No Man Walks Alone Anniversary Sale

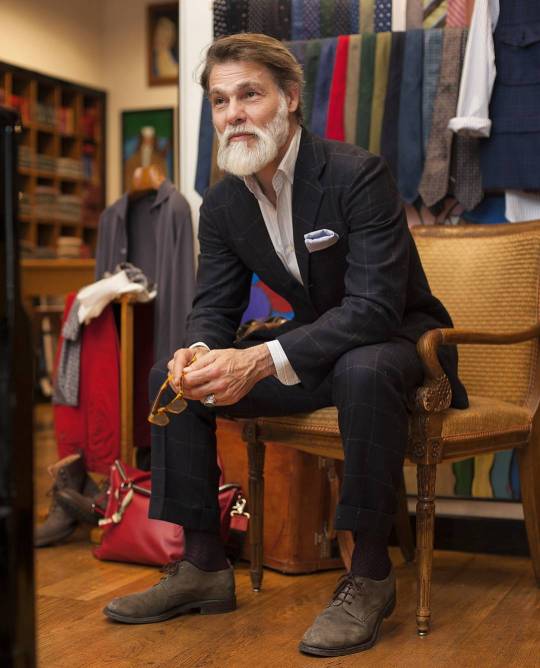

Six years ago, Greg Lellouche called me to say he’s starting a new online store called No Man Walks Alone (today a sponsor on this site). I remember being excited about it because Greg has a uniquely open-minded view on men’s style. Even today, most shops are singularly focused on prep, workwear, or the avant-garde – they push a very specific look. No Man Walks Alone mixes all three in a way that feels natural.

In a recent interview at Handcut Radio, Greg says he thinks streetwear has had a positive influence on menswear, at least on balance. “I like how streetwear has liberated men from the idea of a uniform. They can wear crazy printed pants with an old sweatshirt from high school and not feel ridiculous about mix-and-matching different perspectives. By broadening the scope, it’ll eventually trickle down to a mainstream way of dressing, and it’ll bring a bit more freedom and individuality to men’s style.” That open-mindedness probably explains why you can find everything from Italian tailoring to Japanese workwear to the avant-garde at his shop.

To celebrate their sixth anniversary, No Man Walks Alone is offering a 20% discount if you use the checkout code sixyears. The promotion is running until this Tuesday, October 22nd. Here are nine things in the store I’ve been admiring.

Keep reading