In August of 1942, not long after Germany took over Paris, Samuel Beckett and his companion (later wife) Suzanne Deschevaux fled their apartment in the French capital. The pair had been working in a Resistance cell known as Gloria, where they translated Axis documents and relayed information about troop movements for Allied powers. The info was coded into microfilm, hidden in candy boxes and slipped into toothpaste tubes, and then passed along through a chain of Gloria members, with each person reporting to the next in line, until the message reached Allied headquarters in London.

That year, however, Gloria was betrayed by Robert Alesch, a Catholic priest and double agent who sold out hundreds of Resistance agents for his own financial gain. As a result, the Gestapo went around the Paris rounding up Gloria members and other anti-Nazi agents. One of the people arrested was Alfred Péron, a Jewish writer and Beckett’s closest French friend. He was interrogated and eventually deported to one of the most notorious concentration camps, Mauthausen on the Danube River. All categories of prisoners here, from Jews to gays to political opponents, were starved, beaten, used for medical experiments, and subjected to slave labor in the local stone quarries. Péron survived until the end of the war, but tragically died two days after the camp’s liberation in 1945.

In researching for Beckett’s biography, James Knowlson interviewed the extraordinary Germaine Tillion, one of the first Gloria members to be betrayed by Alesch. She was involved with one of the earliest underground organizations of the French Resistance, the Musée de l’Homme, and many of her friends had been executed by Nazis. Knowlson writes of the interview at The Independent:

Germaine was convinced that the traitor was the now notorious Albert Gaveau. She was, she said to me, so sure of this that she had hoped, if ever she had the chance, to “neutralise” him. She used the French word: “neutraliser.” What exactly did she mean by “neutraliser,” I asked her. “I had a revolver at the time,” she calmly explained. Then she raised her hand to her forehead in an unmistakable gesture: “Phfut!” she said. (The word “neutraliser” is commonly used in this sense by French Special Forces.) Since then, I can never hear this verb, either in English or in French, without thinking of that tiny, bespectacled, 90-year-old lady, sitting in her armchair in the sitting-room of her country house in Brittany, calmly announcing her intention to blow out someone’s brains and regretting that she had not been able to do so.

Beckett and Deschevaux were much luckier. After Gloria was compromised, they managed to escape from the Gestapo by the skin of their teeth. The couple headed south, making their way by ducking into sheds, sleeping in parks, and hiding in trees and haystacks to evade Nazi patrols. As Beckett told his biographer Knowlson:

I can remember waiting in a barn (there were ten of us) until it got dark, then being led by a passer over streams; we could see a German sentinel in the moonlight. Then I remember passing a French post on the other side of the line. The Germans were on the road; so we went across fields. Some of the girls were taken over in the boot of a car.

After about six weeks on the lam, the couple arrived at Roussillon, a small village located in southeastern France. Roussillon at the time was located in the Unoccupied Zone, remote and inaccessible to heavy military vehicles, and friendly to refugees. Beckett and Deschevaux decided to wait out the war here, renting out a home on the edge of town. But Beckett, who was prone to anxiety, soon suffered a mental breakdown.

“His biographers disagree on its severity, but there is no doubt that the trauma of his friends’ arrests, his escape from Paris, and his separation from the artistic and intellectual life in the capital – compounded by his guilt at being away from his family, especially his mother, during a time of war – all took a toll on him,” Jon Michaud writes of those years in The New Yorker. “Beckett passed his time playing chess, going for long walks, and working in a neighboring farmer’s fields in return for food. […] He also labored on a novel, Watt, which he’d begun the previous year, in Paris, and which, he said, provided him ‘a means of staying sane.’ Deirdre Bair, in her biography of Beckett, describes work on the novel as his ‘daily therapy.’”

Beckett also participated in low-level resistance. He retrieved supplies dropped from planes, and stored them on his rented property until he could pass them along to Allied troops. He planted bombs in empty houses in case the Nazis managed to break into Roussillon. And towards the end of the war, he and his friends planned to ambush retreating Germans. But like Godot in Beckett’s most famous play, the Germans never arrived. By the war’s end, Beckett returned to Paris, then London and eventually Dublin, where he saw his mother for the first time in years. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre for his work in Gloria, but he dismissed his role as “Boy Scout stuff.”

During the years he was in Roussillon, Beckett lived near one of the village’s many red-rock plateaus. The bucolic town is perched on top of a mountain, surrounded by pine trees and oaks, and the sandy clay soil here is intermingled with high levels of harder crystalline iron ore. Those deposits give the steep cliffs a brilliant explosion of color – burnt sienna and ochre yellow, which are set off by the lush green forests and pearly blue skies in the background. The ochre-bearing limestone hills are the result of the sea retreating from Roussillon, which once submerged the area millions of years ago.

The French touristry industry likes to give a more fanciful explanation for the region’s ruddy color. During the Middle Ages, a young damsel named Sermonde was married to the Lord of Roussillon, who was obsessed with hunting and, as a result, often away from home. When the Lord found out that his wife was having an affair with a handsome young troubadour named Guillaume, he killed Guillaume and tricked Sermonde into eating his roasted flesh for dinner. Lady Sermonde screamed, her screams filling the room, the chateau, and soon the village. Before anyone could stop her, she lept to her death from the chateau’s highest tower, forever staining the hills with her blood. That, apparently, is how the French tourism industry promotes the region’s spectacular gorges, forests, and tributaries as one of the country’s most popular summer destinations (to their credit, it works, as thousands of people come here every year).

Those red and yellow rock formations have also been a natural source of wealth for the region. People have been mining ochre for thousands of years, using the natural pigment as a coloring agent for everything from cave paintings to pottery to tattoos. Around the time of the French Revolution, however, a French scientist named Jean-Étienne Astie discovered a way to make the pigment on a large scale by mining ochre from Roussillon’s cliffs. To shorten a story that only chemists will find interesting, ochre is a family of clay earth pigments, mostly red-yellow in color, that’s made up of ferric oxyhydroxide, a chemical compound of iron, oxygen, and hydrogen that’s also known as limonite. To change the color, a chemist can heat up these pigments until they dehydrate, turning some of the limonite into hematite. That’s how natural sienna becomes burnt sienna, and umber transforms into burnt umber.

Astier’s method involved extracting large amounts of red-yellow clay from Roussillon’s open pits and mines. The clay was then washed and decanted into large basins, which separated the ochre from sand. The ochre was then dried, cut into bricks, crushed, sifted, and classified by color and quality. The best qualities were reserved for artists and house paints, while the rest was used in linoleum, paper, cardboard, and textile industries. During the 19th century, Roussillon exported the color around the world in as many as seventeen shades, each one manufactured from the local rock.

Roussillon’s economy was largely dependent on its ochre production until the end of World War II. Overmining threatened to degrade protected sites; the economic crisis of 1929 closed down foreign markets one by one. By 1958, mass production of ochre pigment finally stopped when someone found a way to synthetically produce the color for much cheaper. Today, however, the region still relies on ochre for its exports, but the clay never leaves the village. Tourists from around the world visit Roussillon so they can walk along the footpath of the Le Sentier des Ocres and appreciate the beauty of the cliffs.

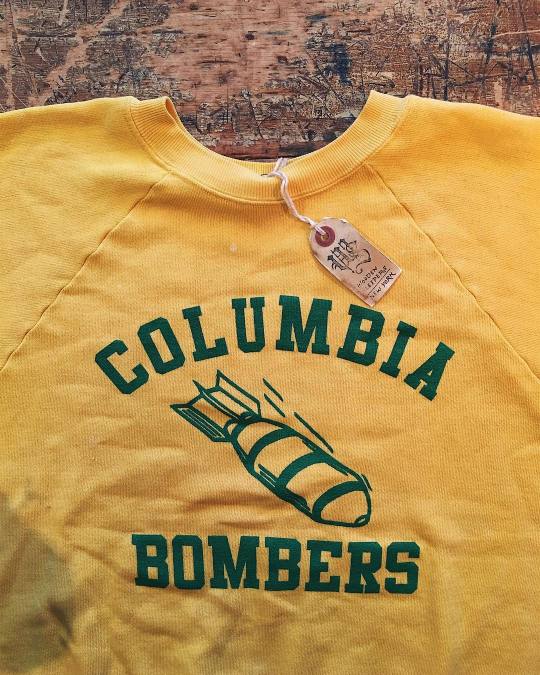

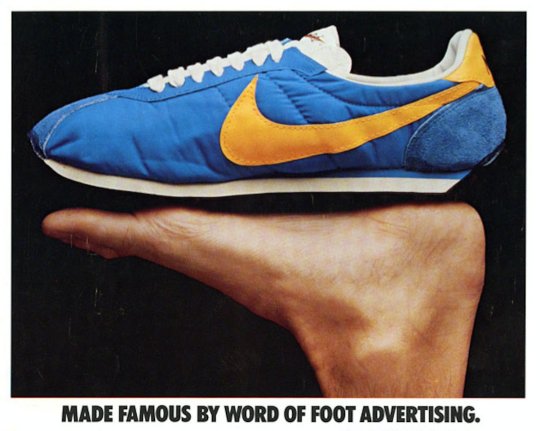

I think ochre may be one of menswear’s most underrated colors. The golden hue is cheery enough for spring and summer, but it’s also appropriately earthy for fall. It somehow manages to be both modern and slightly retro. In a post about rust colored ties, a close cousin of ochre, David Isle once wrote: “Rust is distinctive and unobtrusive at the same time. Basically any time you wear a light blue shirt, you can also wear a rust tie. It’s particularly good with brown sport coats, where it’s like a streak of red clay in a muddy riverbank, or with green sport coats, where rust is red enough to be complementary to the green, but not so red as to look like a Christmas costume.”

During the early years of Frank Mujtjen’s tenure as the head of J. Crew’s menswear design, the company often relied on burnt ochre to highlight their gray flannel suits and navy puffer coats. And it’s no wonder. In a recent Vanity Fair video, movie poster artist James Verdesoto explains the logic behind iconic posters such as Pulp Fiction, Ocean’s Eleven, and Training Day. “A yellow background provides an independent voice,” he explains. “Indie films also have smaller marketing budgets and yellow is a cheap way to catch the eye.” Canary yellow can be a bit brash when used in clothing, but burnt ochre is a perfect highlight. For those who are just starting to spin around the rest of the color wheel, ochre is a safe and reliable starting place.

The easiest way to incorporate ochre into an outfit is through knitwear. Tuck an ochre Shetland sweater from O’Connell’s, Neighbour, or Harley underneath an emerald green Barbour jacket or a dark brown suede bomber. The Shetland Woolen Company and Far Afield have textured options if you want something more distinctive. Sunspel also offers thin merino crewnecks, Caruso has silk-cashmere turtlenecks, Paa sells hooded sweats, and Lemaire makes boxy saddle-shouldered knits. Or you could opt for any of the simple jerseys from Camoshita, Our Legacy, Pilgrim Surf + Supply, Oliver Spencer, and The Garbstore’s English Difference line.

Far and away, my favorite this season is the terry cloth Camoshita polo you see above, which was styled by Trunk Clothiers. It has a larger collar and wider placket, a loose cut, and stylish old Hollywood vibes. Trunk Clothiers already sold out of their stock, but you can still find the polo at No Man Walks Alone, Mr. Porter, and Lane Crawford. Alternatively, A Kind of Guise’s linen-cotton button-up and Nine Lives’ water-resistant work shirt can be worn with chinos or jeans in much the same way. There’s also this absurdly priced silk shirt from Maison Margiela if you have money to burn.

For something bolder, you can try Sid Mashburn’s travel sport coat, Oliver Spencer’s cowboy jacket, or the two nylon taffeta jackets this season from Engineered Garments. If you’re just looking for a small accessory to serve as an accent, Sozzi’s rust-colored knit tie would do wonderfully with summer sport coats, Pampa’s turmeric wool scarves can be worn with slightly oversized topcoats, and Carhartt WIP’s low-fitting beanie would be good for skate- and workwear-inspired ensembles. Personally, I’ll be wearing that Camoshita terry cloth polo this season with self-belted Lemaire pants and Margiela’s slip-on shoes, imagining how Beckett spent his days in Roussillon staring at ochre-bearing limestone cliffs while thinking about how much he hates Nazis.