In an interview with The Telegraph, Patrick Grant of Norton & Sons once described fashion as being an “ever-moving feast.” I find that the quick-paced nature of fashion — where things are constantly being created and destroyed — makes the field endlessly interesting. There’s always something new, something different, something to talk about. For the past few years, I’ve been doing annual roundups on new brands I find to be interesting. To be sure, not all of them are new — many have been around for years — but they’re new to me. This year, there are so many brands on the list, I’m splitting the post into two parts. Here’s part one, with part two coming later this week.

NORLHA

With a camera in her hand and a translator by her side, Dechen Yeshi arrived at the Amdo region of the Tibetan plateau in 2004. She came partly to explore her family’s history on her father’s side, a Tibetan academic who once served as a Minister to His Holiness the Dalai Lama. She also came at the behest of her mother, Kim Yeshi, a French-American anthropologist who co-founded the Norbulingka Institute, a Tibetan cultural center based near Dharmsala, India. Kim has always been fascinated by textiles, and long believed that yak wool could be a source of income for Tibetan families. So she sent her daughter Deschen to investigate.

While in Amdo, Deschen fell in love with the region — and yak wool. Three short years after her arrival, she and her mother founded Norlha, the Tibetan plateau’s first yak wool atelier. In many ways, Norlha is like the Inis Meáin of Tibet. Both were co-founded by academics (Kim is an anthropologist, whereas Inis Meáin founder Tarlach de Blácam originally came to the Aran Islands to study Irish). Both founders also have familial ties to the region and now live where their workshops are based. And like Inis Meáin, Norlha relies on its region’s deep heritage to make its luxury goods. Just as Inis Meáin makes upgraded versions of basic Aran sweaters, Norlha is two or three steps up from the scarves, bags, and home furnishings you can find in many Tibetan shops.

In the past, Tibetans who owned too few animals, or wished to have different opportunities, had to move to the city for work. Norlha began as a way to create economic opportunities for Tibetans out in the grasslands. Over the last 13 years, the company has grown from 30 to 130 employees, all former nomads or members of nomadic families. Ruby Yang, an Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker who visited the atelier, says Norhla has been a way to move the local economy past agriculture. “Some of the families, especially women, can [now] have a stable job,” she told The New York Times. “It’s very difficult for women to find a job outside of the village. They have to travel so far. In the village, they now have a job that makes decent money. And it also helps the men. Now the nomads are changing. The younger people might not want to be a nomad anymore. If one member of the family can have a stable income while another person decides to become a nomad, the family can be better off. […] The products they make are absolutely beautiful. They are taking the traditional skills they have and marketing it to the outside world. Few people know nomads can make such beautiful products. People don’t know they have been doing it for centuries.”

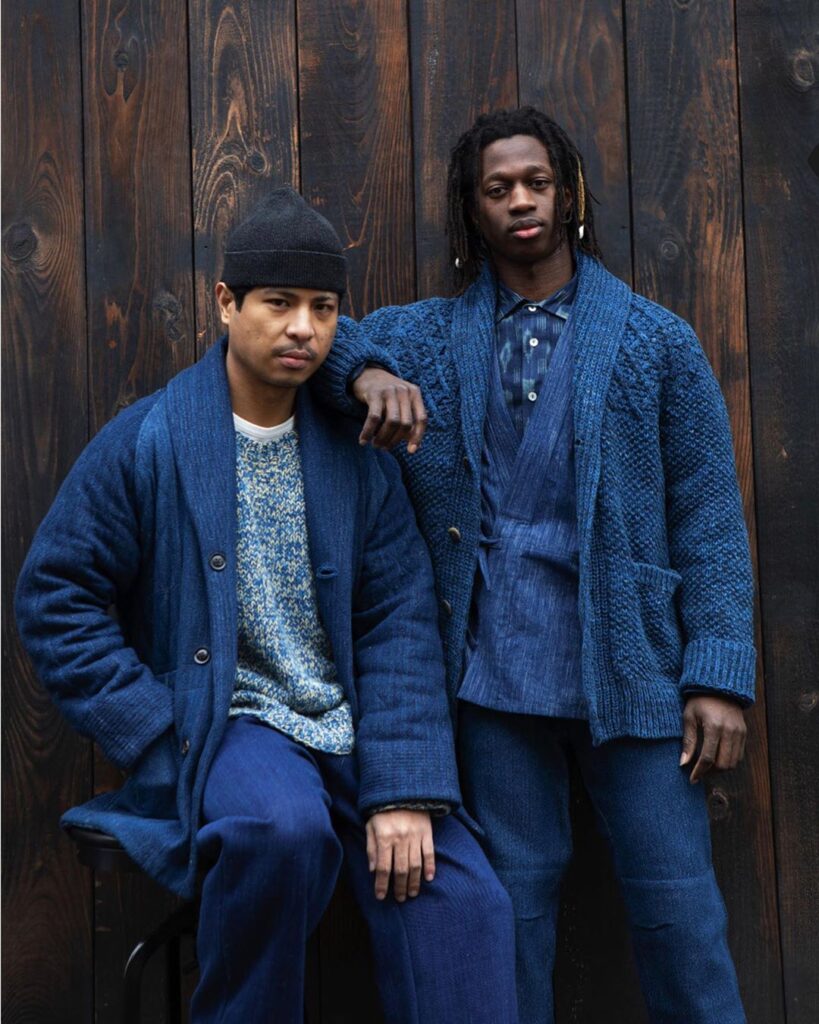

Norhla’s products are made from khullu, the precious undercoat layer that insulates yaks from the Tibetan plateau’s harsh winters. It’s a soft, downy, almost slippery fiber. Like cashmere, it has to be carefully picked, not shorn. Once the material is gathered, it’s handspun into yarn, handwoven on a shuttle loom, and then made into luxury goods. The company makes a range of charming home furnishings, such as felted blankets, plush cushions, and carpeted rugs. In the menswear section, you can find khullu-blend topcoats, slubby cotton trousers, and indigo-dyed chore coats. I love the idea of wearing these indigo trousers at home with a long-sleeved tee and some Japanese house slippers. The company also has a wide selection of chic scarves that would make for a wonderful Christmas gift. Even the simple, solid-colored scarves have a lot of variegation.

JUNIOR’S

It takes a bit of optimism — or perhaps chutzpah — to start a tailored clothing company in 2020. But Glenn Au, founder of Junior’s, always dreamed of one day running his own operation. He got his start in the trad trade eight years ago, when he went to work at O’Connell’s in his hometown of Buffalo, New York. Later, Au moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where he worked for the haberdashery H. Stockton. In February of this year, he set up his own shop, Junior’s. “I feel like I’ve been hearing about the ‘downfall’ of tailoring my entire career,” he tells me. “Part of it is true. But the best men’s clothiers are surviving for a couple of reasons. One is that they’ve developed intimate relationships with clients and are providing quality customer service. The other is that they don’t chase trends, and Junior’s won’t either. At the foundation of Junior’s, we like our clothing to have longevity — to look good now and even better in the years to come.”

Junior’s specializes in classic American dress, including made-to-measure tailoring, sportswear, and accessories. Their house cut is a natural shoulder coat with a 3-roll-2 front, open patch pockets, side vents, and a half-lined interior. Ivy purists can also request a “full Ivy” coat, with a center hook vent, undarted front, and lapped seams. For made-to-measure tailoring produced at a historic American clothing factory based on the East Coast, the clothes are surprisingly affordable. Fully canvassed suits and sport coats start at $1,025 and $795, respectively. Trousers start at $315; shirts begin at $165.

While I don’t have anything from Junior’s, I’m intrigued by the value proposition given Au’s fitting experience and keen eye for fabrics. His Instagram is peppered with images of summer worsted checks, autumnal Harris Tweeds, and creamy wool-blends. Made-to-measure appointments can only be held in-person (perhaps a bit more difficult now because of the pandemic). But those who wish to shop online can find a range of Scottish Shetland sweaters, cotton canvas trousers, rugby pullovers, and leather belts on Junior’s website. Au tells me he plans to put up some ancient madder and repp stripe neckwear from England soon, too.

INDI KIDS

There was a time, not long ago, when companies went to great lengths to hide their production information if they used labor in a low-cost country. Today, brands such as 18 East, 100 Hands, and 11.11 not only make their clothes in India, they sell themselves on this fact. A few weeks ago, I asked Agyesh Madan, co-founder of Stoffa and recent 11.11 collaborator, what he thinks is behind this shift. “Ten years ago, companies were just starting to pull back the curtain and show how things were made,” he says. “It was no longer enough to say ‘made in Italy’ or ‘made by hand.’ I think this eventually gave people a certain vocabulary. When people have the vocabulary to talk about clothing production, you can show them how things are made in other parts of the world, and explain why the quality is good.”

In India, companies can hire skilled artisans for labor-intensive processes that might otherwise not be possible in other parts of the world. Spread throughout the country are artisan collectives, often based in villages, which specialize in just one or two parts of the clothing production process. In West Bengal, there are people who hand-spin yarn and hand-weave fabric. Over in Puducherry, fabrics are hand-dyed in natural indigo. Perhaps the most famous are those collectives based in Bagru, where you can find chippas, a caste of printers that combine the skills of an artist, a toolmaker, and a carpenter. Day after day, they stamp lengths of cotton fabric by hand, using hand-carved wooden blocks and thickened mordants. It’s believed that fabric printing originated in China about 4,500 years ago, but hand block printing reached its highest visual expression on the Indian subcontinent. For years now, Dries Van Noten and Hermes have relied on Indian block printers to help make their clothes and accessories.

Indi Kids is among the many menswear-related lines operating in India (although the brand itself is based in New York City). The company started three years ago with a small line of children’s clothing. Today, they’ve expanded into men’s and womenswear. The garments are made through various labor-intensive processes — materials are woven on handlooms using handspun yarn, then sometimes Shibori dyed or hand embroidered. Some of the pieces are basic enough to find a home in almost any closet, such as their gauzy popovers and deep indigo plaid shirts. I love the idea of wearing this camp collar shirt in my backyard with Joyce’s rayon-blend shorts and Chamula’s leather huaraches. The clothes are a little crunchy in the free-spirited way that I think has taken over some parts of menswear, but they also go well with summer basics and are refreshingly affordable given the work involved.

HOSOÏ PARIS

When the founders of Louis Vuitton and Gucci first set up shop in the 19th and 20th centuries, luxury was based on the idea that you could pay top dollar to get an exceptional product. Today, that’s no longer the case. Over the last forty years, corporate profiteers have bought up and hollowed out some of the most famous luxury names. LVMH, most famously, now owns everything from Loro Piana to Guerlain to Moët. As many of these companies have gone corporate, they’ve relentlessly focused on the bottom line and quality has disappeared. Designs have become more formulaic, cheaper materials are used, and skilled artisans have been replaced with automated machines. Yet, many continue to trade on the idea of craftsmanship. In the spring of 2010, the U.K.’s Advertising Standards Authority banned two Louis Vuitton print advertisements because they wrongly suggested the company’s products were handmade. In fact, the company’s bags are machine-sewn. The lightweight bags aren’t even made from leather, but rather a cotton canvas coated with plastic.

If you want that old-world luxury today, you have to turn to lesser-known names, often small workshops run by artisans. In the Faubourg Saint-Antoine district of Paris, for example, you can find a building that houses various creative operations, including lithographers, sculptors, and people who create ornamental designs for fanciful interiors. Among them is Hosoï Paris, a newly set-up leather goods workshop run by a Japanese artisan named Satoru Hosoi.

Hosoi started his company just last year, after working twenty years in the luxury leather goods trade — ten of those as a craftsperson at Hermes, and another five as a designer at Moynat. At his own company, he makes beautiful, fully handmade leather bags and folios. The items are saddle-stitched, which means two needles are passed through the same hole by hand, creating a more secure seam. This is the same technique used to sew moccasins or construct handmade luggage, and you can see it demonstrated in this Hermes video.

The designs are downright dreamy. The Tolbaic carryall and Either weekender look like they’d be perfect with a tan gabardine suit. The bright green Piroette folio with a turnkey lock seems like an accessory stolen from the set of the 2001 film Amélie. I also love the details: the gold printed numbers and the thoughtful, handsewn feet, which keep the bottom of your bag from getting dirty. Given that these are fully hand-sewn, I imagine the prices are eye-wateringly expensive. However, the products inspire.

WYTHE

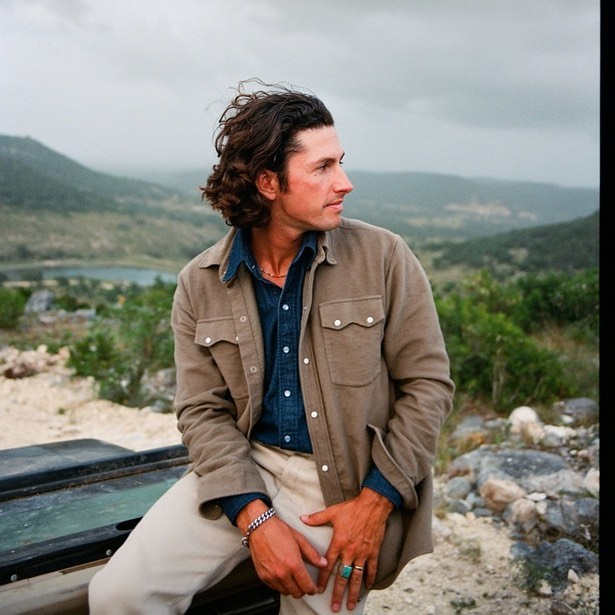

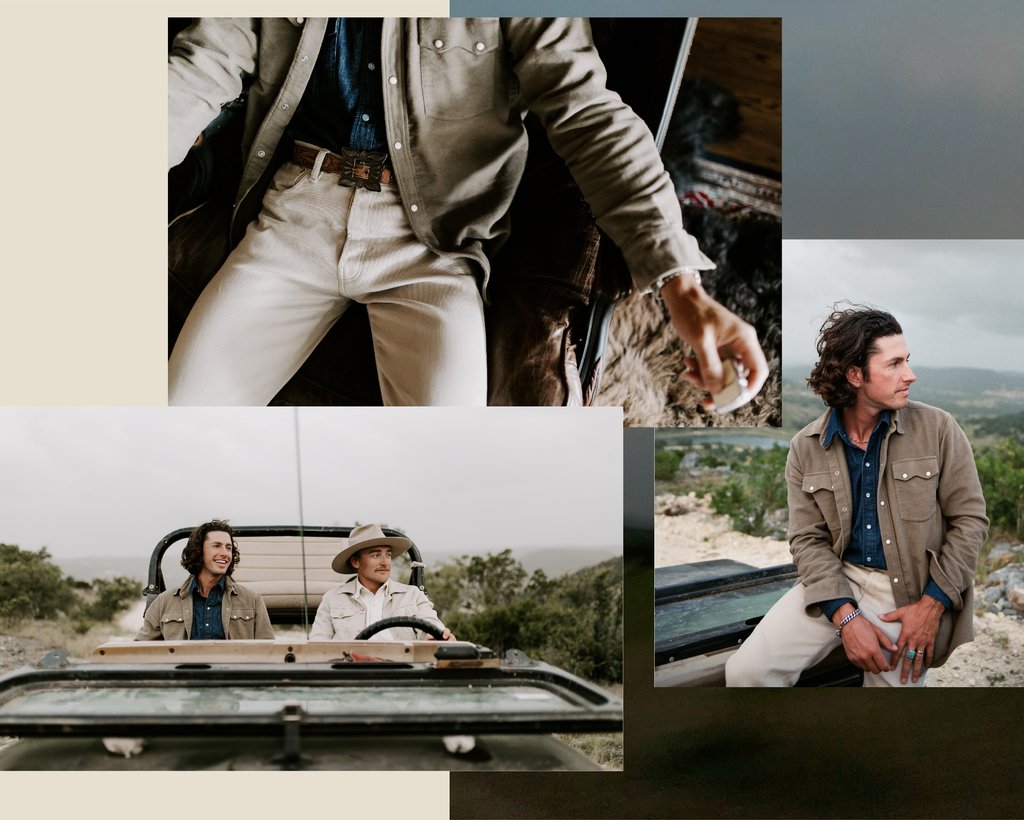

Peter Middleton’s new line, Wythe, freely mixes city and country, workwear and prep, dressy and casual. As a young man growing up in Texas, he spent summers in New York and rejected westernwear and prep as clothing for an older generation. It wasn’t until he moved to New York City that he started to see these clothes in a new light. “There was something different about the way guys on the Upper East Side wore their old Luccheses,” he says. “It had such a different attitude than the square-toed, rubber-soled boots I saw growing up. I saw people mixing different styles in a way I had never seen before. After a few years here, I started to really find my groove. I mixed vintage Lee Storm Riders with tailoring, oxford shirts with vintage British militaria. Wythe isn’t really about westernwear, but I think each season will always have a sort of nod to my background growing up in Texas.”

Wythe started last year as a Kickstarter campaign for the “perfect oxford shirt.” Their initial lookbook perfectly captured the mood of those warm, sultry afternoons in New York City spent inside. The campaign also had all the right trad verbiage, promising supporters that they would deliver an unlined collar with an enviable roll. At the time, Middleton had just come from a job developing luxury fabrics for Ralph Lauren, so his textiles experience seemed promising. “At Ralph Lauren, I learned how to work with mills to produce vintage-inspired fabrics,” he tells me. “So when I worked on my shirts, I showed the mills some of my vintage oxfords from the 1950s and ’60s. We worked together to make an authentic oxford cloth that still retains the slight irregularities and slubs that makes those old oxford shirts so amazing.”

This coming fall’s collection will still be based on shirts, but ones with a more rustic origin. “I did two styles other than oxfords,” says Middleton. “There are moleskin sawtooth Westerns made with pearl snap buttons and my signature feather-pleated back. Those will be available in four colors. There’s also an indigo denim Western shirt with French blue pearl snaps and a 1940s inspired back yoke. Over that, you can throw on a Shetland sweater or a cotton crewneck sweatshirt.”

I mostly like the collection because it looks like something you’d wear to a Fleetwood Mac concert (the band’s 1977 hit “Dreams” is the mega-chill anthem we need in this deeply unchill year). The lookbook has oatmeal-colored trucker jackets, saddle-shouldered Shetlands, and rustic Bedford cords. Accessories include hand-tooled leather belts and totes, which were made in Mexico. From this season’s collection, Middleton says he’s proudest of the dramatic topcoat made from an ombré, diamond-weave tweed. “I fell in love with some archival tweeds at a family-owned mill in Ireland,” he says. “So, I sent them some pictures of my old Beacon blankets that were made from a twisted ombré yarn. We worked out a special sequence in the warp yarns to recreate a tonal ombré pattern. It was a wild idea, and no one knew how it would turn out, but I remember the feeling of accomplishment when I saw the tweed for the first time at the New York factory. I knew the coat would be good.” You can find the collection, including the tweed topcoat, starting this Friday at No Man Walks Alone (a sponsor on this site).