There are two stylized images of life in Southern California. One is an exotic fantasy that was first communicated through surf films such as Gidget (1959) and Beach Party (1964), where the entire Golden State was distilled to the few beach towns that radiate up and down the coast. In these wholesome coming-of-age-stories, there’s always a group of athletic teens with sun-bleached hair that laugh and smile as they get into freewheeling antics at some late-night beach party. Sometimes there’s a romantic misunderstanding or a rivalry with a vicious, but hilariously stupid, group of bullies, but their lives are otherwise uncomplicated. As the endpoint of westward expansion in the United States, California is the geographical and symbolic opposite of the East Coast. Whereas New England’s gloomy weather inspires a kind of pensiveness, California is a place where you can live without a care, sometimes not even a thought, in the world.

The other representation of Southern California is darker, grittier, and more dystopian. In his book City of Quartz, historian Mike Davis paints a picture full of Dickensian extremes. Downtown Los Angeles has a monumental architecture glacis that segregates the rich from the poor. Wealthy neighborhoods in the canyons and hillsides are isolated behind guarded walls and electronic surveillance systems, while homeless people sleep on the street in a district known as Skid Row. In Hollywood, celebrity architect Frank Gehry apotheosized the siege look with a library that resembles a military compound.

Over in Watts, there is a series of shopping centers modeled on panopticon architectural systems, which English philosopher Jeremy Bentham surmised would help institutions control large groups of people with minimal resources. Seven-foot-high, wrought iron fences surround the largest shopping center while a private security force patrols the perimeter, and an LAPD substation is located inside the central surveillance tower. (Developer Alexander Haagen defended his design by saying the fence is inspired by a similar barrier that surrounds the USC campus, which separates students from community residents. That barrier has since only grown with new ID checks, fingerprint scanners, license plate readers, and surveillance cameras). This is a picture of a city girded by fear, and, as William Whyte observed of social life in cities, fear invariably ends up proving itself. In his chapter titled “Fortress LA,” Davis writes:

Such dystopian visions grasp the extent to which today’s pharaonic scales of residential and commercial security supplant residual hopes for urban reform and social integration. The dire predictions of Richard Nixon’s 1969 National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence have been tragically fulfilled: we live in “fortress cities” brutally divided between “fortified cells” of affluent society and “places of terror” where the police battle the criminalized poor. […] The occasional appearance of a destitute street nomad in Broadway Plaza or in front of the Museum of Contemporary Art sets off a quiet panic; video cameras turn on their mounts, and security guards adjust their belts.

In reality, Southern California exists somewhere between these extremes. Davis is a serious historian and social thinker, but his book has also been rightfully criticized by those on the political left, right, and center. L.A. Weekly editor Jill Stewart called Davis a “city-hating socialist,” while geographer Cindi Katz characterized his apocalyptic views as masculinist and flattening. In a book review published at The New York Times, Bryce Nelson accused Davis of being as provincial as the Angelenos he looked down upon. “The author makes little mention of the climate, scenery, economic zest and diversity that have made Los Angeles what he calls ‘the fastest growing metropolis in the advanced industrial world.’ […] He often writes as if he did not know that the problems of crime, pollution, racism, and poverty characterize every large American city and, indeed, cities elsewhere. He sometimes writes as if Los Angeles, sheltered by the ocean, mountains and desert, existed alone.”

These two stylized images of life in Southern California don’t fully represent reality, although they’re valid in certain pockets of the region. Still, they exist in our consciousness as two of the more unique genres of Americana, which are so familiar to us that we only need to see a few images to know what they’re referencing. The idea of sun-surf culture is represented through photos of bronze-colored bodies rollerblading around Venice Beach and Santa Monica. This is the marketing fantasy of Hollister, PacSun, and Vans, which have made Southern California a cornerstone of their identity (Hollister even has California as its tagline, even though the teen retailer was founded and continues to be headquartered in Ohio). For these brands, coastline attire is as uncomplicated as the leisurely lifestyle associated with it. Board shorts represent a kind of carefree optimism, not just because they’re suited to California’s weather, but because they show you never worry about anything, not even your appearance.

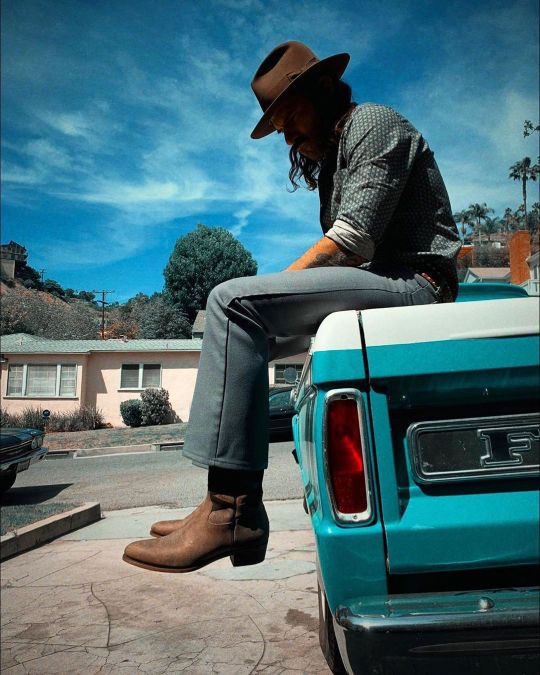

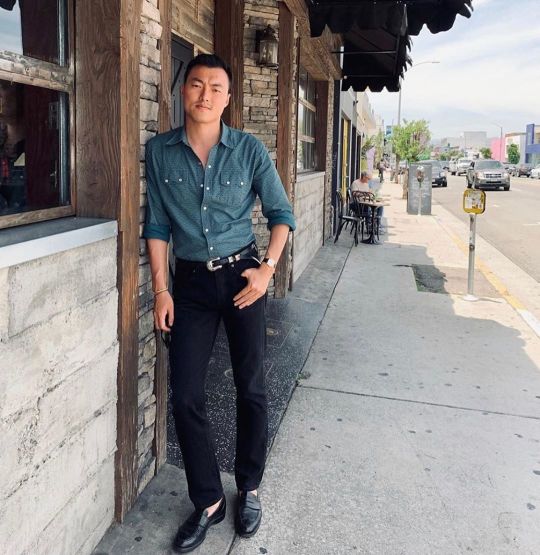

The darker, grittier view of city life manifests itself through a panoply of other wardrobes. My favorite is the urban cowboy: a brooding figure that meshes the ranch hero with the L.A. gigolo. This workwear style is distinct from the Rugged Ivy uniform of the East Coast or the heritage-heavy rodeo look of the Southwest. It relies on slim-tapered black jeans, fitted chambrays, and loose tees layered underneath trucker jackets. To distinguish it from your everyday Levi’s lookbook, you often have layers of sleazier elements, such as chunky jewelry, side-zip boots, long point collars, 1970s style tailoring, and questionable leather outerwear. Oversized sunglasses with gradient lenses finish the look. This is the menswear equivalent of a 1960s Cadillac Eldorado or the country-rock tunes of Waylon Jennings playing on the Sunset Strip.

You can see this look in classic L.A. movies: Two Lane Blacktop (1971), Straight Times (1978), American Gigolo (1980), Cutter’s Way (1981), and To Live and Die in L.A. (1985). Crime dramas and neo-noir films that take place in Los Angeles often involve a straitlaced detective trying to crack some Pynchonesque conspiracy. If the film is from the 1970s or ‘80s, the detective will usually be dressed in a semi-fashion-forward suit from that era, often something with extended shoulders and wide lapels, rather than the conservative Ivy styling of New England poetry professors. The more colorful and compelling characters usually come in the form of some anti-hero: a lowlife criminal, a cocaine trafficker, or an inveterate gambler trying to catch a break. These characters are often dressed in some kind of working-class top: snap-button Westerns made from thin-waled corduroy or sturdy denim, silky rayon shirts unbuttoned to the navel, or vacation-style shirts with trippy psychedelic patterns. These men sport lacquered-looking waves, a dark caterpillar mustache, and thin gold necklaces dangling from their neck.

This anti-hero shows up elsewhere, too. In the film Drugstore Cowboy (1989), which takes place in the Pacific Northwest, Bob Hughes (Matt Dillon) wears sweaters with a plunging neckline, plaid Western flannels, and black leather rancher coats. The remorseless Texas hitman Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) looks like the grim reaper in his all-black denim trucker outfit in No Country for Old Men (2007). At the end of Goodfellas (1990), Lucchese crime family associate Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) is on his way to pick up drugs from his Pittsburgh associates as he’s driving down a New York highway. Nervous from cocaine use and insomnia, he becomes paranoid when he spots a helicopter flying overhead. In this scene, Hill is wearing one of the cooler outfits in the film: a chain-striped top that’s somewhere between a Ban-Lon polo and a button-front shirt, which is decorated with a thick banded hem and long collar points. He pairs it with charcoal bootcut slacks, black shoes, and gold jewelry.

Some real-life figures also wear this look well. Sebastian and Sergio Guardì, the two Italian brothers behind Barbanera, like to mix corded Western shirts with jeans, Western boots, and tailored topcoats. “I love cowboy style, but adding a Western-inspired piece to your look doesn’t mean you have to look like a cowboy,” Sergio once told me. Then there’s Tom Waits, the hoarse troubadour who embodies the spirit of drifters who drive along the American highway and hang out with short-order waitresses, beatniks, and barflies. The best modern-day rep for this deliciously lecherous aesthetic, however, is Ben Cobb, the editor of Another Man and a favorite subject of many street style photographers. In a feature published about him in The New York Times, Cobb says he just loves 1970s style. “One person’s sleaze is another’s romanticism,” he says.

If you’re thinking about giving this a try, No Man Walks Alone, a sponsor on this site, is currently running a pre-order on their Valstar jacket, the Clint. The model is exclusive to their store and comes from Valstar’s archive. It’s a hybrid bomber jacket with a Western yoke, large collar, and corduroy lining. No Man Walks Alone is offering it in brown and black suede until Sunday, and the orders will be delivered sometime this fall. I think both colors look tremendous, but I’m partial to the black suede version because I think it’ll go well with slim black jeans and a pair of black side-zip boots. Depending on the vibe you want to create, you can wear it with a white tee, blue chambray shirt, or a black Western button-up. Greg at No Man Walks Alone tells me the jacket runs true-to-size, and while orders are final sale, they can do size exchanges upon delivery in the fall (assuming your size is available).

Some other wardrobe options:

Outerwear: Self Edge has a ton of outerwear that would suit this look, including a suede Iron Heart trucker and some new tea-core jackets from 3sixteen. Todd Snyder’s Italian suede Dylan trucker isn’t as heavy or rugged as the Iron Heart version, but this look isn’t necessarily about heavy workwear anyway. The snap buttons will be easier to use than the donut-shaped buttons on Iron Heart’s jacket, but plain snap buttons also have a smooth, unadorned dome, which may leave something to be desired. Division Road, a sponsor on this site, has the same Iron Heart trucker in brown suede, along with Dehen mechanic jackets and Private White VC black wool bombers. For a budget-friendly option, it would be tough to beat Lee’s Storm Rider or a Czech liner jacket. Lee’s Storm Rider has a slightly shorter, boxier cut and extended shoulder line than Levi’s Type III, and I think it looks more attractive when worn. French chore coats are also a good standby (and often better vintage).

Tops: Start with a fresh pack of white tees from 3sixteen, Lady White, or Levi’s Vintage Clothing. Hanes Beefy-T is also a reliable, budget option, although they shrink a little more with time. Additionally, I’ve been digging vacation-style shirts, rayon shirts, camp collar shirts, and snap-button Western styles. This season, RRL has a boxy, camp collar plaid flannel in a dusty pink color (I bought one last week and love it), as well as a linen-viscose blend shirt made with a turn-of-the-century desert print. Over at Imogene + Willie, you can find waffle-knit thermals, raglan-sleeved sweatshirts, and faded denim Westerns. Guys who obsess over details will probably appreciate the unique flap pockets on Stevenson Overall Co. and Freenote’s Western shirts. J. Crew’s Wallace & Barnes line also has reasonably affordable Japanese chambrays this season, so long as you purchase them on sale (they’re currently $90). For graphic tees, I’m partial to the country-rock themes over at Midnight Rider. (Again, it’s all about Waylon Jennings).

Pants: I’m not daring enough for 1970s style bellbottoms, but I do like a pair of fitted jeans or five-pocket cords. As a color, black works exceptionally well since blue jeans and brown five-pocket cords have a safer Americana vibe (whereas black feels more rock ’n roll). I like COF Studio’s M1 and M2 cuts, which are slim without being Hedi-style skinny. They also have a slightly higher rise, which will protect you from the dreaded plumber’s crack when you sit down. For five-pocket cords, I like Kaptain Sunshine, although they’re sold out the moment. Todd Snyder may be worth a spin.

Work Boots and Canvas High-Tops: Pretziada makes a chunky, rubber-soled workboot modeled after something shepherds supposedly wear somewhere in the Mediterranean countryside. I like them for their unique silhouette, although, without longer lacings, they can be a bit of a pain to put on. Viberg produces a modern, upgraded version of the American trench boot, which was worn during the Second World War. Side-zip styles can be had through Viberg, Lucchese, and Kapital (the last of which is pictured above). You can purchase Kapital’s side-zips through Fashionship in Japan, but it may be easier and more straightforward to proxy them through San Francisco’s Cotton Sheep (I’m a size 9D and take a size 3 in those boots). For affordability and simplicity, it’s hard to beat a pair of 1970s Chuck Taylors. They came out during this Golden decade, after all.

Accessories: Companies such as Moscot and Jacques Marie Mage both have retro-inspired eyewear frames that would go wonderfully with this look. Jacques Marie Mage’s line is inspired by L.A. car culture and workwear, which makes them a perfect accompaniment with side-zip boots and Western shirts. Moscot’s Shtarker has the sleaziness of the 1970s without (too much) of the baggage. I also think this look benefits from having a bit of jewelry. Self Edge carries cuffs, necklaces, and rings made by Native American craftspeople, as well as a line of kintsugi-inspired rings from Kei Shigenaga. Lastly, men have different comfort levels when it comes to wearing fragrance, but if there’s ever a time to smell like birch tar, it’s when you look like city cowboy. Try Andy Tauer’s L’Air du Desert Marocain or Lonestar Memories. The camphorous smell pairs well with the smoky pollution Davis describes in his book.