“Polo” is the most confusing word in men’s fashion. When Brooks Brothers put their new button-down collar on sport shirts in the early 1900s, they marketed them as polo shirts. The tan, double-breasted overcoat popular with Ivy Style aficionados is called a polo coat. In Britain, the turtleneck sweater is sometimes called a polo jumper. Ralph Lauren named his mainline Polo. And for some reason, the tennis shirt is called a polo even though it’s more likely to be worn to play golf.

In the early 20th century, tennis was a sport of strict dress rules. Women played in blouses and full-length skirts; men wore cream-colored, cricket cloth trousers and full-sleeved, white oxford shirts, typically with the sleeves rolled halfway up to the elbows. Only a man of means could afford to indulge in a country club pursuit that came with a large laundry bill. Tradition-bound sportsmen found a snobby pleasure in sweating it out in stuffy, all-white uniforms. So when French player René Lacoste came onto the courts in 1927 with a short-sleeved shirt, he was responsible for a minor cause célèbre.

To be sure, Lacoste didn’t invent the polo. First seen on the French Riveria about two years earlier, it was taken up by fashion-conscious British players before getting the stamp of approval by young Americans on the courts of Palm Beach. But when Lacoste won the US National Championships that year — and several titles since — he helped popularize the style. In 1933, he partnered with a knitwear manufacturing entrepreneur Andrew Gillier to produce la chemise Lacoste, a lightweight, breathable piqué-cotton pullover with an unstarched collar, a three-button placket, and comfortable short sleeves. Known as the L.12.12, the shirt isn’t stiff, but it has rectitude. Tennis, after all, is often referred to as the “most genteel of sports,” so the tennis shirt – or polo — is in many ways the most genteel of sportswear.

In The New York Times, Troy Patterson once wrote: “The connotations of polo are elite but not effete. What is a polo player if not an aristocrat fused with a cowboy? And yet a ‘polo shirt’ sounds somehow more approachable than a ‘tennis shirt,’ probably because the equestrian game exists at such a ludicrous remove as to seem no more substantial than a mirage. The oddities attendant to the status of reappropriated symbols are delightfully rich. [The polo] is an everyman’s everyday everything.”

The polo is a signifier of prep insidership, but over the years, working-class youths have also appropriated the style. Ralph Lauren’s “big pony” shirt, for example, is a favorite of ‘Lo Heads, a loose collective of urban, often black, youths who collect Polo Ralph Lauren clothing. “In Mexico, counterfeit versions have been popular among high-level drug traffickers and, in turn, lower-class teenagers,” Patterson writes. “Four years ago, The Associated Press quoted a psychologist who hypothesized that the kids on the street were thumbing their noses either at the police or at everyone: ‘Many youths are also using it as a way of making fun of snobbish status markers.’”

Similarly, various British youth subcultures – Mods, ska heads, and skinheads among them – have adopted Fred Perry’s piped polo, with a triumphal garland on its chest, as part of their anti-establishment uniform. “It has not been lost on them that the [British tennis player Fred Perry] was a labor-class hero who legendarily weathered snubs lobbed by the toffs of the All England Club. The writer Ian Hough has discussed the message the shirt sent when worn by football hooligans in northern England: ‘The laurel wreath of Manchester’s Perry Boys said, ‘Look at us again, and you’re gettin’ filled in, sunshine.’”

Like suits, the history of the polo is about how each generation throws out everything in their father’s closet, particularly items they consider formal. Edwardian boots were, at one point, were replaced with leather slip-ons, but then tassel and penny loafers have been since replaced with sneakers. Similarly, what was once controversial sportswear is now just business casual. The polo shirt was punched in the gut when someone ripped out the Lacoste’s snappy alligator logo and replaced it with a company name and phone number. Today, the lightweight polo is heavy with social meaning. Tucked into chinos and you’re a golfing uncle. Collar popped and you’re the preppy antagonist in a bad 1980s film. Worn plainly on its own and you’re the sentient version of that sliced cantaloupe platter at every business conference. As if those connotations aren’t bad enough, the polo was dealt a deathblow in 2017 when white supremacists appropriated the floppy white shirt as part of their uniform at the Unite the Right rally.

Still, the polo has its virtues. Its stretchy knit fabric is more forgiving than a woven button-up. On hot summer days, it can be tender mercy indeed. It requires little to no ironing, making it the perfect travel shirt or ideal for lazy Sunday mornings. And in an increasingly casual world, the soft, unstarched collar frames the face better than a crewneck t-shirt, but is free the button-up’s stiff ceremony.

Polo shirts can be worn well, but it helps to avoid looking like a middle manager at a corporate retreat. Instead of the plain, piqué cotton varieties that litter every mall, try something with a deeper placket, more interesting collar, and some long sleeves. Polos are usually best without the chest insignia that wears like a boutonniere – smirking whales, galloping horses, leaping marlins, waddling penguins, and even the original snapping alligator (sorry Lacoste). Solid and simple colors, such as navy, white, and light blue, can be easier to wear than preppy pastels.

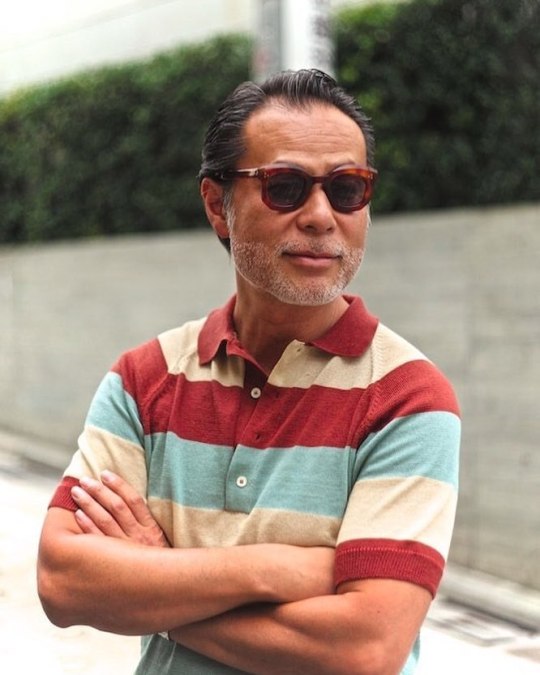

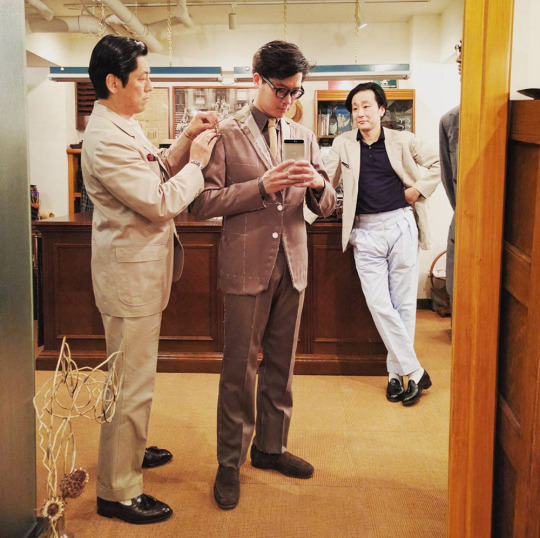

I particularly like them underneath casual sport coats, but the collar has to be able to stand up on its own, either with a one-piece collar or shirt-like collar band construction. The Armoury, G. Inglese, Lost Monarch, Kent Wang, Luca Avitable, Christian Kimber, and Eidos’ Lupo are great for this sort of thing. In East Asia, you can find similar polos from BRIO, Yeossal, and Zing Chen. In the photos above, Charlie from Canberra, Australia can be seen wearing a Zing Chen polo with an Eidos sport coat. “The collar is pretty floppy but the points are long, so the collar folds up nicely underneath a jacket’s lapels and stays there,” he says. In the US, Zing Chen’s polos can be bought through Taobao or by messaging them on Instagram.

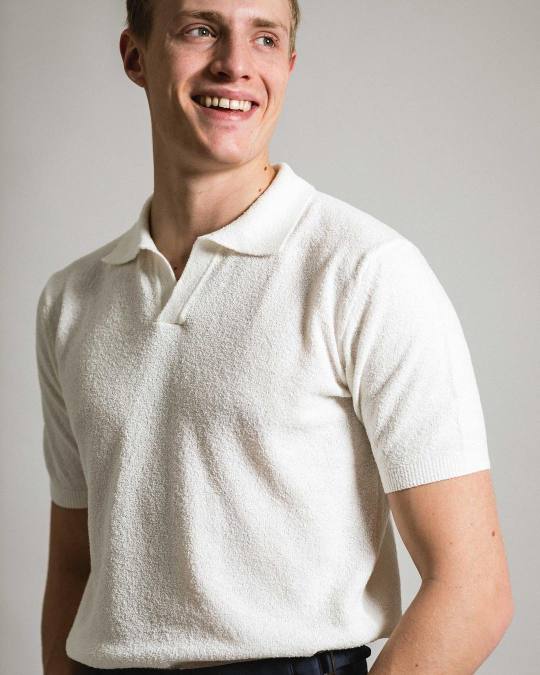

If you’re looking for something you can wear on its own, I like the retro-inspired styles at Linnégatan 2. Stoffa’s band collar polos are great with smart casualwear, and they have a piqué cotton button-up with a generous collar. Luca Faloni and Sunspel are a little more basic, but also solid upgrades from the kind of polos associated with corporate anonymity. Additionally, polos can be made from more unique materials, such as knitted wools, crunchy linens, and even terry cloth. You can find those from Berg & Berg, Timothy Everest, De Bonne Facture, and Camoshita. Finally, something as simple as a ribbed hem can make all the difference. The Ban-Lon offers a louche 1960s nightclub alternative to the tennis shirt’s ‘80s country club aesthetic. They look good in that Tom Ford/ Gucci way – both brands that have offered them in the past, although this season you’ll have to turn to McLauren, John Smedley, and online vintage shopping.