Fashion is often criticized for its creative destruction. Trends are constantly coming and going; new brands are always emerging. What some see as a pointless field, I see as a subject where there’s always something fresh, something engaging, something different to talk about. For the past few years, I’ve been doing annual roundups about new brands I’m watching. To be sure, not all of them are actually new — some have been around for a while. But they’re new to me and, hopefully, you. This year, I have so many brands on my list that I decided to break this post into two parts. The first part was published two weeks ago. This is part two.

HUSBANDS

The lines on Husbands’ tailoring are as strong and well-defined as the facial features of the company’s founder, Nicolas Gabard. Gabard is a strikingly handsome Frenchman who wears suits and sport coats with Cuban-heeled side-zip boots. In a previous life, he worked as a lawyer to please his father but soon found himself rummaging through flea markets on weekends in search of vintage clothes. Now he has his own clothing label, Husbands, which is headquartered in the affluent 2nd arrondissement of Paris, a stone’s throw from Palais-Royal. Husbands’ tailoring is youthful, sleek, and above everything else, sexy. Their suits have defined shoulders, wide lapels, and a dropped buttoning point, giving the wearer strong, architectural lines. Yet, there’s also a natural elegance to everything, as the full-bodied jackets have leafy skirts that sway like fronds. The high-waisted pants have long, slightly flared legs shaped like ringing bells, hinting at movement even when the wearer is standing still. “Husbands’ style is about getting off the beaten track — risk-taking,” founder Nicolas Gabard tells me. “In that respect, the Husbands’ style borrows its boldness from the Italians, which is then counterbalanced by the rigor of the English line. Husbands’ style is therefore resolutely French: at the crossroads of these two territories.”

Husbands’ tailoring challenges everything that has been said about menswear in the last ten years. Rather than short jackets, they make their coats long, showing how a full skirt can slim the hips and make the wearer look trim. And instead of soft, deconstructed jackets that fit like cardigans, Husbands’ liquid sleekness comes from the smart use of horsehair, padding, and canvas. Even with a padded shoulder, these jackets look relatively casual, partly because of how they express a youthful sense of cool. Husbands’ suits are chic and sexy, draw from the right periods (often the ’70s), and show how tailoring isn’t just for corporate boardrooms.

“Even before COVID-19, we realized that professional and social obligations for clothing are disappearing,” Gabard elaborates. “We had to explain the relevance of these clothes to people who were not yet customers of tailoring. In other words, we had to turn this once-compulsory garment into something that’s about choice and pleasure. That said, we have always had lawyers and bankers as clients, but they also want to experience the joy of dressing themselves. Many men are ready to experience the excitement of a classic wardrobe because it’s a great field for expression. By saying who you are through your clothes, it’s possible to wear tailoring in a cool, non-corporate way. To do this, you have to play with the details: the collar, the lapel, the color, the width of a stripe, the cut of the trousers, etc. You can personalize a suit by wearing it with things that resonate with who you are, such as sneakers or a boy scout shirt.”

I love that Gabard has a cultural view of style. He understands that a good outfit is not about abstracted aesthetics, but how to write a sentence using clothes. In the last fifteen years, the growth of what I’ve described as “review culture” has made many men focus on just the technical aspects of tailoring. To be sure, Husbands’ clothes tick all the right checkboxes for quality. These coats are fully canvassed, made in Italy, and feature handmade details such as Milanese buttonholes. But they’re also emotive and culturally legible. I’m convinced this comes from Gabard’s eclectic interests. In a Financial Times profile published last year, Gabard talks about his love for the suits Tommy Nutter made for The Beatles, the integrity of Dries Van Noten’s collections, and the costumes in Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now. “You read Proust, and you love ankle boots. You listen to The Smiths, and you love Morrissey’s clothes. You see Alain Delon in Le Samouraï, and you love trench coats,” he says. This appreciation for the emotive and cultural dimensions of tailoring turns the template for conservative business dress into something expressive and personal (what I call “dressing for a vibe”).

PETRU & CLAYMOOR

Ten years ago, if you wanted a well-made shoe without spending your life’s savings, your options were mostly confined to Allen Edmonds’ factory seconds and a handful of hard-to-find European labels. Since then, the lower end of the price spectrum has dramatically filled out. You can now buy some beautifully designed, well-made shoes for a couple of hundred bucks from relatively new brands such as Meermin, Lof & Tung, Grant Stone, TLB Mallorca, Morjas, Beckett Simonon, and Jay Butler (the last being a sponsor on this site). All of these companies offer exceptional value.

The upper end of the price market has not fared as well. Foster & Sons’ reconfigured ready-to-wear line, which they launched shortly after purchasing a shoe factory, closed almost as soon as it debuted. One of the problems is that it’s hard for consumers to see value in machine-made, Goodyear welted $1,500 shoes, particularly when hand-welted shoes nowadays can be had for much less. New labels also don’t have the heritage of established brands such as Edward Green and John Lobb.

Petru & Claymoor, a sponsor on this site, is an exception. At their workshop in Brașov, Romania, they’re creating custom, handmade shoes and selling them for the price of what high-end brands charge for machine-made ready-to-wear. People obsessive about footwear are probably already familiar with the process: these are hand-welted, hand-lasted, and feature a hand-sewn sole. Instead of using the more common Celastic (basically plastic), the company uses leather stiffeners, which are easier to repair if the stiffener ever breaks down. “We wanted to be loyal to the idea of a traditional shoe, so we turned our backs on machines and mechanization in general,” says co-founder Mircea Cioponea, who used to write about shoes under the name Claymoor (hence the second half of the company’s name; the first half being reflective of the other co-founder, Petru Coca). “We use only traditional materials: leather, cork, linen thread, wax, and ecological dye. We have no plastic components or industrial cork paste. The only machine used is the sewing machine for the uppers.”

In some ways, the proposition isn’t totally new. Vass offers customizable hand-welted footwear for about $750. Petru & Claymoor costs about double that amount — roughly $1,650 for calfskin shoes and $2,200 for boots — but they offer something closer to the bespoke process. They have five standard lasts, one of which is specific for women and another for clients in Asia. These are used to make fitting shoes (a test shoe made from scrap leather), which are then sent to the client to assess the fit. If necessary, they adjust the standard last to create a personalized last, which is then used to create the final pair of shoes. Customers can order shoes through Petru & Claymoor’s trunk shows or their showroom in Bucharest, or do remote fittings through the internet.

Some readers will make the comparison to Saint Crispin’s. For me, I’ve only ever liked one StC last, the Classic. Petru & Claymoor has a wider range of tasteful, conservative lasts, and they don’t use wooden pegs at the waist. Both companies seem like a bridge between high-end ready-to-wear and bespoke, giving you some of the construction techniques and customization of bespoke without paying more than you would at Edward Green. It’s an interesting proposition at this end of the market, chipping away at the reasons one might spend over $1,000 for factory-made footwear.

LABOUR UNION

In the last few years, fashion prices have soared. Over at Mr. Porter, you can find shimmering sequined sweatpants selling for nearly $15,000 — the cost of a Nissan Versa, or two vacations for a family of four. I’ve tried to include some affordable brands in this year’s list to make these posts useful for a wider range of budgets. In my last post, I wrote about how South Korean labels are producing tailored clothing and rugged workwear at surprisingly affordable prices. The same thing is happening in China. As menswear culture spreads through the internet, young people in different parts of the world are starting their own companies, producing clothes that you used to only see come out of Japan, Western Europe, and the United States.

The challenge is figuring out how to buy something. Many Chinese brand owners don’t speak English, and Chinese shopping platforms such as Taobao are impenetrable to outsiders. The Remains makes interesting vintage-styled workwear, but I can’t figure out how to purchase anything. Bob Dong, a Chinese company with a tongue-in-cheek name that parodies American machismo, is available on eBay. But when people ask where you bought your clothes, you then have to say “Bob Dong.”

Labour Union is one of the few Chinese brands with an easy-to-use English website. They’re like an affordable version of RRL, producing ranchwear, rockabilly, and things that American GIs wore while stationed in the Pacific during the 1940s through ’60s. The company sells riveted ranch jackets made from 15 oz red-line selvedge denim ($173), drizzle-proof deck smocks ($173), goose-down padded mountain parkas ($342), and roomy raglan overcoats shaped like A-line cowbells ($386).

Of course, you can expect some compromises at this price point. Labour Union’s Fair Isle sweaters are made from an 80/20 mix of wool and acrylic, but cost about the same as what you’d pay for an authentic Scottish Shetland Fair Isle made from pure Jamieson’s wool. Some overcoats are listed as 80 percent wool and nothing else (what’s the other 20 percent?). The Aloha shirts are mysteriously 50/50 Lyocell-polyester even though Lyocell is not terribly expensive. Still, a friend of mine bought this fly fishing jacket, which is modeled after the Ideal jacket I wrote about a few months ago, and he has nothing but good things to say about it. Do your homework before shopping.

THE WORK

When British economist Alfred Marshall looked out of his window in the late 19th century, he saw a country full of cottage industries and industrial clusters. In the Scottish Border towns up north, thousands of spinners, weavers, and knitters were making robust tweeds and soft cashmere. Further south was Manchester, where steam-powered mills produced so much of the world’s cotton, the city was nicknamed Cottonopolis. In the East End district of London known as Spitalfields, the descendants of French Protestant refugees and Irish immigrants were toiling over looms to make some of the world’s most beautiful silks. Alfred wrote about these clusters in his 1890 book, Principles of Economics, which has since become a standard text for econ students and the foundation for how many people think about regional growth. The short of it: when cooperative, interconnected firms are located near each other, they can share knowledge, labor, and other types of resources.

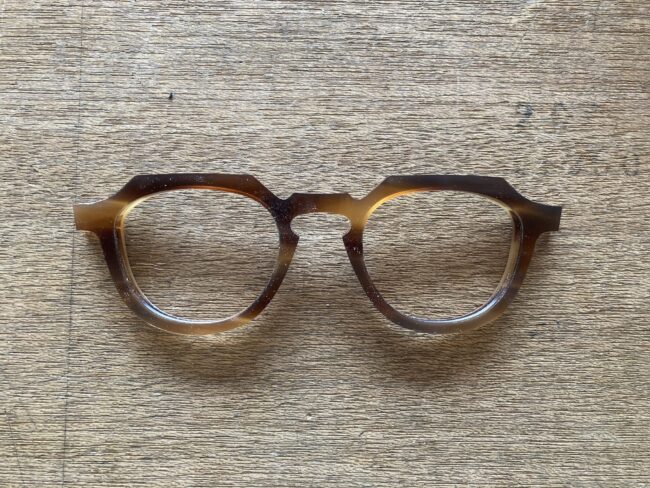

On the western coast of Japan, there are two such clusters — one in the capital city of Fukui and the other in nearby Sabae. At the turn of the 20th century, Sabae was a poor farming village disconnected from the rest of Japan until a politician named Masunaga Gozaemon built eyewear-making guilds with the help of skilled craftspeople he brought in from Osaka and Tokyo. By 1935, Fukui and Sabae were producing the bulk of Japan’s eyewear. From the ’50s through ’70s — a period dubbed the Japanese economic miracle — these twin cities made eyewear that rivaled the best of what came out of Europe. Today, when you see brands such as Jacques Marie Mage, Garrett Leight, and Eyevan stamp the inside of their eyewear with “Made in Japan,” it’s likely those frames came from one of these two cities.

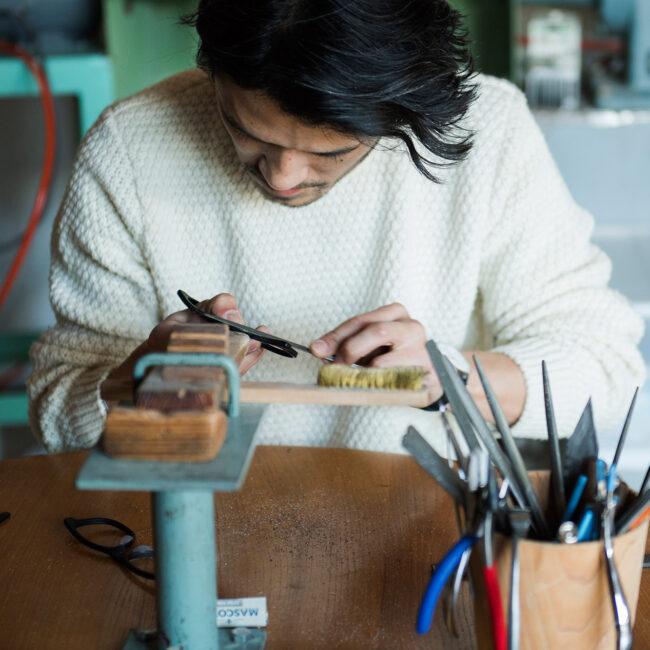

In a small, one-story building located on one of the quieter streets in Sabae, Keisuke Ueki is creating eyewear using Sakazaki machines stationed under fluorescent tube lights. He’s the brother of Noriyuki Ueki, the bespoke tailor behind Sartoria Ciccio. Keisuke has an enviable windswept hairstyle, like sea-salt-encrusted beach hair artfully suspended in perfect form, which hangs just above his eyebrows as he labors over his workstation. He learned his craft by working for one of the local Sabae eyewear-making firms for over ten years. A few years ago, Keisuke launched his own eyewear company, which he simply named The Work.

The Work outsources their frame cutting and lens production, but Keisuke does all the assembling and finishing himself, which he estimates is about 80 percent of the production process. “In Japan, there is a saying, ‘温故知新’ (onkochishin). It means ‘studying the old to make something new,’” he explains to me. “My frames are inspired by vintage designs but done in a new style. I want to create designs that no one will get tired of.” The Work’s spirit for timeless, but recognizable design has resonated throughout Japan’s craft-based menswear industry, as you see his frames on notable figures such as Kenji Kaga and Yohei Fukuda.

At the moment, the company only has a few styles, including a rounded design with a keyhole bridge and something reminiscent of Steve McQueen’s Persols. Since everything is produced through a small-batch process, The Work can also create MTO and bespoke glasses. At the moment, they’re making an exclusive style for Atelier BRIO Pechino. Modeled after a mid-century French Panto style, these frames have scooped corners, a flattened top, and a broad base, giving the wearer an artful sensibility (a prototype of BRIO’s frames are pictured above). “When you produce eyewear frames by hand, you can express fine details that aren’t possible in mass production,” says Keisuke. “This is what makes handmade eyewear so beautiful.”

X OF PENTACLES

It’s an industry secret that many accessories designers don’t actually design. Instead, they’re more like Indiana Jones in search of a lost grail. They visit silk printers in Macclesfield or Como, where they rummage through archival fabric books, looking for prints and patterns to reproduce. They may change some color here or there, but it’s ultimately the same thing. After the fabrics are reprinted, the materials are turned into three-fold ties, scarves, and other accessories.

Marcel Ames designs. His company, X of Pentacles (pronounced “Ten of Pentacles”), sells everything from custom shirts to suits. However, their core strength is in wool-silk scarves and pure silk ties, which Ames designs in Richmond, Virginia, and then has produced in Italy. Ames got started in the menswear trade about ten years ago when he was fresh out of college and began to work for Saks Fifth Avenue and Paul Stuart. Wanting to find a more stable career, Ames became a mental health clinician and later a police recruit at the Richmond police academy. But in November 2014, his law enforcement career plans were derailed when he suffered a concussion during police training. Shortly after, he lost his father and then his home. Ames is all too familiar with the fragility of life’s plans, his own life reflected in one of Shakespeare’s most famous lines, “to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” If the arrow of misfortune doesn’t kill you, it can be so deeply embedded in your body, you die later from the pain of infection. “I lost my career, my dad, and my home,” he says. “For quite some time, I felt like I lost my mind.”

While couch-surfing during that challenging year, Ames found solace in sketching. He went back to the thing he loved — menswear. Ames sketched out patterns for ties and scarves, as well as the shirt collars he wanted to hold them. Two years after losing everything dear to him, he launched his company, X of Pentacles, named after the tarot card for stability and success. I love that Ames is a self-taught designer who learned how to illustrate by using a “cracked” graphic design program on his old college laptop. He’s creating something new and isn’t just rehashing the same David Evans archival prints you see everywhere. “I knew that if I just recycled archived prints, I would be no different from everyone else,” he tells me. “The best way I can describe our aesthetic is if Hermes, Gianni Agnelli, Vincent Price, and Griselda (the rap group) conceived a child. Decadent, mysterious, tasteful, and a little gritty.”

My favorite pieces are the dusty colored scarves at No Man Walks Alone (a sponsor on this site). X of Pentacles often highlights cultures from around the world, including non-European ones that typically get overlooked in menswear. The Khatt scarves feature intertwining, flowing lines typical of Arabic or Moorish decorations, while the First American scarves pay homage to richly woven Native American tapestries in the American southwest. “I’ve always been fascinated with Arabic calligraphic art and architecture,” Ames says of the collection. “Traditional script is made with a bamboo reed and India ink. I used a similar method to create a tessellation of patterns — like a mosaic — but subbed out the bamboo reed for balsa wood. The result is like having a piece of Morocco around your neck.”

THE BRUT COLLECTION

Brut is hardly a new brand, as this year marks its tenth anniversary. Paul Ben Chemhoun started the company as an online business in 2012 when he was still a student. After moving to the French capital and finding that his vintage clothing collection was beginning to crowd out his small apartment, he opened a showroom in what he describes as an “old cave in central Paris.” Initially, the company’s showroom was only opened during Paris Fashion Week. French designers were uninterested in these old rags, but the clothes were coveted by foreigners, who soon came in packs of eight, rummaging through Chemhoun’s ancient treasures between fashion week appointments.

“Vintage French clothing doesn’t interest French people much,” Chemhoun once told Heddels. “When I started, 80 percent of the stock ended up being thrown away, so in a way, we were running against time. The lack of interest in France comes from the negative connotations of the French chore jacket (or bleu de travail). Historically, a factory worker would never wear his chore jacket outside of work. He’d always leave it at the ‘room of the hanged men’ (salle des pendus), which was this room where the workers’ clothes would be kept inside huge buckets, each lifted under the ceiling by a rope. Farmers and woodworkers in the countryside would walk outside with their chore jacket, but factory workers in the city would always leave them in the factory.”

Chemhoun’s commitment to vintage French workwear eventually paid off, and today, Brut (French for “raw”) is not only a wildly popular Instagram account but also a destination shop for vintage aficionados visiting Paris. Brut is where fashion designers go for inspiration, and where costume designers shop to pick up pieces for new projects. I wanted to mention them in this year’s list because they’ve been doing an in-house line, which they’ve simply named The Brut Collection.

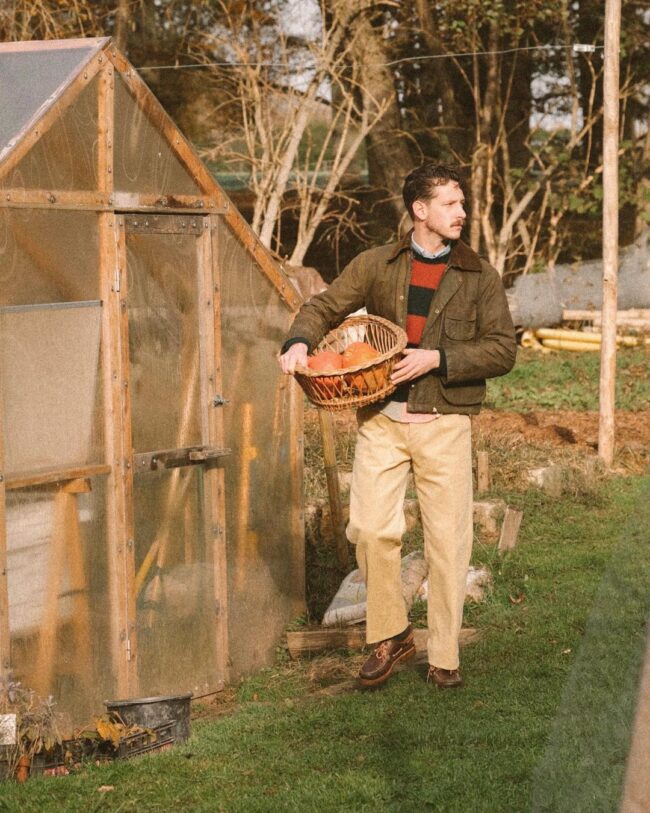

Pieces from The Brut Collection are not inexpensive, but they’re reasonably priced compared to the rest of the fashion market. The clothes are typically made in France using a small-batch process, sometimes at Brut’s workshop and using vintage upcycled fabrics. The Eddie Bauer-inspired liner vest and reconfigured French officer trousers retail for about $185. They have patchwork “fun shirts” inspired by Brooks Brothers ($160), hooded mountain parkas made from cold-weather US Army sleeping bags ($485), bubble-shaped fishing jackets ($200), and reworked Barbour Spey fishing jackets (a hard-to-find collector’s model, sold at Brut for $465). Shrewd shoppers may be able to find similar products elsewhere for cheaper. These French-made USN deck sweaters cost about $250, but you can find vintage-styled British knits from Highland 2000 for half the price (and even cheaper at the British resale shop Marrkt). Still, the styling at Brut’s Instagram account is so compelling, and the great majority of their products are unique, their in-house collection is something worth paying attention to. You’re getting boutique clothes made by people with a keen eye for vintage clothing, but everything is sold for a fraction of what you’d pay in the designer world.