The hottest trend last year wasn’t the oversized puffer jackets, patchwork coats, or resurgence of lowbrow patterns such as tie-dye and leopard prints. Instead, the dominating trend of 2019 was the topic of sustainability. During the spring/summer seasons, major brands such as Ralph Lauren and Adidas capitalized on a growing consumer interest for eco-friendly products by releasing green polos and running shoes wholly made from ocean waste and recycled plastics. By autumn, Kering — the parent company to Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Brioni, among other big luxury labels — announced that it would commit to being carbon neutral across all of its operations. At the behest of French President Emmanuel Macron, François-Henri Pinault, the chief executive of Kering, also spearheaded an effort to get other major labels to do the same. Known as the Fashion Pact, the global coalition includes over 60 signatories, ranging from H&M to Hermes. They say they’ll make significant changes in their business to help meet science-based targets in three areas: achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, restoring biodiversity, and preserving oceans by reducing their use of single-use plastics. No punitive measures, however, will be imposed should they fail to meet their goals.

Of course, much of this comes as a result of the scrutiny the fashion industry has faced over its impact on the global climate crisis. There have been a lot of disturbing facts hastily thrown around, many of them not carefully checked. It’s often said that nearly three-fifths of the fashion industry’s annual production — estimated to be upwards of 150 billion garments — ends up in incinerators or landfills within years of being made. That results in about 10% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, more than the aviation and maritime shipping industries combined. As Vox noted, actual evidence for this is scant, although the fashion industry is indeed a mess. If anything, we know there’s too much clothing in the world by merely looking at our closets. Similar concerns have come up before, even if not directly about global warming. During the 19th century, as industrialization made things more affordable, many Europeans felt wonder and anxiety over their new material abundance. People worried about how to use goods well, what abundance might be for, and how not to be spoiled by possessions. Human virtues such as restraint and simplicity came to the fore, and some questioned whether the sheer quantity of objects around them would dull their senses.

When it comes to sustainability in fashion, discussions follow a very predictable course. The focus is often on tangible dimensions, such as build quality, materials, technology, transport, and recycling. In an interview on the podcast show Time Sensitive, Gabriela Hearst says her experience growing up on a ranch gave her a deeper appreciation for the calmness that comes with knowing that things around you don’t need to change, including the clothes on your back. “I really thought about why I am so attracted to things of quality,” she said. “It is because things have to be made well to last and to endure, so I grew up with things that were made to last and endure, not necessarily from an ostentatious point of view but from a quality, utilitarian aspect.” The only sensible and sustainable antidote to throwaway culture, then, is to purchase timeless, long-lasting clothing that you can wear for life.

Outside of fast fashion, however, most clothes do last. The problem with clothing is not that it disintegrates, but that it languishes in rag markets and landfills for years and years. Sustainability is about more than build quality; it’s about consumer behavior. In a product’s lifecycle (design -> production -> consumption), the weakest link is at the end. We discard things long before the end of their useful life simply because we become dissatisfied or disappointed with them.

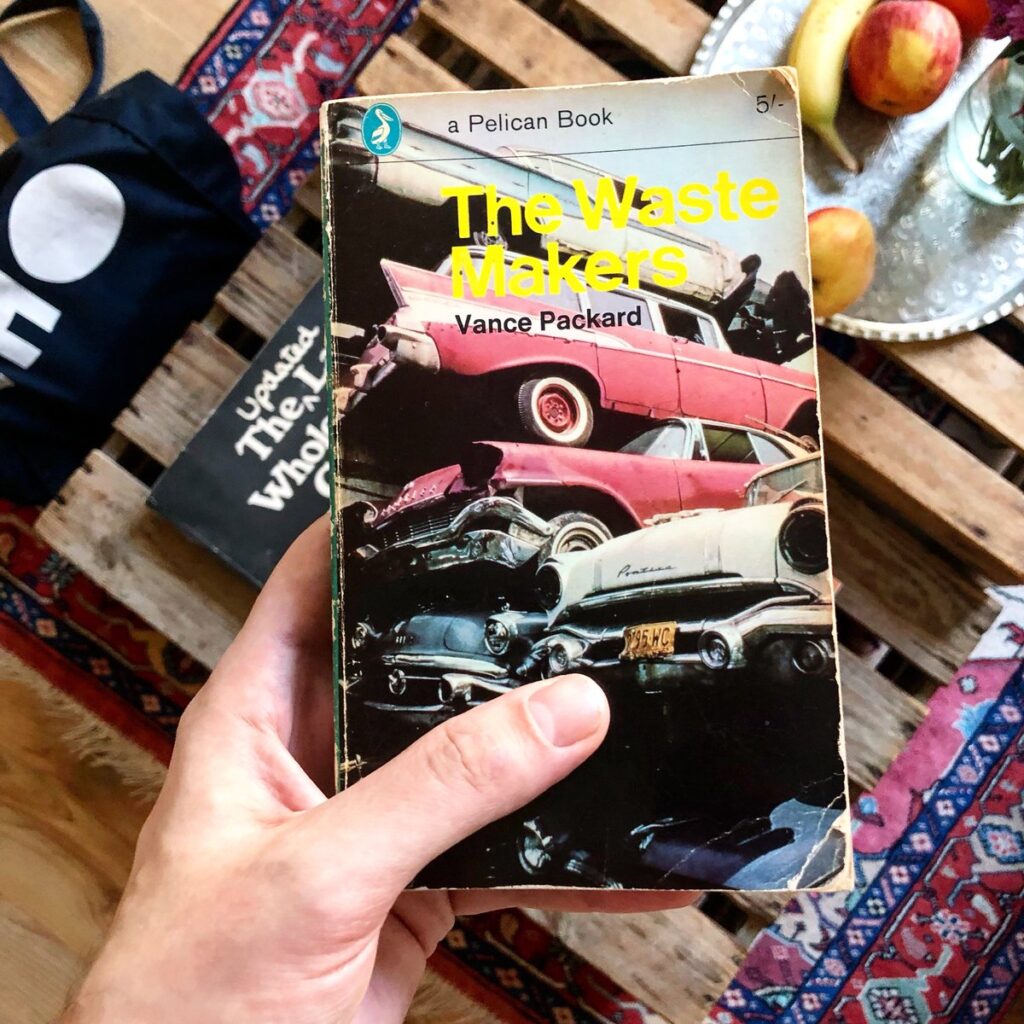

In his 1960 book The Waste Makers, American cultural critic and polemicist Vance Packard popularized the idea of planned obsolescence. He separated obsolescence into two categories: functional and psychological. Psychological obsolesce refers to the marketer’s attempt to wear out a product in the owner’s mind. The Waste Makers is influenced by Bernard London and Earnest Elmo Calkins, who wrote during The Great Depression about how to get Americans spending again. Packard, however, considered it unethical to deliberately shorten a product’s lifespan during normal economic times, as it results in wasteful consumer spending and devastating ecological impacts. How do you get consumers to replace perfectly fine items they already own? Introduce the new item as modern, which poses the older ones as out-of-date. This is the obsolescence of desirability, he writes:

Ideally, of course, it would be most satisfying to create this obsolescence in the mind by bringing out a substantially better functioning product. But in fast-paced modern marketing, there is very often little new that can be offered. The manufacturer can’t wait for the slow workings of functional obsolescence to produce something really better. Or he feels he can’t. So he sets out to offer something new anyhow, and hopes that the public will equate newness with betterness. Fortunately for him, mid-century Americans are prone to accept that equation.

The eco-friendly polos and running shoes that people so hurriedly went out to purchase may end up incinerators and landfills in a few years anyway because they got bored and want something new. No improvements in the production process can solve a problem that is fundamentally about consumer behavior. When people become bored with the familiar, they consume the unknown to demystify and familiarize. Then they become bored with those things and want to consume some more.

In menswear, we tend to think a lot about how something was made: whether shoes are Goodyear welted, a sweater is made from longer fibers, and a sport coat is fully canvassed. As the build quality goes up, it’s easier to justify an expensive purchase, as you can imagine wearing the item for years and years. To the degree we talk about design at all, it’s to say that people should eschew trends in favor of the timeless, minimalist, and versatile. But clearly, that’s not enough. Half the people who bought Aldens ten years ago are now wearing Hokas and Salomons. Piles of versatile, minimalist clothes languish in closets, untouched. The majority of garments that make up today’s second-hand markets and landfills still perform their job perfectly in the utilitarian sense — they cover your body and protect you from the elements. In an emotive sense, however, they bear some kind of immaterial defect.

More than just a garment’s physical durability, we have to consider its emotional durability. In his 2008 book Emotionally Durable Design, sustainable design theorist John Chapman stresses that “we are consumers of meaning not matter.” Emotional durability refers to a complex set of conditions that both drive and influence our material consumption, which really gets at the heart of sustainability. In a 2009 article published in the journal Design Issues, Chapman wrote:

The process of consumption is motivated by complex emotional drivers, and is about far more than just the purchasing of new and shinier things. It is a journey towards the ideal (or desired) self, that, through cyclical loops of desire and disappointment, becomes a seemingly endless process of serial destruction. Material artifacts may thus be described as illustrative of an individual’s aspirations and serve to define us existentially. As such, possessions are symbols of what we are, what we have been, and what we are attempting to become, and also provide an archaic means of possession by enabling the consumer to incorporate the meanings that are signified to them by a given object. Thus, consumers are drawn to objects in possession of that which they subconsciously yearn to become — the material you possess signifies the destiny you chase. In this way, it can be seen that products are not merely functional, but provide important signs and indicators of human relationships.

It’s hard to talk about emotional durability because it’s fundamentally about feelings and, thus, difficult to measure. But it’s much more directly about the lived experience you have with the objects around you. In some ways, it’s just another way of saying “buy less, buy better,” but it underscores that the most important dimension of quality is subjective and highly personal. Over at StyleForum, there’s a thread titled “The Contentedness Thread,” which isn’t so much about anti-consumerism as it is about objects that give us contentment — things that we wear and cherish, surprising combinations that provide us with satisfaction, and garments that simply imbue us with joy. The clothes in that thread stretch from the classic to avant-garde, expensive to affordable. It’s full of stories of people who are merely content with things they own.

As Chapman notes, until recently, “sustainable design methodologies seldom engaged with the more fundamental questions, such as the meaning and place of products in our lives, and the contribution of material goods to what might be broadly termed the human endeavor.” Discussions have to be pluralistic to improve on the lived experience with sustainability. While one answer is to be an ascetic, not all of us can turn our lives over to that kind of minimalism. It’s also not enough to tell people to escape from the trend cycle by purchasing whatever is deemed timeless, minimalist, or versatile. All too often, those terms and characteristics are just part of a new trend cycle. Instead, we need a more holistic approach to durability, one that considers an item’s physical and emotional resilience.

While Chapman and Packard only briefly touch on fashion, we can use their concepts to think harder about how to buy clothes we’ll eventually cherish. The most important thing here is that the process is deeply personal — you have to find what resonates with you. But here are some ideas on how to purchase things with greater emotional durability, which I’ve sketched out using Chapman’s concepts and my experience of building a wardrobe.

See Beyond the Physical: Fashion is fundamentally about semiotics. As Chapman notes, “we are consumers of meaning not matter.” The things in my wardrobe that I cherish the most tend to have a narrative or story. I love my father’s watch, which he handed down to me about ten years ago. I have a soft spot for the Lo Head look because I grew up with friends in that scene. I also really enjoy wearing certain clothes simply because I bought them from people I like — my Steed jackets, Nicholas Templeman shoes, 3sixteen jeans, and so forth. And there’s so much rich history behind classic men’s dress that I enjoy wearing certain things simply because of their stories. There’s something comforting about oxford cloth button-downs, Shetland sweaters, tweed jackets, classic leather shoes, and fisherman Arans. That comfort comes from more than just the clothes themselves.

Conversely, when clothes don’t go beyond the item you hold in your hand, I find the appeal can quickly fade. Sometimes that means the appeal was wholly about the price or value. Or it was about a new-fangled technological improvement in the fiber or construction. When the item is just about the physical object and nothing else, it’s easy to discover everything within only a few wearings. Then it becomes boring.

Learn to Empathize: In 1873, the German philosopher Robert Vischer introduced the word Einfühlung as part of his doctoral dissertation on aesthetics. The term, which was later popularized by Theodor Lipps, Freud’s admired philosopher, literally translates to empathy, but it means much more. It means “in-feeling” or “feeling into.” Vischer and Lipps propounded that a person’s ability to appreciate an object depends on their ability to project themselves onto that object. You have to enter the object and feel the emotions the maker worked to represent or imbue it with the relevant emotions. In this way, Einfühlung expands the concept of empathy from just our ability to share emotions with people to our internal capacity to engage with the world around us more deeply.

At a very basic level, clothes have to make you excited. You can review all their dimensions in rational ways — the materials, fit, quality, durability, and value — but if the garment doesn’t make you feel cool and stylish when you put it on, it’ll have little meaning in your wardrobe. “In their current guise, [most] consumer products lack the sophistication and layered complexity for this degree of long-term empathy to incubate,” Chapman wrote in his book. “Most consumer products relinquish their tenuous meaning to a single fleeting glance, while rarely delivering any of the life-altering rewards they so confidently promise. In this respect, waste is nothing more than symptomatic of a failed user/object relationship, where insufficient empathy led to a perfunctory dumping of one by the other.”

Buy Things That Age Well: It’s easier to cherish something when you like how the item looks from use and even misuse. However, this isn’t always possible and it depends on the aesthetic. Workwear wardrobes often look better as they get more worn-in, whereas dressier, tailored clothes can sometimes look better when they’re new. Suede, for example, picks up dirt and oil stains easily. On a rugged trucker jacket from Levi’s, you’ll welcome the patina. But on a dressier piece from Loro Piana or Cucinelli, you may be disappointed when you see a fresh stain and it doesn’t come out. When purchasing something, consider how the surface will change with use and time.

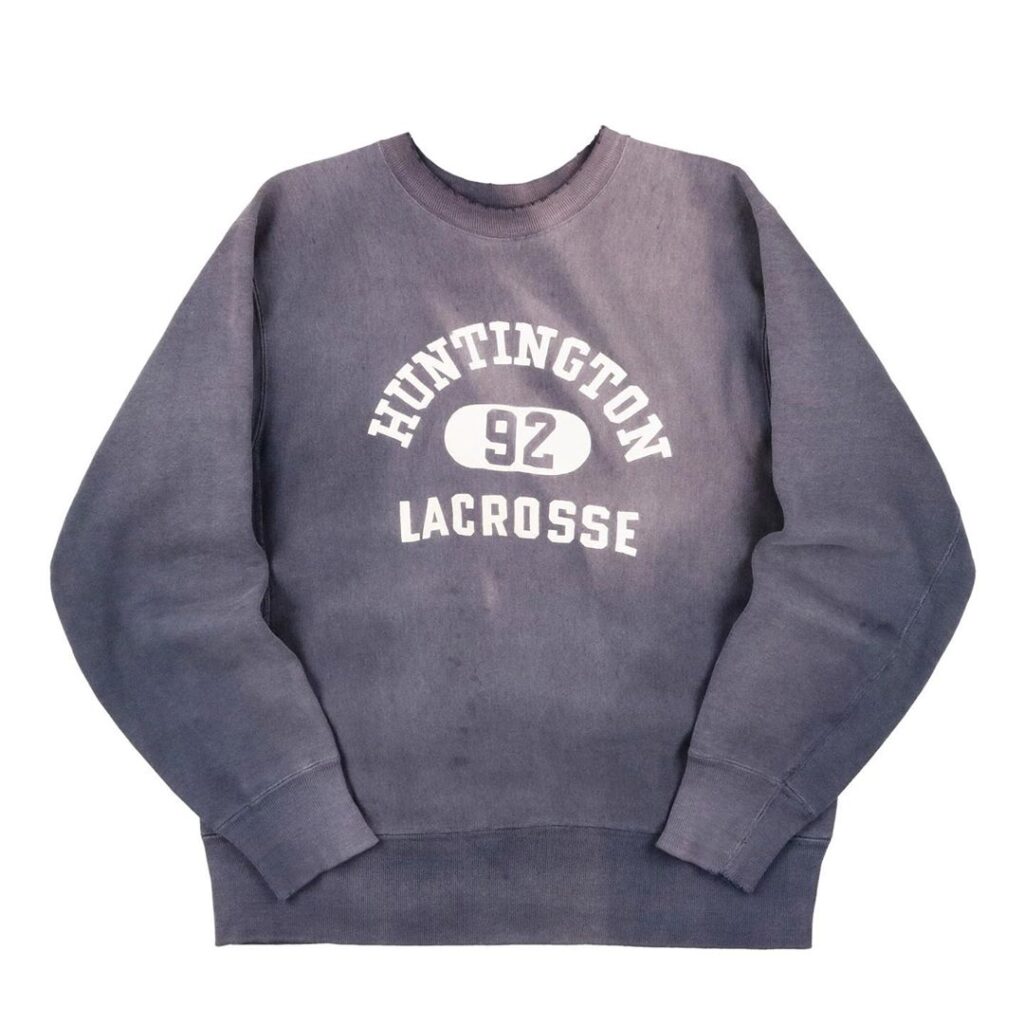

Build Attachment: Of course, if things don’t already come with layered complexity and meaning, you can create your own. One of the critiques of over-programming is that it doesn’t leave enough space to include the user’s psyche. When something has just enough space for your experience, you leave it open for chance discoveries, randomness, and intimacy. Object meanings can change significantly with use. You may love your old college sweatshirt because it reminds you of your time at the library, cramming for finals. Or you may enjoy a jacket because of how many trips it’s been with you around the world. The appeal of raw denim jeans — as stiff and uncomfortable as they can be at first — is that they’ll become psychologically comfortable once they become intimately familiar. When users share a personal history with an item — everything from the specialness of how it was acquired to how it’s worn and maintained — they’re less likely to throw it away.

Some objects are better than others in helping you build that connection. I like how you have to soak unsanforized denim, polish full-grain leather shoes, and brush out tailored clothing. Some people hate fountain pens because they can be high-maintenance, but I love them for the same reasons. Vintage fountain pens can leak, damage easily, and often don’t have a high ink capacity. Each pen can vary from nib to nib depending on how the pen has been treated over the years. However, that kind of quirkiness allows room for discovery. A Bic rollerball is boring by comparison. Chapman writes:

Fuzzy interfaces present users with complex, artful scenarios that must be learned and mastered — a novel departure from the unconsciously simple, spoon-fed manner in which interface design has become accustomed, toward a craft-like engagement in which the skill and mastery of an object must be acquired slowly, over time. Another advantage of fuzzy interactions is that they slow us down, creating what Ezio Manzini refers to as ‘islands of slowness’ that allow us to think, experience, and re-evaluate. The relationship between subject and object becomes evolutionary, as the subtle exchange of feed-forward and inherent feedback creates the illusion of mutual growth. Of course, fuzzy interaction is not for everyone, nor is it universally applicable. […] Nevertheless, alternative modes of interaction serve to remind us that perhaps the streaming of endeavors of modern times has inadvertently stripped the world of all its charm.

Set Realistic Expectations: Fashion is often marketed on the promise of transformative power. Consumers buy new clothes in cycles of desire and disappointment as they acquire things based on aspirations, only to realize that their lives remain unchanged. It’s important to realize that clothes only have so much potential and they don’t define you existentially. “Attachment may actually be counterproductive, as it elevates the level of expectation within the user to the point that is often unattainable,” Chapman warns. “When users feel no emotional connection to the product, they have low expectations and thus perceive it favorably due to a lack of emotional demand or expectation.”

Similarly, it’s OK to fall out of love with an item and move on. Even the love between two people — which is a richer two-way emotional exchange — can fade once the gloss of newness has worn away. “Indeed, the love between subject and object is often transient and is seldom eternal,” Chapman writes. “Then again, the same may be said of inter-human relations, which often portray equal degrees of instability and fragility that are not altogether different.” Some people are lucky enough to have found their style early, but I don’t think it’s necessary to stick to one wardrobe. That can be an unrealistic expectation that sets yourself up for disappointment. It also takes a few cycles of buying and reselling for you to hone your emotional antenna for clothing.

Ultimately, when things stay in our wardrobes, it’s about more than just whether they’ve weathered trends or physically endure. It’s about whether they make us feel as good today as they did when we first put them on. The challenge is moving from the honeymoon phase we have with every new item to the longer, richer, and more emotionally resonant period of cherishment. A couple of months ago, Rachael Tashjian wrote a piece for GQ titled “The Most Sustainable Idea In Fashion Is Personal Style.” “Personal style, not fashion, holds the greatest reward: it allows you to invest in yourself, rather than in a bunch of ideas about who you could or should want to be,” she wrote. “The wardrobe has somehow become the least considered part of fashion, in part because a lot of people you see in fashion are borrowing things rather than really owning and wearing and loving them, and in part because we have learned to love and rely on a culture of nonstop novelty. We’ve taught ourselves that our clothing can only bring a sense of joy the first time we wear it. But there are ways to train yourself to love something every time you put it on. The real test for me is: can I put it on, forget about it for most of the day, remember I’m wearing it at 4 pm, and grin? If the thing is really great — and I promise you this — people don’t think, ‘I can’t believe he’s wearing that jacket again.’ They think about how cool it looks on you — and about how envious they are that you have a signature, that you dress like you really know yourself.”