In 1936, the editors of Apparel Arts published “Permanent Modern,” a fourteen-page article introducing their vision for the ideal menswear store. The article spares little in details. Included are elaborate floor plans and descriptions of the materials that should be used for the architecture, fixtures, and display cases. According to the editors, things should look modern, but not “voguish modern,” as you want to catch the customer’s eye, yet also make the place feel inviting. They even specified the lighting and air conditioning systems (two whole pages were dedicated to that). Should the reader want to implement their vision, they included a directory for the contractors, suppliers, and equipment manufacturers who could help with the store’s construction.

The store they imagined was grand – something like a Saks Fifth Avenue, but solely dedicated to men. There were five retail floors, each dedicated to a certain class of items. On the first floor, you had accessories and footwear. Moving up, there were sport, prep, and university clothes; then high-end tailoring; and finally moderately priced attire and boy’s clothing. The basement floor was to be a club lounge with fruitwood furniture and a fully stocked bar. And at the top-most floor, there would be a penthouse restaurant with an open-air dining terrace. Apparel Arts’ editors imagined that the terrace could be converted into a skating rink in the wintertime, which could also double as a stage for showing clothes on live models.

Some of “Permanent Modern” is about the kind of retailing people found appealing at the time. The massive, almost imposing architecture that people associated with luxury and modernity. The other part is about the idea of being able to find anything and everything under one roof, so that a customer could have the kind of holistic shopping experience that has all but disappeared from today’s market.

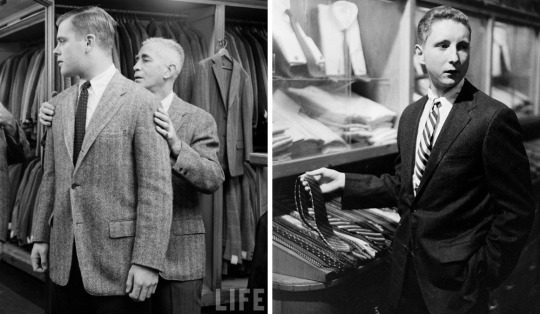

See some of these photos above. J. Press, a much more modestly sized boutique, used to sell everything a university student could want, from natural-shouldered blazers to rep striped ties to white buckskin shoes. Hermes, which started as a harness workshop in the Grands Boulevards quarter of Paris, stuck to their equestrian roots by selling horse-riding saddles alongside their square scarves and sac à dépêches. And before their stores were turned into pseudo-nightclubs, Abercrombie & Fitch used to outfit presidents and pioneers with hunting equipment and outdoorsman attire. It was a one-stop-shop for adventurers. Or, at least, men who fancied themselves as such.

These sorts of set-ups were not unique. Even French tailors David and Charvet, pictured below, sold more than shirts. A gentleman could have come into one of these shops in the 1920s and get almost anything he could want to wear with his new button-up – from gloves to pocket squares to socks. There were much more specialized stores (W. Bill was just a fabric merchant), but most places offered a range of products and services.

The biggest story today is about how the middle-tier of the fashion market is getting squeezed by fast fashion retailers and luxury brands. It’s hard for companies such as J. Crew to survive because their customers are splitting into two directions. Some are going up-market (for J. Crew, that may mean shopping at Sid Mashburn). Others are going downstream. Why pay more for flat front chinos, oxford button-downs, and plain colored merino sweaters when they’re so readily available at Uniqlo? It’s hard for middle-tier retailers to survive nowadays, especially if they have a large brick-and-mortar presence, because customers are constantly comparison shopping.

But there’s another change that I think is less recognized. Along with the death of these middle-tier retailers are clothiers who have traditionally been able to outfit men from head to toe. Before the war, retailing was somewhat consolidated by virtue of most men wearing the same things – dark worsted suits for work; more casual tailoring for weekends. After the war, as sportswear and designer clothing exploded, retailers became more specialized. You went to one shop if you wanted to create your identity around Italian suits and sport coats, another place for Levi’s and workwear.

Today, that uncoupling has gone even further. In the last 75 years, the production side of the global economy has become ever-more fragmented and decentralized. The New York Times had an article a few years ago about the 451 parts that go into making an Apple iPod. “Their study, sponsored by the Sloan Foundation, offers a fascinating illustration of the complexity of the global economy, and how difficult it is to understand that complexity by using only conventional trade statistics,” they wrote. “Ultimately, there is no simple answer to who makes the iPod or where it is made. The iPod, like many other products, is made in several countries by dozens of companies, with each stage of production contributing a different amount to the final value.”

That same kind of fragmentation is happening on the consumer side of the fashion market. More than just specialty shops for Italian tailoring and American workwear, we now have niche brands for every possible product. There are companies specializing in American-made raw denim jeans. A company just for shirts you can wear untucked. I once got a press about an upstart selling a specially formulated laundry detergent for men (because … regular detergent has girl cooties?). And traditional clothiers are having a hard time partly because of these companies – it’s death by a thousand cuts. As a friend of mine in the fashion industry recently told me, “a new brand nowadays has to fit their entire message into a Facebook tagline.”

It makes me wonder if all this is really better for the consumer. Instead of going to just J. Crew to get your entire wardrobe, now you have to sort through the list of companies specializing in just jeans or short-hem shirts. And then figure out how to combine these items into a coherent outfit, rather than rely on dedicated sales associates who can tell you what you need. Most of all, I wonder if we’re losing a bit of the magic and romance that comes with traditional retail. So many brands nowadays run on the appeal of transparency and efficiency – which, I suppose, is the only thing they can say about their single-product business. But for me, fashion is about a Ralph Lauren catalog and the idea that you can buy into a fantasy lifestyle with a new coat or accessory. What kind of lifestyle marketing can you really build around size nine cotton socks?