Men’s style has been primarily confined to simple lines and sober colors since the days of Regency England, but the summer shirt remains one of the last places where you can still wear a bit of pattern and color. In the 1960s, shortly after Hawaii attained US statehood, mainland Americans wore Aloha shirts for the freedom they represented: a warm island life far away from cold factory work and steel offices, where you could be serenaded by ocean waves and fall asleep on the beach. Somewhere along the way, the dream got corrupted. Colorful, printed shirts, particularly those in oversized, short-sleeved form, have become the style signature of guys with outsized personalities: golfing uncles, Guy Fieri, and Smashmouth fans.

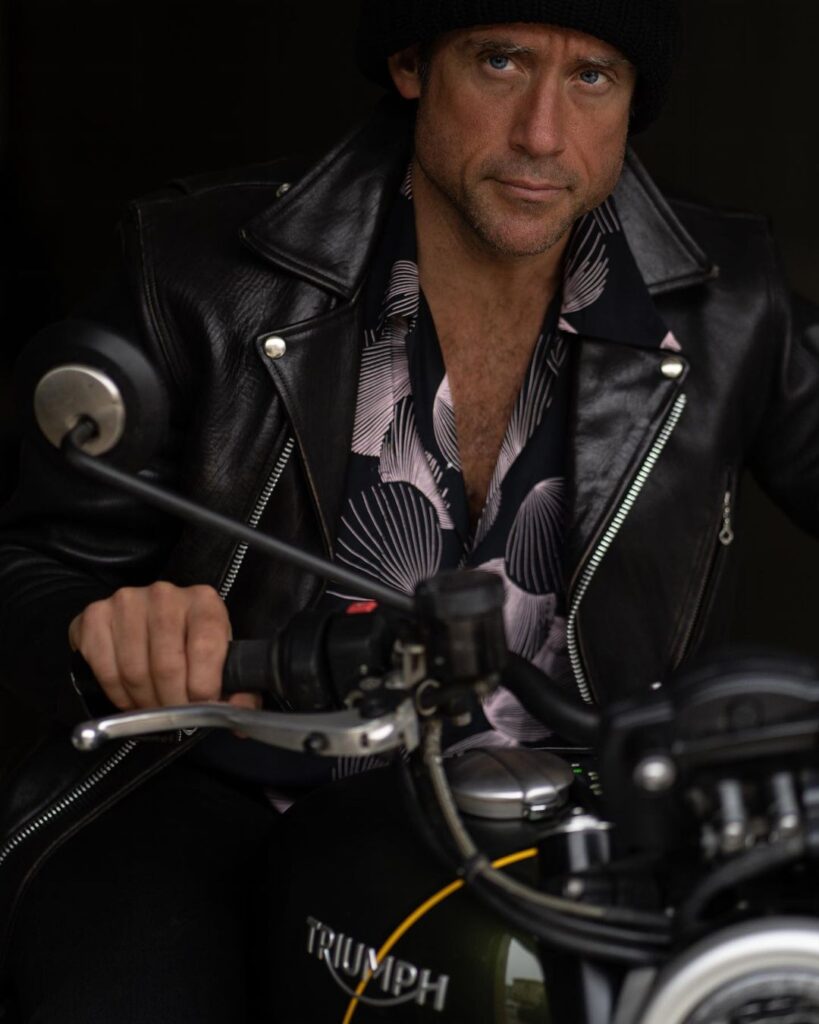

In the last few years, the summer print has started to come back in earnest. Luxury brands such as Prada and Saint Laurent have used them in their darker-themed runway collections. A little sleazier and more LA-inspired, these feel more like Scarface than “Margaritaville.” There are also upbeat designs that take inspiration from Hawaiian history, surf culture, mid-century design, leisure activities, and resort wear. For some, these outlandish shirts are little more than wearable postcards. For me, they’re a sign of positivity. I’m dreaming of wearing a printed shirt this summer with shorts and huaraches, like Donald Glover above, while listening to The Delegation’s “Oh Honey,” Kansas City Express’ “This is the Place,” and Japanese jazz trombonist Hiroshi Suzuki’s “Romance” (the last song, off the artist’s 1975 album Cat, is so gooood).

I mostly like printed shirts this time of year because they offer an interesting alternative to the pique cotton polo. A bolder shirt pushes an outfit away from business casual territory; it adds visual interest. And while I still like crisp white linens and light-blue oxford-cloth button-downs, it helps to have some bolder prints for the weekend. From retro to contemporary, here are the best prints I’ve seen this season:

Keep reading