On a warm afternoon in April 2009, the machines at the Southwick factory briefly stopped humming, as workers took a break from sewing fine men’s suits and naval officers’ uniforms so they could listen to two distinguished guests speak. The guests were Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick and Brooks Brothers CEO Claudio Del Vecchio, who were visiting that day to congratulate workers on their new facility. Just a year prior, Southwick, which was then located in Lawrence, Massachusetts, was on the verge of closing and having its operations moved to Thailand. It was then narrowly rescued by its largest customer, Brooks Brothers, who purchased the factory and relocated it just ten miles north to Haverhill.

Compared to its old location, the new Southwick factory had countless upgrades, including air conditioning and about $10 million in new manufacturing equipment. Instead of rolling out large, heavy bolts of cloth by hand, as workers used to do, this Haverhill factory had a computer-guided machine that effortlessly skimmed across a cutting table. When Del Vecchio promised in a speech that “Southwick’s best days are still to come,” hundreds of workers erupted with applause. “If it weren’t for him, we’d be in the unemployment line,” Regina Parisi, a stitcher, told The Eagle-Tribune.

Earlier this year, news leaked that Brooks Brothers was planning to close all three of its US factories — the suit factory in Haverhill, MA; shirt factory in Garland, NC; and necktie factory in Queens, NY — which spurred concerns about the brand’s future and its identity as a “made in America” label. As it turned out, Brooks Brothers was trimming its cost structure and preparing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. By the end of summer, Southwick’s equipment was sold off, and a Japanese company acquired the rights to its name. Meanwhile, the Garland shirt factory has been sold to a company specializing in manufacturing personal protective equipment. Such has been the long decline of Brooks Brothers’ American footprint. Forty years ago, nearly all of Brooks Brothers’ clothing was manufactured in the United States. Before their closure, these three remaining US facilities produced just 20 percent of Brooks Brothers’ inventory, which has mostly shifted to sportswear.

Much has already been said about the tragic loss of American jobs, which totaled about seven hundred between the three factories. But among trad purists, little love has been lost for an American brand that has long abandoned its American roots. Over the last thirty years, Brooks Brothers has chased trend after trend. Items such as luxury leather sneakers, stretch denim jeans, and contemporary fits and styling lead many to describe the new Brooks Brothers as “watered down Italian.” Consequently, many menswear enthusiasts have shifted their spending to smaller, more “authentic” boutiques such as J. Press, O’Connell’s, The Andover Shop, Cable Car Clothiers, and any place the stodgiest, round-toe Aldens can be found.

The internet has made it easier for people to track down niche labels that are faithful to a specific look, including unlined button-down collars, full-grain penny loafers, and “The Duke” Fair Isle sweaters made in the Shetland Isles. The public-facing side of this industry can seem vast and endless, but on the back end, there’s a relatively consolidated chain of suppliers who make for companies large and small. Many of these suppliers rely on a steady stream of large orders from giant corporations such as J. Crew, Ralph Lauren, and The Gap. When one of these giants falls, it sends ripples throughout the global supply chain, affecting whether smaller labels can get their hands on a specific good. Last month, one of the oldest silk mills still in operation, Vanners Silk Weavers, filed for administration.

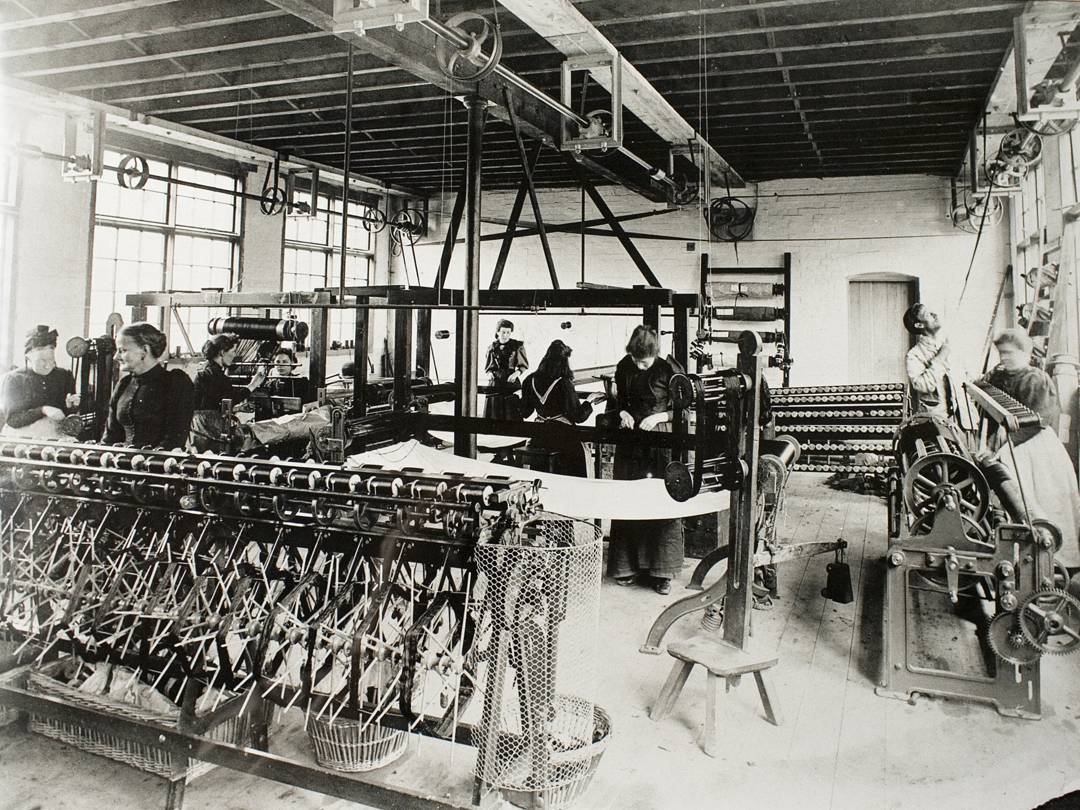

Nothing in the United States can really be compared to Vanners, as the company is older than this country itself. Its story stretches back to the early modern period of immigration to Great Britain and the first wave of globalization that swept across Western Europe. In the late 1600s, French Protestants facing religious persecution started arriving in Britain in large numbers after King Charles II offered them sanctuary. Many of these refugees, known as Huguenots, were from Normandy and Picardy, where they worked as silk weavers, throwers, and dyers. While the Huguenots eventually settled in different parts of Western Europe and even the United States, many ended up in the Shoreditch area of London, where they brought with them their tremendous silk weaving skills.

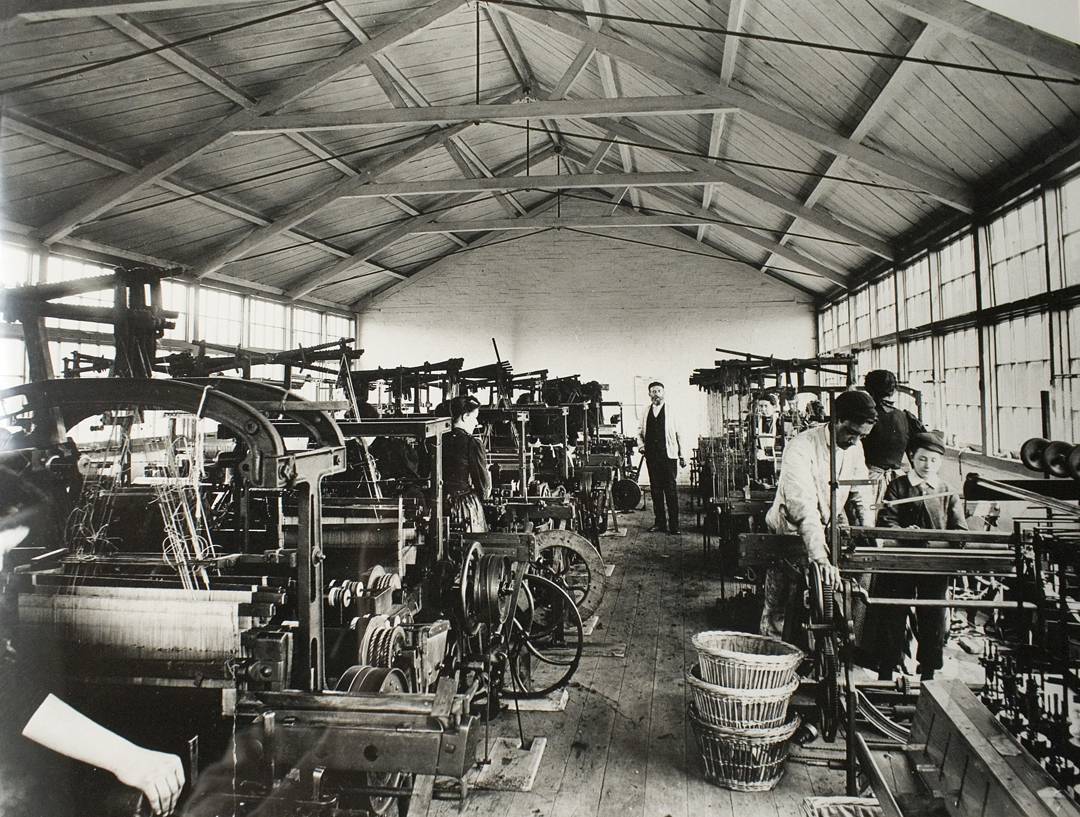

This eventually transformed Spitalfields into a major textile hub. (Like modern garment districts, it was also mostly staffed by immigrants, as French and Irish weavers worked side-by-side.) Among these Huguenots were the three Vanner brothers — all master weavers — who set up their family’s company in 1740. When life in Spitalfields became too expensive, they moved to the Suffolk-Essex border area in 1860, where there was already an established wool trade, a natural complement to the silk industry. Their city, Sudbury, has become renowned for its silk production. Sudbury silks have been worn by the Queen at her coronation, royal brides, and former First Lady Michelle Obama. Yet, there are only four Sudbury mills left standing. There’s Stephen Walters & Sons (which also houses David Walters Fabrics), Gainsborough Weaving (which primarily supplies furnishing fabrics), Humphries Weaving (which produces small bespoke lengths), and, of course, Vanners.

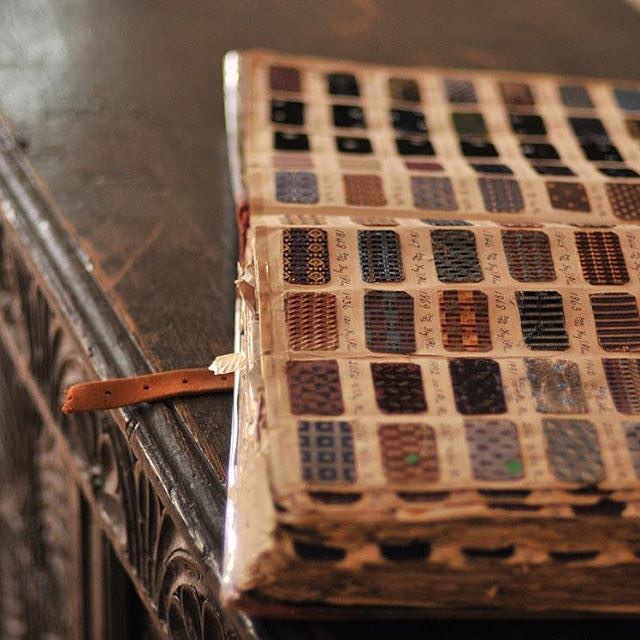

Even if you’ve never heard the name Vanners, you almost certainly have a bit of their silk. Over the last hundred years, they’ve become one of the best-known industry names for high-end necktie silks, including the regimental stripes and jacquards specially woven for schools, clubs, and companies. They’ve supplied silks to Ralph Lauren, Brooks Brothers, Burberry, Eton, and Isetan. They also sell silk to Savile Row tailoring houses and boutique labels such as Drake’s, Vanda Fine Clothing, and HN White (the third being a sponsor on this site).

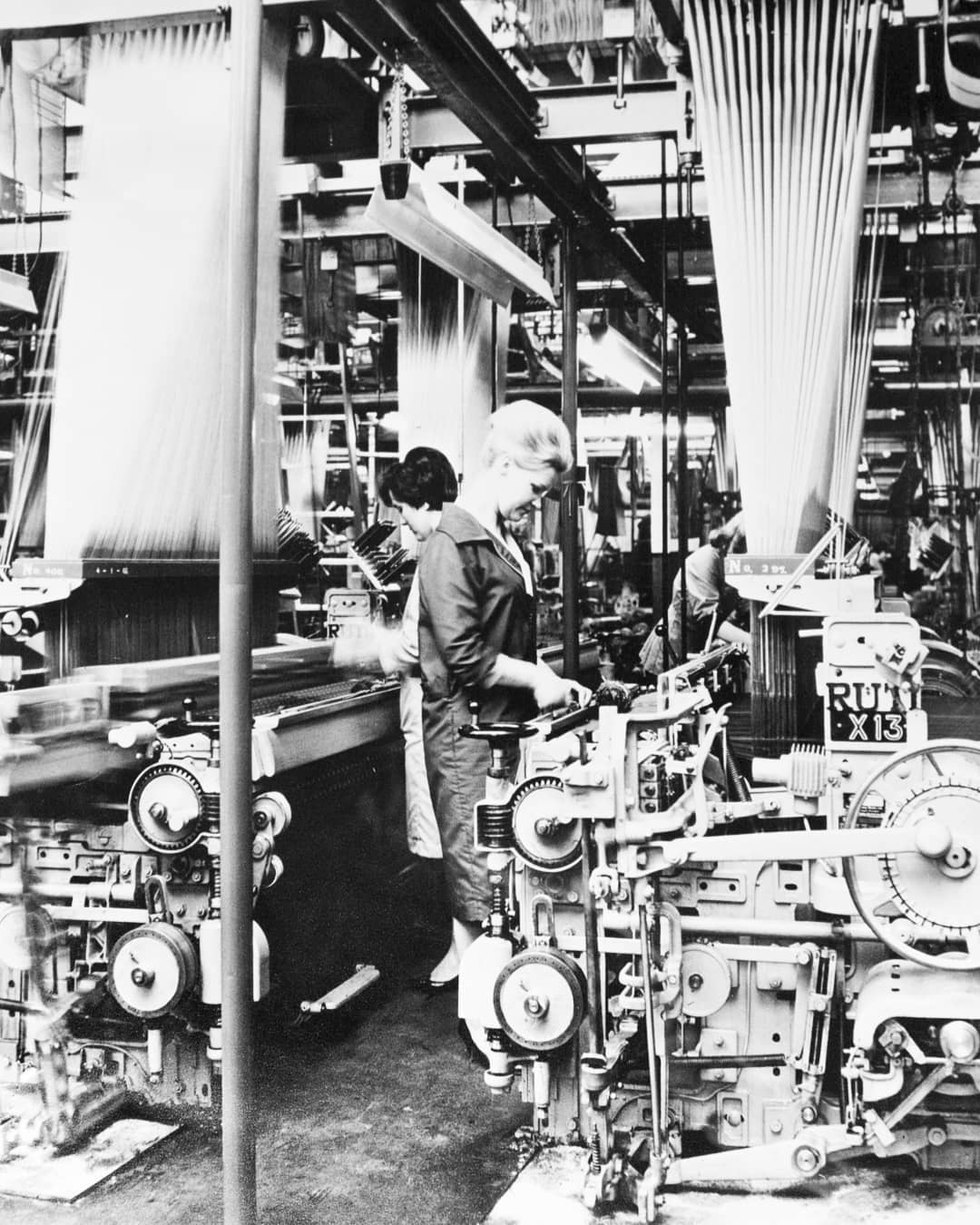

Laura Gore, Vanners Managing Director, tells me that the mill is famous for its color. “We only purchase the highest quality twist of silk,” she explains. “We also use special looms — 350-end looms — which means the warp is very dense. Other mills may use something like a black warp with a red weft when weaving fabric, which dulls down the color. But we can use a red warp with a red weft. It’s what we call a ‘true color’ or ‘pure color.’ We pack so much silk into our fabrics, they end up having a certain quality, luminosity, and color. They’re unrivaled.”

Gore estimates that about 80 to 90 percent of the mill’s silk is ultimately used to make neckties, which has left the company overly exposed to the casualization of men’s wardrobes. As men have been shedding traditional neckwear, the firm has seen sales fall from about £9m in 2015 to £5m/£6m last year. “That was causing a bit of financial constraint,” Vanners Chairman David Tooth told The East Anglian Daily Times. “Nevertheless, we were carrying on, and (while) I wouldn’t say things were wonderful — we hadn’t actually lost any customers — it’s just all our customers were doing far less.”

The slippery slope may have started as a gentle decline, but things began speeding downhill this year at a breakneck pace. With the closure of airport stores run by fashion brands such as Burberry, Prada, and Thomas Pink, along with other store closures worldwide, Vanners saw their 30% decline spread over five years sharpen to a steep 70% drop this year alone. Earlier this year, the directors had to furlough half of their 64-person staff, but even that wasn’t enough to save the company. The critical blow came this summer when Brooks Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, leaving Vanners with a debt. Although Brooks Brothers has been since sold off to Authentic Brands Group and the mall owner Simon Property Group, Vanners has not been able to reestablish a contract. “That was like a really big blow to us,” Tooth said.

Vanners’ decline came quite suddenly about five years ago, closely tracking, perhaps not coincidentally, the timeline of when Brooks Brothers went into the red. Ten years ago, Vanners’ turnover was about five times what it is today, and Brooks Brothers constituted about 30 percent of their orders. Gore tells me that business was quite good ten years ago, when tailored clothing was more popular. Then things went very sour, very fast. “For a mill, there’s little warning,” Gore explains. “Brands get to see what’s going on in stores on a day-to-day basis, so they can better prepare for these things. But for a mill, we’re on the back foot, so a brand might come in and say they’re only going to order half of what they normally do for that season. You can’t prepare for something like that. Ten years ago, even if people wanted to source something from China, they would come to us first. As time has gone on, brands have become savvier. They may use us for the luxury part of their line, and then get stuff from China and Italy for the rest of their production.”

On menswear blogs and forums, people often segment the market between the niche and mainstream, as though there was a bright dividing line between the two. In reality, these two ends of the market are sometimes tied together through a shared supply chain. When the International Textile Group shuttered their Cone Mills White Oak plant in 2018 — the last industrial-scale selvedge denim mill in the United States — it was reported that only a small fraction of the mill’s operation was actually dedicated to selvedge denim. The plant’s real business came from larger brands who have slowly moved their production offshore, as textile and apparel tariffs have been gradually lifted through a series of free trade agreements. When White Oak permanently closed, small brands such as Raleigh Denim, Tellason, and Left Field had to scramble to find a new supplier. The same has also happened to those small trad brands that used to rely on Southwick and Garland. Their production at those factories was only possible because of the existence of Brooks Brothers.

In a blog post, longtime White Oak customers Tony Patella and Pete Searson of Tellason reflected on the plant’s closure: “If White Oak is the size of a football field, the Draper looms that make the selvedge denim take up the space of half of an end zone. The mill depends on selling a large volume of fabric produced on their modern looms — the exact type of fabric large brands and retailers use. As these brands and private label producers moved their production out of the US, there was no way they would ship fabric from North Carolina to Bangladesh, China, or Vietnam.”

Behind the facade of a seemingly endless number of retailers and brands, there sits a somewhat more consolidated global chain of spinners, weavers, finishing houses, and specialized factories. In the last year, parts of this web have wobbled. “The problem is how interconnected we all are,” Lindsay Taylor of Holland & Sherry said in a Permanent Style post. “We’re all dependent on WT Johnsons for finishing, for example, so until they’re up and running we can’t produce anything.” When Brooks Brothers filed for bankruptcy, I wondered if the new company owners would still source the same wonderfully nubby, light blue oxford cloth (which I’ve heard used to come from Japan). If they discontinue it, it’s unlikely that smaller companies who normally rely on fabric remnants will be able to commission the same runs.

Vanda Fine Clothing, a Singapore-based producer of handmade neckties, started in 2011 with Vanners as their supplier. “Stephen Nixon, the former sales director who left the company earlier this year, was particularly kind to us and didn’t mind that we were a tiny outfit,” says company co-founder Gerald Shen. “We’ve purchased silks from some of the finest weavers in the world and still find Vanners’ repp silks to be really special. They have a nice dry, full hand and are virtually indestructible as far as ties go. Their 350-end jacquards are equally excellent and have a nice depth of color and richness of hand.”

Gore tells me that Vanners is currently talking to potential buyers, who may be taking over the firm and leading it in the coming year. It’s possible that the ink on the contract is drying at the time of this post’s publishing. If so, I’ll update it soon with news. In the meantime, you can find Vanners silk neckties at Vanda Fine Clothing and HN White. At Vanda, just search for the terms block repp, double bar repp, and sawtooth. Some of the striped Shantungs, jacquards, and bi-color wovens are also from Vanners (I particularly like the simplicity of this summer tie). Over at HN White, you can find a beautiful dark olive tie that would be the perfect complement to a brown tweed, and a striped navy and teal tie that will go with just about anything.

Update: Vanners has been purchased by Roger Gawn, owner of brands such as Swaine Adeney Brigg, Herbert Johnson, and more.