In the mid-1920s, the press snapped a photo of the renowned radiologist Dr. Alfred Charles Jordan as he was cycling to work at his Bloomsbury practice. Soon after, the picture was published in a British newspaper, where it scandalized readers. Jordan was shown wearing a pair of shorts with a tailored jacket. At the time, no man in the city, and certainly none in professional life, bared his knees in public. Shorts were for children and perhaps people hiking on holiday. Even tennis players in the 1920s wore cream-colored flannel trousers when playing sports.

Jordan went on to be one of the founding members of the Men's Dress Reform Party, a flock of odd ducks in Britain who believed there was an intimate connection between clothes and health. Founded in June 1929, after a meeting at 39 Bedford Square in London, the Party sought to reform men's dress so that it could catch up to the progress they felt womenswear achieved. Members believed that men's clothing was too tight, ugly, and cumbersome, and before the adoption of dry cleaning, unwashable and thus unhygienic. “The Committee believes it would be premature to offer fixed and final views,” they wrote in their first publication. “Indeed, the men's dress reform movement should have as one of its aims the encouragement of a somewhat greater range of individual style than is possible with men's stereotyped costumes.”

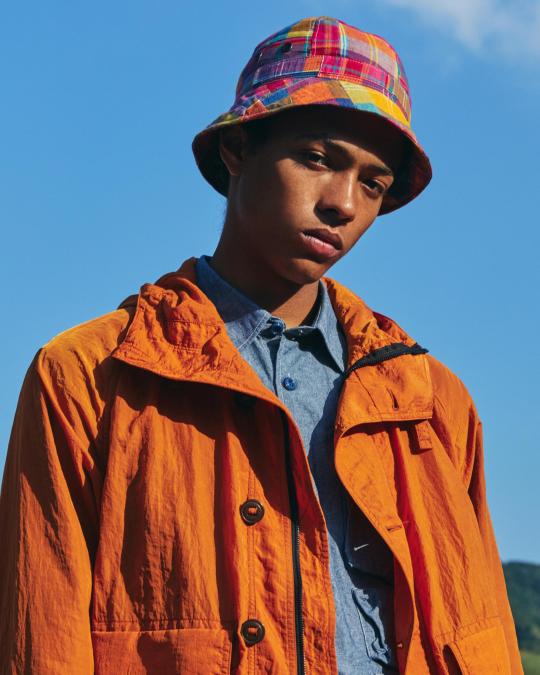

For generations up to this point, "proper attire" in Britain was regulated by time, place, and occasion. Men wore dark worsted suits and black calfskin oxfords in the city, then tweeds and brogues for sporting and leisurely activities in the countryside. The members of the MDRP, however, wanted to free men from the shackles of social convention. They didn't just want to banish the suit; they want to replace it with holiday attire. For work in the city, members felt that men should be free to wear soft, open-collared shirts made from colorful rayons and fine poplins, which they thought paired well with jacket-and-shorts suits and matching wool stockings. "Most members wish for shorts; a few for the kilt; nearly all hate trousers. Some plead for less heavy materials and less padding; others for brighter colors," the London Times reported in 1929.

Keep reading