Over at J. Crew, you can find over fifty shades of grey, ranging from “obsidian” to “vintage dove.” The company describes their granite-colored Ludlow suits as “coal,” but that color shouldn’t be confused with the cooler, stone-like shade of their 9" tech shorts, which are also labeled “coal.” Neither of those should be mistaken for J. Crew’s “Bedford coal,” which is different color entirely. In the past, the Americana outfitter has used all sorts of exotic names to describe very ordinary colors. There’s been “dried fig” (green), “surplus grass” (also green), “natural kale” (again, green), “spearmint sprig” (once more, green), and “fresh water” (blue). Reading through these colorful words, you’d struggle to know whether you’re scanning a J. Crew catalog or a farm-to-table menu at a hip Brooklyn bar-restaurant.

To help eliminate the confusion, some people have tried to standardize the ways in which we describe color. Albert Henry Munsell devised a three-dimensional mapping system for color in the 1880s. A. Maerz and Mr. R. Paul built on Munsell’s work but also incorporated common names for various hues and shades. They published their book A Dictionary for Color in New York in the 1930s. Across the pond, the British Colour Council produced a series of color indices from the 1930s through the ‘50s. Their first book, a two-volume set titled Dictionary of Colour Standards, was published in 1934. The Council hoped that it would do for color what “the great Oxford Dictionary has done for words.” The book “would mark,” they wrote, “the great achievement of modern times in assisting the British and Empire industries with colour definition,” thereby giving the British trades a competitive edge.

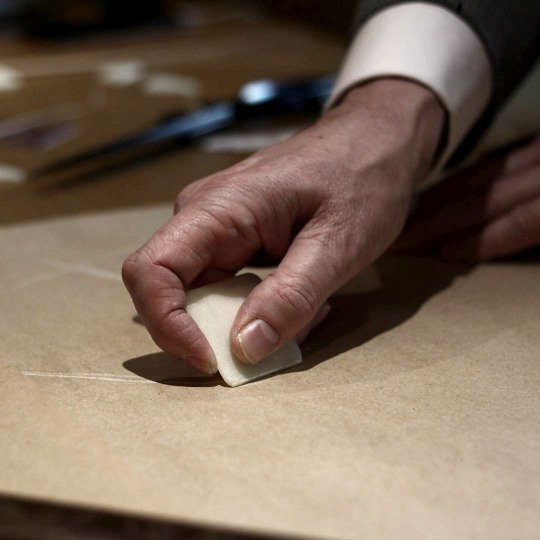

Shortly after the book was published, The Dictionary of Colour Standards was used as the official reference everywhere from the Royal Horticultural Society to the British Army to the Royal Institute of British Architects. Dermatologists, art curators, and map printers relied on the dictionary to produce important documents. Part of their success was due to the fact that they labeled every printed plate with an evocative name and reference number, much like you’d find in a Pantone guide. They also included fabric swatches for textile designers. Chartreuse, after all, registers sightly differently on paper than it does on fabric. So for the first edition of their book, the Council included carefully dyed silk ribbons. The follow-up edition, released in 1952, came with woolen yarns.

Keep reading