In the last few months, as millions of Americans have transported their work from cubicles to bedrooms, the US has engaged in something of a massive, unplanned social experiment. It’s estimated that up to half the US labor force now works from home. The other half is split between those not working and those still working at a jobsite (the second of which is mainly composed of essential service workers). Almost overnight, the US has transformed into a work-from-home economy coordinated through online applications such as Slack, Zoom, and Google Docs.

Now it seems that many companies may continue with this arrangement even in a post-COVID world as a way to save money. This summer, Facebook and Twitter captured headlines when they announced plans to let some employees operate from home indefinitely. Financial giants Morgan Stanley, Barclays, and Nationwide say they intend to do the same. At the moment, roughly 90% of Morgan Stanley’s 80,000 employees work from home, a process that CEO James Gorman says has been remarkably smooth. “We’ve proven we can operate with no footprint,” Gorman told Bloomberg Television. “Can I see a future where part of every week, certainly part of every month, a lot of our employees will be at home? Absolutely.” By the time the coronavirus crisis is over, we may emerge from our homes only to be told to go back inside again.

The opportunity to work from home has some obvious benefits: more time with family and pets, not having a stern boss peer over your shoulder, and being able to intersperse work periods with leisure activities (work at your own pace, so goes the theory). But when you check emails where you sleep and type where you eat, it’s hard to beat back the workday’s colonizing tendencies. Professors and freelancers know this all too well, as their constant-work culture deprives them of true leisure. When you never officially clock in or out, it’s easy to feel like you should always be using your time more productively, so you start to feel guilty for enjoying anything outside of labor. “I should be working,” says the nagging little voice in your mind.

Of course, this assumes you can tell the difference between working and relaxing. For many white-collar workers, the difference can be tough to define. We check emails; we type documents; we passively watch Sopranos clips on YouTube. These “non-activity activities,” as Shivani Radhakrishnan calls them, require such little exertion that it’s hard to tell when you’re actually laboring. “If work is associated with an initial amount of drudgery for a later benefit, we redefine leisure to mean an absence of such effort,” Radhakrishnan wrote in The Washington Post. “And when we can take breaks without ever stepping outside, it becomes easier to stay on the job longer, pouring more of our attention and energy into our work, and simultaneously, the market system. We get the appearance of leisure without really having it.”

It used to be that you could go to a library or cafe to get some work done, giving yourself a few hours to produce a document or answer emails. But with the necessary lockdowns and social distancing measures, that’s no longer possible. So, many of us are confined to our homes, where labor and leisure occupy the same physical and temporal space. We jump between Twitter and Gmail until the day passes, and the next one begins.

In the late 1960s, German sociologist Theodor Adorno wrote a critique of how capitalism structures our free time. We conceptualize free time as something that stands in opposition to labor, presumably so we can recharge and work all the more effectively afterward. “In a system where full employment itself has become the ideal, free time is nothing more than a shadowy continuation of labor,” he wrote. The short breaks we take while working from home — or living at work — aren’t real breaks at all, but instead brief pauses in a prolonged workday.

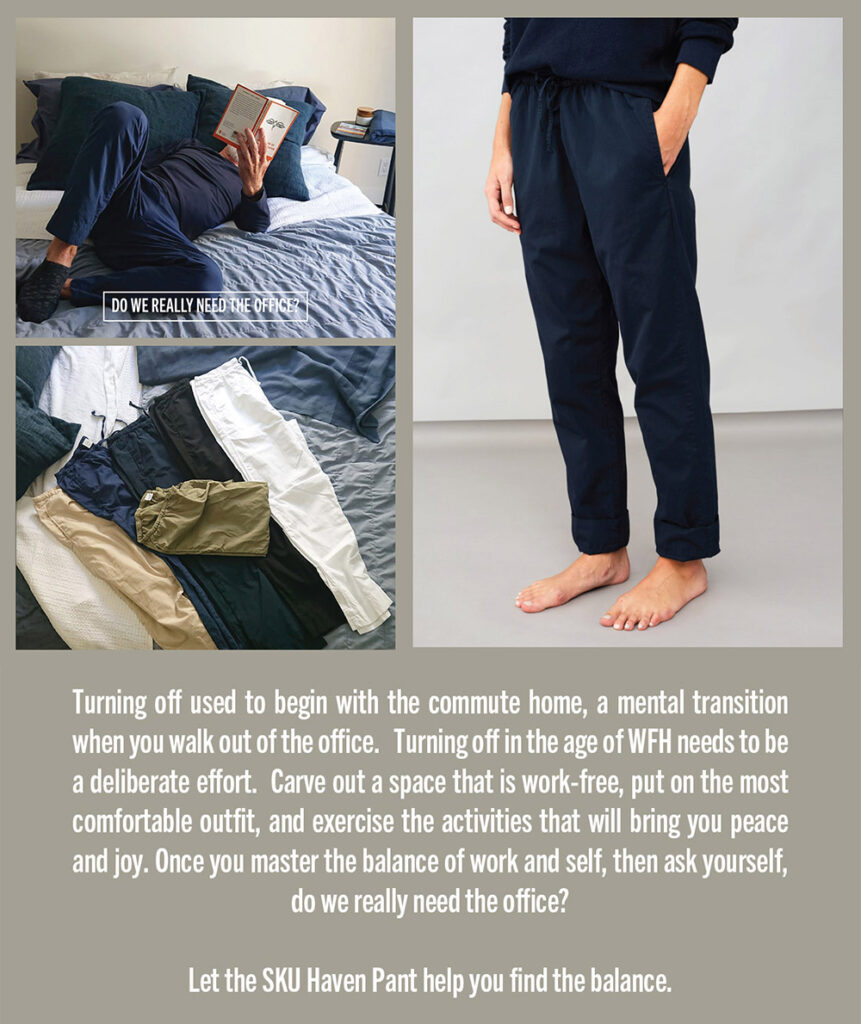

I was thinking about this the other day when I received an email from Save Khaki United (SKU), a contemporary American sportswear brand that focuses on streamlined basics. “Do we really need the office?” read the email’s subject line. “Turning off used to begin with the commute home, a mental transition when you walk out of the office. Turning off in the age of WFH needs to be a deliberate effort.” The email was a pitch for SKU’s new lounge pants, dubbed the Haven. These trim, tapered pants are made from soft, lightweight materials and feature a forgiving, elasticated waistband. I admit, they look nice, although I prefer the wider, more comfortable looking silhouette on A Kind of Guise’s “Samurai trousers.” My friend Kiyoshi, who’s located in Chicago, introduced them to me a few days ago over Blamo’s Slack channel (perhaps another small testament of our coming tele-community culture).

Neither of these pants, however, looks that much different than the leg coverings I’ve seen recommended for Zoom meetings, at-home workouts, and general lounging. In some ways, they’re just upgraded pajama bottoms. In the coronavirus age, we’ve been given a capsule wardrobe: one or two “presentable” shirts for online conferences, soft college-era tees, Patagonia Baggies, and elasticated easy-pants. Over at UNTUCKit’s website, you can find an entire section dedicated to wrinkle-free Zoom shirts for homebound people to wear for different occasions: Zoom meetings, Zoom happy hours, Zoom weddings, and what UNTUCKit calls Zoom Zooms (Zooms where you set up other Zooms). Like our leisure time, this feels like we get the appearance of clothing options without actually having any.

In an informal survey, I asked people on Twitter yesterday what best describes how they’ve been dressing at home. To be sure, the answers are probably colored by the season — people will naturally wear lightweight, minimalist clothing on days when it’s hot and humid. But the answers also weren’t terribly surprising. Nearly half of the 500 or so respondents said they wear things such as shorts, t-shirts, and casual short-sleeved button-ups. A quarter said they wear loungewear and pajamas; only fifteen percent said they wear something as formal as jeans and chinos. I didn’t have space to ask if anyone wears still wears tailoring, but I imagine very few do.

Irina Aleksander touched on this earlier this month in her brilliant New York Times Magazine essay, “Sweatpants Forever,” where she tells a broader story about the fashion industry through Scott Sternberg’s new leisurewear label, Entireworld. On the first day of the lockdown, Entireworld’s usual pace of selling 46 pairs of sweatpants per day skyrocketed to 1,000. Over the next two months, the company grossed more than it did in its entire first year in business. “In April, clothing sales fell 79 percent in the United States, the largest dive on record,” Aleksander wrote. “Purchases of sweatpants, though, were up 80 percent. Entireworld was like the rare life form that survives the apocalypse.”

American sociologist Richard Sennett instinctively knew this when he wrote The Fall of Public Man (1977), a history of public spaces and culture in and around New York City, Paris, and London in the 18th and 19th centuries. People dress for the public in ways that are very different from how they dress at home. Since clothing is about identity, and identity is performative, getting dressed in the morning is a form of ritualized production. For many people, fashion is a form of visual communication meant to be consumed by a passive audience. But without that audience, most people don’t truly get dressed. The body, as an object on which we place decorations, bridges the gap between the street and the stage. Sennett writes:

What makes 18th-century street wear fascinating is that even in less extreme cases, where the disparity between traditional clothes and new material conditions had not forced someone into an act of impersonation, where instead he wore clothes which reasonably accurately reflected who he was, the same sense of costume and convention was present. At home, one’s clothes suited one’s body and its needs; on the street, one stepped into clothes whose purpose was to make it possible for others to act as if they knew who you were. One became a figure in a contrived landscape; the purpose of clothes was not to be sure of whom you were dealing with, but to be able to behave as if you were sure. Do not inquire too deeply into the truth of other people’s appearances, Chesterfield counseled his son; life is more sociable if one takes people as they are not as they probably are. In this sense, then, clothes had a meaning independent of the wearer and the wearer’s body. Unlike as in the home, the body was a form to be draped.

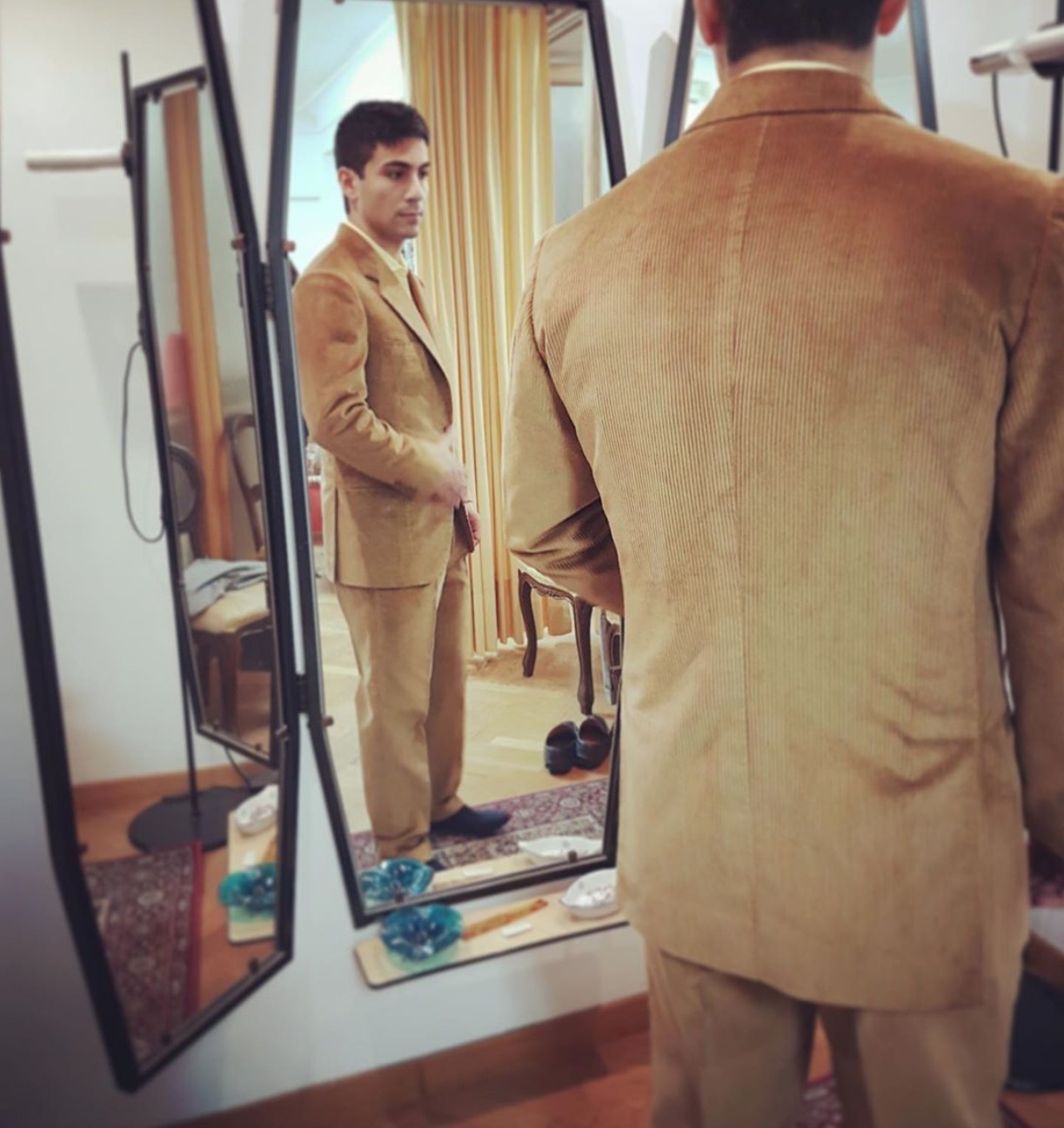

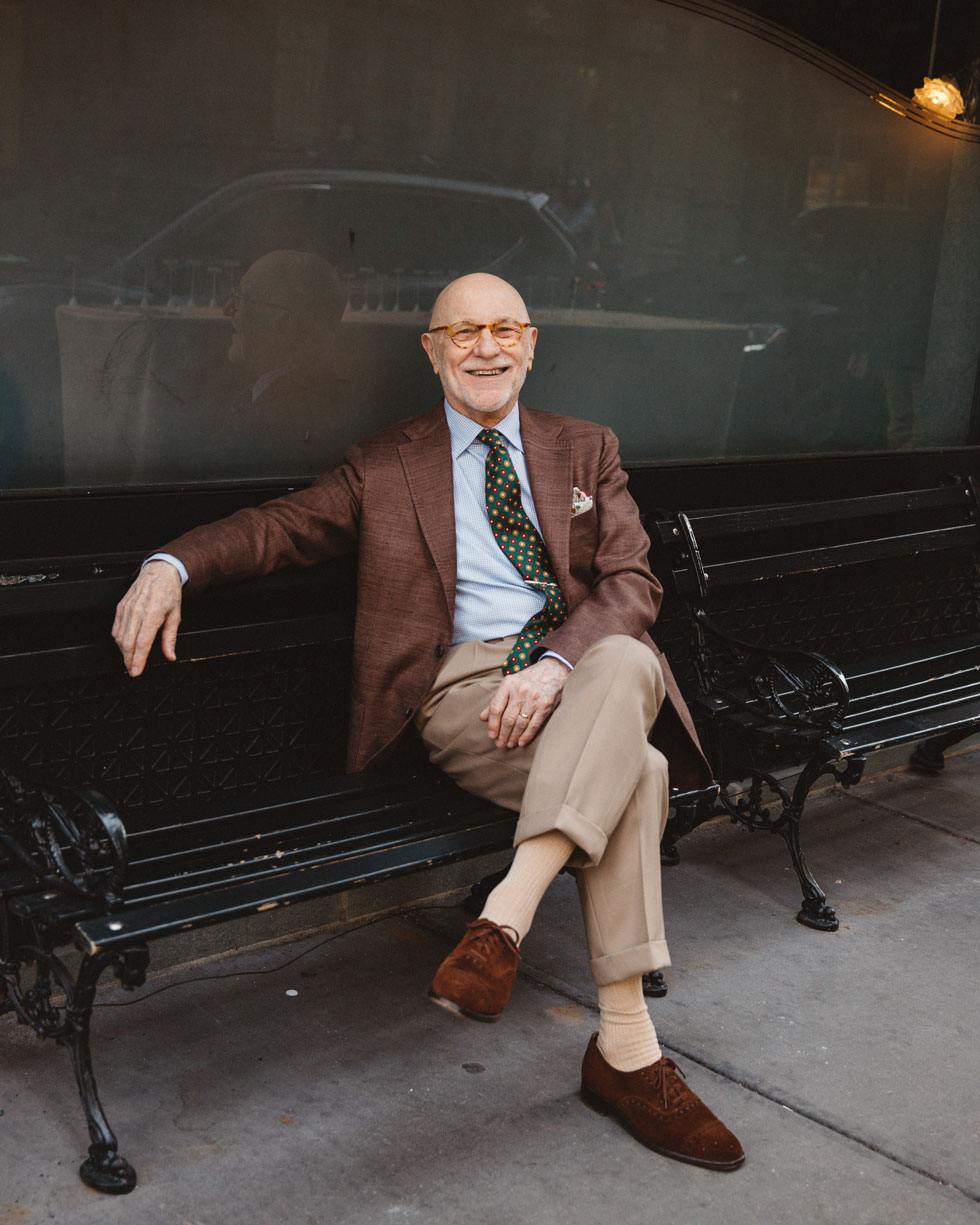

Of course, there are men who have been getting dressed — by which I mean, really dressed — at home and even under lockdown. Notably, many of them take selfies and post them on Instagram, which is to say that they’re still using their clothes to communicate something to an audience. However, while in lockdown in the privacy of our homes, most of us have been lounging around in t-shirts, sweats, and shorts.

Suit sales aren’t the only thing that’s down. According to market research firm NPD Group, denim sales have fallen by double digits in the last three months when compared to the same period last year. “Once the ultimate in comfort and casual wear, jeans have been usurped by more comfortable — and stretchier — options,” Abha Bhattarai wrote at The Washington Post. “White-collar workers who are logging in from home say they’re increasingly reaching for basketball shorts and yoga pants to pair with more professional-looking tops for video calls. […] Recent bankruptcy filings by the companies behind Brooks Brothers, Men’s Wearhouse, and Ann Taylor are an extension of that trend, analysts say, as Americans turn to less structured clothing for both work and relaxation.”

In the introduction to his 1859 book, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Karl Marx prophesied a post-employment society where men could freely dabble in fishing, hunting, and philosophy. “Society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow,” he wrote. Yet, nearly two centuries later, it feels like our lives have taken on a new kind of monotony. Work bleeds into leisure. Our homes have become our offices. We wear the same things for lounging as we do grocery shopping. If we’re still confined to our homes this fall, I wonder if we’ll even feel the distinctions between seasons.

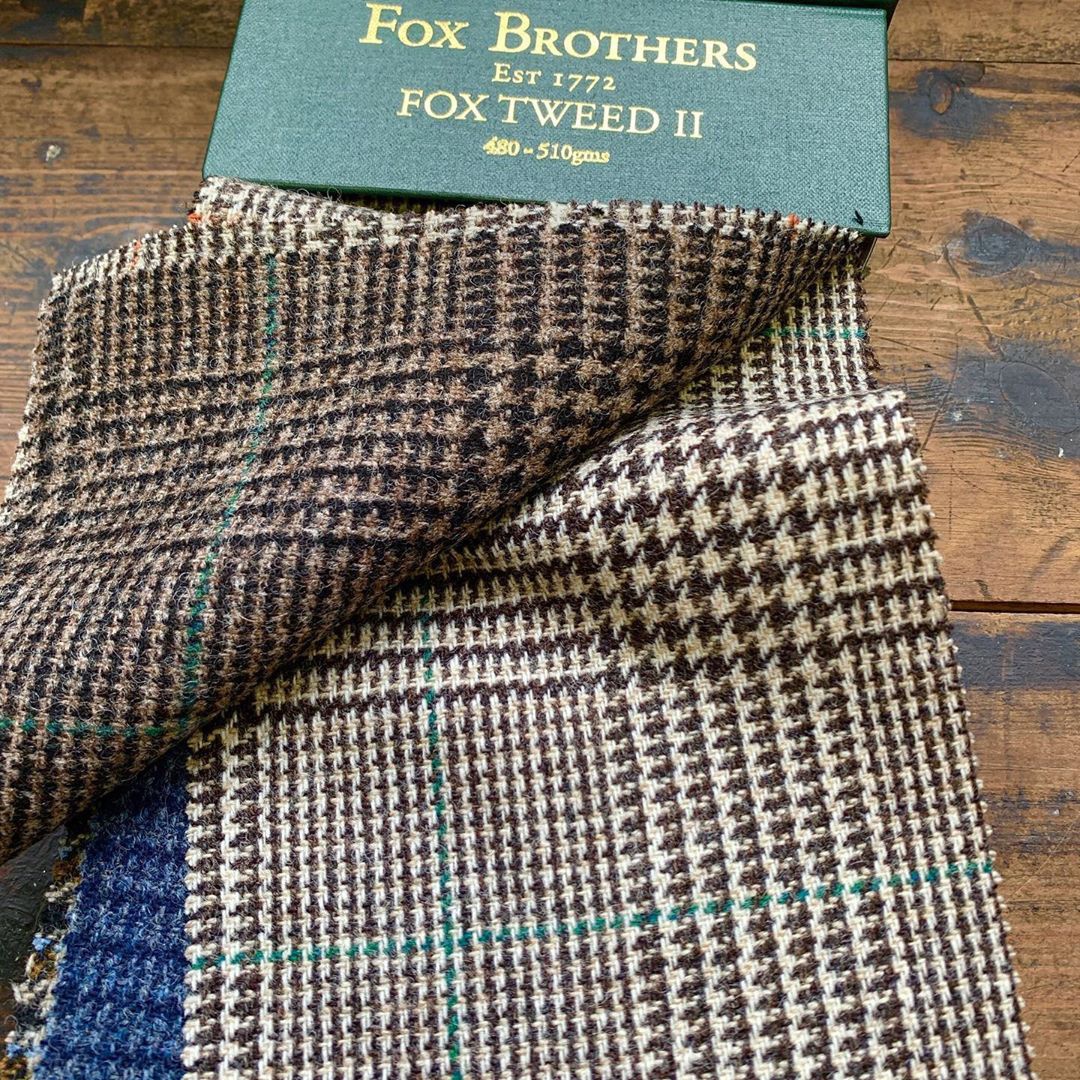

The other night, I got tired of wearing t-shirts and shorts all day. Eager to get out and walk a different course in my neighborhood, I put on a tobacco linen suit, light blue chambray shirt, and a pair of dark brown suede tassel loafers. I strolled along the main avenue near my home and passed by many businesses now shuttered — a dry cleaner, a bakery, and a mattress store (I don’t know how that mattress store survived even in good economic times, to be honest). I didn’t do much that night except get some fresh air, but it felt invigorating to wear something structured. There’s something special about the ritualistic act of wearing tailored clothing. Not only do you feel truly dressed, but “formal clothing” contextualizes casualwear. When you slip out of a tailored jacket and put on a t-shirt, the t-shirt feels lounge-y. But when you wear t-shirts all day, they don’t feel casual anymore — they’re just clothes.

To be sure, it doesn’t have to be tailoring. I miss all kinds of “outside” clothes that remind me of a life not at home — raw denim jeans, laced leather shoes, specialized field coats, leather jackets, and delicate sweaters that were far too expensive for my lifestyle (the kind of knits you’ll wear outside but never at home for fear of damaging them). But suits and sport coats draw the sharpest, most distinctive line between a life outside and the one spent at home, where an extended workday bleeds into leisure, and every activity feels the same. In the last few months, the lockdown has made me appreciate how good it feels to wear tailoring. Next time someone asks why I’m so dressed up, I’ll answer: “Because I’m outside.”