Menswear entered this coronavirus era while in the throes of no-holds-barred style. In the weeks leading up to the Bay Area’s shutdown order, I received a steady stream of emails promoting oversized suits, Gore-Tex hiking boots, and hallucinogenic tie-dye tees. But in even in the early days of the crisis, this veneer was starting to crack. In a Dazed interview published last December, Virgil Abloh predicted that fashion will soon move on from its obsession with streetwear and hype culture. “How many more t-shirts can we own,” he asked, “how many more hoodies, how many sneakers?” Could we be witnessing a return to heritage menswear, classic tailoring, and appreciation for craft?

This sentiment is popping up everywhere. At Business of Fashion, trend forecaster Li Edelkoort suggested that this crisis will “completely reset the way we produce, dress, and consume.” Designers will no longer make six collections per year, nor will consumers feel compelled to purchase everything they see. Anna Wintour hinted on CNBC this week that the pandemic could end the era of disposable fast fashion. On the other end of the price spectrum, Simon Crompton at Permanent Style believes that artisanal menswear will fare better than other areas in this industry. In his article, industry figures predicted that it will be less acceptable to flaunt your wealth in the future, so we may see a resurgence of high-quality, low-key menswear.

Cam Wolf summarized this viewpoint well in his GQ article last month. “The garish, maximalist designs of the past couple years that emphasized status through logos or obvious brand symbols, and were welcomed with open arms in economic boom times, will likely no longer fly,” he wrote. “Consumerism won’t grind to a halt, but as a point of comparison, think of how differently our $500 kicks look now compared to 10 years ago: blank-slate Common Projects gave way to loud-as-hell Balenciaga Triple S sneakers. Which might look a little weird these days.”

Welcome to #menswear 2.0, as Wolf called it. Pronounced “hashtag menswear,” the term refers to the Tumblr hashtag, where many men first learned about Goodyear welted shoes and Neapolitan tailoring ten years ago. Wolf suggests that we may see a revival of #menswear values, even if not the aesthetic. As streetwear recedes into the background, the contemporary minimalism in the last few years will morph into classically styled, understated clothes. The environmental concerns around wasteful consumerism will reemerge as an interest in made-in-America manufacturing. And after months of quarantine, perhaps some people will feel inspired to dress up again. “No one wants more of this loungewear bullshit,” said Michael Williams, founder of the influential menswear blog A Continuous Lean. “They don’t want to think about being home on a Zoom call. People want to think about when they can wear a nice jacket and go to an event or be at a nice restaurant again.”

There’s a certain logic underlying this forecast, which is a continuation of the narrative of what made classic men’s clothing popular nearly ten years ago. In 2008, the subprime mortgage crisis triggered a series of events that led to a broader financial crisis. Countless Americans lost their homes and savings, the financial system collapsed, and consumer confidence plummeted. As the theory goes, American men then changed their appearance as an unintentional, almost unconscious reaction to the changing conditions of national life. They reached back into their closet and pulled out those dependable classics that referenced time-honored traditions. Whatever they couldn’t find, they supplemented with new purchases.

“Clothes were prized because they were trend-immune and well-made enough to last through seemingly every style mutation,” Wolf explains. “Brands touted their heritage — a badge that proved they and their clothes had been, and would be, around forever. Customers wary about spending money on apparel justified purchases by convincing themselves they were buying for the long term.”

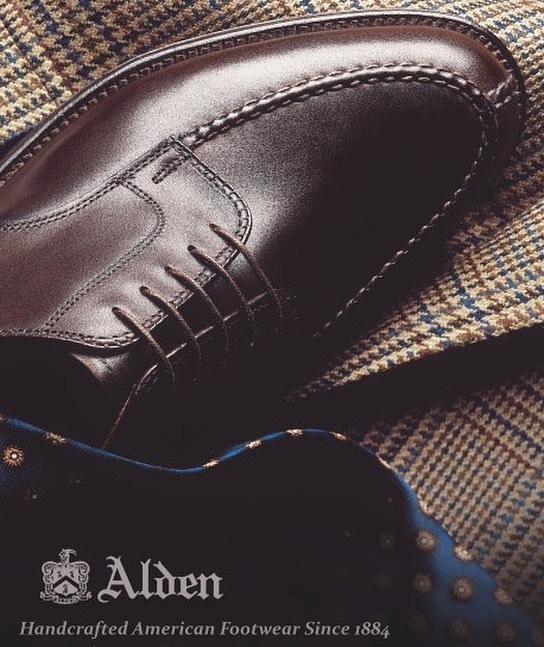

So goes the theory, anyway. While the 2008 economic crisis may have affected some men’s purchasing decisions, the heritage menswear movement was already happening before the housing market bubble burst. After all, people who just lost their job aren’t going out in droves to buy $500 Alden Indy boots and $150 Shetland sweaters. Instead, the original heritage menswear movement was an extension of the hipster movement. These two groups, which are seemingly opposites — one trend-averse and the other trend-obsessed — are just two sides of the same coin.

Guillermo Dominguez, a portfolio manager for New River Investments, came up with a good term a few years ago for the new economy he was seeing emerge out of his quickly gentrifying neighborhood. “The Quaint Economy,” as he called it, was one where businesses sell the story of how something was made, not really the thing itself. “It’s our desire to drink cocktails out of mason jars, rather than mass-produced glasses at Ikea, at a bar covered in reclaimed wood from a barn in Kentucky rather than something you’d find in the interior of a DMV.” It’s the consumer quest for all things “authentic” and “pre-modern,” conflating quality with nostalgia. The quainter the story, the better.

The term started as a joke in 2014, but it perfectly described an aesthetic that had been bubbling since the early aughts. The Quaint Economy is about artisanal products made for and by buffalo-plaid-wearing Millennials living somewhere in Brooklyn. Cynicism about corporations, modern life, and capitalism itself led many to seek “authenticity,” which often meant turning to the past for inspiration.

Although the show debuted on IFC in 2011, Portlandia also perfectly captures this ethos. While the show is named after Portland, Oregon, it’s really about the kind of micro-communities that make up (mostly) white, liberal cities — often places that shape a specific corner of popular culture. Portlandia affectionately pokes fun at people who take themselves too seriously, such as bike supremacists, eco-scenesters, bookstore feminists, gutter punks, and artisanal humans. One of the show’s recurring themes is about people obsessed with locally-made, small-scale, handcraft production. There are comedy sketches on farm-to-table restaurants, handcrafted light bulb makers, at-home picklers, Etsy jewelry makers, artisanal knot stores, and even raw denim enthusiasts.

Even before Portlandia aired, comedian David Rees was already parodying the artisanal movement with deadpan sketches about how to do simple things, such as opening doors, lighting matches, and tying shoelaces. In 2010, he published a hilarious guide on the lost art of pencil sharpening, titled How to Sharpen Pencils: A Practical & Theoretical Treatise on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening for Writers, Artists, Contractors, Flange Turners, Anglesmiths, & Civil Servants. It goes deep, and goes ridiculous, into the finer points of how to sharpen a pencil, such as how to shape graphite by hand and bag pencil shavings properly. For a period of time, Rees also operated a mail-in pencil-sharpening service and uploaded a series of “how-to” videos. I’m amazed that Rees can capture the tone and obsessiveness found in many “how-to” manuals and videos, while still maintaining an affection for that movement (which makes his satire good-natured and thus enjoyable).

The heritage menswear movement wasn’t just about craft — there was also a component in style. A few years ago, Frank Muytjens told me that he introduced Red Wings to J. Crew’s “In Good Company” section after seeing how lesbians were wearing them with slim jeans and plaid flannel shirts in Manhattan’s Chelsea district. What started as an identifiable uniform for urban hipsters and members of the LBGTQ+ community later became a mainstream look through retailers such as J. Crew and Steven Alan. Similarly, Mad Men inspired a whole new generation of men to wear suits again. And by the time Vampire Weekend was crooning about Cape Cod, there was already a cultural movement afoot to put men back in oxford button-downs and madras jackets.

It’s hard to overstate the influence of hipster culture. What was once derided as the ridiculous affectations of professionally idle people is now just how the world looks. In 2018, The Economist published an article defending the hipster coffee shop aesthetic. In the early 2000s, this would have been a description of a San Francisco cafe. Now it’s likely something near you.

The Starving Rooster is a trendy craft beer bar and restaurant in the middle of Minot, North Dakota, which is about as close as you can get to the middle of nowhere. Step inside though, and with its big wood tables, high ceilings, exposed masonry and industrial setting (it is housed in the former headquarters of a tractor company) it could be anywhere. Indeed, it is the kind of place you can find everywhere.

From Beijing to Bristol and Mumbai to Minsk, bars and cafes have taken on a similar aesthetic: tungsten-lit, warehouse-y spaces with lots of wood and brick, serving avocado on toast and kale-and-quinoa salads.

We commonly think of taste as being stable, personal, and rational. We like things because they’re good or because they’re a reflection of our true selves. Similarly, when people suggest that hard economic times will push men back into classic, dependable clothing, they assume people are driven by a rational calculation. But French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has a much better theory on taste.

In his 1979 masterwork “Distinction,” Bourdieu set out to show how taste is about signaling. Looking beyond the trappings of class warfare, Bourdieu showed how the battle for the right boots or hat was about competition in symbols, which reinforces class structure just as money does. The things you prefer often tightly correspond to measures of your social class: your profession, education, family background, etc. Taste is not stable. Instead, it’s strategic. Groups tend to disdain those closest to their social class — hence the term nouveau riche — and use different sources in taste to get a leg up. Bourdieu’s major contribution was in showing how people convert financial capital into “cultural capital” (his most famous coinage).

To be sure, not everyone interested in craft was influenced by the hipster movement. But the broader heritage menswear movement was an outgrowth of hipster culture. To understand what comes next will require a fuller view of culture, not just what’s happening in the economy. One of the important lessons from the heritage menswear movement is how popular culture is not binary. Instead, borders are porous, and influences are fluid. Fashion is a result not just of economic changes, but everything happening around us: music, movies, TV shows, politics, and food.

“There is a tendency to imagine the popular in terms of oppositions between high and low, vulgar and elite, center and margin, while ignoring the cross-fertilization that is itself a mark of the popular,” cultural studies professor Myra Mendible wrote in Bananas to Buttocks. “[Popular culture productions] create a spectacular ‘peep show’ where all of us can catch a glimpse of our various others and form identificatory bonds and affiliations.” Instead of thinking that fashion’s obsession with streetwear and hype culture will collapse and reemerge as its opposite — classic clothing and craft — we should identify what’s exciting about culture right now.

When I think about what’s important in culture right now, I think of people’s growing concern for the environment and their greater acceptance for non-traditional identities. I also think many men are finding that clothes can be a source of joy, rather than anxiety. Many are dressing according to emotions, not rules, and they’re unlikely to go back. The good news is that it’s never been easier to dress however you please. For men who enjoy tailoring and craft, those things will still be very relevant in the future. I imagine vintage will gain in importance and outdoor aesthetics will continue to be popular. Abloh is probably right, too. Streetwear will likely not survive.