported into America,” says Model T restorer Guy Zaninovich. “A piano has a shiny black surface that almost looks like plastic rather than paint because it’s done with the japanning process. It leaves a tough and durable surface.” Japanning also dries quickly, which was important to the efficiency-obsessed Ford. His plants produced as many as 300,000 cars per year, at a time when competing automakers had a combined production of about 280,000 cars, so shaving minutes off each car’s production time was critical. The catch? Japanning was only available in black. “If japanning worked in hot pink, all Model T’s would have been hot pink,” Zaninovich joked.

The history of the Model T is just one of the many strange stories of why certain things come in specific colors. Suits, for example, mainly come in navy and gray because, back in the Regency period, men wore navy coats with cream-colored breeches. Regency blue eventually gave way to Victorian black by the mid-19th century, but the norm for wearing contrasting trousers remained. The suit, as defined by a coat worn with matching trousers, wasn’t typical in London until the end of the 19th century. Until then, the suit was only worn for sport and leisure, mostly in the countrysides. No proper gentleman would ever wear it to town.

At some point, working-class Londoners adopted the suit as their everyday uniform, and they stuck with the traditional Regency-era blues and Victorian-era grays. In fact, what many consider to be the symbol of dignity and upper-class values was, at one point, considered the equivalent of beachwear and workwear. In 1892, Scottish socialist Kier Hardie — who later founded Britain’s Labor Party — was responsible for a cause célèbre when he showed up to his first day in Parliament wearing a suit. His clothing identified him as a member of the working class and someone who would advocate for working-class ideals. Hardie fought for a graduated income tax, free schooling, pensions, and women’s suffrage. The British press at the time lambasted him for wearing working-class attire — “a cloth cap in Parliament,” a scandalized newspaper said.

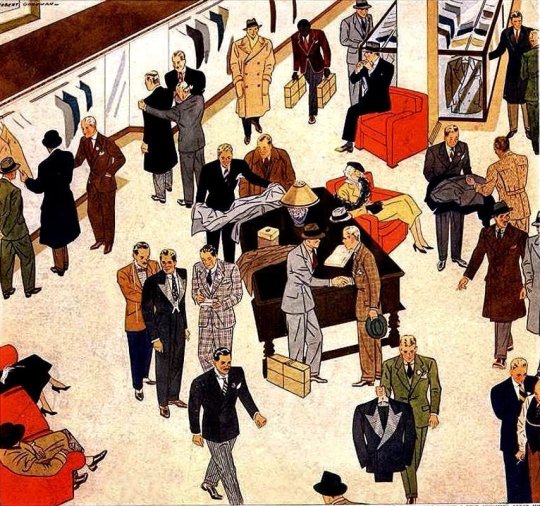

Despite their best efforts, fashion writers haven’t had much lasting success at getting men to wear suits in other colors. French blue is dandy; dusty tan is controversial. In 1928, an article in the trade publication Men’s Wear surveyed the men’s fashion at Palm Beach, then a center for glamorous resort style.

Palm Beach literally outdid itself this season, ‘fashion-ly’ speaking. Green was the newest note for jackets and was available in all the materials that men use for their jackets with the exception of linen. A light grayish green was seen on the very best dressed men, and the Lovat shades, in general, were those that the style leaders had accepted. These Lovats are mixtures of green with neutral grays, blues, tans, and browns. Pure green will not arrive as a color for men’s suits until the greenish shades of other colors have established themselves, which will take at least a year to develop significantly, and will require careful promotion of the authentic shades by men’s wear organizations.

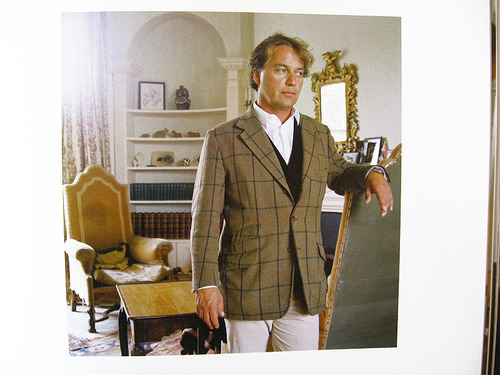

The author was a little early on the trend. Blue, medium gray, and gray-blue continued to dominate men’s suit sales for the first half of the 1930s. In 1935, a mere one-percent of sales included anything that could be called greenish, although the figure jumped up to an impressive 28 percent by 1939. Still, not long after, the color all but disappeared from men’s wardrobes. Sometimes you’ll see a greenish tweed sport coat, perhaps in a tightly woven herringbone or spongey Shetland, but it’s a challenge to get men to consider anything except blue, brown, and gray — the three colors anchored by tradition.

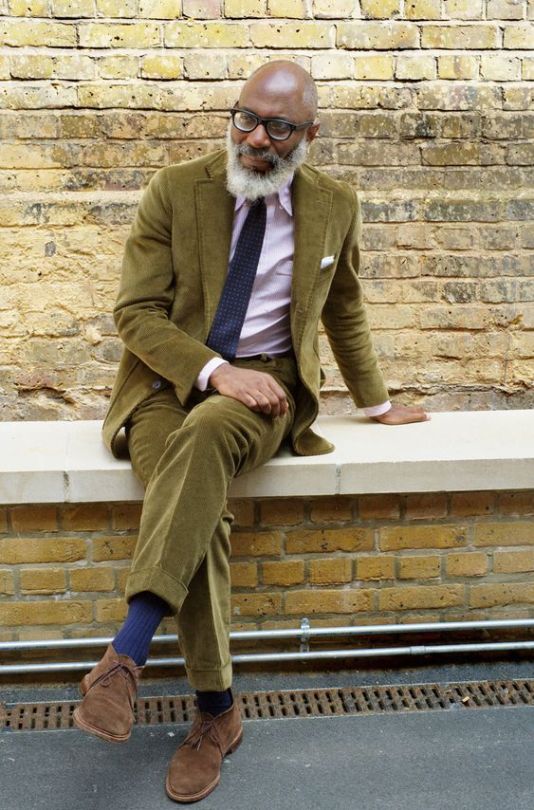

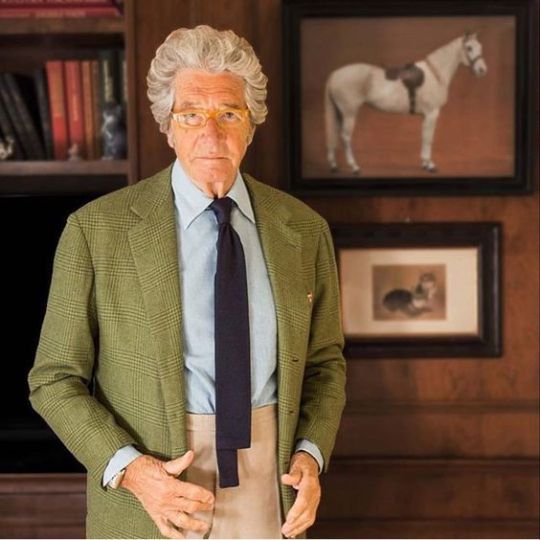

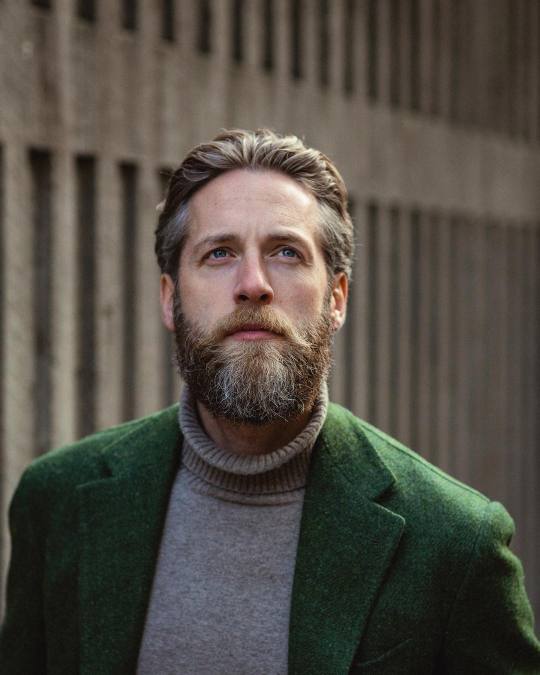

Still, I think green is excellent for tailoring. It goes well with navy sweaters and light blue shirts; khaki chinos, grey flannels, and mid-brown whipcords; brown lace-up shoes and black tassel loafers. As a color, it makes a sport coat or suit look younger and more contemporary. It makes a statement without resorting to wilder colors, patterns, or proportions. Its rustic nature allows it to pair naturally with blue jeans and denim shirts. Of course, not all greens are the same. There’s forest green all the way through to stone green, dull green to British racing green, Lovat to emerald. Ones with a yellow undertone, such as mossy olive, are usually easier to wear, although grass green can also be striking in the right context.

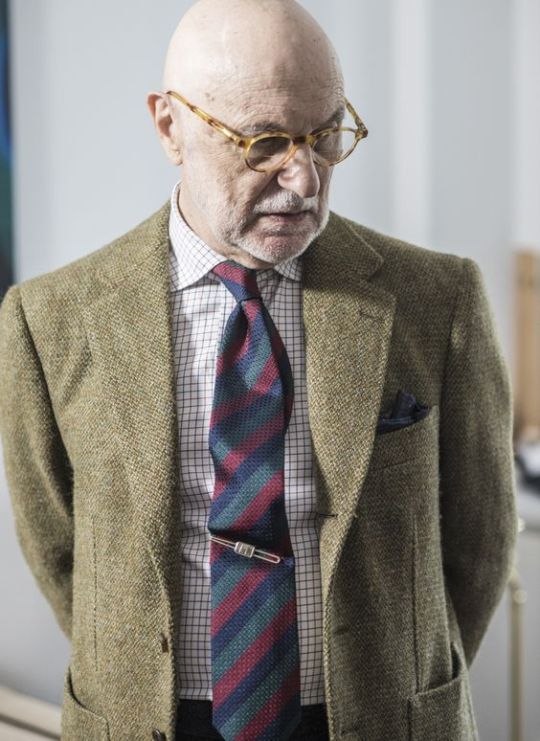

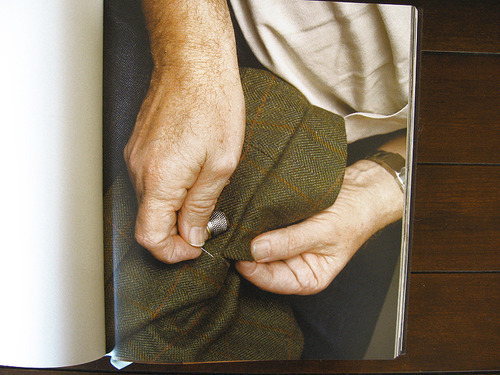

For fall and winter, olive checked sport coats are a natural choice. Some are described by the type of sheep that provided the wool (e.g., a Shetland or Cheviot tweed, which are named after Shetland and Cheviot sheep). Then there are regional tweeds, such as Harris and Donegal, both woven in the Harris and Donegal areas, respectively. Donegal is defined by its flecked coloring, but I find Harris can take any number of forms. And finally, there are sporting, game, and thornproof tweeds, which are often more robust and more densely woven than the spongy stuff.

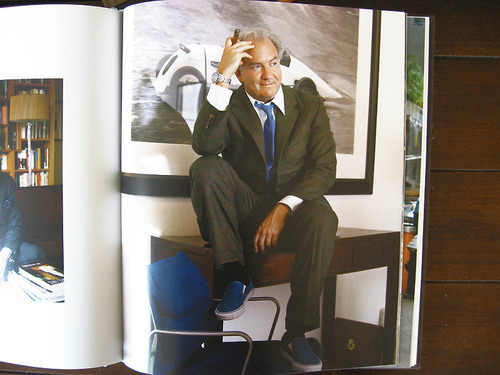

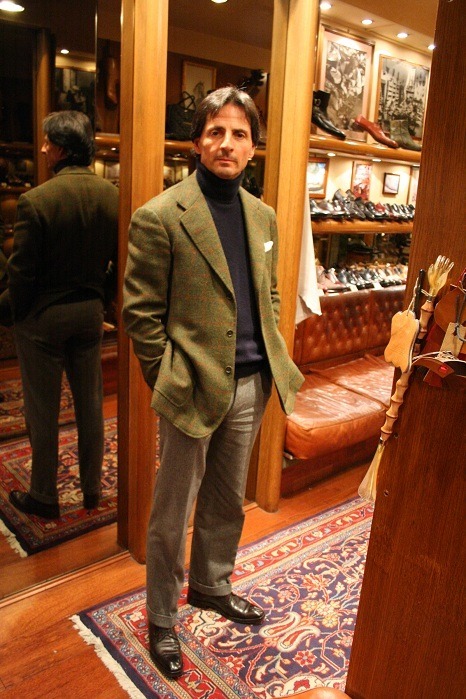

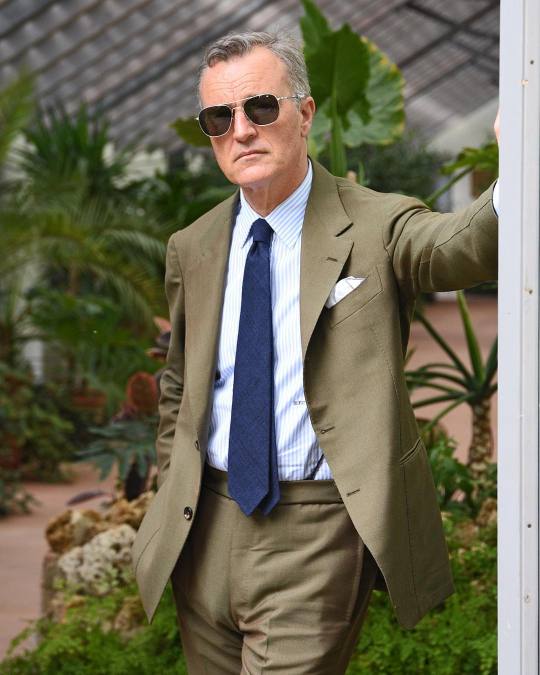

For shoulder seasons spring and fall, when the weather feels neither here nor there, try a mid-waled corduroy or lightweight covert cloth suit. Bruce Boyer, a documented green clothing appreciator, has a greenish taupe, covert cloth, double-breasted suit from A. Caraceni in Milan (famously once the tailor of Gianni Agnelli). Having ordered the suit while he happened to be in town, he was only available for two fittings, but the suit turned out pitch perfect – a 6×1 double breasted with bellied lapels, a soft shoulder line, and just a touch of drape in the chest. “Some of my friends tell me I look better in gray, but I happen to like greens and browns, and it seems so easy to mix those earthy colors with more vibrant ones like blues and oranges and yellows in the accessories,” he once said at Put This On of the green sport coat outfit above. “And of course you can always get new friends, but a good sports jacket can last forever.”

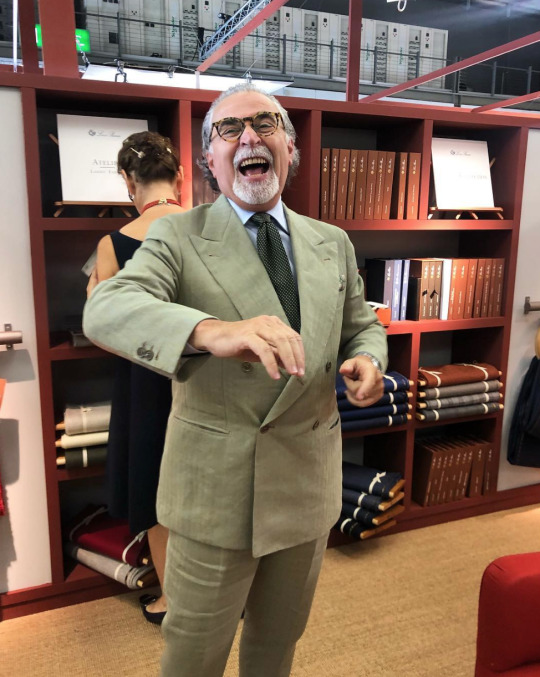

On the warmer side of the year, there are slubby linens, heavy cottons, and textured wool-blends. At a recent Sartoria Solito trunk show in San Francisco, I was thumbing through some swatch books and almost added an olive cotton-cashmere suit to my order. Luigi, who represents his family’s company at these overseas shows, noted that his father often wears an olive cotton-cashmere suit to work. “It can be casual, but still be look very sharp,” he told me. Hard to argue with how the older Solito looks on Instagram.

Unfortunately, as the market for quality tailoring has shrunk, it’s hard to find anything but your basic navy and gray worsteds. This season, there are tonal olive seersucker suits from Eidos and Drake’s, glen-checked Fox sport coats from Sartoria Formosa, and muted green, linen sport coats at The Armoury. This VBC covert cloth suit looks particularly good. Mr. Porter also has a wool-stretch blend suit from P. Johnson. I find their ultra-soft tailoring fits some men better than others, although I appreciate that their jackets are longer than those from similarly soft brands such as Boglioli. Tailored clothes mainly come in blues, browns, and grays, but much like the modern counterparts to Ford’s black Model T, other hues can also be worth your while.