At the turn of the 20th century, Kentucky humorist Irvin S. Cobb published a book of essays under the title Roughing It De Luxe. It was about his travels out West using railway passenger cars, which at the time had become the new middle-class luxury. Cobb was acutely aware of how his smooth passage contrasted against Mark Twain’s stagecoach journey fifty years prior, so he peppered his essays with wry musings about the upscale services and fine dining available to him. He wrote:

Starting out from Chicago on the Santa Fé, we had a full trainload. We came from everywhere: from peaceful New England towns full of elm trees and oldline Republicans; from the Middle States; and from the land of chewing tobacco, prominent Adam’s apples, and hot biscuits — down where the r is silent, as in No’th Ca’lina. And all of us — Northerners, Southerners, Easterners alike — were actuated by a common purpose — we were going West to see the country and rough it — rough it on overland trains better equipped and more luxurious than any to be found in the East; rough it at ten-dollar-a-day hotels; rough it by touring car over the most magnificent automobile roads to be found on this continent. […] Two thousand miles from saltwater, the oysters that are served on his dining cars do not seem to be suffering from car-sickness. And you can get a beefsteak measuring eighteen inches from tip to tip. […] If there was only a cabaret show going up and down the middle of the car during meals, even the New York passengers would be satisfied with the service, I think.

Conspicuous among Cobb’s fellow travelers was a hodgepodge of well-to-do people. There was the Chicago surgeon who was so distinguished, he had a rare disease named after him; a woman who enjoyed stepping out onto the train platform at every stop, so she could expand her accordion-plaited camera and snap a few photos of the scenery and people; and a corn-doctor from Indiana who was anxious about everything, from breakfast preparation to the proper clothes he should wear when finally faced with the splendor of the Grand Canyon. When the corn-doctor asked our essayist for style direction, Cobb politely replied that he could not be of any help. “I had decided to drop in just as I was, and then to be governed by circumstances as they might arise; but he was not organized that way,” Cobb remembers. “On the morning of the last day, as we rolled up through the pine barrens of Northern Arizona toward our destination, those of us who had risen early became aware of a terrific struggle going on behind the shrouding draperies of that upper berth of his. Convulsive spasms agitated the green curtains. Muffled swear words uttered in a low but fervent tone filtered down to us. Every few seconds, a leg or an arm or a head, or the butt-end of a suitcase, or the bulge of a valise, would show through the curtains for a moment, only to be abruptly snatched back.”

Trips out west were not always so mild and pleasant. Before the advent of the modern passenger train, brusque and burly men working at lunch station counters along the Trans-Mississippi West railway served rancid bacon, canned beans, and eggs known as “stinkers” to racing passengers. Dirty dining tables were covered in chipped crockery broken by “hash slingers” impatiently waiting on customers. Diners were given the choice of washing their meal down with either bitter tea or cold coffee, and then had to wipe their mouth with their back of their hand, as there were no clean napkins available. “Passengers hoping to avoid the chronic dyspepsia produced by station cafés brought box lunches or purchased sandwiches from the ‘butcher boy’ on the train,” Keith Bryant Jr. wrote in his book History of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway. “Forty or fifty people eating box lunches in a passenger coach crossing Kansas on a warm July day created an unbelievable odor that attracted swarms of black flies.”

Mercifully, change came in 1874 when an immigrant named Frederick Henry Harvey leased a lunch counter along the Santa Fé line. Born into a poverty-stricken family in London in 1835, Harvey fled to America as a teen searching for a brighter future. He first settled in the nation’s cultural capital, New York City, where he worked for a time as pot scrubber and busboy at Smith and McNell’s restaurant, earning $2 a week. Finding his work taxing and unrewarding, he moved to New Orleans, where he contracted yellow fever. (The same epidemic killed the family of George Francis Train, later an important mercantilist and railroad financier, whose rip-roaring, adventure-packed life inspired Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in Eighty Days.) Upon recovering from yellow fever, Harvey moved to St. Louis, where he contracted typhoid during the Civil War. He then ultimately landed in Chicago, where he worked for a railroad company.

Harvey’s experience going through small towns dotted along the railway made him intimately familiar with the poor conditions travelers had to endure. He was convinced that railroad eating facilities could provide quality food, good service, and pleasant surroundings while still turning a profit. So in 1876, he met with Charles F. Morse, a superintendent of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fé railway, to explain his idea. Dressed in a conservative business suit consisting of a “long coat, tight pants, and string bow tie,” the tall and wiry Englishman cut a distinguished figure and impressed the Santa Fé superintendent. Shortly after the meeting, the company president agreed to give Harvey a try — he would lease the Topeka lunch counter to him.

Main lobby room, El Ortiz Hotel, Lamy #NewMexico, 1912

Photographer: Jesse Nusbaum (POG 061674) pic.twitter.com/adFHs4anRP— POG Photo Archives (@pogphoto) October 4, 2018

Sealed with nothing but a handshake, this deal radically transformed passenger car services, our ideas about luxury and leisure, and most importantly, American aesthetics. Harvey’s clean, moderately priced dining rooms became a booming business, and he later expanded into sleeping accommodations. As Santa Fé laborers built westward, Harvey closely trailed behind, building picturesque hotels and fine dining rooms near train depots. To keep food quality high, chefs used local pheasants, quails, and fresh-farm eggs for their exquisite European cuisines. Refrigerated shellfish, sea bass, and sea celery were shipped in from the coasts. Clean water for coffee was brought in using tank cars, rather than taken from nearby alkaline streams. One day, while visiting one of his establishments, Harvey heard a clamor in the dining room. He rushed out from the kitchen and found a frustrated steward complaining about a cranky diner who could not be pleased. “Of course, he is a crank,” Harvey agreed, “but we must please him. It is our business to please cranks, for anyone can please a gentleman.”

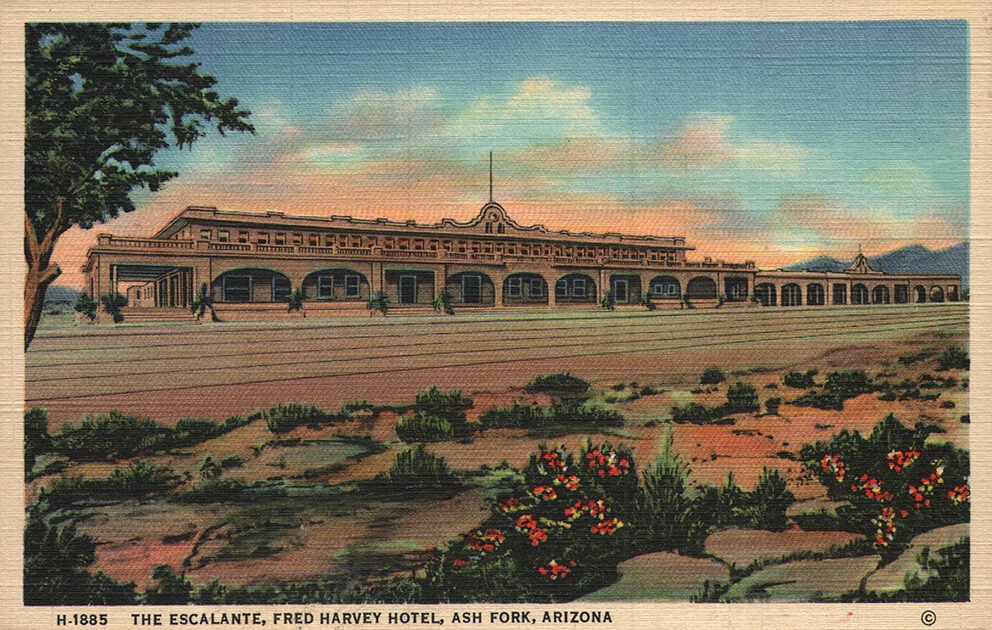

Before there was ever a Hyatt or Hilton, activity-seeking Americans traveling westward made Harvey Houses their central place of stay. The Fred Harvey Company named these establishments after the period of Spanish rule in the American southwest — the El Ortiz in Lamy, La Fonda in Santa Fe, El Vaquero in Dodge City, and Castañeda in Las Vegas, among others. Landmark locations were designed by Mary E.J. Colter, an expert on Southwestern art and one of the only female architects of her day. Drawing on the history of the Southwest, Colter incorporated Spanish Colonial Revival and Mission Revival architecture, Native American motifs, and rustic elements into her structures. Many of her buildings were distinguished by their adobe faces, decorative tile work, massive wooden buttresses, and warm, earth tone colors such as clay red, burnt umber, and sunset orange. Shortly after visiting one of Colter’s picturesque locations, Western novelist Owen Wister wrote: “The temptation was to give up all plans and stay a week for the pleasure of living and resting in such a place.”

Colter’s first Harvey project involved building the Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This palatial hacienda housed a restaurant, barbershop, men’s and women’s parlors, club room, reading room, and about a hundred guest rooms (eventually expanding to a hundred and twenty). Roofed in red tile and covered in rough stucco, the Alvarado Hotel was something of a noble temple for a glorious age of interior travel. It was distinguished by its Spanish mission-style architecture, black oak-paneled interiors, carved beams, and lush gardens full of award-winning roses. Colter also designed one of the smaller, hidden gems in the Harvey network — a two-story adobe structure in Lamy, New Mexico named El Ortiz, which served as a transfer point in the Santa Fé railway system. For a time, it was known as Honeymoon Hotel because of how the intimate space and remote location made it popular with newlyweds. Inside, visitors could find richly toned woodwork, brass accents, Spanish-style furniture, Navajo weavings, and one of Colter’s signature fireplaces decorated with a parabolic arched opening. Sadly, both locations eventually shut down and were later demolished, but you can find breathtaking scans of their postcards on Etsy and eBay.

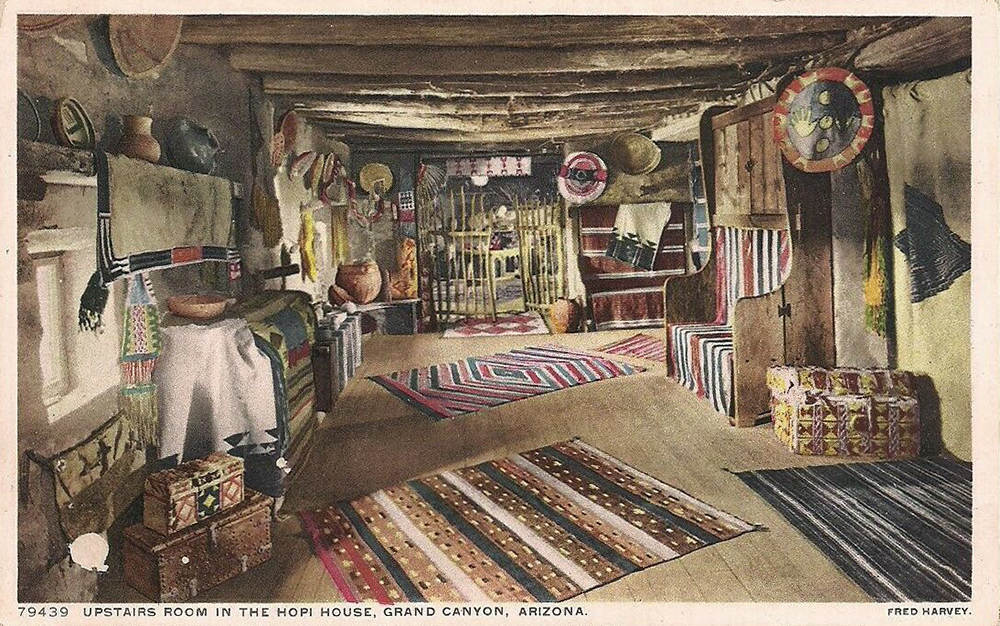

One of the shining stars in Harvey’s company was a young, enterprising man named Herman Schweizer, who managed the lunch counter at the Harvey lunchroom in Coolidge, New Mexico. On his off time, Schweizer bought arts and crafts from local Navajos, and then sold these items to diners at his eating facility. Fred Harvey’s daughter, Minnie Harvey Huckel, eventually caught wind of the activity and told her husband John Huckel, a Harvey executive. Impressed by Schweizer’s eye and enthusiasm for Native crafts, the Huckels proposed that Schweizer head up a new division, initially aiming to “furnish an attraction” for passengers on the Santa Fé line. So when the Alvarado Hotel went up, Colter set aside some space for a “curio shop,” which carried Navajo pottery, jewelry, and textiles. Near the Harvey House in El Tovar, visitors could purchase things made by people from the Hopi Tribe. “The Harvey system demanded the very best in rugs, jewelry, blankets, turquoise, beads, and silverwork,” writes Bryant, “and the large orders created employment for Native Americans and helped to preserve their ancient crafts.”

The Fred Harvey Company essentially branded Southwestern style for well-to-do Americans traveling westward along the Santa Fé railway. For many of these Americans, stepping into a Harvey House was the first time they encountered anything that could be described as having a Spanish, Mexican, or Native American aesthetic. Lingering memories of their experiences in these spaces — the luxurious hotels and dining rooms decorated with geometric weavings, pottery, beads, and silver antiques — spurred many into becoming lifetime collectors of such arts. Wealthy and powerful people, including William Randolph Hearst, bought things from the Alvarado shop for their private collections. Luminaries interested in Native American arts and crafts, such as Amelia Elizabeth White and Mary Hunter Austin, sought Schweizer for his opinion. Of course, Southwestern art and craft existed for centuries before such objects ever became part of a hotel or dining room’s decor. The Harvey company didn’t invent Southwestern style — they just introduced it to an affluent, largely white audience.

Jewelry in the Southwest stretches back thousands of years. The nomadic ancestors of modern Native Americans used jewelry for personal adornment, communication, and as symbols of identity, according to specialist writer Lois Sherr Dubin, author of North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment. These early jewelers ground seashells into flat discs and hung them from necklaces. They also decorated their clothes with carved wood, animal bones, and claws. But Native jewelry as we think of it today can be largely traced back to the intersection of Spanish, Mexican, and Native American culture during the mid-19th century. Around this time, indigenous people living on the Great Plains learned the craft of silversmithing from Spanish and Mexican settlers, many of the vaqueros — or cowboys — living in villages dotted around northwestern New Mexico. Following this tradition, Navajo and Pueblo silversmiths originally created things for horse bridles, bandolier bags, and tobacco canteens. Jewelry would soon follow.

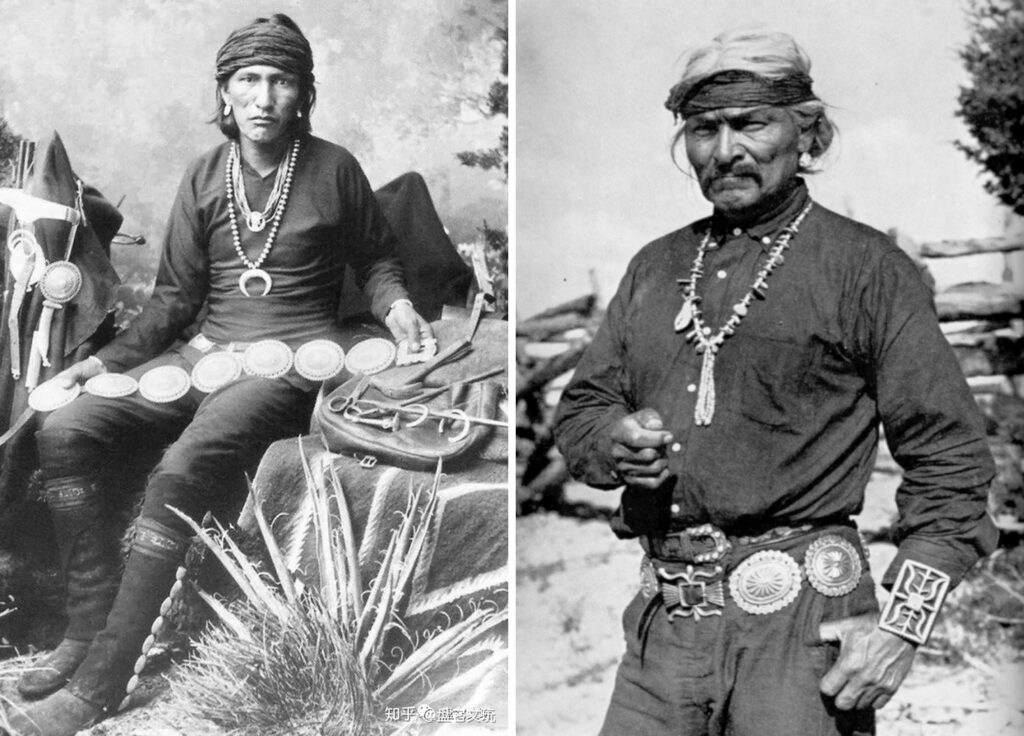

It’s generally recognized that the first Navajo silversmith was Atsidi Sani, a name that translates as “Old Smith.” Having learned silversmithing from a Mexican man named Nakai Tsosi (“Thin Mexican”), Atsidi Sani was famous for how he transformed silver into beaded necklaces, concho belts, and bridle bits made for horseriding. Before he passed away in 1912, he sat down and posed for a photo (pictured above on the left). Dressed in dark clothing and staring plainly into the camera, Atsidi Sani is surrounded by his creations, including a beautiful beaded necklace adorned with a crescent-shaped naja pendant. The shape is inspired by a talisman the Moors used to affix to their bridles as a way to ward off the evil eye. In the right-hand photo, we can see another maker wearing a concho belt, a shell necklace, and some sandcasted buckles that were made by pouring molten silver into earthen molds. (Also, check out that button-down collar!)

In the early days, Native silversmiths obtained their silver from English, French, and American fur trappers, who gave them silver dollars or pesos at trading posts in exchange for blankets, wool, or rugs. Plainsmen had little use for such coins, so they went home, smelted the silver into molten form, and laid the liquid down to dry. They would then cold hammer this material into armbands or bracelets, which were sometimes stamped with decorative motifs using railroad spikes or metal valves. At first, this jewelry was quite heavy, sometimes as heavy as a half-pound for a bracelet. Native artists at the time were producing only for themselves and people in their community, and everyone valued durability. Around 1890, native artists also started decorating their pieces with brilliant turquoise stones. But at the turn of the century, as tourists poured into the Southwest through the various railways, there was a paradigm shift — a market was beginning to form.

Ernie Lister, a Navajo silversmith who is trained in the old ways of making jewelry, says this history can be bisected into two phases. The first phase runs from about 1860 to 1910, when indigenous people were mostly producing jewelry for themselves. After 1910, as tourists came into the Southwest from the Midwest and East Coast, silversmiths produced for the market. In response to the demand, native artists made their jewelry lighter and thinner. They also stamped things with contrived “naturalistic” symbols, such as stars, bows, and crossed arrows, which spoke to the desire of tourists to consume things with their perceptions of indigenous ideals. When Lister asked his teacher, John Burnside — a fellow Navajo silversmith and medicine man — what those post-1910 motifs meant, Burnside answered plainly: nothing. “It’s what they wanted us to put on the jewelry, so we put those designs on there.”

Don Siegel, the founder of The Chipeta Trading Company, sells Native American jewelry made between the 1890s and 1940s, a period that stretches across these two historical phases. He mostly eschews Fred Harvey’s curio-shop jewelry, which he characterizes as “mass-produced.” Instead, he specializes in heavier and more unique pieces. “Every once in a while, I’ll come across a rare Fred Harvey piece, so I’ll purchase it. But it’s not what I primarily deal in,” he tells me. “Fred Harvey pieces are a different style. They’re often lightweight, have lower quality turquoise, and carry a lot of stamping, such as stamps with animal motifs. The jewelry I sell is more one-of-a-kind.”

Siegel has been passionate about Native American art for almost his entire life. As a teenager in the 1970s, a period when designer turquoise was all the rage, Siegel spent a lot of time at his uncle’s home. His uncle was a “picker” who spent Mondays rounding up horse saddles at the local arena and then driving to Navajo communities in New Mexico, where he traded these saddles for silver jewelry. Siegel admired these pieces in his uncle’s home, so he started to collect Native American art. He bought beaded moccasins, silver bracelets, and necklaces — a collection that grew and grew over the next forty years. When Siegel became CEO of his family’s motor oil company, he continued to collect. And shortly after retiring from the fuel industry, he founded Chipeta Trading Company, a passion project aimed at selling and promoting historic Native American art, including Southwestern jewelry, Plains beadwork, and Pueblo pottery.

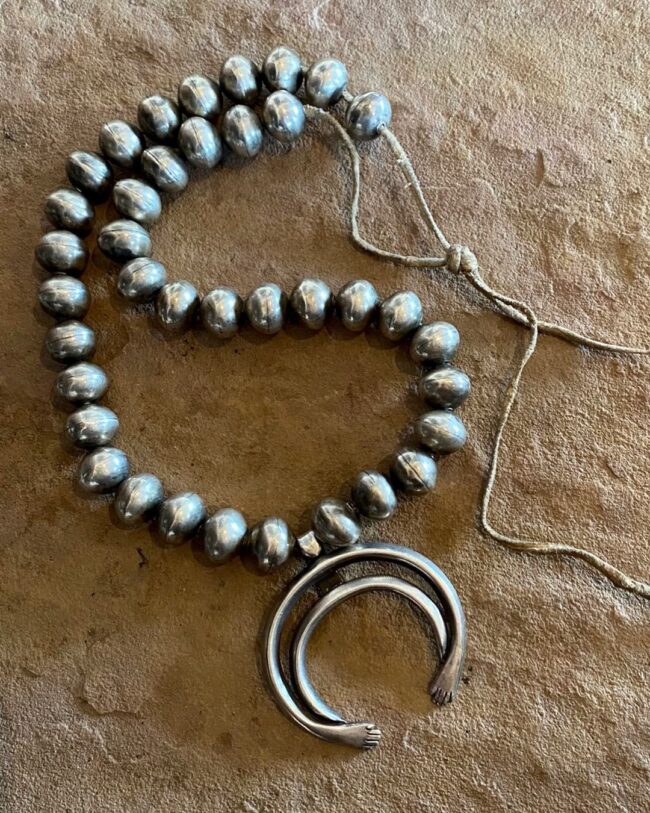

Since starting his company in 2005, Siegel has traded in everything from $500 silver cuff bracelets to $10,000 museum-quality showpieces. “It’s wearable art,” he says. “You’re wearing history.” His clients include Ralph Lauren, who has some of Siegel’s rare finds at his famous Double RL Ranch in Colorado. A cursory look at Chipeta’s website shows why. He has exquisite silver bracelets decorated with twisted wire accents and “robin egg blue” turquoise stones set in intricate motifs. There’s a silver Navajo concho belt estimated to have been made between the 1890s and 1910s (during the “first phase”). Siegel also has multiple squash blossom necklaces, a style that’s often considered the showpiece in many private collections because of how much time, skill, labor, and silver are required to make such precious pieces.

“The term ‘squash blossom’ is interesting,” says Siegel. “The design typically has three parts. The pendant at the bottom is called naja, which means crescent in the Navajo language. The symbol dates back to when the Moors put this shape on their horses’ foreheads to ward off the evil eye. When the Conquistadors arrived in the Americas, the Navajos were attracted to this symbol, so they later used it in their jewelry. Then you have the blossoms on the sides of the necklace, but they’re not actually squash blossoms — they’re pomegranate blossoms. A pomegranate almost looks like a pineapple, where you have leaves coming out at the top in three or four petals. Finally, you have the beads on the necklace, which are often decorated on up to four strands.”

Some years ago, Siegel started a new section on his website called “Southwest Style for the New Collector,” where pieces are priced at a few hundred dollars, rather than a few thousand. Siegel said he started this section because he started noticing that many of his social media followers were under the age of 35, and perhaps weren’t in a financial position yet to splurge for showpieces. “I wanted to create a new category to help people get started in collecting,” he tells me. Some of my favorite pieces in this section include the simple silver bangles and cuff bracelets, which I find go naturally with workwear-styled outfits, such as a ranch jacket paired with raw denim jeans and a heavy flannel shirt. If you’re into Wythe, Chimala, or RRL, these are natural accompaniments to many things likely already in your wardrobe. “For men, silver cuff bracelets and squash blossom necklaces are the easier styles to wear,” adds Siegel. “I wear six bracelets every day — four on one wrist, two on the other. I like how their weight makes me feel grounded. It’s like I’m wearing history. I also think silver beaded necklaces can look great with a tailored outfit or something more casual, such as jeans with a t-shirt.” Worn over the shirt or tucked inside? “Oh, always over,” he answers.

I ask Siegel about his private collection, expecting to hear of finely made, silver jewelry with intricate patterns still unseen. Instead, he tells me that he’s proudest of the older pieces, such as his very early concho belt, necklaces, and bracelets made sometime in the 1880s. “The older pieces tend to be very simple,” he says. “They were made from silver ingot and had minimal design elements. I’m also into brass bracelets from the 1850s, which were made before silver was widely available.”

For new collectors, Siegel gives three tips on how to get started in this field:

Find A Mentor. “Find someone willing to share their mistakes with you, so you don’t make them. I’ve made plenty of mistakes over the years. I’ve bought things that I thought were old, but it turned out they were new. You can buy silver ingot and old stamping tools today, and try to make things that look like they were made in the early 20th century. But there are telltale signs, such as wear patterns. It’s kind of like buying old jeans. You can wash them a certain way or hang them out in the sun, but if you have enough experience with this stuff, there are ways to tell if something is genuinely old.”

Don’t Be An Accumulator; Be A Collector. “When I first got into the business, I collected a lot of beadwork. When I was young, I was buying every pair of moccasins I could find. One day, I realized I had fifty pairs of moccasins, and they weren’t very good. Instead of buying fifty pairs of mediocre things, I should have bought one great pair. It’s the same with jewelry. Buy the best you can afford, and purchase the best pieces in each category, instead of many in the same.”

Read And Be Passionate. “Read three books for every piece of art you purchase. Study, study, study. I have a reading list on my website, where you can find reading recommendations.”

Readers interested in historic Native American jewelry can visit The Chipeta Trading Company’s website and follow them on Instagram. Some items can also be found at Standard & Strange. Notably, Chipeta donates its profits to various Native causes. Last year, that included Native scholarships, The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women, and several food banks serving indigenous people (e.g. The Food Depot, The Center Pole Food Bank, and Blessingway at Toadlena Trading Post). In the coming months, I’ll be writing about contemporary Native American jewelers and silversmiths, as well as Native-owned companies. In the meantime, you can find items made by living Native American artists at Shiprock Santa Fe and Maida.