In an interview with The Telegraph, Patrick Grant of Norton & Sons once described fashion as being an “ever-moving feast.” I find that the quick-paced nature of fashion — where things are constantly being created and destroyed — makes the field endlessly interesting. There’s always something new, something different, something to talk about. For the past few years, I’ve been doing annual roundups on new brands I find to be interesting. To be sure, not all of them are new — many have been around for years — but they’re new to me. This year, there are so many brands on the list, I’m splitting the post into two parts. Here’s part one, with part two coming in the next installment.

GHIAIA CASHMERE

When Davide Baroncini left his job at Brunello Cucinelli, he didn’t want to work for another luxury label. It would be strange, he said, to suddenly go from telling people that Cucinelli makes the best clothes to championing Tom Ford. So he started his own brand, Ghiaia Cashmere, which is named after the smooth pebbles found on the shoreline of his native Sicily. Baroncini says the name represents him returning to his roots, the memory of feeling the ground underneath his feet. It also suits a company specializing in thin, luxurious knitwear designed for Mediterranean climates, such as Sicily and Baroncini’s newly adopted home, Pasadena. Plus, it sounds nice, so long as you can pronounce it (say it slowly, it’s jhe-EYE-ah).

Baroncini opened his first brick-and-mortar store last year during a global pandemic. The store is located at Pasadena’s Burlington Arcade, which is modeled and named after the London original (the store occupies the same space that once housed the neo-trad menswear shop The Bloke). When you step inside the store, you feel like you’re under a capsized boat. The high ceilings have been painted black to make them feel lower, making the space feel as cozy and intimate as the company’s plush knitwear. Spread around the store are bare wood furnishings, threadbare rugs, framed nautical photos, tasteful Scandinavian lighting (sourced from Muuto and Louis Poulsen), and a Denti road bike to remind you that the company’s owner is a sporty Italian man.

The prices here are stratospherically expensive. Fine gauge cashmere crewnecks start at $645, cashmere knitted polos are $785, and cashmere joggers (sweatpants, essentially) are $895. Cotton shawl collar cardigans finished with wrapped leather buttons top the price chart at nearly $1,000. I assume the prices are high partly because of how the clothes are manufactured. These fully-fashioned knits are made in Italy using cashmere yarns sourced from Cariaggi, the same company that supplies Baroncini’s former employer, Cucinelli. I also assume distribution plays a role. The company’s first stockist was Neiman Marcus, and luxury retail partners need margins to eat.

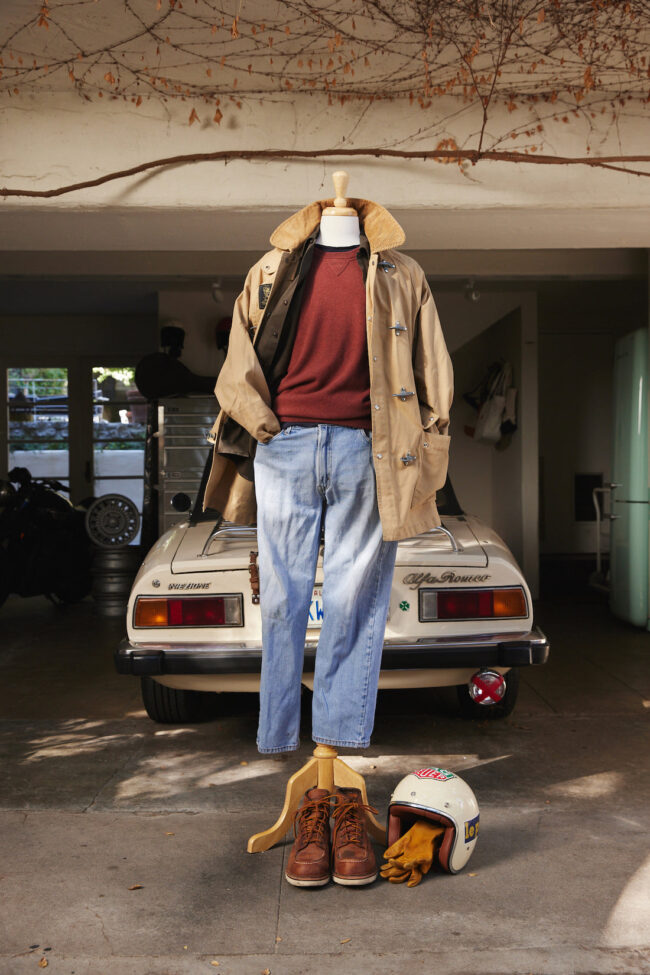

I’ll probably never be able to afford something here, but I love the company for its styling. A quick scroll through their website will feel oddly familiar and novel at the same time, not unlike how Ralph Lauren makes the commonplace feel aspirational. The product images, which are shot in Baroncini’s garage, are beautifully styled with brightly colored Fay fireman coats, chestnut leather Red Wings, light-washed jeans, floppy bucket hats, and five-inch shorts. There’s something familiar in how they incorporate Italian and American icons of the hashtag-menswear era, but mixed with a sporty California flavor that makes them feel more relevant and casual for today. I also love their photographic features on customers, such as this one on real estate investor R. Stephan Hogan. The silver fox is shown wearing a Russell plaid tweed with his stone-grey Ghiaia crewneck (I had Steed make me a similar sport coat many years ago).

“It’s clear to everyone that we make sweaters,” Baroncini recently joked in a Blamo interview. “But what’s funny is that, when we use other products, we always have a bunch of guys like, ‘what’s the pant?’ or ‘what’s the shoe?’ My wife laughs at me because I’m like, ‘how is that important to you? I’m selling the sweater!'” On the upside, Baroncini says he’ll soon be introducing new products into his range, including pants, outerwear, and footwear. I’m excited to see what they do next.

BLACKSTOCK & WEBER

Every once in a while, someone will ask me if I think classic men’s tailoring will be popular again. In the future, I think I will refer them to Chris Echevarria, founder of the NYC-based footwear label Blackstock & Weber. Echevarria understands something important about clothing: you can’t convince people to dramatically change how they dress. Instead, you have to remix things in a way that makes sense for their cultural context and identity.

Before starting Blackstock & Weber in 2016, Echevarria studied menswear design at the prestigious Fashion Institute of Technology and then worked for J. Crew’s Liquor Store and M5 Showroom. He was there to witness how New York City’s cubicle farmers picked up heavy-duty (and frankly, largely uncomfortable) Red Wing work boots as white-collar fashion items. And how Stone Island’s patch turned from being an emblem of British football hooliganism to American street culture. Both of these stories are about how classic items were remixed to make sense to a new demographic.

When Echevarria started his footwear label, he applied these lessons to his brand. Blackstock & Weber has been at the forefront of the “post sneaker movement,” where young guys, exhausted from the hedonistic treadmill of chasing endless limited-edition drops for less-than-stellar shoes, have been turning to “hard bottom” styles such as loafers. However, they don’t want the geriatric loafers that you can find at Alden or Crockett & Jones. Instead, they want something that speaks to them.

Echevarria has been there to greet these post-sneaker consumers with designs that sit somewhere between classic men’s style and streetwear. His loafers tick all the right checkboxes for quality: Goodyear welted, made in England, and constructed from full-grain leathers. However, the styles are anything but conservative. The wide welts and double-leather soles give these shoes a chunky silhouette. Echevarria also uses unique leathers and playful color combinations, often reminiscent in spirit, if not the exact aesthetic, of cool sneakers.

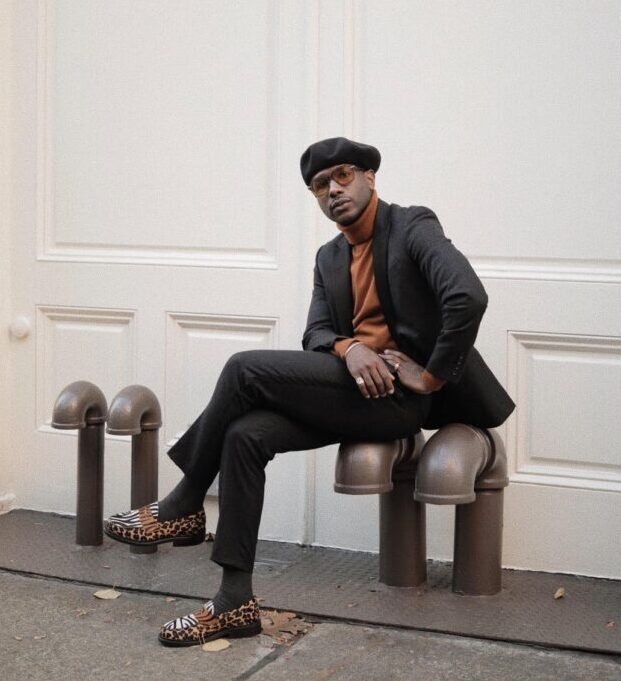

Dyed-in-the-wool trads will raise an eyebrow at many of these styles. Many will look like Frankenshoes if you’re not used to a streetwear aesthetic, as summer slip-ons are often finished with clunky, boot-like soles. But that’s the point: people buying these don’t want to look like they argue about collar rolls. When you scroll through the tagged section of Blackstock & Weber’s Instagram, you can see how customers skillfully work these styles into youthful outfits. I love the way Joekenneth Museau wears safari loafers with a trim charcoal flannel suit, and how Nolan White teams spotted loafers with a 1970s sleaze, boho-chic aesthetic. Realistically, I would probably wear the more sedate black horsebits or brown pennies in the way you see them on Chris Jackson or Greg Lellouche’s Instagrams. If tailoring returns, I think it will return in a different form, and it will require someone like Echevarria to make the style relevant to a new demographic.

FRIZMWORKS

Over the last ten years, fashion prices have significantly outpaced inflation, with men’s clothing prices leading the way. So I wanted to include more affordable brands in this year’s list as a way to make these guides useful for people across a range of budgets. Unfortunately, many affordable brands only sell generic clothes — oxford button-downs and plaid flannels, slim-straight chinos and raw denim jeans, and the same but slightly different work boot.

There are some notable exceptions in South Korea. Younger, lesser-known companies such as Uniform Bridge, Outstanding Co., and Big Union are riffing off Americana, workwear, and heritage-style clothing. Mano Dridi, the warm and friendly director at All Blues Company, a Leeds-based menswear boutique that has introduced many of these labels to the Western market, says it’s about how the South Korean economy is structured. “South Korea is a rich country, and people have a lot of money to spend,” he explains. “For decades now, people were already buying expensive fashion from all over the world. But now we’re seeing young people start their own companies, and it’s easy because of how the factories are set up. In China or the United States, a factory might have a minimum purchase order in the thousands. In South Korea, the minimum is nothing. The factories are willing to work with anyone with ideas. These new clothing brand owners are very young — in their 20s and 30s — and they’re all working in these little offices. They are very lean companies with little overhead, so all the money is going into clothing quality.”

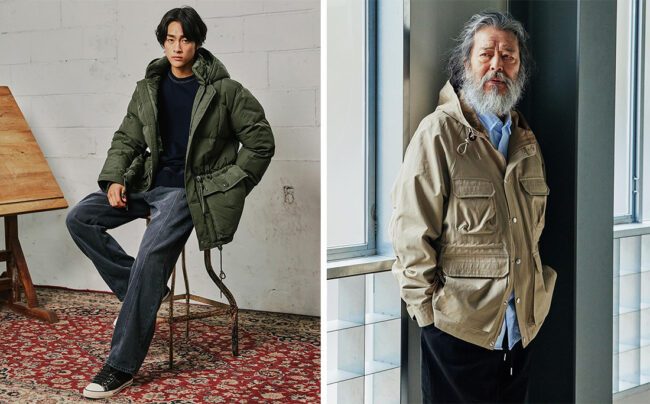

These companies often have extensive catalogs full of interesting designs, many of them sold at relatively affordable prices. Coldwarm has lightly padded, mountain parkas made from a water-resistant shell and synthetic filling. The parkas cost $360, which is not much more than what you’d pay at J. Crew. Outstanding Co. has hunting jackets for $138, patchwork climbing pants for $125, and retro-styled mohair cardigans for $109. “If you were to see these items from a Japanese or American brand, they would easily cost three or four times as much,” says Dridi.

Jong Hyuk founded one of these companies, FrizmWORKS, in 2010 when he was a student at Konkuk University. “It started as a fun project and then turned into a career. This project is also why I ended up graduating late,” he jokes. “Although I studied contemporary art, not fashion, my studies taught me how to express myself visually. I then learned how to design by working with mills and factories.”

FrizmWORKS mostly designs around militaria and what Hyuk calls “American casual.” His company’s mountain parka is modeled after an American classic, Eddie Bauer’s Kara Koram, which was originally made for a team of American mountaineers and has since become a grail for vintage collectors. It’s not inexpensive at $550, but it’s cheaper than the RRL version and features an 80/20 mix of duck down to feather filling. They also have deck jackets ($300), USN anoraks ($116), padded fleece jackets ($116), fishtail parkas ($135), and hunting coats ($135). “I’m proudest of our outerwear because they’re difficult to make,” Hyuk says of the line. “My favorite is our Utility Mountain Parka, which took a year from design to production.”

BELLIEF

Scour the internet for affordable South Korean brands and you’ll find that many, if not most, specialize in workwear, Americana, and streetwear. As the fervor for heritage-style clothing is dying down, many of these workwear brands are also switching to making 90s style baggy jeans and silk-screened sweatshirts.

Readers looking for dressier clothes will want to turn to Bellief. Founder Jung-Ki Park has a strong love for Italian “sartorial” clothing — soft-shouldered suits and sport coats, one-piece collar shirts, and trimly tailored trousers. His company has a similar “refined but relaxed” feel, but more in the vein of Saman Amel than Boglioli. They have side-tabbed, reverse-pleated trousers made from basic flannels and hard-to-find coverts. Fine-gauge knits come in modern, earthy colors such as taupe, clay, and two shades of cream. I imagine many readers will be interested in the wool Balmacaan coats (just $320 with the checkout code BLUES10). “They’re incredible coats for the price,” says Dridi. “The difference between something like this and Drake’s Balmacaan is that Drake’s version is built for a Western body type. Many South Korean brands will make clothes with slightly shorter sleeves and narrower shoulders, much like you see from Japanese brands. I’m of average height and can wear one of these Bal coats with room for layering, but someone taller may find the sleeves too short.”

Sizing and sourcing are the two largest hurdles when purchasing South Korean labels. I recommend going through a shop such as All Blues Company (they deserve the business anyway, as they’ve introduced many of these brands to the Western market). Dridi and his team can answer questions about sizing, and their Instagram is full of good styling ideas. Although their official policy is that they don’t take returns from overseas orders, they’re also a small shop that’s amenable to working with customers if things don’t work out (be reasonable). Buying something from one of these labels will be more challenging than clicking checkout at a domestic boutique, but the hassle may be worth it when Mr. Porter sells $6,610 nubuck chore coats and $12,300 sequined sweatpants.

CASATLANTIC

The companies I include in these lists aren’t always things I want to buy and wear myself. Sometimes I include a company that I think is interesting; other times, they make beautiful, even if outré, things. Often, the prices are too high or the products physically inaccessible, but I enjoy following the brand anyway. These lists are about the brands I’m watching, not always what I’m buying.

Casatlantic is the opposite. The newly founded company specializes in wider cut trousers made from sturdy cottons and heavy linens. It’s a one-man show run by the strikingly handsome Nathaniel Asseraf, one of the two brothers running Broadway & Sons, a family-owned vintage shop in Gothenburg, Sweden. Nathaniel’s father, David, started the vintage shop in 1982 and has lived a romantic life. Shortly after the May 68 protests, David, then a 15-year-old Moroccan teen living in Paris, hopped on a plane and flew to Sweden to be with his then-girlfriend. After a few short years of living there, he met Solomon Schwartzman, an American military surplus dealer who confidently told him: “David, sell vintage clothing, and you will never lose money!”

That advice sent David around the world. For decades, he shuttled between Paris and Los Angeles, where he bought bales of vintage t-shirts, original Levi’s 501 jeans, collegiate sweatshirts, and Army-issued sneakers to resell in Sweden. He once even bought 90,000 pairs of jeans — five containers full of Levi’s, Lee, and Wrangler five-pockets — from a Chicagoan dealer looking to get out of the business. “I think my obsession followed the 1970s era when this flower power thing bloomed after the [Vietnam] War,” David told The Rake. “Those who know me know I always discuss the price, so I got [those jeans] for less than fifty cents apiece, rather than a dollar.”

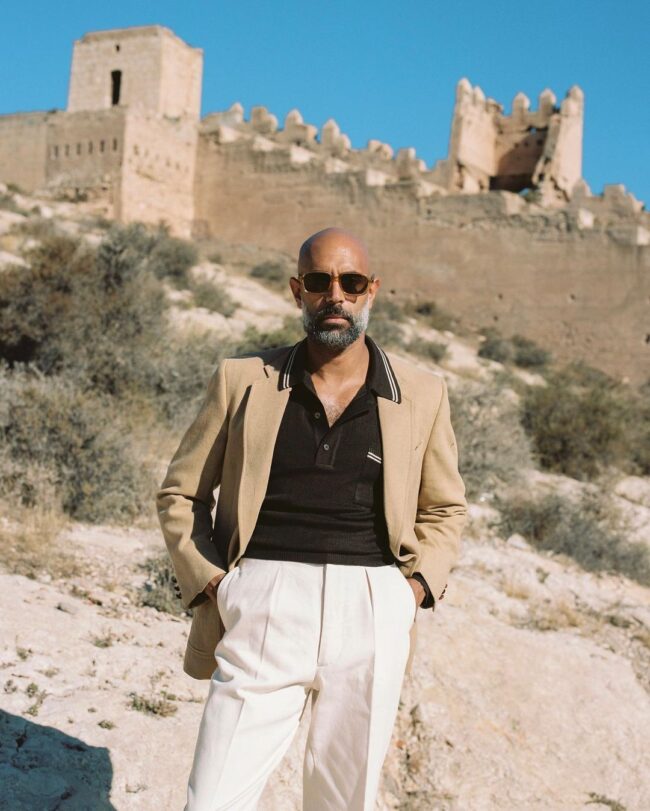

What started a vintage obsession has turned into a generational business. David’s two sons, Nathaniel and Noam, have given Broadway & Sons a boost by remaking the store’s presentation and creating an online presence (their Instagram is very inspirational). Nathaniel has also followed in his family’s footsteps by selling pants. His company, Casatlantic, is inspired by his grandfather, who has always worn loose-fitting camo trousers with Converse sneakers and oversized shirts. “As my curiosity to learn more about [my family’s history grew, my grandfather] showed me more and more photos of how he and his friends dressed when they were young,” he once said in an interview. “[They wore] military clothing with alterations by local tailors […]. Perfectly fitted trousers with Army shirts. I was deeply […] inspired by that style and wanted to bring that [back to] life, as it was hard finding something similar on the market. And from there, I built the foundation for Casatlantic.”

These are not your slim-straight J. Crew chinos. They’re modeled after pants that French and British officers wore in the 1950s and ’60s while stationed in North Africa. They are directional, with leg openings ranging from 8″ to 9.5″, but are classic enough to harmonize with workwear, Americana, and heritage-style clothing. As a nod to his roots, Nathaniel also has these made in Casablanca, Morocco, where his father and grandfather were born. I’ve been getting into looser-fitting trousers in the last few years as a way to make casual outfits more interesting. I love the idea of wearing the Mogador or Safi with a roomy topcoat, rounded bomber, or vintage Lee 101J trucker (which has become a staple in my wardrobe). Mercifully, the pants are also reasonably affordable at $170, which makes experimentation a little easier to stomach. If you comb through Nathaniel’s Instagram (again, endlessly inspirational), you will often see him wearing Casatlantic trousers with a range of different outfits. One can only hope to look as good in these pants, although a small part of me fears I will look like a young Jeff Bezos.

NORBIT

For a small country, life in Japan can sometimes feel even smaller, as nearly 92 percent of the population lives in one of the crowded cities. If you include the greater Tokyo metropolitan area, which is spread over Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba, about 36 million people call greater Tokyo their home — roughly a third of the country’s total population. Yet, outdoor hiking is one of Japan’s great pastimes. People of all ages love to go hiking in the countryside, as well as dress up for it — putting on the right jacket, choosing the proper boots, and pulling out the ideal bag. This is especially true of older people, who have a lot of money and even more time.

My friend Kyle, who recently moved to Japan with his family, tells me that these are specific kinds of hikes. “What it really means is taking the train a few stops outside of your city, then going for a walk on an existing path through nature,” he explains. “It’s very pleasant, but nobody needs all that gear; they just love wearing it. And when you take the train in Japan on a nice day, outside of rush hour and heading into the countryside, you’ll literally be surrounded by people wearing the sort of outdoor gear you see in Japanese magazines. They’re all going hiking.”

The technical apparel boom in Japan is far more inspiring than what you can find in the United States. Brands such as Nanamica, And Wander, F/CE, South2 West8, and Snow Peak specialize in melding technical performance with style (American gear, on the other hand, is sometimes technically advanced, but often ugly, clammy black shells). One of the more interesting brands in this space is Norbit. Although it was technically founded in 1999, the brand laid dormant for many years, as founder Hiroshi Nozawa worked as a designer for Fjallraven, New Balance, and the Japan-only Columbia Black Label. He even helped Snow Peak launch their first-ever apparel collections. Then a few years ago, he dusted off the Norbit name to design his own line, and some notable boutiques have since picked it up (Mr. Porter, The Bureau Belfast, Mohawk General Store, HAVN, and This Thing of Ours among them).

Norbit is a busy intersection of past and present, traditional and technical, reality and fantasy. Nozawa grew up in the countryside of Hyōgo, a prefecture famous for the beef that comes out of its capital city, Kōbe. He describes his younger self as a “sports-minded boy” who used the neighboring mountains as his playground, where he preferred to explore dark caves rather than study. When he started to design outdoor clothing as a man, he found himself often reaching back to those childhood memories. “I imagine a scene in my mind, and try to have a vision of what kind of clothes are suitable for that situation,” he explains. “At this moment, the designs are just vague images. The next step is sketching to express the images in a tangible form.” This is how he transforms sensory portraits into off-beat, workwear fantasy garments.

Nozawa’s designs are like Snow Peak meets Ralph Lauren’s Polo Country, with a slow drip of Visvim’s Japanese Americana. They look like something a character in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away would wear in a winter-frosted valley, maybe with chimes singing in the background and spirits drifting over flowers. Some things will look vaguely familiar, such as the toggles reminiscent of duffle coats, but then made unrecognizable through the use of hunting patches or storm flaps. Rugged workwear styles are often finished with strings, which you’re meant to tie into a delicate bow. “Military, work, and hunting clothing, they tend to look very hard,” Nozawa says. “I try to add curved lines and stitching to make my clothes more soft and mellow. This is the big point of Norbit’s design work. I make an effort to communicate well-balanced beauty — rocky stretches, forests, lakes, and sky being in harmony with one another — through my design work.”

As a line, Norbit is not always the easiest thing to wear. The clothes are often unmoored by traditional designs, as Nozawa introduces unconventional closure systems such as asymmetrical, zippered down vests. This two-string waterproof anorak will leave you looking like an expensive present, while the oversized boa-fleece coat requires the right pants to finish the silhouette (luckily, Norbit also sells them). On the other hand, some of the more familiar items, such as the printed hunting shirts and Mountain Hike jackets, can be worn in the same ways you wear many Japanese workwear labels. I love how Norbit forces me to abandon the rules and enter this fantasy world of outdoor gear. “Because of the internet, young people know more about fashion than I did when I was their age,” says the designer. “I cannot give them any comments, as I should learn from them. But if I can give them some words, I would like to say, please treasure your feelings and not depend on information or knowledge.”