For the truly fashion-obsessed, the shuttering of Gallagher’s Paper Collectibles ten years ago marked the end-of-an-era. The dingy, subterranean shop in the East Village was one of New York City’s greatest institutions. Inside was a veritable treasure trove of vintage fashion magazines, books, and photo prints. Stacked in corners and along shelves, you could find Vogue in all its editions, dusty issues of Harper’s Bazaar, 100-year-old copies of Town & Country, the now-defunct Mademoiselle, and more arcane titles, some of which were published in the 1860s.

If you think this is just a local hangout for art students and the occupationally hip, you’d be wrong. In between preparing for their seasonal collections, award-winning designers used to come here to rifle through yellowed pages and plunder archives. Michael Gallagher, the store’s proprietor, once told The New York Times: “We get them all, Hedi Slimane, Karl Lagerfeld, Marc Jacobs big time, John Varvatos, Narciso Rodriguez, the Calvin assistants, the Gucci assistants, Dolce & Gabbana, Anna Sui – you name it. They all come here for inspiration. At least that’s what we call it.”

It’s no secret that designers copy. Menswear is full of work, sport, and military references, some of which have carried through into a professional dress. Penny and tassel loafers entered the canon because they were so thoroughly imitated. In the designer world, Tom Ford has been known to lift from Halston; Alexander McQueen stole from Vivienne Westwood. Helmut Lang once moved his operation from NYC to Paris to thwart copycats, but he himself replicated a disco bag from the indie design collective Three As Four. Diet Prada tries to publicly shame designers for copying, but with notable exceptions, they have little effect. Everyone knows how fashion works. When Oprah asked Ralph Lauren in 2011 how he’s been able to keep designing for so many years, he answered: “You copy. Forty-five years of copying; that’s why I’m here.”

In fashion, inspiration can come from anywhere – other cultures and designers; archival collections; music, film, and art; and the sort of vintage prints and publications that you can find at Gallagher’s Paper Collectibles (the store supposedly reopened a few years ago on 12 Mercer Street, although I haven’t been able to get anyone to pick up the phone). Less recognized, however, is how common thrift shops, including ones in your hometown, have become the fashion industry’s engine for creativity.

People have been buying and wearing second-hand clothing forever. During the Elizabethan era, it wasn’t uncommon to see a charity shop somewhere in London, where a woman could pick up a gently used silk dress. The modern thrift shop, however, is a relatively new invention, at least in terms of how it exists culturally. Jennifer Le Zotte traces its history through her book, From Goodwill to Grunge: A History of Secondhand Styles and Alternative Economies.

The two main forces that gave us the modern thrift store are the same ones that shaped Western economic history – that is, the forces of industrialization and immigration. Industrialization and mass-manufacturing made clothing more affordable, which allowed people to treat clothing as disposable. And as more people flocked to urban centers, living spaces shrank, which meant that people had less space for storage. As a result, people were more likely to sell or donate their clothes once they became threadbare, rather than patch and repair.

As recently as the 1950s, however, there was still a social stigma attached to wearing second-hand gear. Part of this was about not wanting to look poor (my mother still doesn’t understand why I buy vintage when I can afford something new. When she was growing up in Vietnam, it was embarrassing to even wear hand-me-downs, let alone used clothes from a stranger). The other reason is more sinister. For much of the late 19th and early 20th century, people didn’t buy used clothes simply because they were largely sold through Jewish immigrants. Anti-immigrant and anti-Semitism meant that people commonly saw the “rag trade” as predatory and filthy. In an essay on how xenophobia marginalized the American waste and recycling industries, Carl Zimring writes: “The popular image of the junk dealer at the turn of the twentieth century was a hook-nosed, scheming Jewish immigrant bent on cheating honest American businessmen. […] Popular depictions of peddlers and dealers emphasized their ethnic dimension, linking ethnicity to unscrupulous behavior.”

Many people at the time didn’t even want to wear clothes that had at one point been touched by a non-white person. For example, during the Jim Crow era, African Americans were barred from trying on clothes in department stores, as it was believed they’d “defile” them (in his book, Minding the Store, Stanley Marcus, CEO of Neiman Marcus, talks about how he was one of the first to not only racially integrate his shops, but also push for desegregation in Dallas, a move that cost him customers). Similarly, some people didn’t want to wear clothes that had been handled by a Jewish person. In the spring of 1884, The Saturday Evening Post ran a satirical story about how a girl contracted smallpox because she bought a dress from a Jewish-owned resale shop.

There was real money in the thrift business, however. Christian ministries funded their outreach programs by selling donated clothes. The Salvation Army and Goodwill paid poor people in food and lodging in return for them going around with a pushcart to collect unwanted, used gear, which these organizations would later sell to others (often newly arrived immigrants who relied on such shops as their first step towards “Americanization”). At some point, the terminology changed as well. Once considered “rag dealers” and “junk shops,” these businesses eventually came to be known as “thrift stores,” which allowed middle-class housewives to “feel virtuous about buying something new because they could now give something back.” The world of second-hand shopping had finally linked the two Protestant ideals: charity and capitalism.

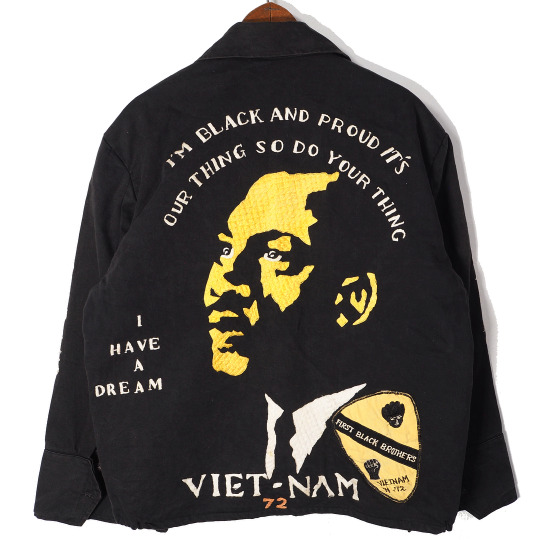

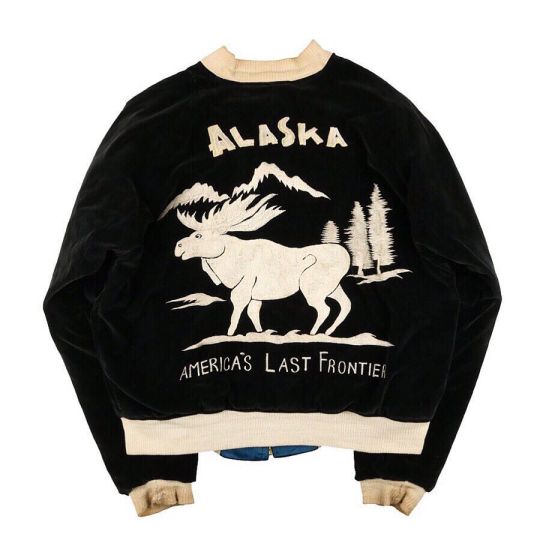

It wasn’t until the postwar period, however, that second-hand goods became chic. Consignment stores started catering to a higher-end clientele as wealthy and middle-class shoppers wanted to get better deals on couture. By the 1970s, shopping second-hand wasn’t just a matter of practicality, it was counterculture cool as people raided thrift stores for military surplus and workwear. Suburban garage sales became common and environmentalists encouraged people to buy second-hand. The Japanese at this time were also scouring thrift stores and flea markets for vintage Americana. As certain pieces became widely coveted, prices soared, making second-hand clothes not for the poor but the wealthy. From David Marx’s book Ametora:

Vintage stores gave disenchanted denim customers a chance to return to superior old models of Levi’s, Lee, and Wrangler. But the huge increase in demand drove up prices dramatically. In 1983, Harajuku’s Banana Boat charged around $237 in 2015 dollars for 1960s model Levi’s, but at the end of the decade, the store showcased its deadstock Levi’s in glass cases tagged at $1,390. The promise of enormous profit margins then triggered an in-flux of Japanese buyers to the United States. Before leaving for America, young recruits received training on how to appraise denim through minute features. The most telling symbol was the akamimi “red edge” on the inside cuff – a reference to the red line on Levi’s hems made before 1983.

By the late ‘90s, thousands of Japanese entrepreneurs joined the used clothing game. The original fifteen or so Harajuku shops faced growing competition from over 100 other second-hand stores in the neighborhood. Across the country, there were an estimated 5,000 stores specializing in used American clothing, a sector ranking in the hundreds of millions of dollars a year. The scale of operations grew so large that the major Harajuku outlets organized their overseas pickers into veritable armies. One Japanese store rented an apartment in Illinois to house salaried employees who would drive around the Midwest seven days a week and buy ten cartloads of old clothing at a time.

From Japan’s obsession with vintage Americana, we get much of today’s menswear culture – the focus on raw denim, selvedge stripes, loopwheeling, chainstitching, and runoff stitching all traces back to guys who scoured thrift stores and deadstock archives for old clothes (a topic that Marx brilliantly documents in his book). As Marx writes: “Japanese parents fretted that the boom in used American clothing revealed a morose recessionary mindset after the end of the Bubble Economy. But the youth themselves could not have disagreed more. Old American clothes were not symbols of impoverishment, but a sign of cultural and economic progress. Nothing was more real, more American – and more expensive – than an actual pair of 1950s Levi’s 501XX.” Our obsession with “authenticity,” no matter how vague the concept, means that vintage clothes today carry cultural capital.

This shift also means that the retail landscape today is richer than ever before in terms of preserving fashion history. Every flea market, thrift shop, and consignment store has become a mini-museum for fashion artifacts, including those made in recent memory and those from many generations ago. This has made the common thrift shop the industry’s engine for creativity, helping to rechurn and recontextualize old trends.

This dynamic is most obvious when you look at how designers rummage through second-hand stores to look for inspiration. Hiroki Nakamura, Frank Leder, Martin Margiela, Nigel Cabourn, and Emilie Casiez have all been known to borrow from the past (Casiez is often pictured on Instagram going to some very cool vintage markets). J. Crew’s higher-end Wallace & Barnes subline is inspired by the vintage pieces that Frank Muytjens and his team once collected for the company’s design archives.

There’s also that story of how Miuccia Prada, head designer of Prada and the founder of its subsidiary Miu Miu, once found a stunningly beautiful, silk faille Balenciaga coat with a rosebud print inside a Parisian vintage shop. Engrossed by the construction, she turned the seams inside-out and admired the detailing. When her friend suggested she should get it, Prada replied: “Oh, I’m not just going to get it. I’m going to copy it.” This is Miuccia’s genius – to be able to unearth the one thing in a vintage shop and know it will be a commercial success. Then to be able to copy it exactly.

Designers also copy in not-so-direct ways. The bell-bottoms craze of the 1960s and ‘70s started with women raiding their local thrift stores for naval uniforms. British and American sailors at that time wore bell-bottom cuffs so they could roll up their trousers while swabbing a deck. Counterculture types, however, knew they could wear the same pants to razz their parents, honor the working class, and strike a bohemian pose. By the time Sonny and Cher donned them on their popular TV show, bell-bottoms had entered mainstream fashion – not because everyone was shopping at thrift stores, but because designers had copied street culture.

The same dynamic plays out today with Hedi Slimane, Demna Gvasalia, and Martine Rose. All three are designers who heavily lift from street culture – including from people who originally got their fashion from thrift stores. In an interview with The Fashion Law, Courtney Love said of Slimane’s Saint Laurent’s collections: “The girl in the brown coat says it all. I love it. It reminds me of Value Village. Real grunge. I love that rich ladies are going to pay a fortune to look like we used to look when we had nothing.”

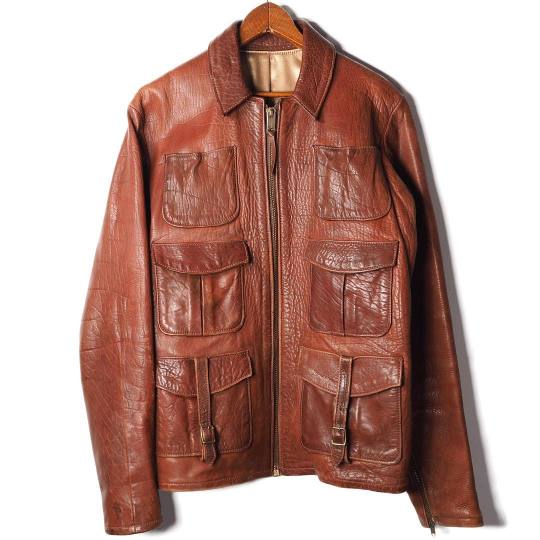

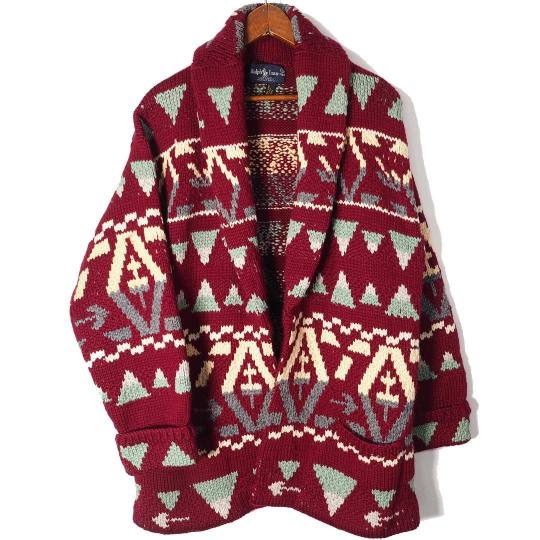

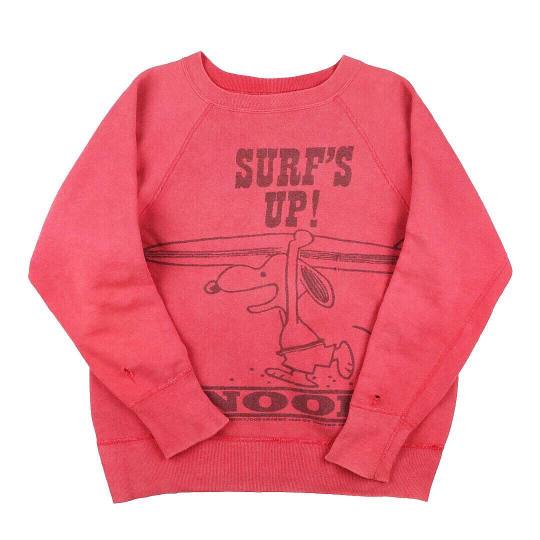

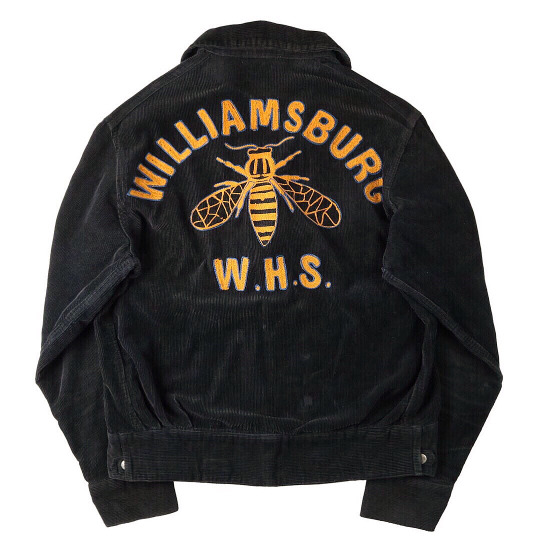

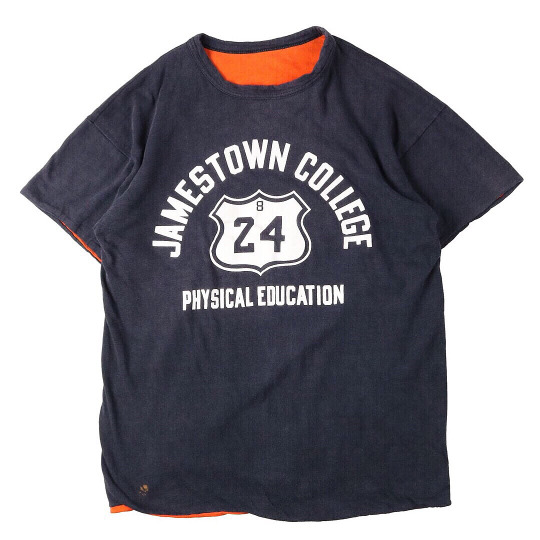

Shopping vintage isn’t just a smart way to save money, it can also be a way to improve a wardrobe. I particularly like French chore coats, military field jackets, denim truckers, OG-107 green fatigues, thick belts, and silver jewelry. Don’t be shy about checking out your local thrift stores and consignment shops – many of today’s designer pieces are just riffs on old pieces anyway. Online, I like browsing Wooden Sleepers, Canoe Club, imogene + willie, Etsy, and Put This On’s Shop (note, I write for PTO’s blog, although the shop is a separate operation). Acorn Vintage, Brut Clothing, Saunders Militaria, and Fort General Store on Instagram are also great for ogling.

(photos via Brut Clothing, Wooden Sleepers, Emilie Casiez, Acorn Vintage, and Fort General Store)