In 1966, following his first successful art show, James Rosenquist commissioned a custom suit from fashion designer Horst. It was tailored from large sheets of brown paper, which the artist sourced from the Kleenex company. To be sure, this wasn’t the first paper garment. Women at the time were already wearing pleated paper dresses made from “Campbell’s Soup” prints, which were a perfect embodiment of the pop art movement Rosenquist helped pioneer. But his was the first of its kind in menswear. When he received his paper suit — pressed crisp and flat — he unfolded it, wrapped it around himself, and wore it everywhere. Rosenquist wore his paper suit to galleries and museum openings. He wore it to his art shows, where he met Very Important People, presumably while sounding like a crinkled lunch bag whenever he moved. The suit garnered him media attention, including an interview in New York Magazine.

Thirty years later, Rosenquist had a hundred more suits made through Hugo Boss. These were produced from Tyvek, a nonwoven synthetic material made from spun-bonded olefin fiber. Tyvek is mostly used to cover and protect construction buildings, but its thin, weblike structure also mimics the appearance and texture of paper. These suits were later sold to art collectors, and a small number were hand-signed. Today, they hang in museums and private estates, but if someone wanted to, the suits could also be worn and washed like everyday clothing.

Rosenquist’s paper suit combines utility with disposability. When he conceived the idea in the 1960s, throwaway consumer culture was starting to emerge. The disposable safety razor first found commercial success around this time, as did things such as disposable lighters and rollerball pens. Rosenquist’s paper tailoring, however, was surreal, not just because it’s visually strange, but because it transferred the idea of disposability to fashion. Who could have guessed that, fifty years later, disposable clothing would become our new norm?

Much has been written about the problems with fast fashion, but the blame is often misplaced. Fast fashion is seen as evil because it’s cheap and mass-produced. In menswear lore, there’s a familiar romanticizing of the world as it is imagined to have existed before industrialization and its ideological handmaiden, capitalism, got to it. Tailors once lovingly crafted clothes by hand, one-by-one for distinguished customers. But today they’re punched out of machines or made in dimly lit sweatshops for the unwashed masses.

The issues surrounding overseas production, particularly those that take place in industrializing nations, are complicated. China, of course, is the poster child of how a country can successfully use apparel manufacturing for export-led development. Paul Krugman, a famously liberal economist, once wrote an article at Slate praising this kind of cheap labor. “In a substantial number of industries, low wages allowed developing countries to break into world markets. And so countries that had previously made a living selling jute or coffee started producing shirts and sneakers instead,” he wrote. “Wherever the new export industries have grown, there has been measurable improvement in the lives of ordinary people.”

If it weren’t for these industrial jobs, so goes the logic, people would be living in more squalid conditions. According to UNICEF’s 1997 “State of the World’s Children” report, approximately 50,000 children in Bangladesh were laid off in 1993 in anticipation of US Congress passing the “Child Labor Deterrence Act.” The bill was designed to stop the importation of goods made with child labor. Left with no work alternatives or educational opportunities, many of these South Asian children turned to street hustling, stone crushing, and prostitution — all of which, the report notes, are much more hazardous and exploitative than garment production.

There are also plenty of examples of where apparel manufacturing has done very little to improve people’s lives. In 2016, economists Chris Blattman of the University of Chicago and Stefan Dercon of Oxford did a randomized trial study of industrial jobs in Ethiopia. Their study confirmed pessimists’ worst fears. Factory workers are paid low-wages and face high health risks (think toxic chemicals and dirty air). Contrary to expert assumptions, many job alternatives, which are often in agricultural sectors, are also not that bad. For many industrial workers, quitting their job for different employment opportunities is actually a wise decision. Vox gave an excellent summary of their study by saying globalization is complicated.

So perhaps the most fundamental takeaway is that we need to have a more nuanced picture of globalization’s effect on the global poor. Instead of thinking in binary terms, we need to separate out the ways globalization has benefited the poor versus the way it hurts them. Something as complicated as globalization is never going to be just good or just bad. We need to divide the good and the bad, and figure out how to address the latter without eliminating the former.

In any case, consumers are often in a poor position to know how their clothes were made. Even advanced economies have exploitative labor systems. The New York Times wrote an exposé last year on Italy’s shadow economy, an outhouse labor system that allows employers to pay workers very little in terms of wages and benefits (something menswear writers swoon about when breathlessly writing about the virtues of bespoke). Yes, $20 made-in-Bangladesh shirts are more likely to be made in poor conditions than $150 made-in-America button-ups. But notably, even after the collapse of Rana Plaza, humanitarian groups and labor organizations rallied for multinational corporations to stay in the country.

Simply put, export-led development, often through cheap apparel manufacturing, can be a way a country to get its citizens out of poverty. It’s the work of governments and large organizations to figure out how to regulate the economy to ensure better outcomes for everyone. This isn’t to say consumer groups aren’t necessary. Just that individual consumers are often doing little more than rehashing old unionist and nativist tropes when they say everyone should “buy American.”

The problem with fast fashion isn’t necessarily about its manufacturing. Or even it’s quality. Unfortunately, these clothes will languish in landfills and rag markets forever. It would be a boon if they would just disintegrate into dust like cynics assume. It’s also not about the price. Affordable, mass-manufactured clothes allow those who are economically strapped or simply disinterested to opt-out of the fashion system entirely, giving them a choice to spend their money on what’s important to them. The history of post-war style is also mostly about people who dressed well on a budget. Punks, spivs, wide boys, teddy boys and girls, beats and beatniks, modernists and mods, drags and dandies, hippies and bohemians, bikers, rockers, outlaws, and everyday workers show you don’t need a lot of money to look good. In fact, nearly every designer trend is just an upscale repackaging of an affordable look.

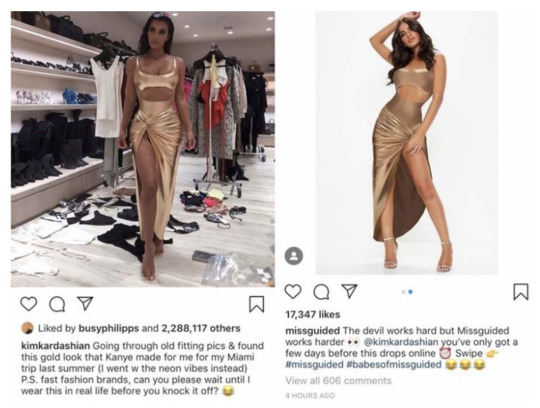

The real issue with fast fashion is about its design process. The “fast” in fast fashion refers to how quickly companies can bring runway looks to the market, turning rare pieces into the latest, hottest trends. Last month, Kim Kardashian won a $2.7 million lawsuit against the fast-fashion retailer Missguided. In February of this year, she posted a photo on social media of her wearing a shimmery gold Mugler dress. Kardashian begged companies to give it a second before copying it. “Going through old fitting pics & found this gold look that Kanye made for me for my Miami trip last summer,” she wrote on Instagram. “P.S. fast fashion brands, can you please wait until I wear this in real life before you knock it off? ?”

It took all of two hours for Missguided to come up with a similar look of their own. “The devil works hard but Missguided works harder @kimkardashian,” read their Instagram caption that featured the dress. Two hours. In less than the amount of time some people take to get dinner, a company collapsed the entire fashion cycle from haute couture to high street clothing.

Some will counter that this is good. Fast fashion companies democratize runway looks and turn rich people’s clothing into everyday apparel. But, in reality, these things are treated as disposable, much like Rosenquist’s brown paper suit. Before fast fashion, a runway look took years to cycle through the fashion ecosystem, going from designer to mid-tier, until it finally landed on the high street. Now, that cycle happens in a matter of hours. Fast fashion shoppers throw away their clothes after a year for a simple reason: the style is everywhere, which is possible only because it’s cheap.

To understand the fashion cycle, you have to go back to a 1904 essay on fashion by the German sociologist Georg Simmel. Simmel was writing when ready-to-wear was emerging. Fast fashion hadn’t yet been invented, and dress codes were still mostly governed by time, place, and occasion. Still, even at the turn of the 20th century, Simmel understood why fashion changes. People dress in ways to show their allegiance with some groups and opposition to others, as well as express their individuality within a chosen tribe. In other words, they typically dressed like their betters, which at the time fell along hereditary and class lines. Once the hoi polloi gets a hold of a look, however, the aristocracy moves on, thus driving fashion forward. As Simmel puts it:

Fashion is the imitation of a given example and satisfies the demand for social adaption; it leads the individual upon the road which all travel, it furnishes a general condition, which resolves the conduct of every individual into a mere example. At the same time it satisfies in no less degree the need of differentiation, the tendency towards dissimilarity, the desire for change and contrast, on the one hand by a constant change of contents, which gives to the fashion of today an individual stamp as opposed to that of yesterday and tomorrow, on the other hand because fashions differ for different classes – the fashions of the upper stratum of society are never identical with those of the lower; in fact, they are abandoned by the former as soon as the latter prepares to appropriate them.

Once someone walks out of Zara or H&M, however, it’s only a matter of hours before they notice everyone wearing the same thing. And of course, each of those people goes back to Zara for the new updated item, only to cycle through the same process. Unfortunately, this system affects everyone, including those who don’t even shop at such places. In a Business of Fashion interview with Cathy Horyn, Raf Simons spared no words when he called the current fashion industry model “bullshit.” “Technically, yes — the people who make the samples, do the stitching, they can do it. But you have no incubation time for ideas, and incubation time is very important. When you try an idea, you look at it and think, ‘Hmm, let’s put it away for a week and think about it later.’ But that’s never possible when you have only one team working on all the collections.”

He continues, “The problem is when you have only one design team and six collections, there is no more thinking time. And I don’t want to do collections where I’m not thinking. In this system, Pieter [Mulier, Simons’ right-hand man] and I can’t sit together and brainstorm — there’s no time. I have a schedule that begins every day at 10 in the morning and every, every minute is filled until the end of the day.“

Fast fashion isn’t the only reason why people cycle through trends so quickly now, but it’s an important part. If a brand rips off a jacket, it’s all but dead in a few months. Designers have to keep creating to stay ahead of the game, which speeds everything up and makes voracious consumers wanting more. When they’re not directly copying looks, they’re designing half-hearted mash-ups like the furry fleece double rider you see above. It’s a random combination of last year’s trends because no one at these companies has any time to think. This system creates more waste. Landfills wind up with clothes still with their tags attached because no one can be bothered to resell such cheap items.

It’s true that high-end consumers also buy much more than they need. Like an exploding volcano of cashmere and cotton, our wardrobes threaten to overtake our tiny apartments and bury us alive underneath piles of tailoring and tees. Everyone can benefit from a bit more thoughtful shopping. But I counter that fast fashion is distinct. For one, high-end clothes are too expensive for everyone to own, which is what allows them to hang around for a bit longer. Plus, high-end clothes are more likely to keep their value, allowing them to cycle through the second-hand clothing market instead of winding up in African rag economies. Fashion will always change because of our love for novelty and need to distinguish ourselves from others, but the current system is environmentally unsustainable and rotten to its core.

In the time that I’ve been writing about men’s style, I’ve given up on almost every dictum. I no longer think that everyone should spend a lot of money to buy quality, or that classic men’s style is the only way to build a wardrobe. I don’t think everyone should own a button-down shirt or pair of raw denim jeans. Style is so personal and expressive, which is what makes it interesting as a subject. The only thing I still stand by, however, is that fast fashion is evil. It’s one of the main reasons why rivers in China run blue with synthetic indigo. Mongolia’s once-lush grasslands have turned into deserts because of the ubiquity of cashmere. Even if fast fashion brands find more ethical ways of producing clothing, by speeding up the fashion cycle, they create a dismal environment for everyone – consumers, producers, and retailers alike – in the entire fashion economy.

So, what to do if you don’t have a lot of money to spend on clothes? The good news is that people have been dressing well on a budget for generations. Some tips:

Shop Vintage: Designers are constantly raiding thrift stores and clothing archives for inspiration, so why not just go directly to the source? Vintage stores are great places to buy stylish, affordable clothing. You just need to develop your eye. Clothes from the 1990s, admittedly, aren’t that great, but previous decades had well-made items in stylish designs. Flip through books about cultural movements to see how people dressed in the past. You don’t have to recreate those outfits, but getting a sense of what looks good can give you an idea of how you can remix things today.

Shop Second Hand: Relatedly, there are a ton of good options for buying gently used, high-end goods. StyleForum’s Marketplace, Grailed, The Real Real, Leffot’s Pre-Owned, Drop 93, Marrkt, Taylor Stitch’s Restitch, Patagonia’s Worn Wear, Etsy, and eBay all offer second-hand goods at less-than-retail prices. Over at Put This On, we do two eBay roundups a week for high-end menswear and send out an exclusive weekly newsletter to Inside Track subscribers (note, I work for Put This On). You can also try your hand at Yahoo Japan Auctions, which will have lower prices for Japanese designer brands. And many of these sites can be good ways to offload your unwanted clothes, helping you reduce waste and recoup costs.

Buy Good, Affordable Brands: There are plenty of good sources for affordable clothing. Nike, Hanes, Levi’s, Uniqlo, Dickies, LL Bean, Land’s End, Timberland, Carhartt, Vans, Converse, and Champion are all excellent, even if not top-tier. Nowadays, a garment’s design is more likely to give out than its construction. And these companies sell things that will look good for a very long time. This isn’t about hating things that are cheap, but rather hating companies that are ripping off high-end designers and speeding up the fashion cycle so no one has time to enjoy anything.

Organize Clothing Swaps: We all have things in our closet that we never wear, but are perhaps not worth the trouble of trying to sell. So, organize a clothing swap. “At the end of Articles of Interest, we organized a clothing swap where hundreds of people brought bags and bags of clothes,” says podcast host and producer Avery Trufelman. “They poured everything on the floor and everyone sorted through the pile to find things they wanted. The remains then went to Goodwill. It’s a great way to give clothes a second life, and you get to hear the backstory for a particular piece. Like, I picked up this crazy jacket that used to be owned by someone’s mom. It’s not something I would have ever bought in a store, but there’s such little risk at a clothing swap since it’s all free. It’s a good way to manage this feeling like you have to shop all the time. And this way, you end up experimenting more and expanding your style.”

Know What to Avoid: Fast fashion brands can rip off almost anything, but the styles that tend to cycle through the system the quickest are the ones that are easier to copy. Last year’s heavily pre-ripped jeans? Those come with an expiration date. My guess is that, by next year, skate-inspired, long-sleeved tees with the Online Ceramics-like prints going down the sleeves will look old too. Avoid cheap, easy-to-copy gimmicks.

Know What Can be Tailored: Not everything has to be form-fitting. Pay attention to how clothes can create different kinds of silhouettes and know when things can be altered. One of the most stylish people I’ve seen in real life is a young woman who works at a cafe I frequent. She wears oversized, vintage clothes that she alters at home with her sewing machine. Her style is tremendous — like a combination of Lemaire and Margiela, but somehow cooler. You don’t have to learn how to sew, of course, but if you can communicate what you want to a tailor, you can more easily build a better wardrobe.