Marcel Duchamp once noted in a 1968 interview with Francis Roberts, “If your choice enters into it, then taste is involved—bad taste, good taste, uninteresting taste.” For those fortunate enough to live in post-industrial societies, where choices are now nearly limitless, taste is everything. Taste shapes what we purchase, the cultural artifacts we consume, how we dress, and how we decorate our living spaces. In the 19th century, standards for taste were passed down through aesthetic curricula conceived in formalized education systems. To have a certain type of taste was to show that you were educated and cultivated. Those standards have not been culturally relevant for over two generations, and thus, debates about taste take place everywhere. They happen in public spaces such as public transport, cafés, and boutiques, where people speak in hushed tones about other people’s consumer choices. They also happen on social media and online forums. On Hacker News, a message board for tech workers, people discuss what constitutes a tasteful wardrobe. On subreddits and Facebook groups dedicated to topics wholly unrelated to fashion, such as motherhood and accounting, people post fit pics for feedback. Godwin’s Law asserts that all online discussions, no matter the topic or scope, eventually result in someone comparing their opponent to Hitler. There should be a similar adage for how all discussions eventually lead to matters of taste.

Yet, despite all the interest in taste, few people ask the more fundamental questions: What is good taste? How do you cultivate it? If you’re just starting to build a better wardrobe, how do you adjudicate between the different and often contrasting styles prescribed by hard-nosed traditionalists, Hypebeasts, gothninjas, workwear enthusiasts, and the avant-garde? Discussions about taste frequently take too much for granted, as though the laws governing aesthetics were chiseled into stone tablets. Or they fade into unhelpful aphorisms, such as “to each his own,” at which point participants all quietly drop the subject, not wanting to ruffle feathers.

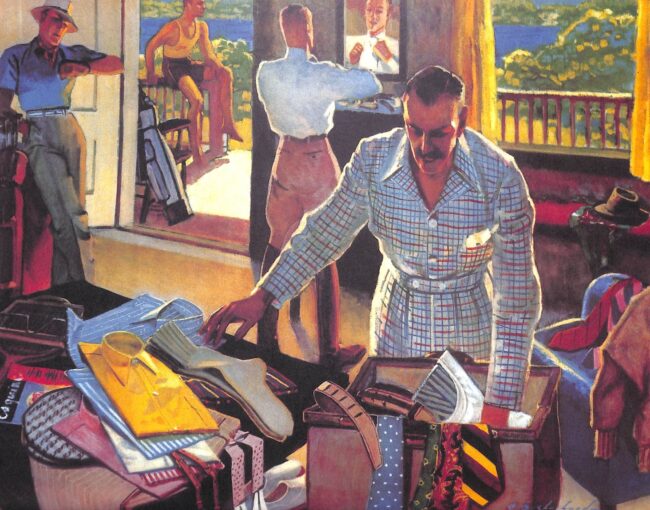

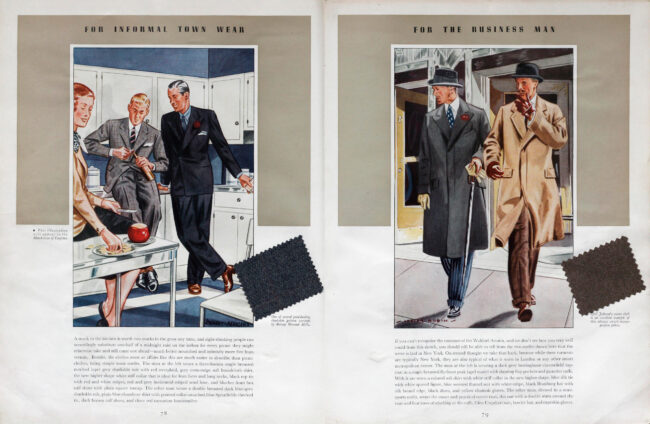

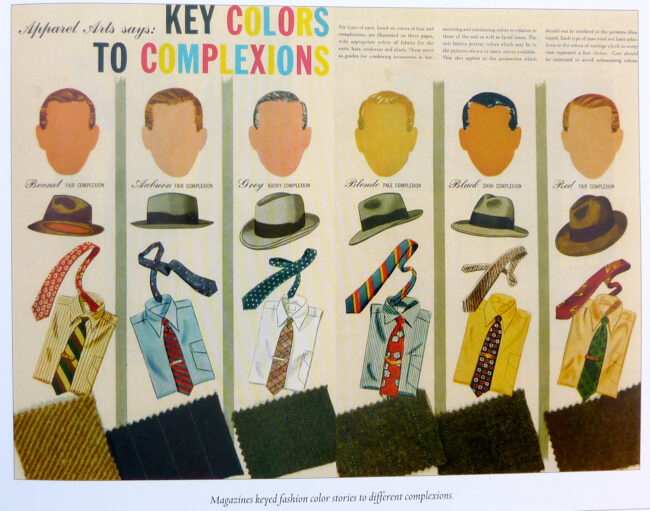

I’ve been thinking about taste a lot in the last few months. Fifteen years ago, if you were interested in classic tailoring, online debates about taste were settled with a scan from Apparel Arts or a photo of how an Italian industrialist dressed during the 1960s. Today, few people care about classic tailoring, and such specialized source materials hold little authority. In recent years, the scope for what we consider “legitimate taste” has widened to include a broader cross-section of society (a good thing). However, it has also become harder to critique ugly outfits (a bad thing). It’s also harder to discuss aesthetics, as menswear has become balkanized, and The Discourse is increasingly about how to shop, not dress (a frustrating thing). So, I wanted to write a multi-part series on how to develop good taste. The first part is about theory; the second part is about practice. To be sure, this series will not settle any debates. But hopefully, it will give people better footing when discussing what lies at the heart of menswear: our taste in clothes.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DRESS THEORY

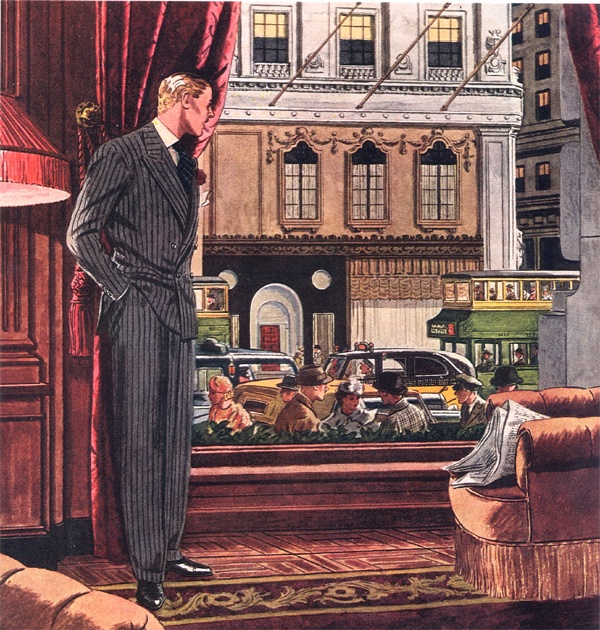

The first thing to understand about taste is that our judgments are not neutral or objective, but rather rooted in social identity and meaning. To understand this, we have to go back to the turn of the twentieth century, when the United States was marching toward a new era of modernity, fueled by the upbeat energy of industrial capitalism. Just before this period, the fustian lounge suit—what we today would call a business suit—was the uniform of broker citizens, such as shopkeepers, clerks, and administrators. But at the turn of the 20th century, the monochromaticity of the dark worsted suit worn with a white linen shirt and dark silk tie constituted a capitalistic aesthetic. It became the uniform of newly minted businessmen and rising politicians, making it a symbol of snappy progress. Likewise, middle-class women in urban centers, flush with newfound capital, wanted to dress more like their sophisticated European counterparts. And rural women wanted a taste of city fashion.

In this march toward modernity, an army of Americans, mostly made of women, geared up to help ordinary people dress better. They were writers, teachers, and retailers who authored thousands of books, pamphlets, and magazine articles on the art of looking good. They taught university classes, hosted radio shows, and incorporated their lessons into weekly clothing club meetings. For about a forty-year period starting in 1923, they even partnered with the federal government. The Bureau of Home Economics, a division of the US Department of Agriculture at the time, had a number of initiatives to support homemakers. These initiatives included writing and publishing sewing patterns and repair manuals to help women “make do and mend,” so they could better carry their households through The Great Depression and Second World War. The bureau even published menswear pamphlets teaching men how to buy better suits and dress shirts, as well as take care of these items so they’d last a lifetime. For these style experts, the message was simple: knowledge, not money, is the key to style. First Lady Elanor Roosevelt summed up this sentiment neatly in her book It’s Up to the Women, published during the depths of the Great Depression:

Do not think, however, that the price which you pay for clothes means a well-dressed or poorly dressed woman. A ten-dollar dress, if you have good taste, may be just as pretty as one for which you have spent ten times as much. I have seen women who spend very small amounts on their clothes but who plan carefully, frequently look better-dressed than women who waste a great deal of money and buy foolishly without good taste.

Similar to the Enlightenment philosophers a few centuries earlier, these style specialists held that good was preferable to bad, progress was possible, and the precepts of nature—here being those that govern aesthetics—could be reasoned out like the axioms of mathematics or physics. Mary Brooks Pickens was one of the first and unquestionably the most well-regarded of these style authorities. As the founding director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, which today hosts the annual Met Gala, she wrote nearly a hundred books about the science of style. In her 1918 book The Secrets of Distinctive Dress, she taught women how to dress for their body type, identify beautiful lines, and choose suitable fabrics for various occasions and activities. “An artist must know the principles of art to enjoy art or to make a success of it,” she wrote in the book’s foreward, “and so must every woman know the principles of dress and enjoy dress to be successfully clothed.”

During the same period, Harriet and Vetta Goldstein led the way in making beauty accessible to everyone. They believed that the spiritually uplifting power of beauty should not be limited to the expansive mansions and fine art pieces that only the extravagantly wealthy could afford, but should be imbued in the common and everyday objects surrounding ordinary people. In some ways, they were carrying forward the American version of the British-born Arts and Crafts movement, whose founder William Morris once declared, “I do not want art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few.” Beauty is for everyone—and everyone can be beautifully clothed, should they know some basic rules.

As instructors at the University of Minnesota, the Goldstein sisters taught students how to solve complex design problems through the use of formal analysis. They also presented their ideas in a general audience book they simply titled, Art in Every Day Life. “Good taste, in the field of art, is the appreciation of the principles of design to the problems in life where appearance, as well as utility, is a consideration,” they wrote in the first chapter. “Since art is involved in most of the objects which are seen and used every day, one of the great needs of the consumer is a knowledge of the principles which are fundamental to good taste.” The book then moves through what the sisters considered to be the five governing principles of good design, with each principle given its own chapter: harmony, proportion, balance, rhythm, and emphasis.

According to the Goldsteins, these principles are present in all forms of beauty. You can find them in floral arrangements, home furnishings, textile design, great masterworks of art, and architecture. The chapter on harmony shows how intersecting lines help create a pleasing structure in Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, not unlike how Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier might design a home. “The dominant direction of the lines of the picture is horizontal, repeating the shape of the picture,” they explained. “The vertical line is introduced to strengthen the arrangement and to suggest variety. The diagonal line gives a note of variety, but it is stopped by the use of the horizontal line before it becomes too vigorous. The transitional line of the pediment over the doorway is introduced to modify the sudden change, and to give unity.”

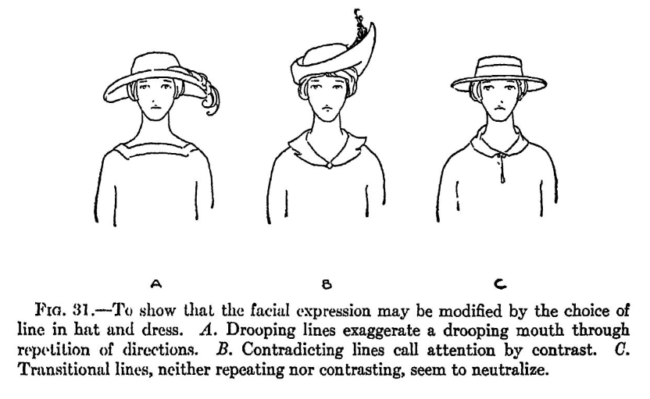

The Goldsteins recommended using these same principles when choosing a hat. If a woman has a resting frown, where the corners of her mouth naturally turn down, she was advised to choose a hat that neutralized or countered these lines. “Drooping lines exaggerate a drooping mouth through repetition of directions,” they claimed. In a later chapter about emphasis, the sisters observed that “[t]he eye and the mind do not enjoy a haphazard collection of shapes and colors.” All compositions, whether in triptych art or interior design, should gently lead the viewer’s eye from one point in the arrangement to the next, so that everything works as a coherent scheme. According to the Goldsteins, this same principle can be used to enhance a person’s appearance. They wrote of successful dress design: “The contrast of the light yoke has centered the interest near the face so that one is more conscious of the wearer than the dress.” Alan Flusser would carry this same idea forward nearly a hundred years later in his book Dressing the Man. According to Flusser, all classic men’s outfits should lead the viewer’s eye upwards toward the person’s face, their most animated feature and the expression of their personality, which puts the focus on the person and not their clothes. (This is partly why classic menswear outfits don’t work with alien-looking shoes—green oxfords, bi-material boots, and purple alligator loafers, despite their popularity on shoe blogs and Instagram accounts. Such shoes drag the eye downward and create two competing points for attention. Even walnut-colored shoes require some consideration to wear well.)

Historian Linda Przybyszewski wrote about this rational approach to style in her 2014 New York Times bestseller The Lost Art of Dress. Using a story about how Mary Brooks Pickens once helped a woman climb the ranks of her medical profession by advising her on how to dress better, Przybyszewski dubbed these early-20th century style authorities “The Dress Doctors.” An excerpt from her book:

They explained that the same principles [in art] should be used in the design of clothing. Their aim was the creation of what they called ‘artistic repose,’ the moment when the discerning eye takes in a design as a whole and finds it perfectly satisfying in color, line, and form. […] The schoolgirl’s clothing, whether day wear or evening wear, remained simple in cut so that she could move her energetic body freely. The bright and playful colors she wore reflected her youthful energy and simplicity. Aging meant gains in worldliness. The Dress Doctors reserved for the woman over thirty the most complex dress designs and the subtlest color schemes. They explained how a woman can age with grace and dignity by using the right hues and fabrics. […] Instead of advising on trends that would soon be obsolete, the Dress Doctors taught the rules of good design. Armed with these truths, a woman in any era could determine for herself what was beautiful, while the lessons on budgeting from the same advisers kept her out of debt.

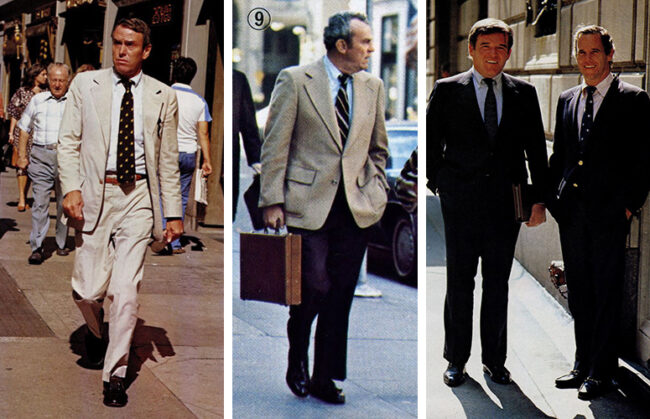

Although this approach to dress began to wane after the social revolutions of the 1960s, it remained in niche circles well into the twilight of the 20th century. In 1975, John Molloy helped popularize the idea of “power dressing” through his New York Times bestseller Dress for Success. As a self-styled “wardrobe engineer” who consulted for a number of corporations—General Motors, United States Steel, and Merrill Lynch among them—Molloy dressed up his fashion theories with pseudo-scientific language, social experiments, and surveys. “Those of you who are, at this point, saying that fashion is an art form and not a science are making the same kind of statement as the eighteenth-century doctors who continued to bleed people,” Molloy wrote. “I do not contend that fashion is an absolute science, but I know that conscious and unconscious attitudes toward dress can be measured and that this measurement will aid men in making valid judgments about the way they dress.”

“There are men in the fashion industry who try very hard to make men look ‘good,’” Molloy continued. “We know they are trying hard because their livelihoods depend on their success. But like the medical men prior to the scientific method, their attempts are made ineffective because they use subjective methods. A designer sits alone in a room and decides that a particular garment will make men look good. He does not bother to ask other men their opinions of the garment; he does not measure what the world thinks of it. He does not apply any scientific principles to arrive at his decisions, and therefore his judgment has all the validity of the seventeenth-century doctors’ judgment: it is articulate; it can be systematized; it can be defended in all ways except before the avalanche of evidence. And I believe that this book is the first rumble of that avalanche.”

Dress for Sucess is an auto-mechanic guide to style. In Molloy’s words, men should learn how to use clothes “as a tool and as a weapon” to get ahead in life. “[W]hen we say that clothing can make a man look ‘good,’ we are really saying that it makes him look authoritative, powerful, rich, responsible, reliable, friendly, masculine, or any other trait that is meaningful to us and meets with our general approval.” To achieve this, the book goes through how men can project authority or build rapport by marshaling minute details such as monograms, shoes, fountain pens, attaches, socks, umbrellas, and neckwear. An amusing ten-page chapter delves into how men can use chest hair and color to attract women. One of the book’s more memorable sentences, which made me chuckle, is buried in the last chapter: “women are turned off by traditional clothing.”

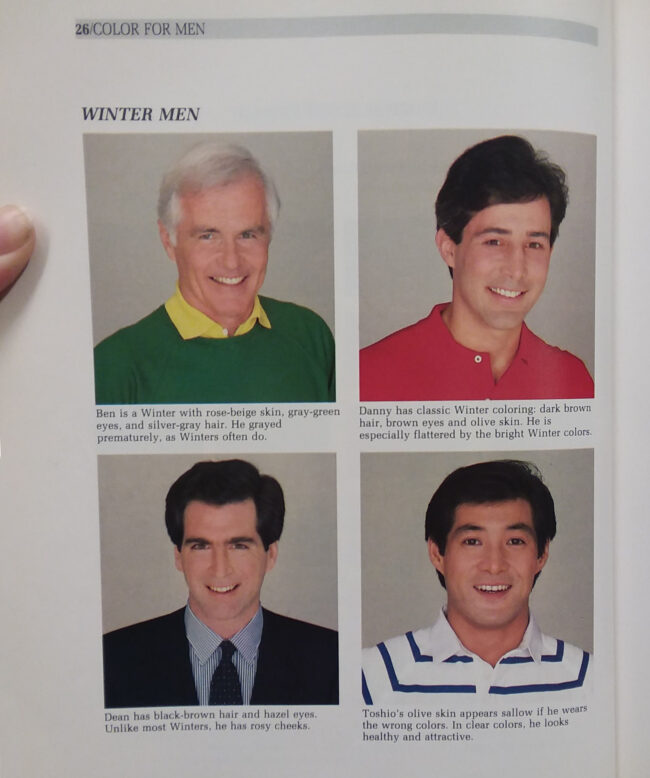

Even the application of colors has been systematized. In her book Color for Men, published in 1987, Carol Jackson took the color theories that women used in the 1970s to choose makeup and turned them into tips for how men could choose better fabrics for their skin tone. According to Jackson, people came in one of four seasonal colors—spring, summer, fall, and winter (the process of figuring out your season is a bit maddening. I’m winter … I think). Wintery men have skin tones ranging from rose-beige to olive; their hair could be anything from black to brown (greying early). The book claims that wintery men look sickly and sallow in lighter-colored jackets, such as those in wheat or camelhair. Jackson encouraged such men to wear dark suits, white shirts, and dark ties, which enliven their look. By contrast, spring men benefit from wearing lighter-colored jackets because they have peach-pink complexions, light reddish hair, and blue eyes. Navy suits and ivory white shirts, it was said, drained color from their faces. Since the book’s publishing, Jackson’s theories have been endlessly recycled, showing up in one form or another in various menswear blogs and books.

Longtime devotees of classic men’s style will undoubtedly be familiar with Alan Flusser, whose 2002 book Dressing the Man came just before the classic menswear revival of the mid-aughts. Of course, Flusser already had an illustrious career up to this point. He dressed many of Hollywood’s most iconic and stylish characters—Gordon Gekko in Wall Street, Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, and Lt. Col. Frank Slade in Scent of a Woman. His books Making the Man (1981) and Clothes and the Man (1985) also followed in this analytic dress tradition. Flusser encouraged men to keep to Goldilocks proportions, such that nothing ever veered towards the extremes. Sensible lapels were to end halfway between the collar and shoulder seam; jackets terminated halfway between the collar and the floor. In this way, a garment’s design would always be within striking distance of any trend, increasing its life expectancy.

Other ideas, such as Flusser’s suggestion that side vents and higher gorges give a man an added sense of height, are a little more dubious. The color section in Dressing the Man is the weakest section of the book, as it relies on such dramatically different pictures—varying by wearer, background, and garment—it’s difficult to judge whether different men truly look better in certain fabrics. Nonetheless, Flusser has made the language of classic men’s style a little more legible to people who may not have grown up in a coat-and-tie. He’s helped keep this style relevant for another generation. For people who have a particularly warm affection for this style of clothing, including me, he and other such writers—Bruce Boyer, Will Boehlke, Simon Crompton, Bernhard Roetzel, and Torsten Grunwald among them—should be commended for that alone.

THE UNDERPINNINGS OF TASTE

This analytical approach to style is so common that it can almost feel natural. On menswear message boards such as StyleForum, nearly every discussion feels like it’s part of The Dialectic, where members argue like Athenian philosophers or Tibetan monks over whether blue pairs with black, or if a shoulder seam is sitting in its “correct place.” If you look below the surface, however, you’ll find this approach has some important underpinnings that date back to the Enlightenment. Immanuel Kant, at first glance, seems like an unusual figure to reference in menswear. He was not particularly interested in clothes and had a generally negative view of fashion. Among his three critiques, he’s most famous for his first book, The Critique of Pure Reason. The Critique of Judgement, sometimes called the “third critique” because it came last, is the one that concerns itself with aesthetics. It seems like a diversion for a German idealist who primarily wrote about epistemology and ethics. However, Kant’s contemporaries Schelling and Hegel considered it one of his most important works (Schelling once advised students to read the three critiques in reverse order). Widely regarded as a seminal work on modern aesthetics, The Critique of Judgement has influenced how we view everything from paintings to pinstripes.

“In the classical European humanistic tradition, fashion was always thought to be antithetical to good taste,” Jukka Gronow writes in The Sociology of Taste. “A person blindly following the whims of fashion was without style, whereas a man of style—or a gentleman—used his own power of judgment. Immanuel Kant shared this conception with many of his contemporaries.” According to Kant, judgments of beauty are best conceived as a “disinterested pleasure.” They shouldn’t be influenced by information or ulterior motives. The viewer should also not seek anything from the object or make demands. For instance, you don’t need to know anything about a rose to appreciate its beauty (and conversely, you shouldn’t believe something is beautiful just because it’s intellectually interesting). It also shouldn’t matter if roses are trendy, or if owning a rose confers social status or the possibility of financial reward. You should be able to appreciate the beauty of a rose on a warm mid-summer day stroll, purely by virtue of seeing its form and bounded dignity. The appreciation is visceral and emotional—it’s a pure, disinterested pleasure. And although your appreciation of a rose rests within you (making it subjective), you assume that others will agree when you say “that rose is beautiful” (making the subjective experience universally valid). For Kant, this universality of beauty—or the universality of good taste—presumes that we, as humans, share a “common sense.”

In fact, the Latin maxim de gustibus non est disputandum (“in matters of taste, there can be no disputes”) did not originally mean that a person’s subjective taste is of no concern to others. “On the contrary, matters of taste were thought to be self-evident and judgments of taste, at least in principle, generally shared by all,” Gronow elaborates. “There could, thus, be no good reason or ground to argue about them. A false judgment of taste was caused either by ignorance or error. According to this interpretation, judgments of taste concerning the beauty of objects were ultimately based on feelings of pleasure and displeasure: what felt good was both right and beautiful.” In his treatise on aesthetics, Edmund Burke posited that, once the possibility of error has been overruled, only a fool would fail to recognize the “most excellent and venerable.”

Of course, there’s another point of view. A more compelling view, in my opinion, and one that takes into account social meaning, temporality, and historicity. This is the sociological perspective on fashion and taste. It doesn’t assume that style rules were handed down like manna from heaven. Or that they emerged whole and pristine, like Athena from the head of Zeus. In fact, it posits that such analytical approaches only conceal how different forms of taste create social distinctions in a system of competitive classifications. Dress is fundamentally about sociology, culture, semiotics, history, and personal identity. To understand style and develop a better sense of taste, we have to treat dress practices as a kind of language (sometimes called “the vibe”).

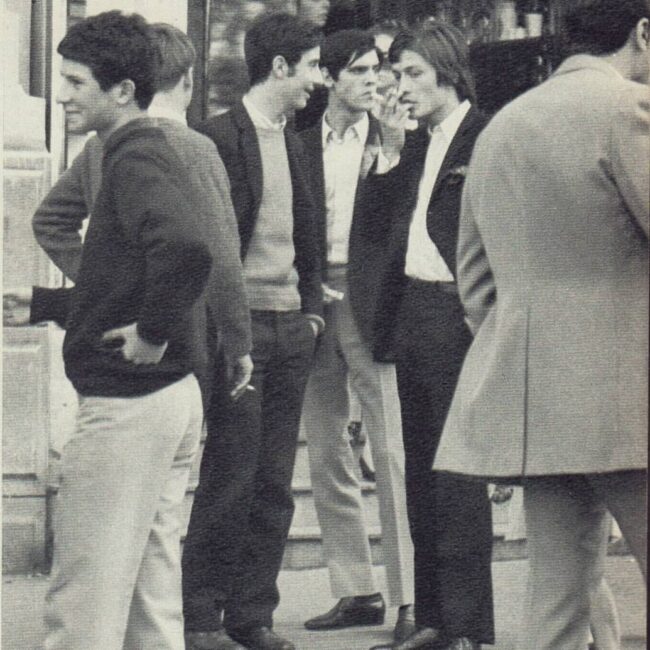

On a fundamental level, we can not understand the suit and its traditional dress practices without contextualizing it in terms of the emergence of capitalism. We can not explain its spread without also talking about the rise of the Second British Empire. Similarly, we can not talk about the explosion of different modes of Western dress during the 20th century—stretching from the mania for Orientalism in the early 1900s to the peacock revolution of the 1960s to the rise of streetwear by the twilight of the century—without talking about the evolution of liberalism, industrial mass production, and consumer-orientated societies. Fashion, or style, if you prefer, is fundamentally about stories. We know this because the word “text” comes from the Latin term textus (“a tissue”), the past participle of the verb texere (“to weave”). Stories and clothing are interlinked even on the etymological level.

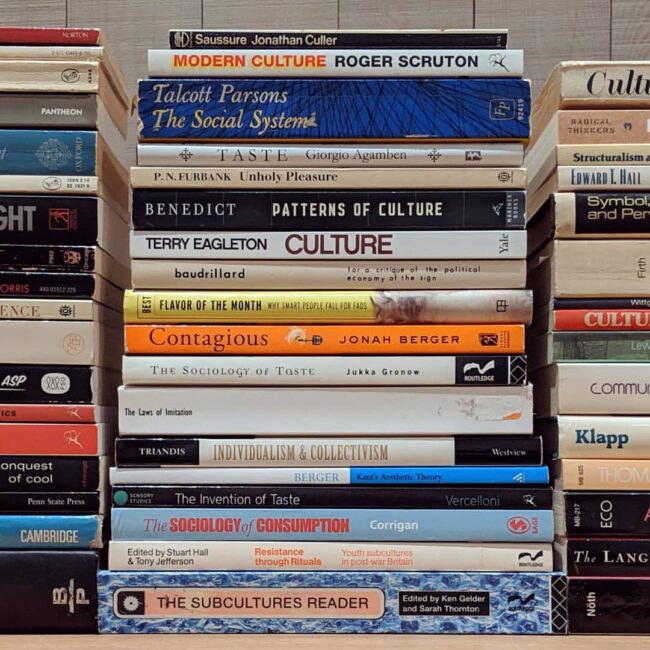

There are too many good authors in the sociological tradition to cover meaningfully in a blog post. Georg Simmel, Terry Eagleton, Thorstein Veblen, Norbert Elias, and others have written about communities of taste, the associative nature of dress, and how goods and social practices are appropriated as status symbols. David Marx, the author of the brilliantly researched Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, is coming out with a book next month about how our pursuit of social status shapes our most profound personal desires and drives cultural change. One of the more concise passages I’ve come across for this view was written by James Laver, who has been described as “the man in England who made the study of costume respectable.” In his book Taste and Fashion, he wrote: “In every period costume has some essential line, and when we look back over the fashions of the past we can see quite plainly what it is, and can see what is surely very strange, that the forms of dresses, apparently so haphazard, so dependent on the whim of the designer, have an extraordinary relevance to the spirit of the age.”

For the purposes of this post, we’ll focus on just one author: the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu, like many academics of his generation, dressed with the quiet sophistication associated with a life of the mind. He wore open-collared button-downs, classic worsted suits, and rustic sport coats decorated with tweedy birdseye and herringbone patterns. His shoulder line was padded but not rigid; his coats lacked dandy flourishes, such as the frog-mouth lapels (cran necker) indicative of French bespoke tailoring. But it was his academic work, not his clothes, that enabled him to speak more deeply about men’s dress issues. Bourdieu was primarily interested in how power spreads throughout society, often in subtle and generational ways. He wrote about how upwardly mobile social groups and the ruling class serve as a cultural vanguard, creating increasingly fine distinctions in lifestyle and etiquette. Even oppressively normal activities, such as eating, are treated as arenas for social competition. “Complex small but expensive dishes, a complicated hierarchy of tastes, and even the ability to discuss and argue about taste, cuisine, and cooking methods” make it possible to create increasingly refined distinctions. This elaborately differentiated system then becomes a way for participants to climb the social ranks. Having a sophisticated palate for French cuisine and fine wine signals that you are part of the cultural elite, whereas having an equally refined palate for Vietnamese food does not confer the same status.

For Bourdieu, taste is about class. His main criticism against Kant’s pure aesthetics—and The Dress Doctors and post-war menswear writers, if he had addressed them directly—is that they conceal the class origins and interests of their taste by constructing a seemingly objective and disinterested facade. In this view, there is no such thing as genuinely good taste. There is only legitimate taste, which presents itself as the universally valid form of good taste, but, in reality, it is nothing more than the taste of the ruling class.

To exhibit good taste is to put yourself in closer proximity to elites, if not to be within their company. “Anyone who showed good taste in their choices and conduct was a gentleman (or gentlewoman). Good taste, thus, was both an indicator of belonging to ‘good society,’ and the main criterion of entry into it,” Gronow explains. “Taste was essentially both an aesthetic and a moral category; in other words, these senses could not be separated from each other. Thus, decent conduct, dress, and decorum were all indicators of an individual’s moral and aesthetic value, or good taste. What was tasteful was both decent and virtuous, too.”

We see this dynamic at work today when we browse menswear blogs and forums. When you look across the entire landscape of men’s dress—which is made of balkanized communities oriented around niche aesthetics, such as workwear, streetwear, and the avant-garde—classic menswear is the only one that routinely gets wrapped with moralizing language about respectability. Of course, we should all strive to practice the kind of virtues Cardinal John Henry Newman described in his essay on what it means to be a gentleman. But discussions about the respectability of dress are rarely so thoughtful. Instead, they are often about a suited man wishing to signal his supposed social status in relation to the hoi polloi. In this way, dress and etiquette become nothing more than aping the aesthetics and behavior of the ruling class. Critical theorist Max Horkheimer described this dynamic as a kind of internalized repression, “inserting social power more deeply into the very bodies of those it subjugates.”

The tragedy is that none of these things are enough to fashion you into a gentleman, even in the socio-economic sense of the term. In drawing a comparison between Bourdieu’s study of modern France and Stephen Mennell’s historical research on England and France in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Gronow writes:

The lifestyle of the modern ruling class or bourgeoisie resembles that of Mennell’s court nobility: knowledge of etiquette is self-evident and its members are sovereign in their mastery of good manners. All the sensual and corporeal aspects of eating are concealed behind the strict formality of table manners. Pleasure is anticipated and constrained rather than satisfied. The modern French petit bourgeois is a typical parvenu, a country squire or nouveau riche who longs for rules and guidance in etiquette, for gastronomic guide books, in order to be able to live à la mode but never really succeeding in his efforts. He only reveals his real social origins by the insecurity of his conduct and by following the rules of etiquette all too rigorously. The main problem is not the thickness of the wallet, but rather the fact that it takes more than that to make a gentleman.

HOW TO DEVELOP GOOD TASTE

The deepening of democratization and industrial mass-production, as well as the evolution of consumer societies, have all destroyed the old rules and rhythms of fashion. Cultural influence can now spread throughout a complex network rather than flow just from the top down. I think this change is generally a good thing and it has made our world aesthetically richer. The ruling class may draw aesthetic inspiration from the working class, who may draw inspiration from a particular musician or artist. Cultural power is no longer just about money and bloodlines; it can bloom from merit, virtue, and talent. We also live in different cultural communities that can operate according to their own notions of taste; we don’t have to follow whatever is set by an archduke of a Vogue editor. In a 2015 New York Times article, fashion critic Cathy Horyn wrote eloquently about a “post-trend universe,” where “there is no single trend that demands our attention, much less our allegiance, as so many options are available to us at once.” Kennedy Fraser noticed the same thing when she took her post as a fashion columnist for The New Yorker in 1970. “After [1970], there was no longer any unabashedly accepted, universal fashion authority, and no real point in reporting the latest word of fashion news each season,” she wrote in the foreword of The Fashionable Mind. Style and taste have never been more democratic.

The paradox of modern society is that people are relatively free to choose how they present themselves, while at the same time, are almost forced to construct a cultural identity through a series of consumer decisions. Whether we choose to or not, we broadcast our identity through the goods and practices we possess and display. With so many choices today, many people are left anxious. “Am I wearing the right thing to the office?” “How do I dress for this summer barn wedding?” “Does my wardrobe reflect who I really am?” This is largely why taste has become such a salient topic of modern life.

So how does one develop good taste? Let me offer some suggestions:

Start With An Aesthetic: Everything is contextual to an aesthetic. A hundred years ago, the scope for good taste—what Bourdieu would describe as legitimate taste—was confined to the taste of the ruling class. That is no longer the case today. This means rules about colors, silhouettes, proportions, and other such ideas are contextual to the aesthetic you’re trying to create. I’ve written some posts about how to think about silhouettes and color. But whenever a reader emails me to ask whether black pairs with blue or if a particular garment fits correctly, I feel that, in today’s culturally open world, you have to start with the aesthetic, not compartmentalize things as universal rules. This is partly why some guys who favor classic tailored clothing struggle with casualwear—they try to transport cultural ideas about suits and sport coats to very different aesthetics, such as workwear or sportswear. Sometimes rules can stretch across aesthetic spaces (like ideas linking romantic languages); sometimes, they do not (like trying to apply English grammar rules to Chinese). Derive your rules from aesthetics and your aesthetics from culture.

Think Of Fashion As Language: Questions about taste are more easily answered if you think of fashion as language, rather than purely as artistic expression. MIT linguist Noam Chomsky is famous for his phrase “colorless green ideas sleep furiously,” which is an example of a sentence that is grammatically correct, but semantically nonsensical. A “good” sentence is more than just following grammatical rules; it’s about taking into account how different parts come together to create meaning. Take a look at the Instagram accounts for companies such as Aime Leon Dore (inspired by 1990s NYC), Savas (sophisticated rock ‘n roll), Canoe Club for Story Mfg (community gardener), and J. Press (American Ivy). All of these accounts rely purely on photos and videos—no words. Yet, they are able to communicate complex stories about identity and culture. Consider your outfits as a similar form of visual communication.

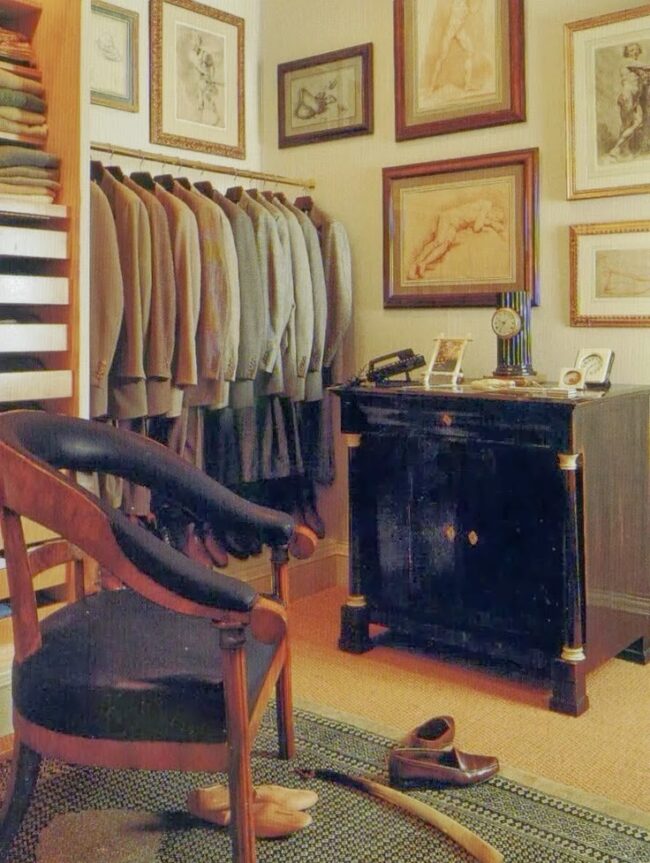

Develop Your Vocabulary: Pay attention to films, TV shows, books, art, music, and the various subcultures in different eras (both contemporary and historical). This is not because, as the Goldsteins suggested, the principles that define good art can be used to create good outfits. It’s because fashion is a reflection of culture. Clothes carry the messages we use to convey our identity, whether real or aspirational. Paying attention to culture can help you broaden and hone your vocabulary. If you love classic menswear, as I do, the best way to understand that aesthetic is to review how Hollywood stars, European industrialists, American intellectuals, and Old Money elites dressed from the 1930s through the ’80s, since they defined that fashion. (It goes without saying that I think you can love this aesthetic without being classist about it.) You don’t have to be a strict recreationist and dress like Cary Grant in North by Northwest. But knowing the basic contours of that look can allow you to express it in more natural ways today without losing sight of what makes that style so charming in the first place.

Think Of The Whole Package: This is a complex topic, and it can’t be easily distilled into advice. But the general idea is to be truthful about how your dress interacts with your physical appearance and lifestyle. On the one hand, it’s always easier to dress according to your stereotype—a husky man can look great in workwear in a way that a very skinny person may not be able to pull off. At the same time, I love when people dress against people’s expectations: nerdy guys in black double riders, rebels in conservative tweeds, young people dressed like older people, older people dressed in a younger person’s fashions, masculine people in feminine clothes, feminine people in masculine clothes, etc. When it comes to style, recognize that you can’t convincingly adopt someone’s wardrobe any more than you can mimic their manner of speaking (again, to bring it back to language). Pay attention to how other people use language so you can broaden your horizons, but allow your use of language to be natural to you. Good taste ultimately reflects something about you.

Rely On People And Stores: Over the years, I’ve come to know a few people who have developed remarkably tasteful wardrobes in a short period of time. Without fail, it’s because they relied on people with good taste. Some relied on the right tailors or merchants. Others had the advice of trusted friends. Whenever I have a question about a watch, I turn to Greg Lellouche, Mark Cho, or David Lane. When I want to get an opinion on a fabric for a bespoke project, I ask George Wang. Recently, I was wondering if I should get my polo coat made with machine- or hand-finished lapels. Given the very trad style, I turned to Bruce Boyer for advice.

Over the last forty or fifty years, fashion has gone through what I’ve called The Great Uncoupling. Instead of going to clothiers such as J. Press or Brooks Brothers for their entire wardrobe, people now buy socks from sock companies, jeans from jean companies, and untuckable shirts from untuckable shirt companies. I think this is a terrible development. There’s real value in going to a store with a point of view and working with merchants (or tailors) who can guide you towards better choices. Be cautious about trying to do this on your own. Be wary of MTO shoe companies that will sell you expensive shoes according to whatever wild thing you imagined while on hallucinogenic drugs. Or group order projects where people design things by committee. Find people who can help guide you towards a more tasteful, coherent wardrobe, especially if you’re just learning to use clothes as language.

Buy And Experiment: Ultimately, you just have to buy things and experiment. If you want to know whether tassel loafers or military surplus pants work for you, you can only consume so much visual media before you buy a pair and see for yourself. Fortunately, it has never been easier to resell things, either directly through platforms such as eBay and Grailed, or by going through consignors such as LuxeSwap and Marrkt. Sample slowly and let your experience guide you. When wearing new things, try to see what you like or don’t like about the style, so you can refine your taste and choose better purchases in the future. I wrote a post for Put This On once about how to build a wardrobe that allows you to experiment. Embrace this as a fun, lifelong process.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be seeking advice from people with impeccable taste on how others can develop a similarly keen sense of aesthetics. Some may take the Kantian perspective of The Dress Doctors or postwar menswear writers; others may take a more contextual approach. The common thread is that they are all culturally sensitive—people who read books and travel the world, and are voracious consumers of culture. Consider their advice as if you were asking a trusted friend with good taste.

I want to leave you with this excerpt from Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez’s wonderful fragrance book, simply titled Perfumes. In one of her chapters, Sanchez writes that she has met scores of perfume fanatics over the years. Through that process, she has come to know many of them, and believes that she can sketch out a general trajectory of the path many take when developing their taste in fragrances. When I read this book many years ago, I was struck by how closely it mirrored my experience with clothes. Perhaps you’ll also see yourself here:

Stage 1: Mother’s bathroom

Early adventures splashing on Mom’s Shalimar/ No. 5/ Miss Dior/ Tabu/ Your-Memory-Here with the bathroom door shut. Belief that Old Spice/ Brut/ English Leather is the natural odor that God has caused fathers to emit after shaving.

Stage 2: Ambition and naïveté

Either given a perfume by an adult or inspired to buy one at puberty: a sophisticated thing that embodies an unknown world of adult pleasures and/ or a cheerful cheap spray to wear happily by the gallon.

Stage 3: Flower and candy

Phase of belief that feminine perfume should smell flowery or candy-like and that everything else is an incomprehensible perversion.

Stage 4: First love

Encounter with moving greatness. Wonder and awe. Monogamy.

Stage 5: Decadence

An ideology of taste, either of the heavy-handed or of the barely there. The age of leathers, patchoulis, tobaccos, ambers; or, alternatively, the age of pale watercolors in vegetal shades. An obsession with the hard-to-find.

Stage 6: Enlightenment

Absence of ideology. Distrust of the overelaborate, overexpensive, and arcane. Satisfaction in things in themselves.

(photos via Tony Sylvester, Apparel Arts, University of Minnesota, Color for Men, Dressing the Man, Men’s Club, David Marx, Chaos, Aime Leon Dore, Savas, Canoe Club, J. Press, Prada, and Yasuto Kamoshita)