For the past few years, at the start of every season, I’ve made it a tradition to publish a post about things I’m excited to wear. These posts are a deliberate shift away from the conventional notion of “wardrobe essentials,” a concept that has, in many ways, lost its relevance as people lead different lifestyles. They also allow me to just talk about things I’m excited about. I think that emotional connection—rather than a coldly calculated and rational approach about supposed “essentials”—is a much better way to build a wardrobe, as it makes you think about what you’ll love wearing ten years from now. I’ve been encouraged by readers who tell me they find these posts useful in helping them build a wardrobe. So here are ten things I’m excited to break out this season, along with a Spotify playlist at the end that will hopefully set the mood.

THE POLO COAT

Like many things, the game of polo is an international phenomenon with cultural origins now long forgotten. The modern version of the game was first played in Manipur, India, where locals called the fist-sized wooden ball pulu, a Tibetic term later anglicized to polo. In the mid-19th century, British cavalry officers picked up the sport in India, imported it to England, and then spread it around the world during the height of empire. It’s through this intoxicating mix of sport and nobility that polo has become such fertile ground for menswear. The game has given us the button-down collar, jodhpur and chukka boots, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso, and the most recognizable menswear logo. It has also given us the polo coat—the most American of dress outerwear styles.

When you look at the polo coat, you’re looking at the confluence of three cultural streams. There’s the game itself (Indian in origin) and the semiotics of English nobility (stemming from an uncomfortable relationship with hereditary peerage and British imperialism). Then there’s the story of how American clothiers gave this British garment its definitive form.

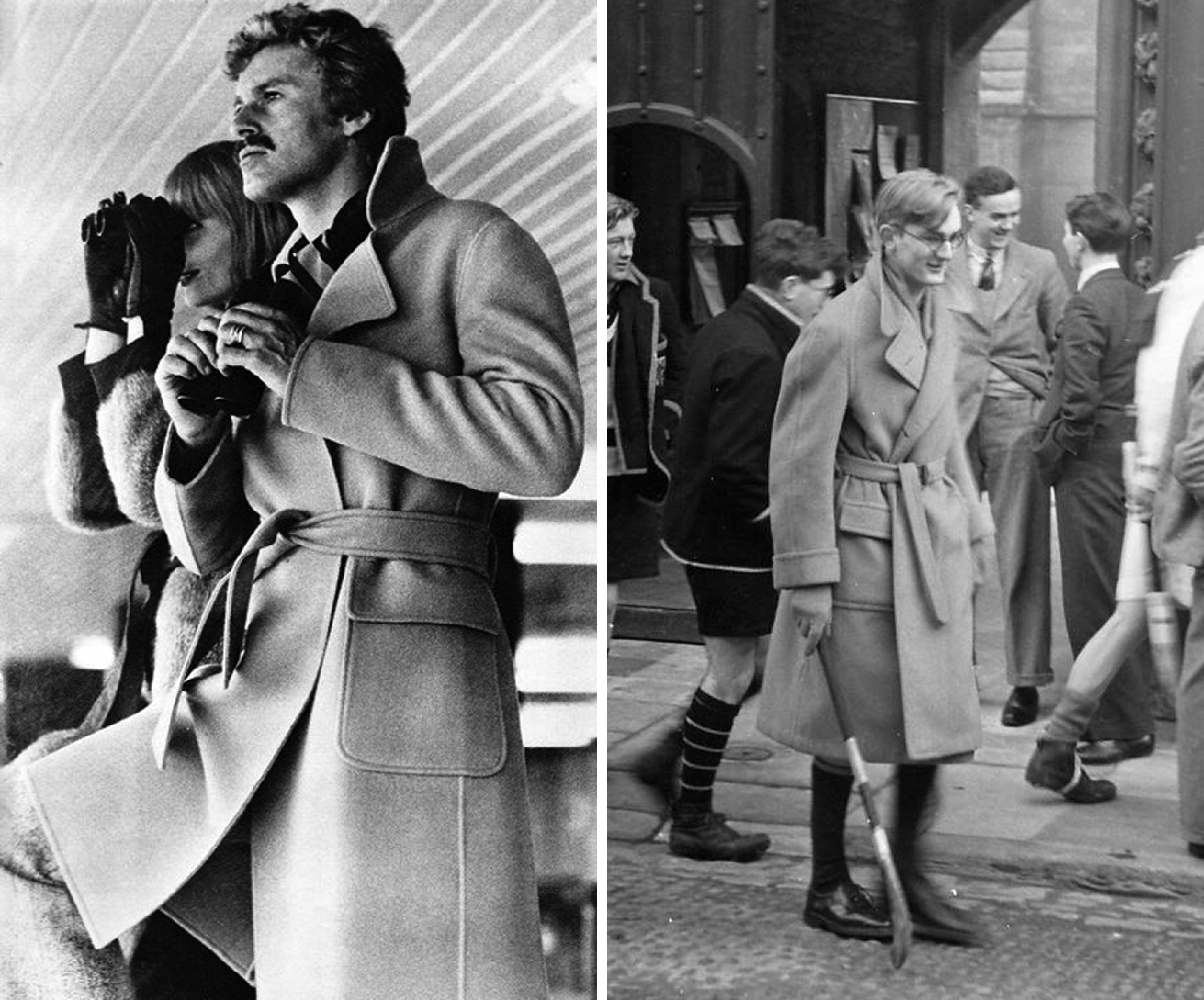

The polo coat started life as the “wait coat,” a wrap-style coat that English polo players threw over their shoulders to keep warm between periods of play. The wait coat was little more than a glorified bathrobe. It was a button-less design with a self-fabric belt tied around the waist, finished with an Ulster collar to frame the wearer’s facial features. I’m sure someone in England must have thought to put buttons on it at some point. But when you compare traditional English overcoats to the polo coats sold through Brooks Brothers and J. Press, you can see why the Platonic version of this garment is so distinctively American. Some parts of this design are standard: the double-breasted 6×2 closure with turnback cuffs, envelope pockets, set-in sleeves, a Martingale back, and either a peak lapel or an Ulster collar. But what makes a polo a polo—and not just a tan DB overcoat—is the dropped buttoning point that elongates the lapel line. The lower buttoning position also gives this coat that cavalier swagger that’s so emblematic of American style, stretching from Marlon Brando’s rebel pose in The Wild One to youthful streetwear styles that emerged by the end of the 20th century.

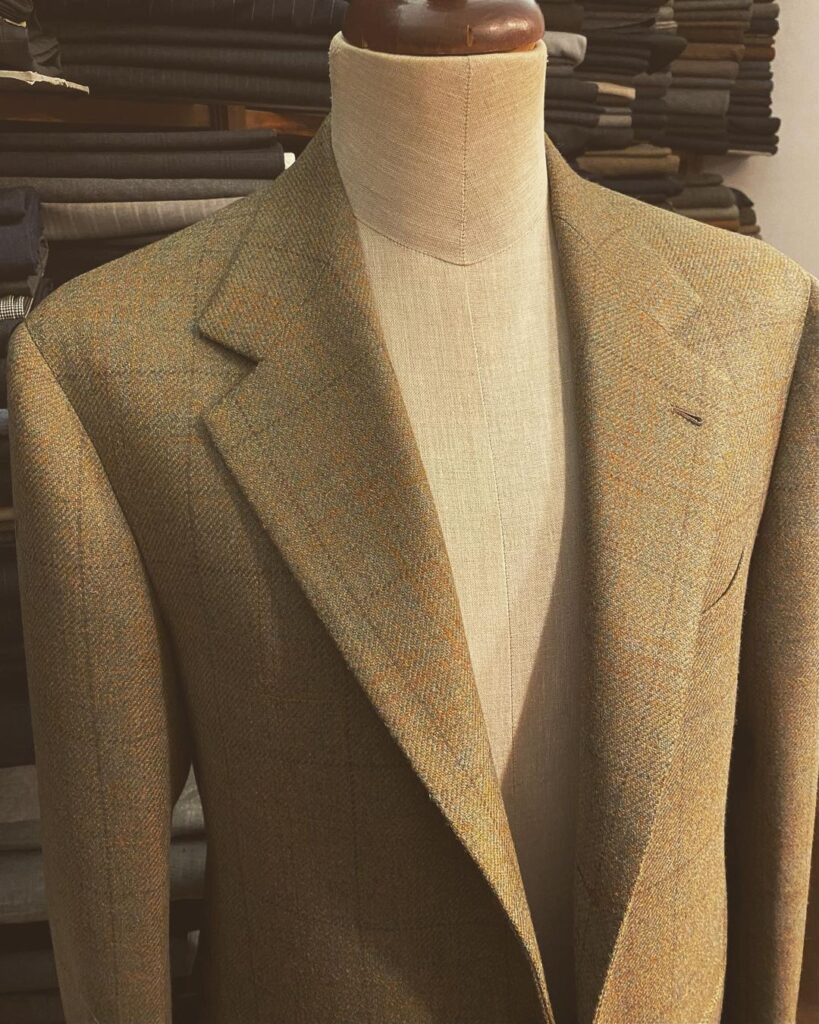

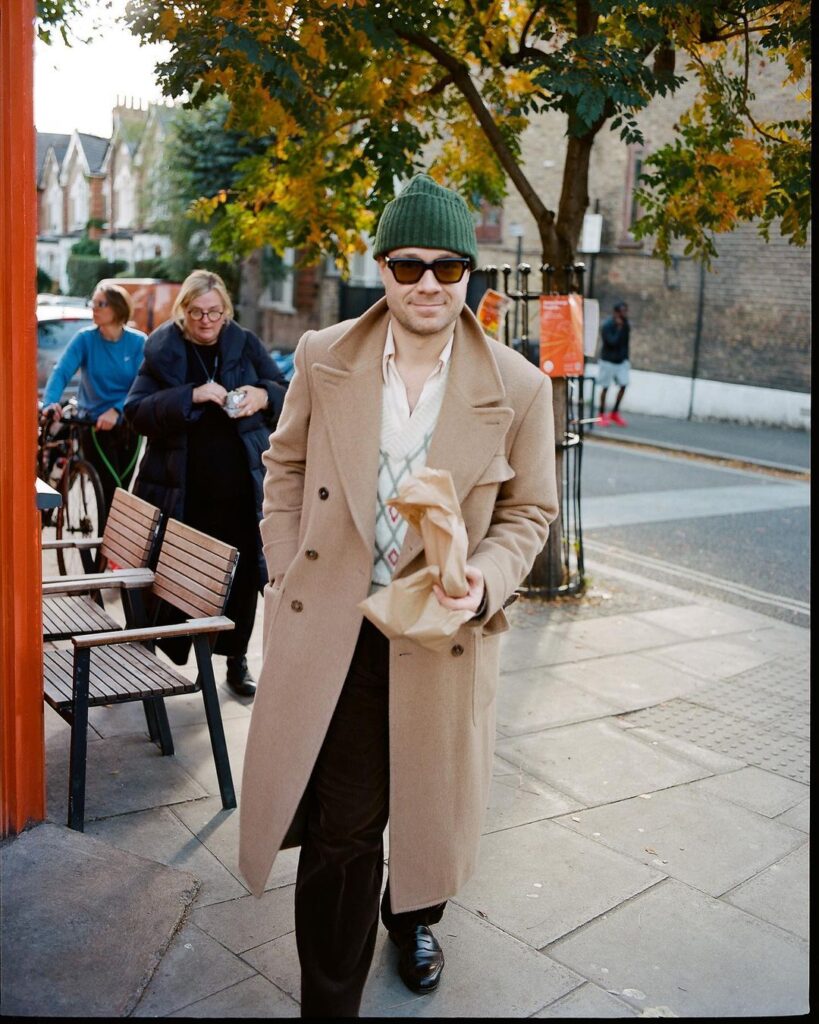

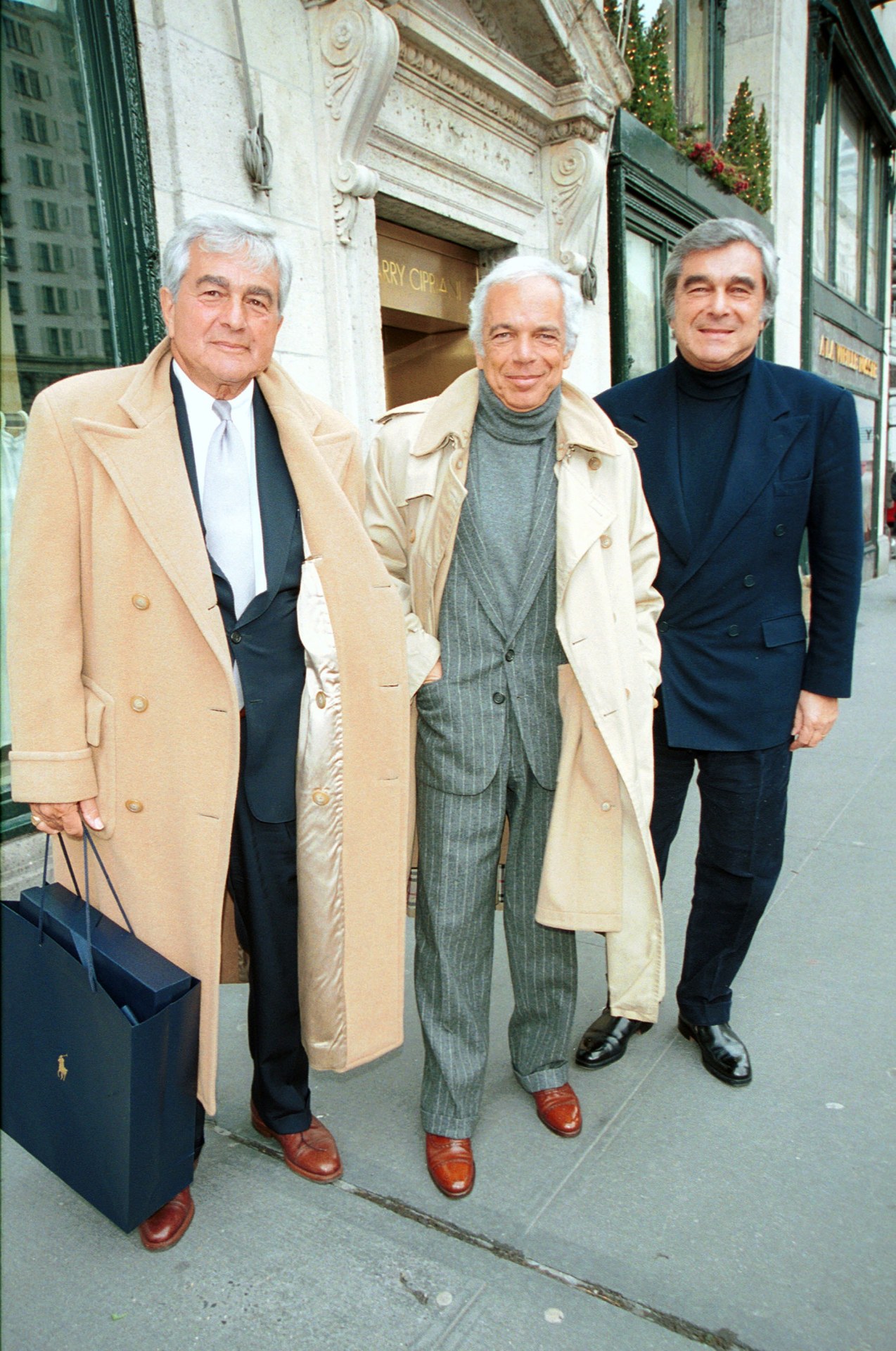

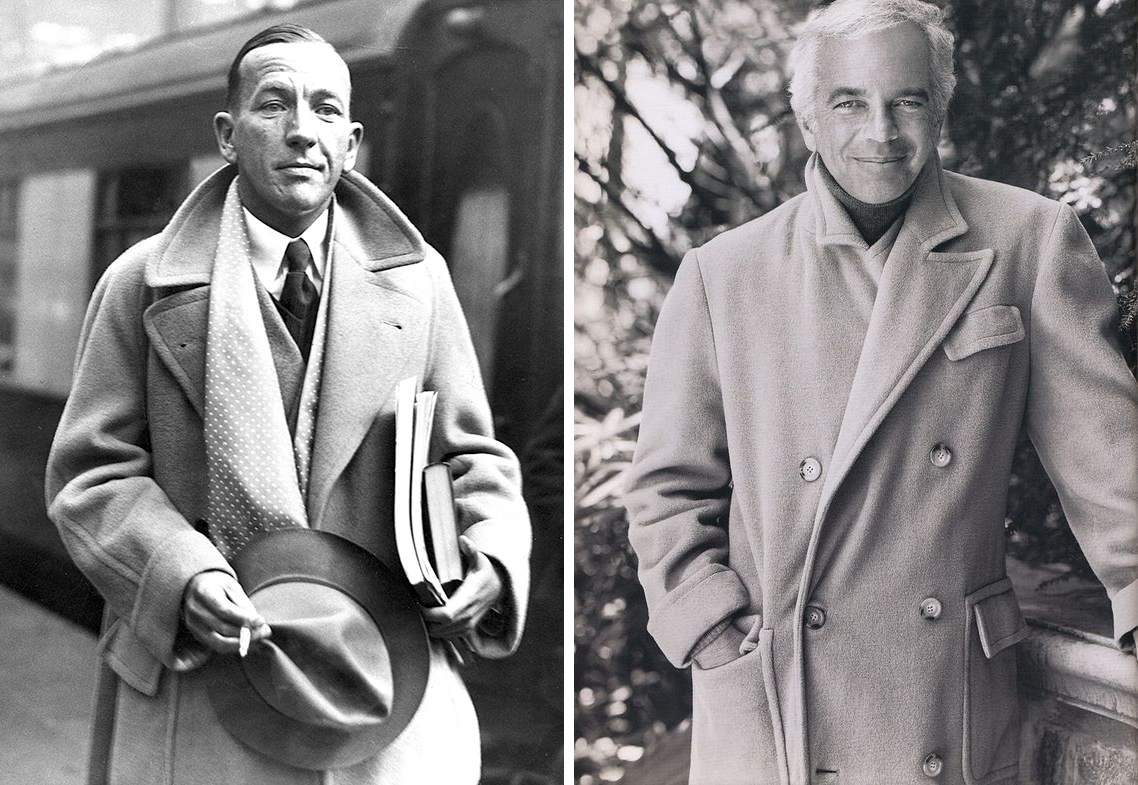

The thing I’m most excited to wear this season is a bespoke polo coat from Steed. It’s made from a now-sold-out pure camelhair overcoating from Harrison’s of Edinburgh. Pure camelhair, like pure cashmere, wears very warm for its weight but can be a bit delicate, which is why you often see it mixed with wool. I went for something in a slightly darker shade of tan, suspecting that it’ll be easier to wear than the popular blonde hue, and opted for peak lapels because the style reminds me of Ralph Lauren. If you like popping your collar from the back, like Noël Coward at Waterloo Station upon his return from the United States, then an Ulster collar may be better.

When commissioning this overcoat, I wanted it to look like the Ivy versions I’ve admired for much of my life, but I ran into a dilemma. Most bespoke tailors finish their garments by hand, usually with a pick stitch that results in a series of soft dimples. Factories, on the other hand, typically finish their garments by machine. AMF and Complett machines can imitate the look of a hand-executed pick-stitch, but whereas hand-finished ones result in soft dimples, machine-made ones often look like they were done with a nail gun. Then there’s the machine-executed lockstitch that’s sewn a quarter-inch away from the lapel’s edge. This results in a harder, straight line and plumper edge—a look typically echoed by the lapped seams running across the back, shoulder, and pocket flaps. American tailoring has always been more machine-made than its Savile Row counterparts, which is why Ivy-styled overcoats are often distinguished by that hard line that runs parallel to the lapel’s edge.

I suggested to Steed that they finish my coat by machine, but when my cutter, Edwin, brought it up to his finisher, Pam, she winced. Pam felt this would be like painting a mustache on the Mona Lisa, so she came up with a clever solution: by hand finishing the coat with a backstitch, she was able to imitate the unbroken line that you see on traditional Ivy-styled polo coats while still preserving the integrity of a handmade garment. I thought it was an innovative solution and a testament to Steed’s integrity that they would do everything by hand, even when machine-finishing would have been easier (and originally requested by me, the customer).

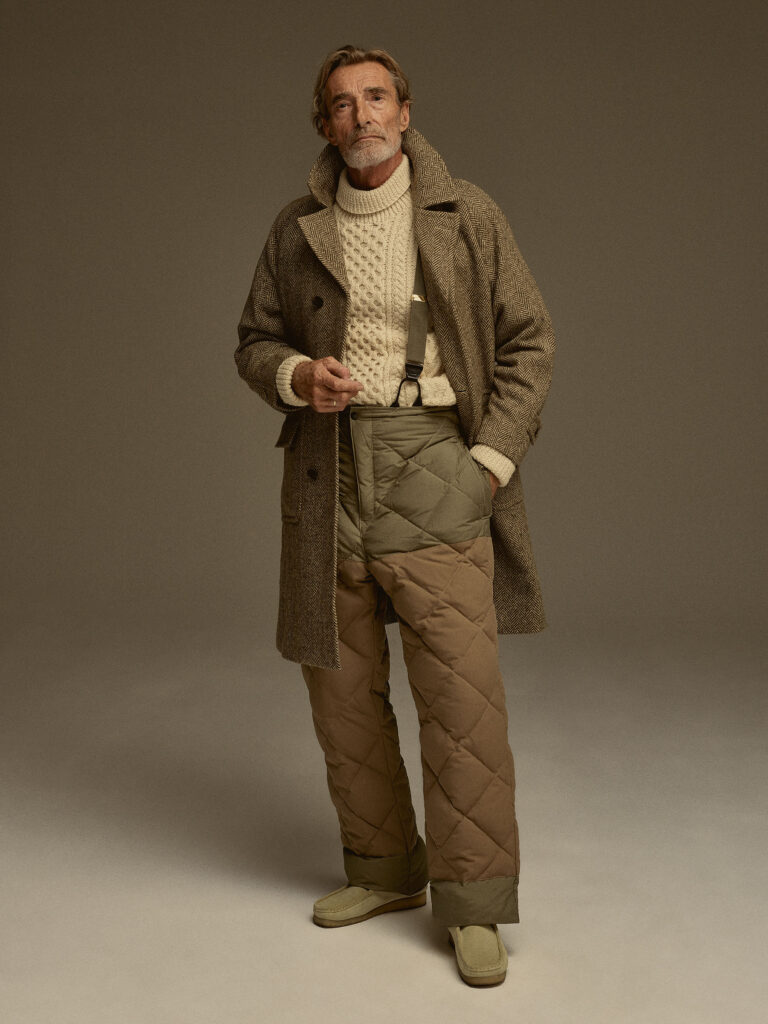

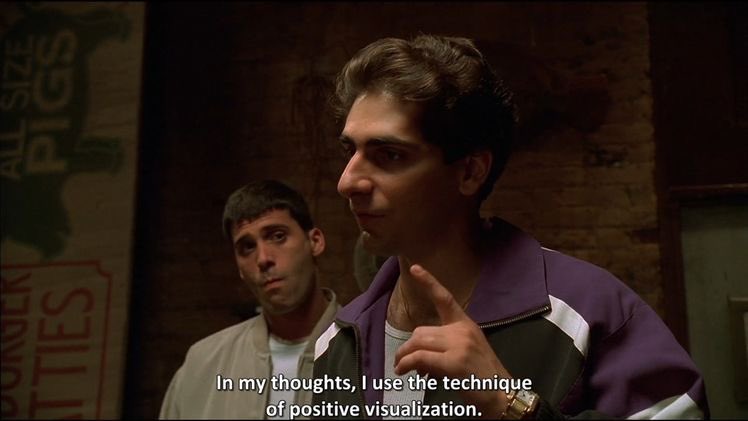

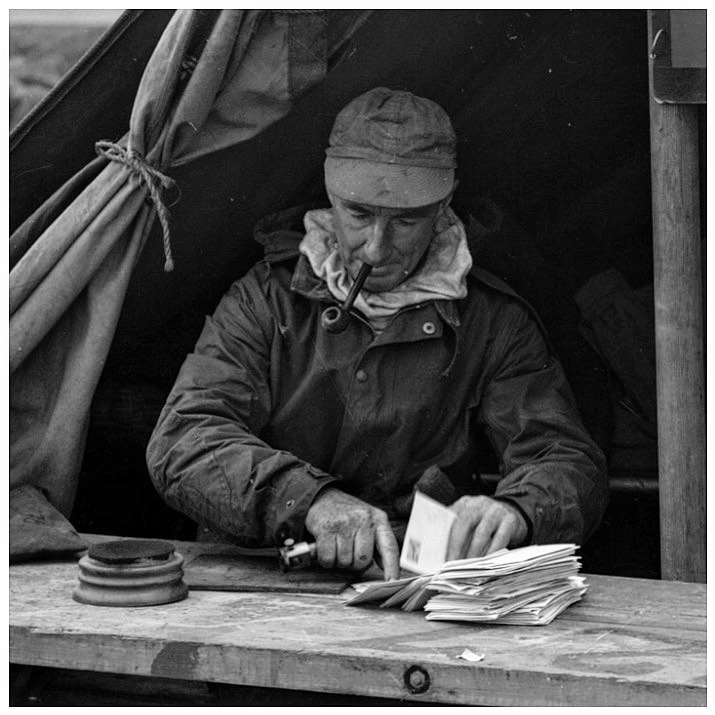

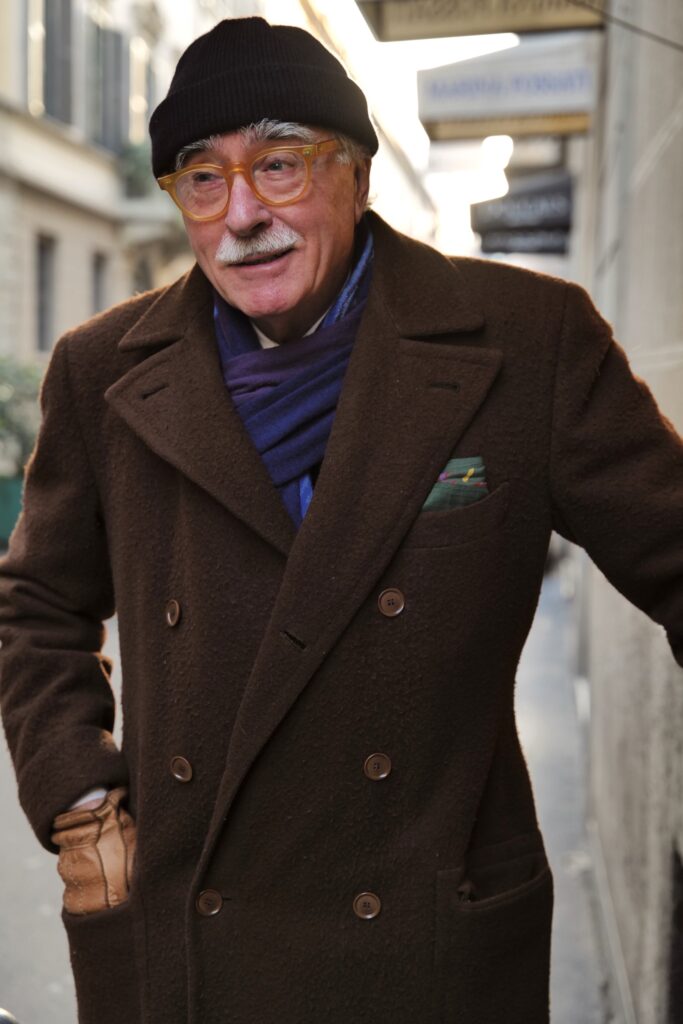

Wearing a big overcoat is the single easiest way to look good this fall. Whether you get a polo, an Ulster, or a raglan-sleeved Balmacaan, this is something you can throw over almost anything: chunky Arans paired with cavalry twills, spongey Shetlands teamed with five-pocket cords, or even a stained sweatshirt worn with jeans. Dress outerwear gives you many of the benefits of tailored clothing without making you look overdressed. I recommend getting something big. If it is a polo, then the sort of silhouette that Paulie Walnuts or Johnny Sack wore on the Sopranos. If it is a Balmacaan, then the sort of oversized, long thing that feels more like a comfort blanket than outerwear. Slim, short overcoats may be more practical if you drive, but they lack verve.

Options: Ralph Lauren, Brooks Brothers, O’Connell’s, The Anthology, Todd Snyder, Spier & Mackay, Cordings, J. Press, Bryceland’s, Saman Amel, Lemaire, Stoffa, Berg & Berg, De Bonne Facture (old and new season), Kaptain Sunshine (one of the best designs on the market, I think), Frank Leder, Sartoria Carrara, Olderbeast, Private White VC, J. Crew, Drake’s, Buck Mason, and Uniqlo.

UTILITY PANTS

During the 2020 lockdown, while stuck at home and with no one to impress, I pulled out a pair of vintage painter pants I had bought two years earlier. When I first got the pants, I tried them on at home, and after determining I just looked like a house painter, I threw them into the back of my closet and never thought about them again. But during that slow year, I pulled them out during a closet clean, snipped off the ends to give them a raw hem, and wore them with whatever I had on for the day: an old flannel shirt with a Lee 101J trucker, a Shetland knit with a vintage fishing jacket, or a stout sweatshirt with a tailored topcoat. I found that they surprisingly go with anything.

I know I’m not saying anything novel here. Carhartt double-knees have been trending for a few years now, and much of menswear derives its history from work purposes. But painter and carpenter pants are a wonderful alternative to blue jeans if you’re stuck in a style rut. They’re rugged and washable, look better with age, and add something interesting to an outfit without being the center of attention. You can even repurpose the hammer loop to securely hold a glass of merlot during this fall’s garden parties.

Over the summer, I bought these Ralph Lauren carpenter pants, and they’re my new favorite thing. The double-knee design incorporates itself into the pocket bag stitching, an interesting detail that differs from most double-knee pants, where you have a straight line across the thigh. The pre-distressed fades aren’t ideal, but I’ve found that they look passably authentic once they align with the folds you eventually create. I’ve been wearing mine with flannel shirts, a Lee 101J trucker jacket, all-black Blundstone boots (on sale right now at Amazon), and a Polo USA baseball cap. A pair of white Dickies painter pants would also look great with a rugby shirt (e.g., J. Crew, Withernot, or Patagonia’s 50th-anniversary rugby) or a stout sweatshirt paired with Wallace & Barnes blanket-lined chore coat (with one of J. Crew’s coupon codes, this may be one of the better “affordable” outerwear options this fall).

Options: Ralph Lauren, Dickies, Stan Ray, Carhartt (vintage, new, or WIP), Glenn’s Denim, Rudy Jude, Imogene + Willie, Skinner American Goods, Cottage Industry, Orslow, Indigofera, The Real McCoys, Kapital, and Miles Leon

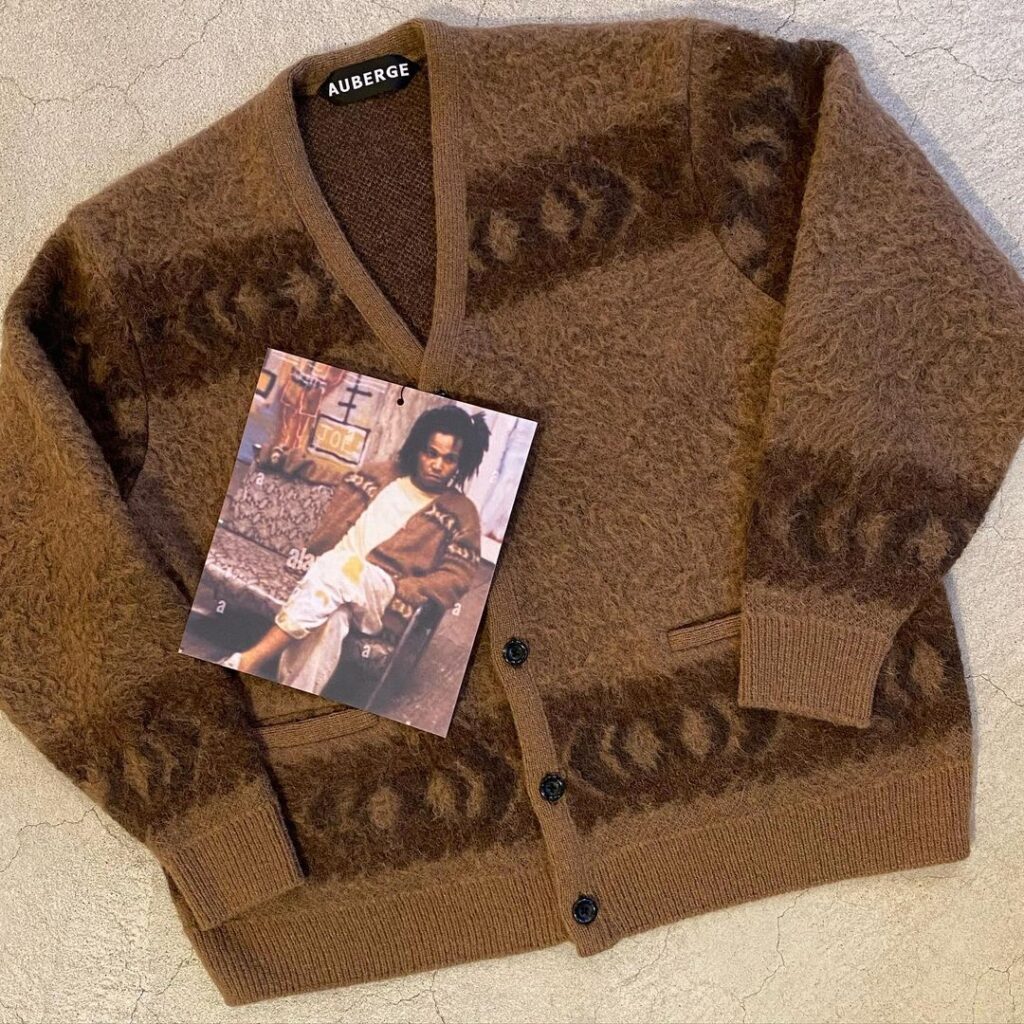

TEXTURED KNITS

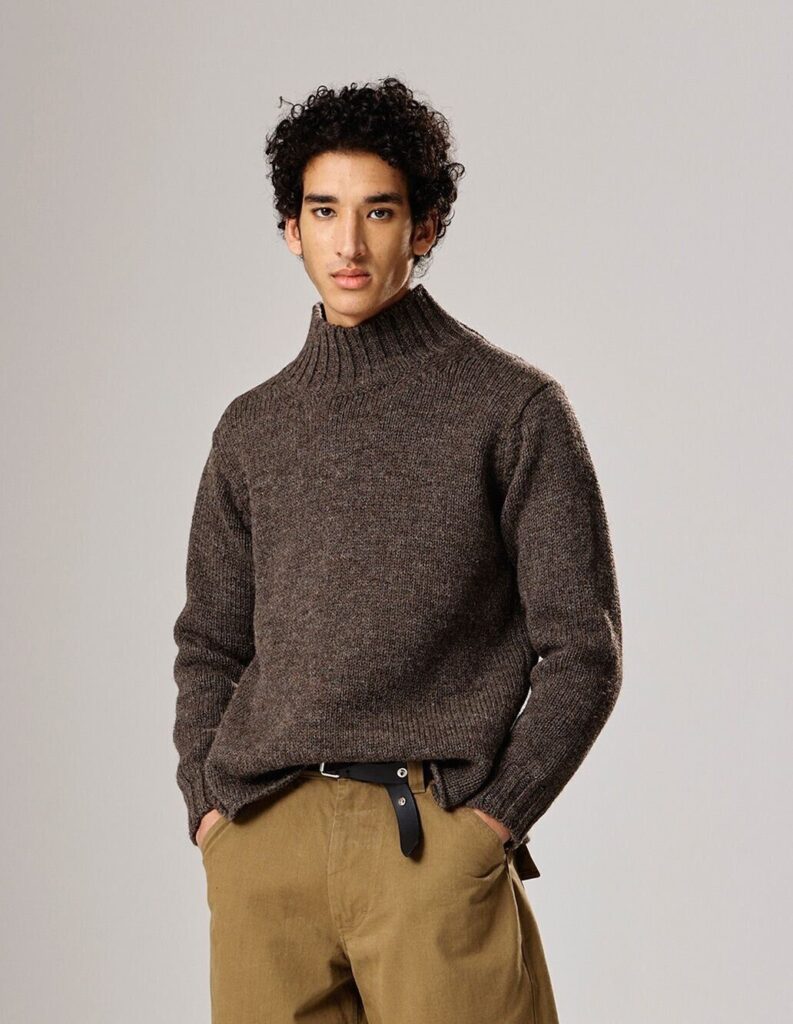

I’ve always believed that knitwear is better when it’s textured. A plain, smooth merino can look good under a sport coat, but when paired with casual outerwear or worn on its own, it feels like a missed opportunity. Instead, I think those outfits benefit from having a bit of texture, especially to help push them out of the realm of business casual. The world here is your oyster: spongey Shetlands, chunky cable knits, Shaker sweaters, Arans, guernseys, and unique designs abound.

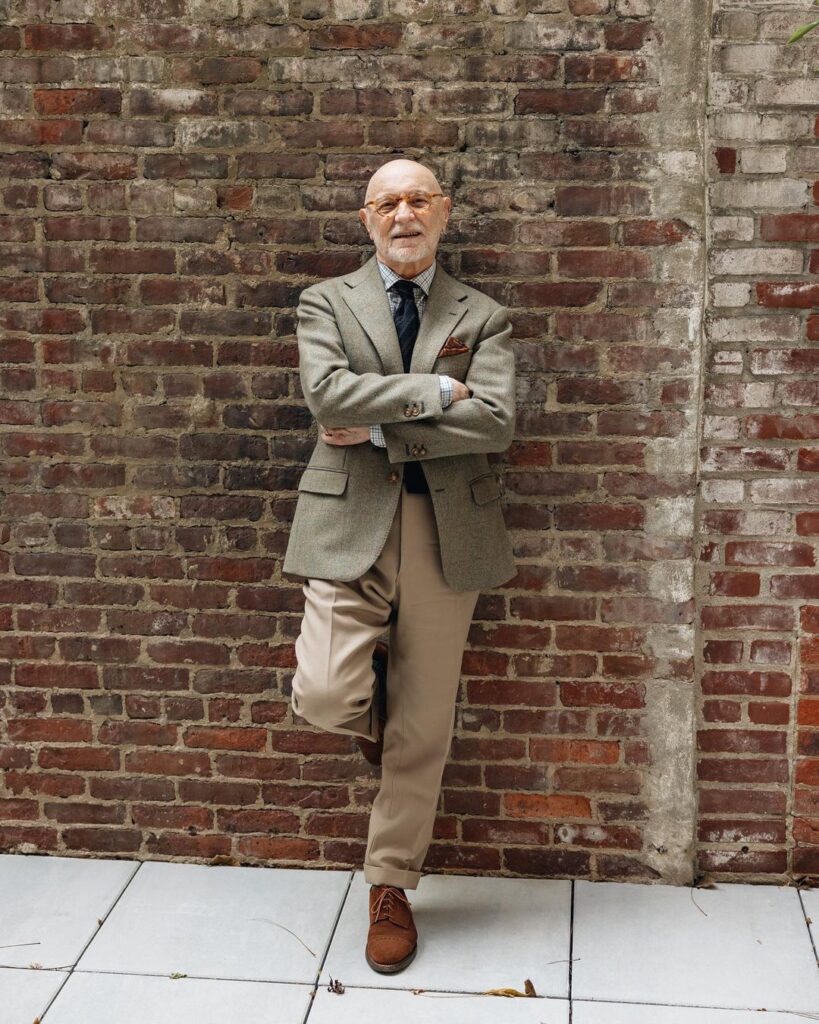

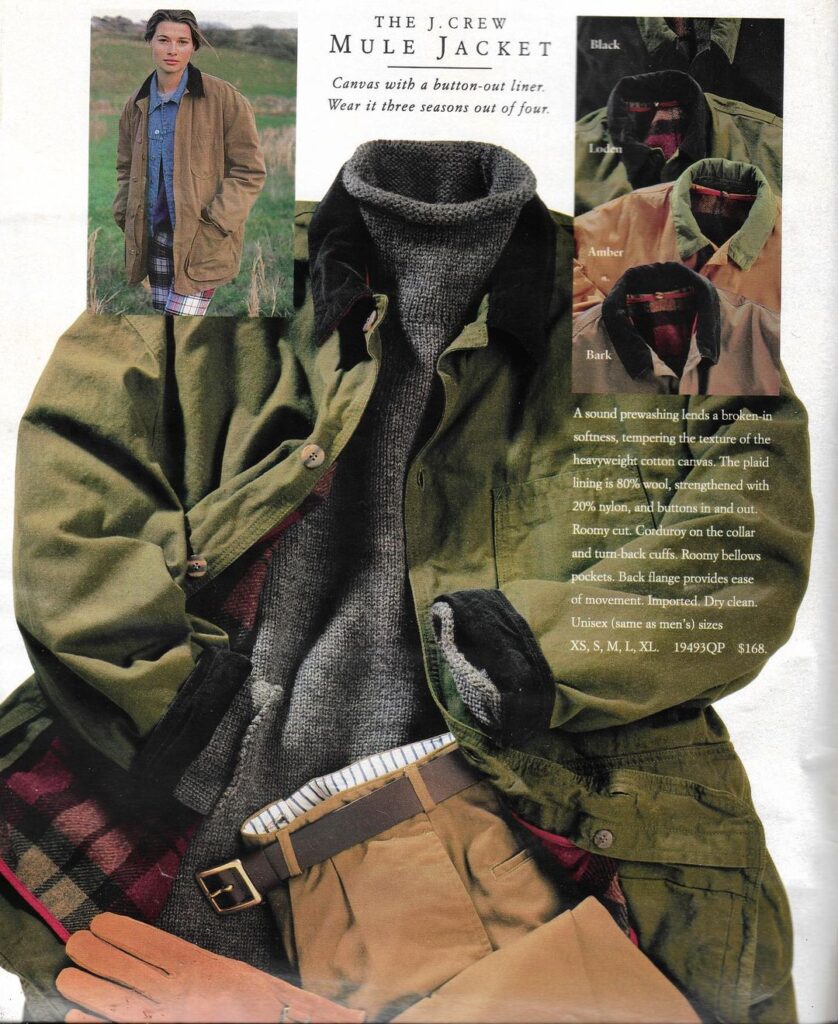

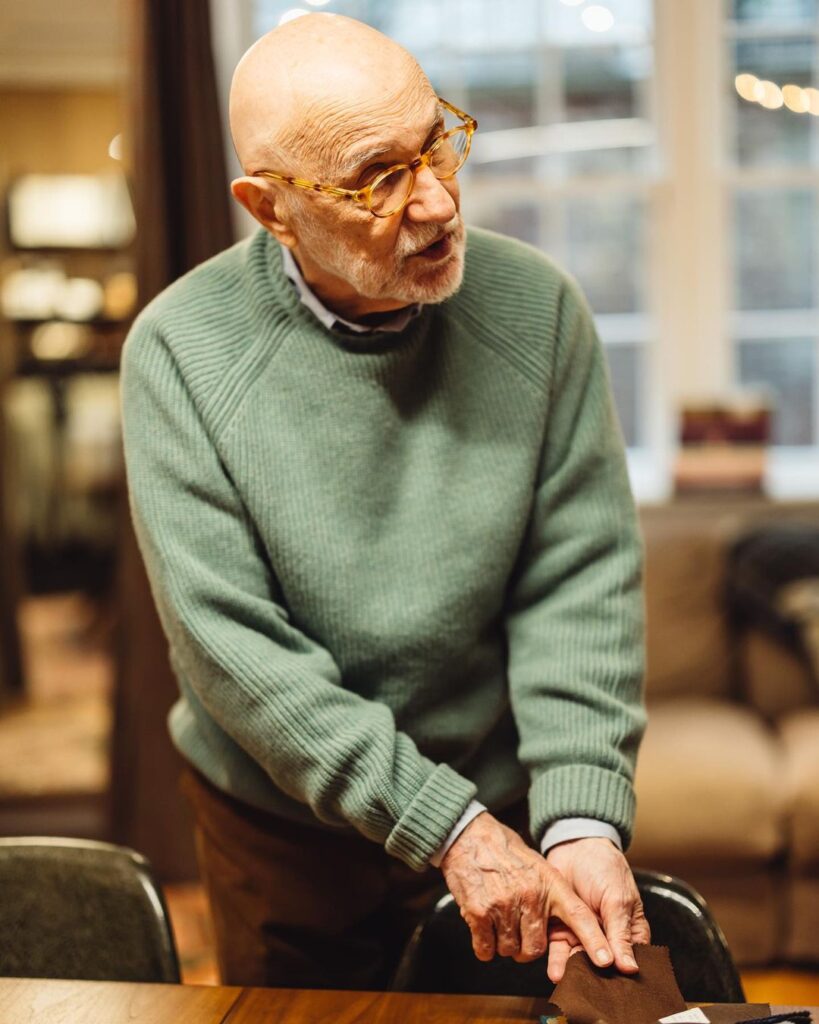

Last year, Bruce Boyer kindly gave me a Shetland from his wardrobe. When he told me he was sending something, I thought it would be one of the 2-ply Shetlands you can find stacked in piles at trad shops, but it turned out to be a sweater from Bosie’s Blue Mogganer collection—a vintage-inspired line of 4-ply sweaters, some made from a softer Shetland yarn. They’re a bit too chunky for trim Italian sport coats, but they fit comfortably underneath drape-cut English tweeds and look even more at home under roomy outerwear. Bosie’s 4-ply Shetlands come in suitably autumnal colors such as burnt ochre, moss green, and the shade of brown found on a pheasant’s belly. O’Connell’s also has some handsome Shetlands this season made from undyed, natural-colored yarns, which show off the variegated color of sheep’s wool. Wallace & Barnes has something similar in fisherman form.

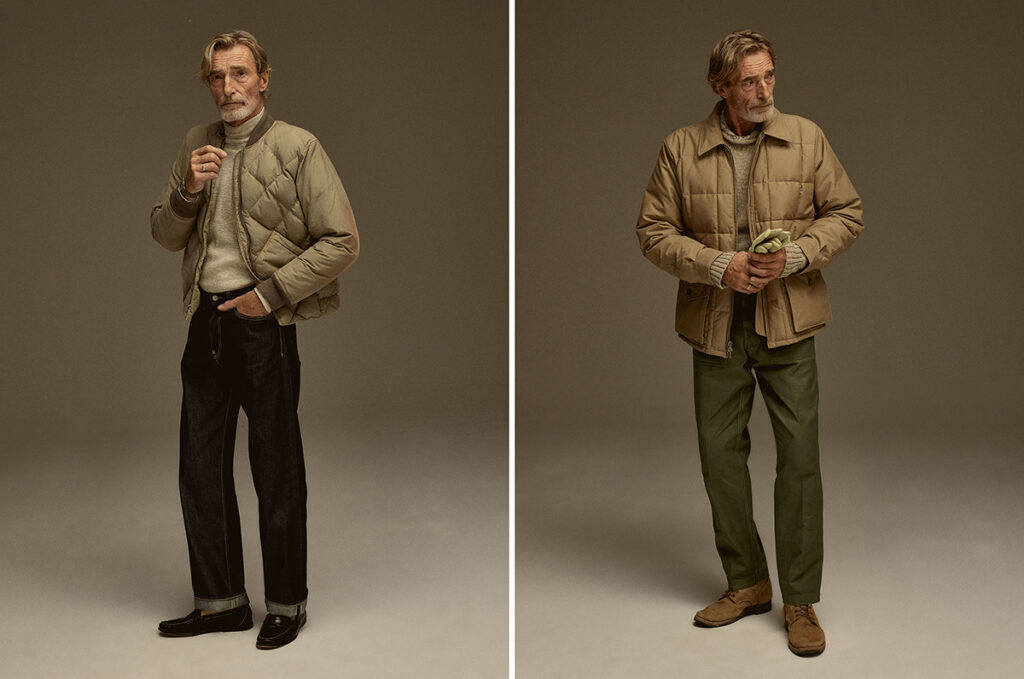

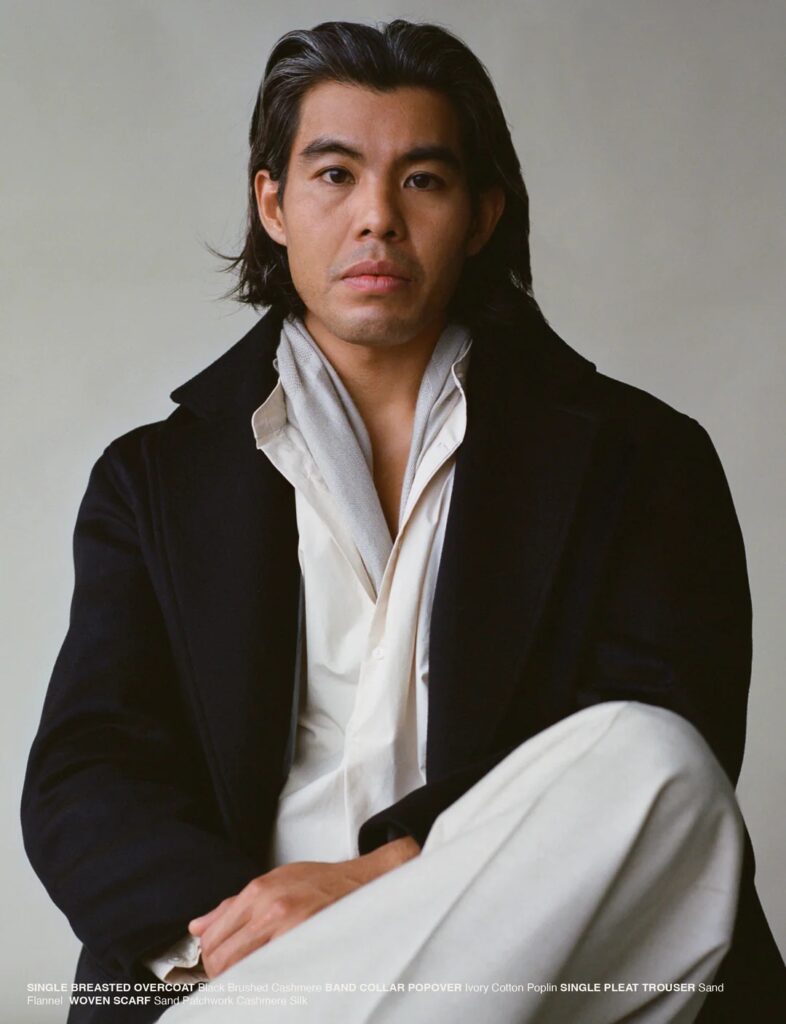

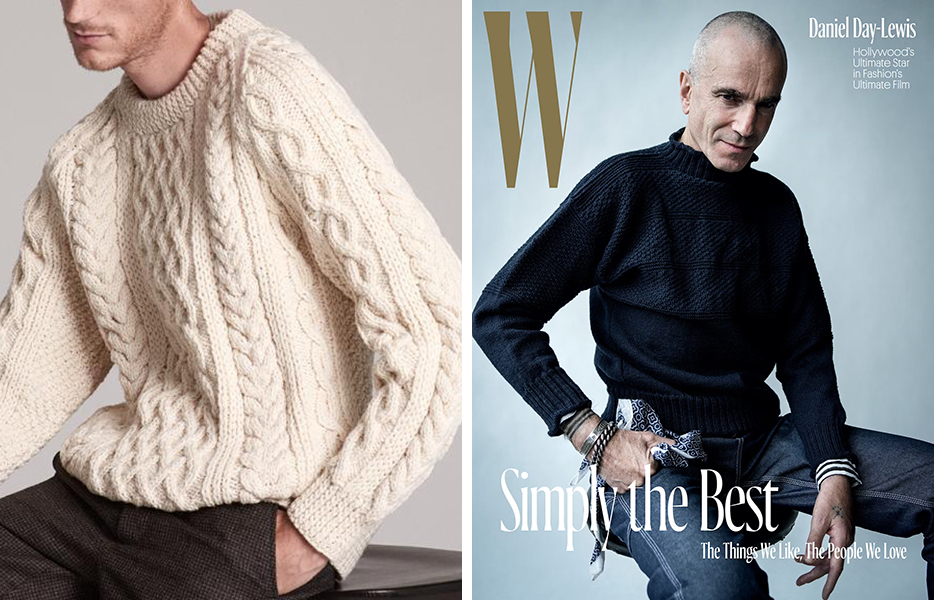

Speaking of fisherman knits, I’m excited to dust off my Arans and Guernseys, two styles historically associated with fishermen around the North Sea. If lore is to be believed, these sweaters used to carry patterns distinctive to specific families, making them something like heraldic crests. Supposedly, when the poor, dead bodies of drowned fishermen washed ashore, families could identify their loved ones by their knitwear. As far as I can tell, there are no firsthand accounts of anyone’s body being identified this way. I’ve long suspected this story is drawn from a moving passage in John Millington Synge’s 1904 play Riders to the Sea, in which a woman identifies her dead brother by his stockings. In any case, the story hints at a kind of bittersweet nostalgia, which is why I imagine the knitwear industry perpetuates it. I like Arans in “tidier” outfits, such as Sid Mashburn’s five-pocket cords worn with quilted jackets (this season’s Buck Mason x Eddie Bauer collab has some incredible options) and then dropped-shouldered guernsey with vintage Lee truckers or Schott double riders. If you can afford one, Flamborough Marine makes beautifully hand-knit, bespoke guernseys, including the one Daniel Day-Lewis famously wore on the cover of W Magazine. Rajiv Surendra looks pretty great in his, too. (Side note: I’ve been enjoying Surendra’s YouTube channel, which feels like a throwback to 2007-era Internet—earnest, fun, and aesthetic-driven).

Options: Bosie, Harley, O’Connell’s, The Andover Shop, J. Press, Drake’s, Laurence J. Smith, Spier & Mackay, The Carrier Company, The Armoury, Trunk Clothiers, William Crabtree, Junior’s, Monitaly, Inis Meain, De Bonne Facture, Fujito, Aran Sweater Market, Ó’Máille, Inverallan, Flamborough Marine, Wallace & Barnes, Ralph Lauren (I’m still a sucker for this sort of stuff), LL Bean, Peregrine, Colhay’s, J. Crew, The English Difference, Old H & Daughter, Bryceland’s, Mr. P, Officine Générale, Howlin, RRL, and Kapital

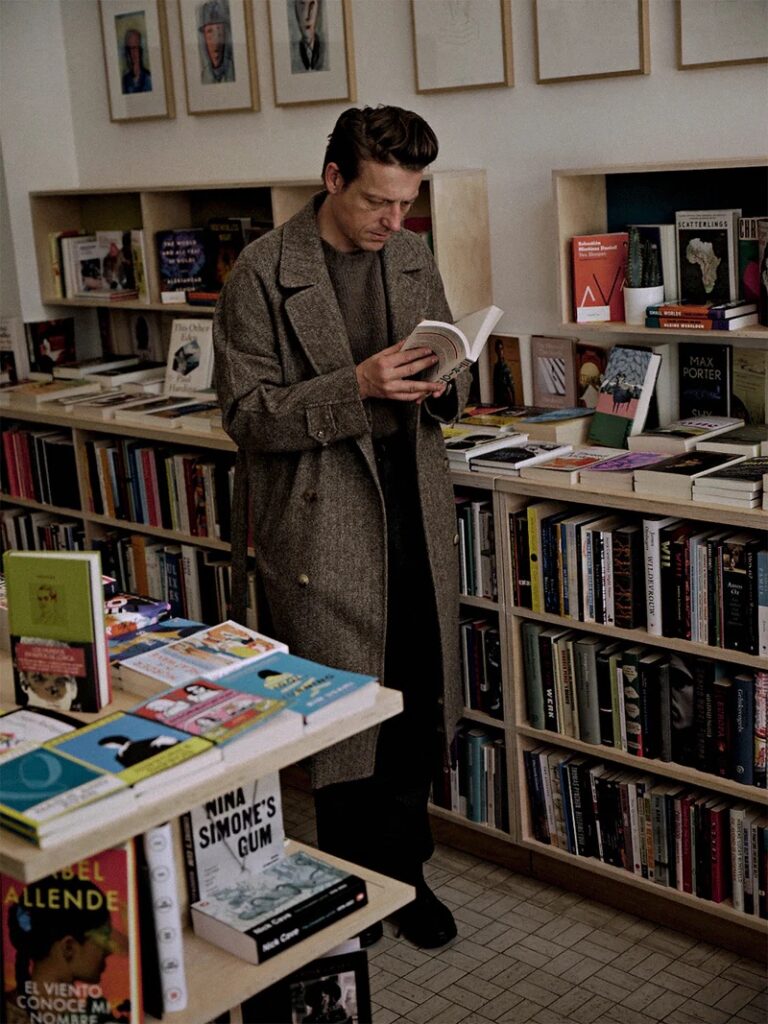

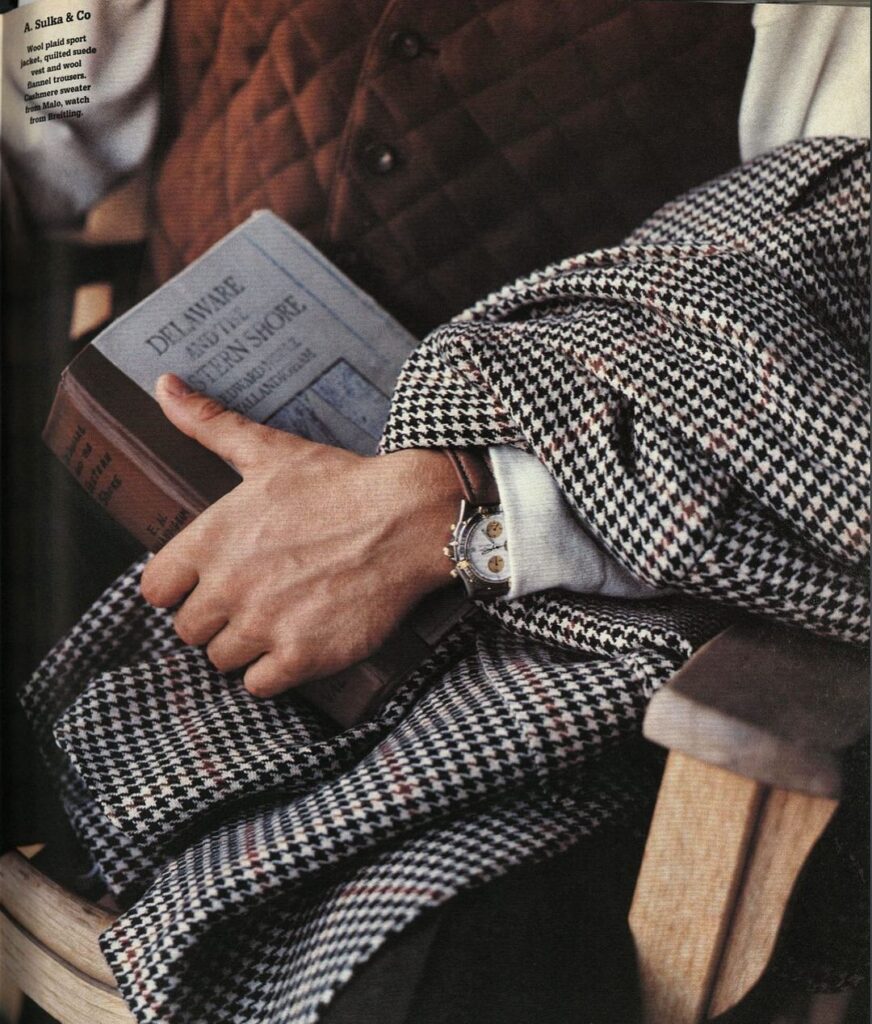

TWEEDS

Before the advent of modern loom technologies, European fabrics were stiff and heavy. City fabrics, such as those worn in London, were naturally more refined than country cloths, but they were still more substantial than the Super 100s you’ll find in stores today. Scottish fabrics were rougher still. After the union of the two kingdoms, an economic board was set up to organize the cottage industries around Scotland. Among those were tweed weavers, who, for centuries, made fabrics designed for rugged use out in the countryside.

In the old days, Scottish tweeds were woven from local and native wools, and often Cheviots spun into woolen yarns. As technologies improved and international trade increased, Britain started importing German textiles, which were softer and more refined. In old, mid-19th-century clothing catalogs, you’ll find clothes described as being made from “German Lamb” and “German Fleece,” which is to say they were constructed from superfine Silesian and Saxony merinos (what today would be called English “Botanies”). And yet, even against the possibility of this superior comfort, Scottish tweeds persisted for the same reasons they do today.

Tweed somehow manages to be one of the least and most comfortable materials you can wear. It’s the “least comfortable” in the sense that it’s often too prickly to be worn against bare skin, which is why it feels and looks better when layered over thicker dress shirts—oxford cloth button-downs, brushed cotton flannels, or snap-button denim Western shirts. Tweed trousers, if you have occasion to wear them, often need to be fully lined. At the same time, tweed has an undeniably comforting quality. It’s hardy and reliable, sturdy and flattering. It makes you feel braced for the world, presentable but shielded. In a classic cut, a tweed jacket is something you can wear for the rest of your life (I still have my father’s tweed from the 1980s).

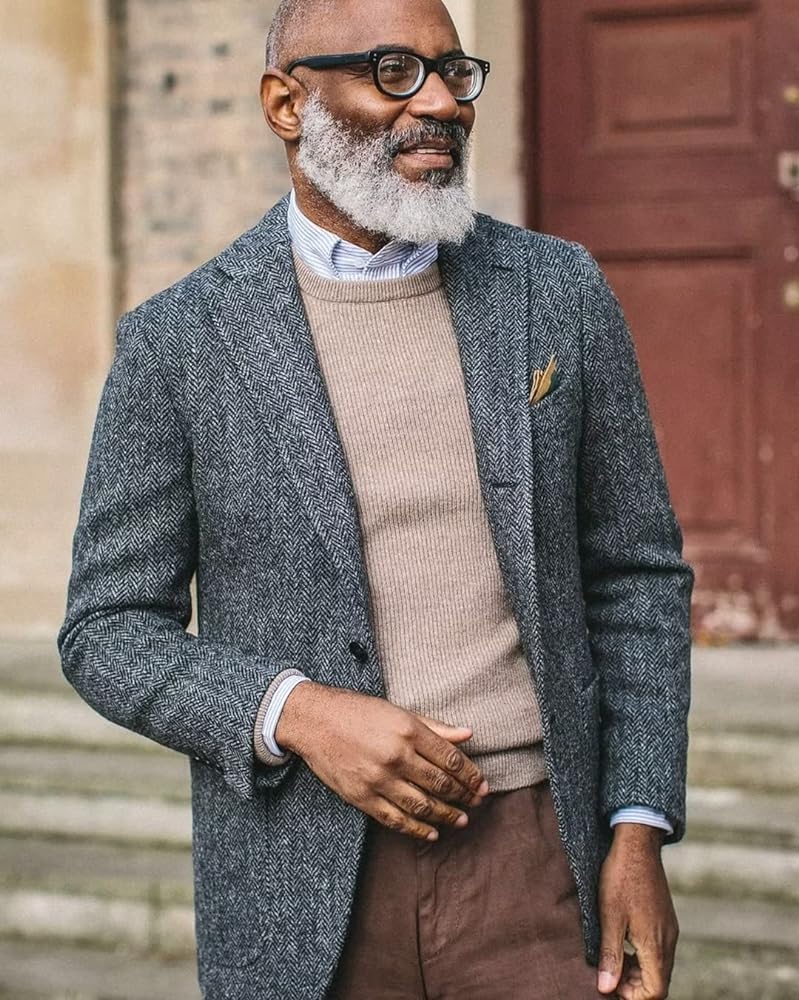

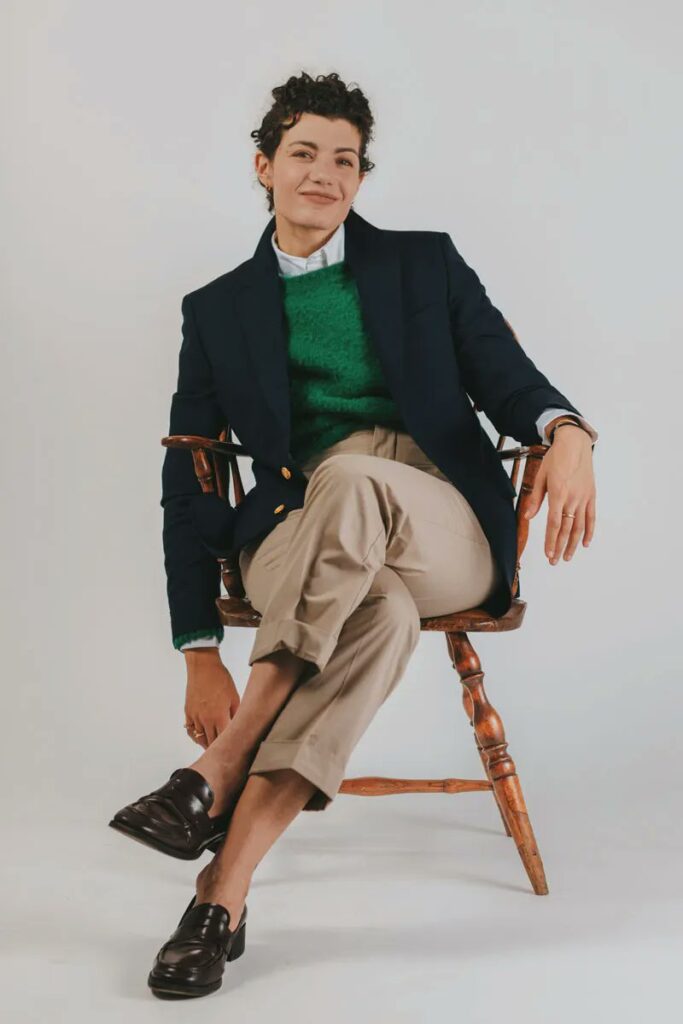

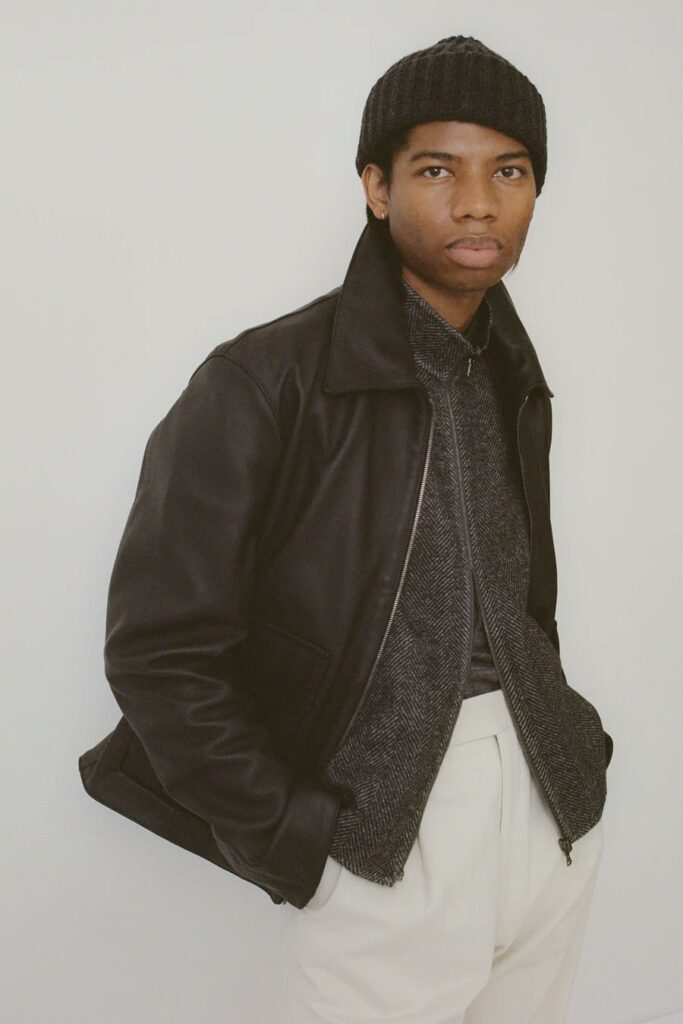

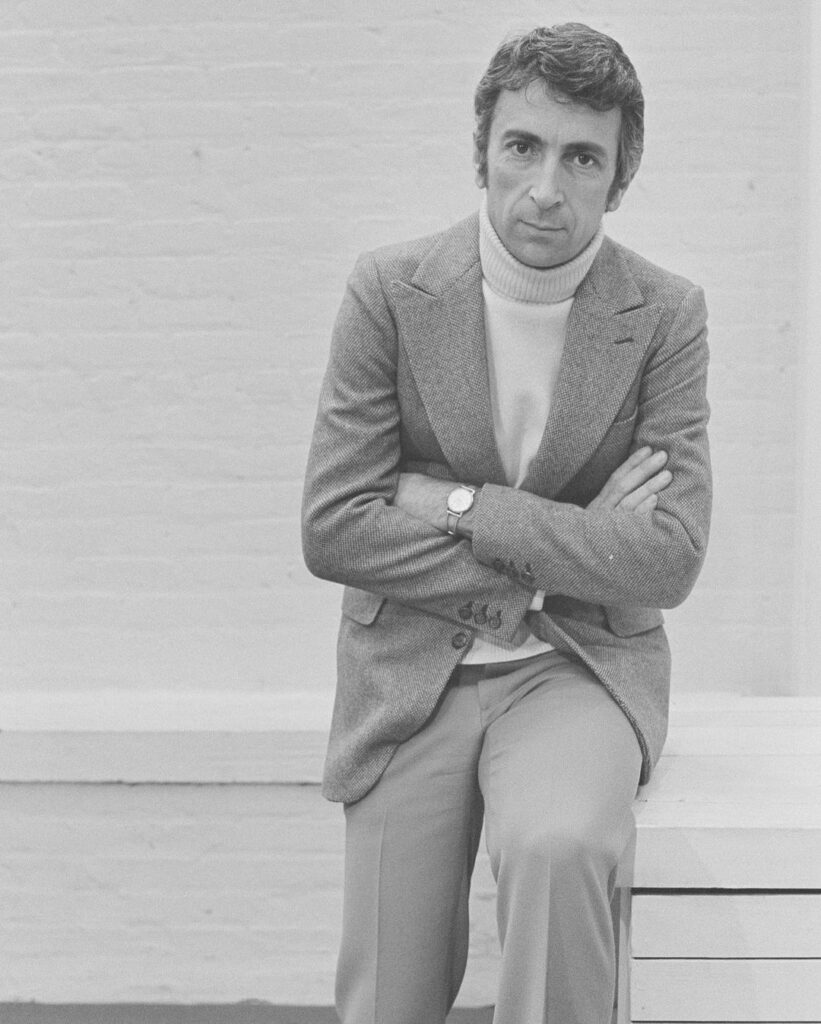

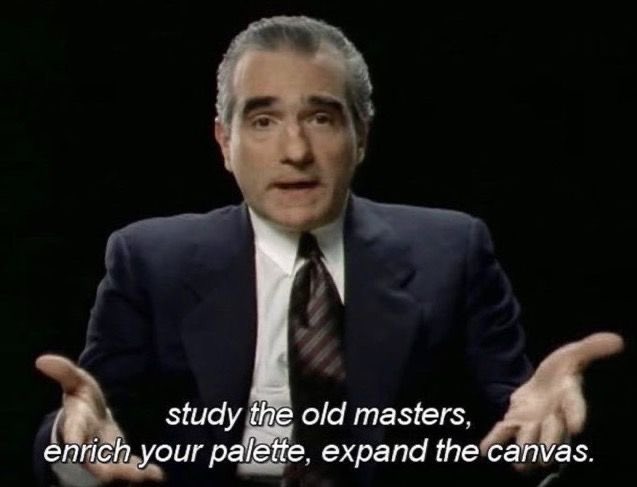

I’m excited to break out my tweeds again this fall. There’s a dark brown Donegal that I consider to be my most versatile, as it adds visual interest to plainer outfits without clashing with patterns. Next is a mid-brown glen check inspired by something Gianni Agnelli once wore. In my mind, these are the first two tweeds anyone should buy—something in mid-brown and another in dark brown—which you can pair with grey flannel trousers, taupe whipcords, tan chinos, blue denim, and five-pocket cords in earthy colors such as olive. Once you have at least two brown tweeds (the hue and shade matter more than the pattern), it’s worth branching out. Blue tweeds can be your winter counterpart to navy blazers, while grey tweeds look particularly sophisticated at night. If you’re looking for an evening outfit, consider wearing a grey tweed with contrasting grey twill trousers, a white shirt, and a black knit tie. It can also be teamed in the daytime with brown five-pocket cords, tan chinos, or light-washed jeans (for that Robert Redford look). Tweed sport coats look especially good when dressed down with a thin merino turtleneck or a snap-button denim Western shirt (a classic Ralph Lauren move).

Options: J. Press (this season’s fabric selection is incredible), The Andover Shop, O’Connell’s, Sartoria Carrara (they have a very appealing grey-brown glen check), The Armoury (this looks very tasteful), Spier & Mackay, Besnard (they have a dark brown Donegal), Bryceland’s (a nice grey Donegal) The Anthology (a grey herringbone and brown houndstooth tweed), Berg & Berg (very nice mid-brown glen check with a good pattern scale), Natalino, and Cavour (they also have a nice mid-brown glen check)

CAVALRY TWILL SUIT

When much of our economy shifted to work-from-home arrangements in 2020, I worried whether this would spell the end of tailoring, a final death blow to an industry beleaguered by decades of business casual. After all, what could be more casual than working from home with no one to see except for the occasional Zoom meeting? But in the last few years, I’ve found myself wearing tailoring more, not less, and even reaching for the casual suits that have long sat in my closet with good intentions but minimal wear. The problem with casual suits is simple: they are too casual for settings that call for a suit but too formal for situations that don’t. A sport coat teamed with odd trousers will always look more natural in most semi-casual environments. But I’ve come around to thinking that a suit looks better than a sport coat—its lines are sleeker and sharper, as the jacket seamlessly flows into the trousers—and after that frustrating year of being stuck at home, I want to enjoy wearing whatever I want to wear.

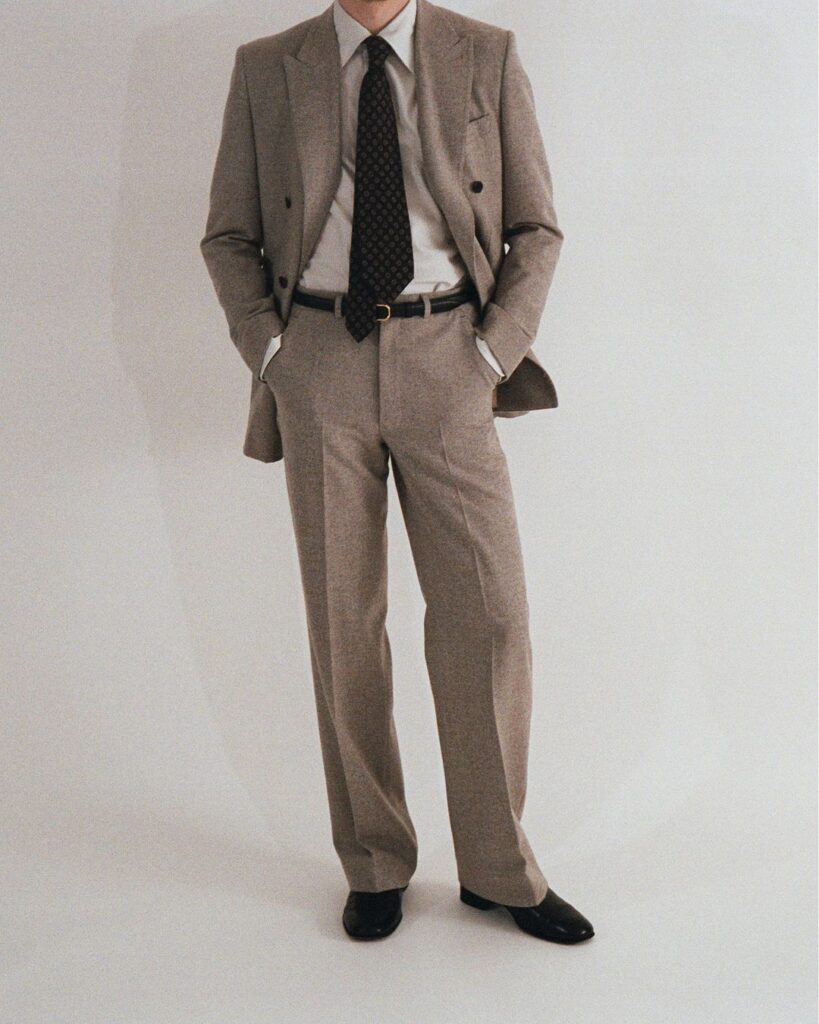

This fall, I’m excited to wear a newly acquired brown cavalry suit from I Sarti Italiani. The suit is inspired by something I saw on Buzz Tang, co-owner of The Anthology. It’s a double-breasted design (although mine is a 6×2 closure) with generously sized peak lapels and pleated trousers. I was initially skeptical of the cloth, as cavalry twill is typically used for trousers, and its sheen is more visible in darker colors. But I Sarti Italiani’s prices are uncommonly competitive for custom tailoring, and I dove in after receiving some encouragement from Bruce Boyer. I’m glad I did. When paired with a snap-button denim Western shirt and some black tassel loafers, this suit makes me feel like Hank Williams crooning on stage.

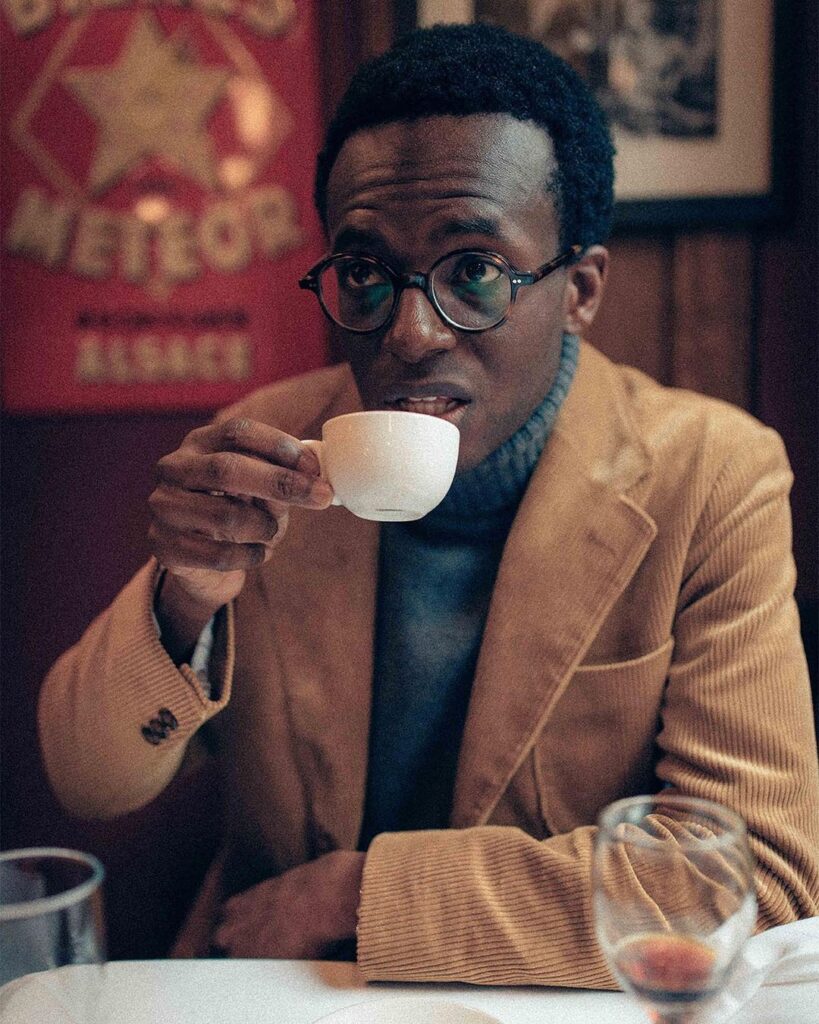

Most men nowadays could use at least one “serious suit” for weddings, funerals, and court appearances. Make that suit conservative—a single-breasted with notch lapels cut from a dark worsted cloth in a sober color such as navy or grey. But unless you have to wear suits for work, your second suit should be something fun. In the springtime, that can be rumpled linen or brushed cotton; for summer’s heat, choose seersucker (tonal navy, if you’re afraid of looking like Southern trad who swills mint julep at garden parties). For fall and winter, it can be ribbed corduroy, Thornproof tweed, or cavalry twill. If you get a more “basic” cloth, such as woolen flannel, consider making it a double-breasted glen check instead of a conservative single-breasted in a solid color.

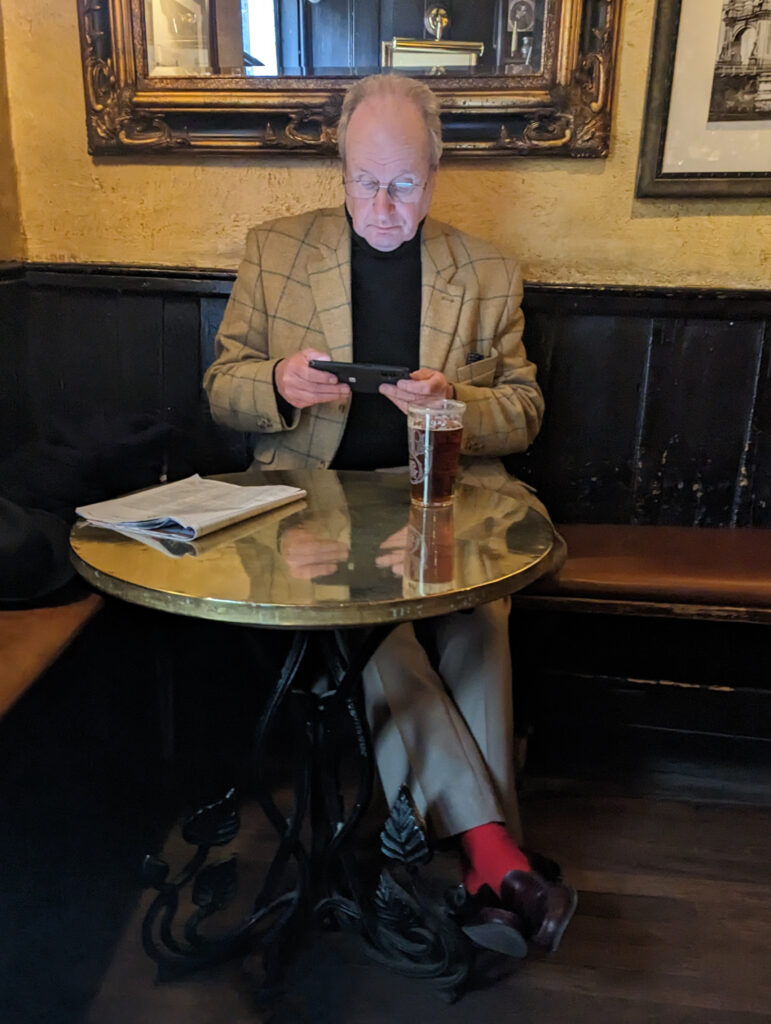

Nowadays, the lack of dress rules means you have greater freedom to wear whatever you want. You can wear casual suits anywhere from cafes to the theater, but if you’re looking for an excuse to get dressed up, I suggest going to a nice restaurant or bar. It doesn’t have to be a three-star Michelin-rated restaurant; in the Bay Area, I’m talking about places that serve $25 plates of spaghetti. Even if no one else in the restaurant is wearing tailored clothing, the presence of white tablecloth will make a tailored jacket feel less conspicuous. I recently wrote something about this for Mr. Porter.

Options: Sartoria Carrara, The Armoury, Spier & Mackay, J. Press, The Andover Shop, O’Connell’s, The Anthology, Berg & Berg, Anglo Italian, Natalino, Cavour, and Suitsupply

STOUT HOODIES

Call it the Fetterman Effect, the most recent political dress controversy over which I’ve been spared no grief. But over the last year, I’ve been really into hoodies.

The hoodie today is electrically charged with meaning, but when Champion debuted the first ones in the 1930s, they were primarily worn by gruff New Yorkers operating forklifts inside frigid warehouses, as well as footballers trying to stay warm on the sidelines. The hoodie during this period was uncontroversial—indeed, it enjoyed a brief halo effect from its appearance in the film Rocky. But by the close of the century, the hoodie became embroiled in every cultural and political war of its day. In the United States, it has become wrapped in respectability politics and debates about Black youths; in Britain, it has come to represent “all that’s wrong about youth culture,” according to David Cameron. The irony of the hoodie is that people such as Mark Zuckerberg have turned it into a New Economy status symbol—a defiant stance for meritocracy and against the traditional suit-wearing industries of the East. But when worn by Black youths and skateboarding white teens, the fleece hoodie causes a moral panic. The hood shields not the face of a person who is cold or wants to be left alone but a criminal who’s trying to avoid detection. In some ways, the hoodie answers the age-old style question about whether clothes make the man. In reality, we judge clothes by the bodies underneath them.

Throughout these decades of controversy, supporters of hoodies have pointed out an indisputable fact: these fleece sweats are supremely comfortable, which is why many people wear them. They function like a comfort blanket at home (a slightly more respectable version of the Snuggie) and work nicely with jeans when running errands in the neighborhood. I prefer the stout cotton versions that remind me of the classics, such as the ones Russell Athletic produced in the 1980s and ’90s. Vintage Russell hoodies have a short, boxy fit and slightly dropped shoulder seam—a silhouette that has been endlessly copied in recent years.

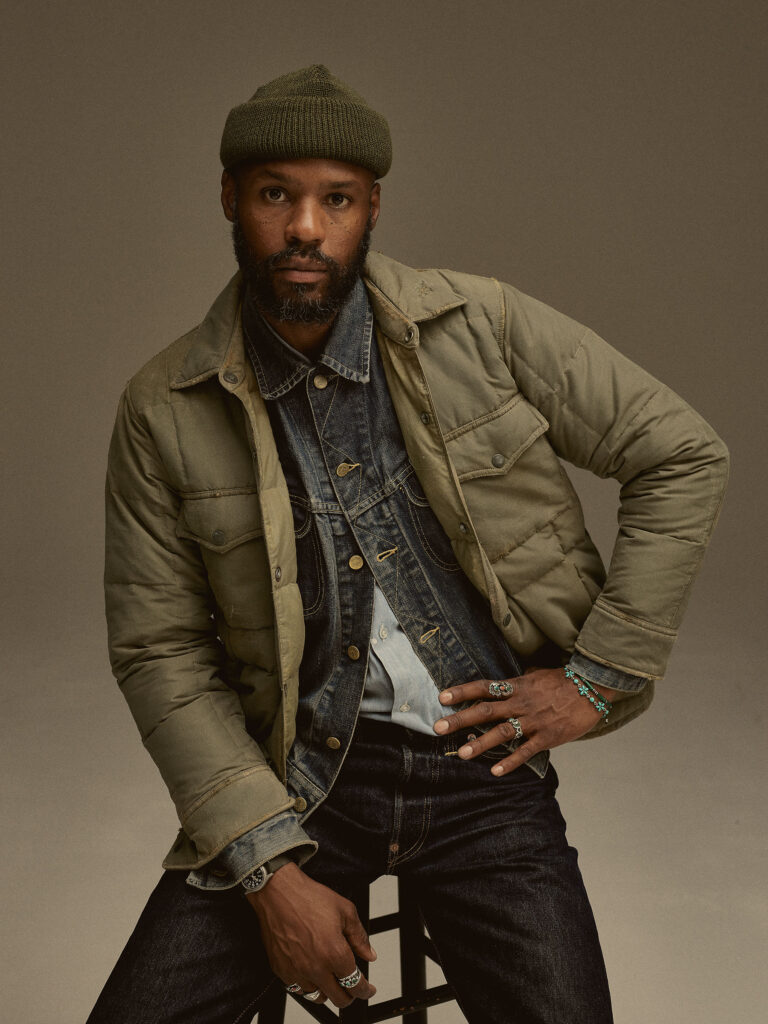

There are a few notable models. Camber is the label-under-the-label, historically producing for Bape offshoot Very Ape and Engineered Garment’s Workaday. Their Philadelphia-made knits are so dense that they effectively function as fleece shields. But their fit can be ginormous, which is either a good or bad thing, depending on your religion. If you want a slightly updated design, American Trench recently debuted “Original Equipment,” a new sub-label that features Camber-made hoodies in a trimmer fit (I recommend going one size up). Their sweatshirts, like Brut’s (pictured above), have hoods that neatly sit on the shoulder, framing the wearer’s face. I think this looks better, but the hood takes some adjusting when you first put it on. Alternatively, there are slouchier hoodies—such as Frizmworks, Lady White, and Les Tien—which have larger hoods that drape across your back. I find those to be a little more comfortable, but they lack the frace-framing effect of the others. I’ve been eyeing this Re/Done hoodie, which is made to look like the sun-faded originals coveted by vintage collectors (those go for hundreds of dollars on eBay).

Options: Brut, Original Equipment, Kaptain Sunshine, Unfil, Camber, Frizmworks, Lady White, Re/Done, Les Tien, Visvim, Carhartt WIP, J. Crew, Los Angeles Apparel, Todd Snyder x Champion, Warehouse, Madewell (now designed by Aaron Levine), Reigning Champ, Wolf vs. Goat, Engineered Garments, and vintage Russell Athletic. While not a hoodie, Carter Young’s quarter-zip fleece also looks nice and would serve a similar effect.

FLANNEL SHIRTS

A few years ago, I wrote a style profile about Andrew Chen, co-founder of one of my favorite denim brands, 3sixteen. I’ve always thought that Chen’s style can be a good source of inspiration for guys who want to dress better but don’t see three-piece suits and avant-garde leather jackets in their future. Like many men I know, Chen grew up with an avid interest in music and street culture, and today is a busy father to two young boys. He prefers comfortable and easily washable clothes, ideally made from materials that age well with time. “I don’t think my wardrobe has changed much over the years,” he told me. “It’s strange when someone asks to do a profile on how you dress because I never really thought about it before. But the other day, I looked at my closet, and it was full of plaid flannel shirts. I still wear the same things I wore fifteen years ago—hoodies, sweats, flannels, t-shirts, and jeans. Things just fit better.”

For as long as I’ve known Chen, he’s never been dogmatic about style, so it was like pulling teeth to get him to give me some tips on how people could shop for better flannel shirts. In the end, the most he would give me is his preferences, encouraging me to tell my readers that they also have to find theirs. “When I shop for a flannel, I pay attention to the material. Flat Head’s flannels are unique because their yarns are so coarse and thick that the weave looks three-dimensional. I also love Iron Heart’s flannels because of their sheer weight. Living in a city with colder winters, they’re comfortable and useful.”

I’ve also found that to be true of flannels. The thin, limp ones I bought from Uniqlo years ago never ended up getting that much wear. I ended up donating them, hoping that they land in someone’s home rather than a landfill. But the ones that ended up costing me a little more—such as those from RRL, Wallace & Barnes (the heavyweight ones back in the day were especially good), Taylor Stitch (another great value), and Iron Heart (laughably expensive, but incomparable in weight and build)—have become staples in my wardrobe. They’re comforting and familiar, like old tweed jackets, and feel even better with a spritz of a fragrance (on flannel shirts, I like Tauer’s Lonestar Memories, Diptyque’s Tam Dao, Timothy Han’s On the Road, Atelier Perfume’s Vanilla Smoke, and Kerosene’s Follow). For some additional warmth and visual interest, layer one of Todd Snyder’s waffle-knit henleys. The open placket looks great underneath the flannel when the top two buttons are undone.

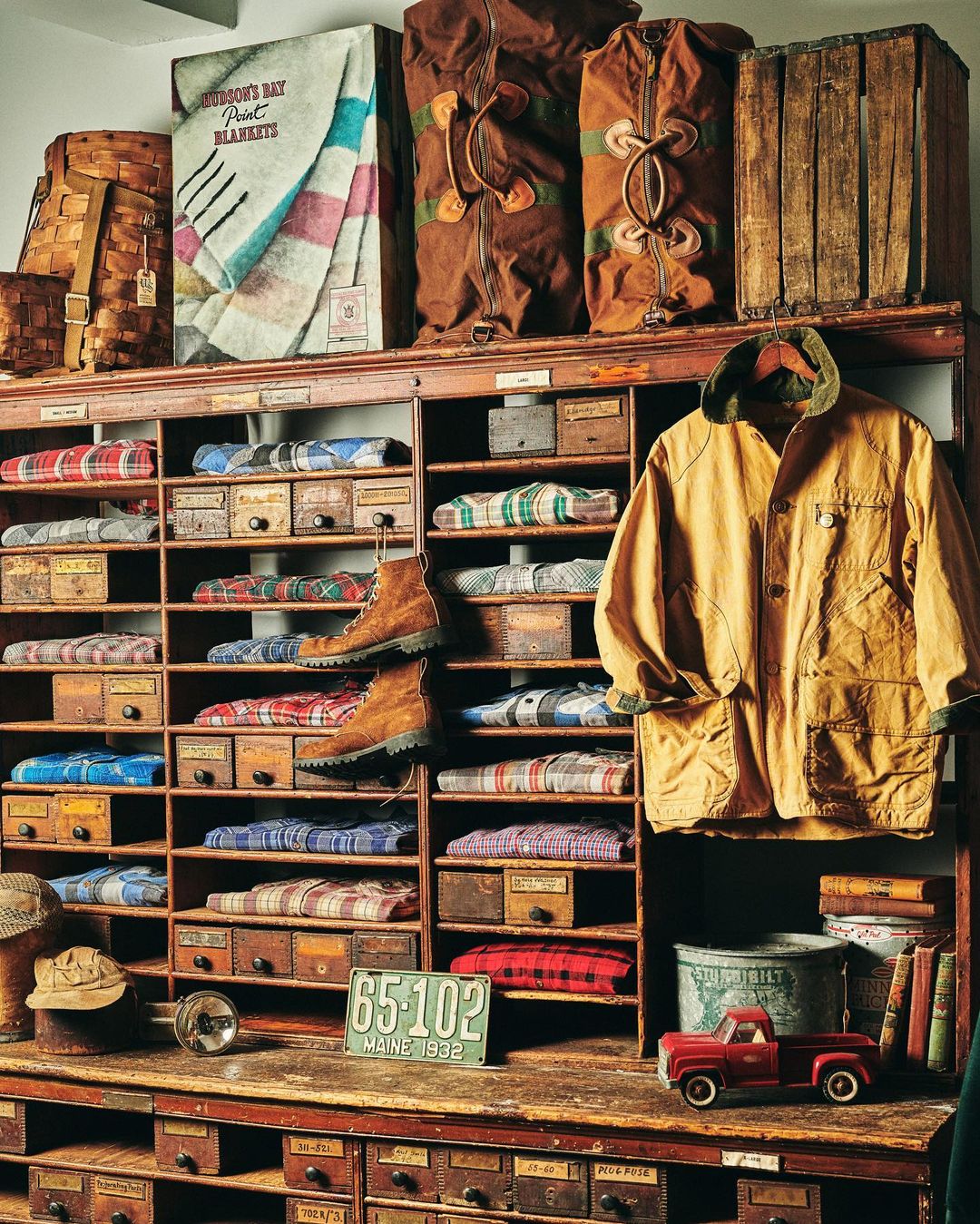

Options: 3sixteen, RRL, Taylor Stitch, Portuguese Flannel, Wythe (this one looks great), J. Crew, Alex Mill, Todd Snyder, LL Bean, Vermont Flannel, Faherty, Flat Head, Iron Heart (size up), The Real McCoys, Imogene + Willie, Beams Plus, Filson, Pendleton, American Giant, Spier & Mackay, and Proper Cloth (good for dressier MTM flannels you can wear with sport coats). Lastly, don’t forget vintage. You can search eBay for brands such as Big Mac, Five Brothers, and Big Yank, or hit up vintage shops such as Broadway & Sons, Wooden Sleepers, Velour, and Raggedy Threads.

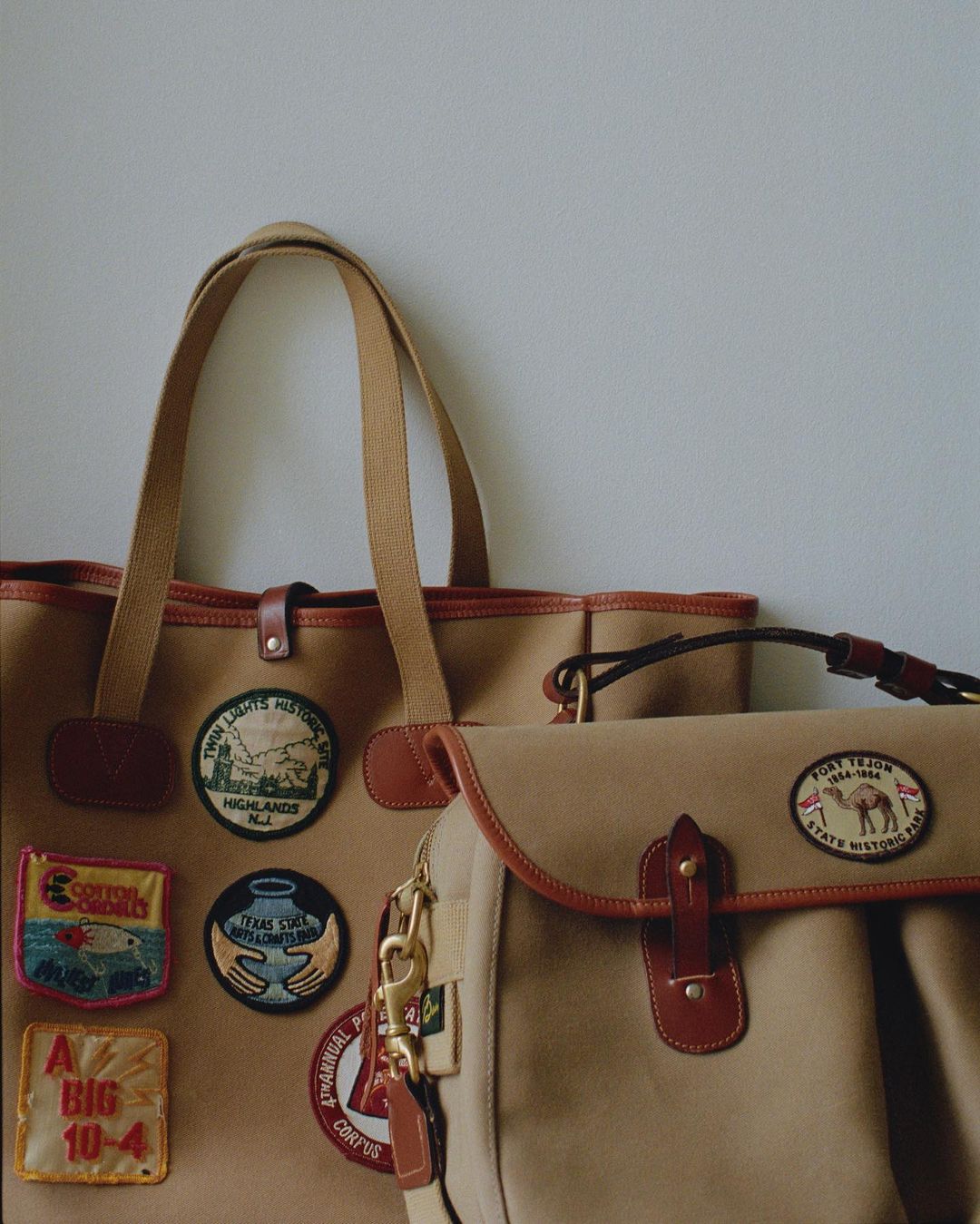

PATCHES ON BAGS

I’ve been collecting vintage patches for years, picking them up here and there whenever I visit a flea market or vintage shop. Over the summer, I finally found time to sew them onto a canvas bag. The style is a bit camp—literally and figuratively—but I’ve enjoyed how it’s a nice, easy way to update something in a wardrobe without spending too much money. “Patched up” bags go nicely with anything that can be described as workwear, Ivy, or Americana. The only caveat is that I think the style works better on a heavier canvas—such as the Brady bags pictured above (available at Beige), a Wooden Sleepers tote, an LL Bean’s tote, or a Kapital Snufkin—rather than the thin, flimsy totes you get for free at some shops. If you can’t be bothered to hunt down patches and sew them on yourself, I’m sure Jared DeSimino has something ready-made for you.

Options: Scour your local flea markets and vintage shops for patches. If you’re shopping online, you can find hunting, camping, and political-themed patches on eBay and Etsy (I personally like camping ones best). North No Name and Fort Lonesome also have some nice vintage-inspired styles.

HUNTING BOOTS

LL Bean’s Maine hunting boots—affectionately known as the Bean Boot—were a darling of the online menswear community in 2010, when men posted photos of Gianni Agnelli and 1960s America to justify the supposed timelessness of their skin-tight clothing. After the flood of jpegs of men wearing Bean boots with stacked brackets and ties askew, they became another causality of that era, along with Blackwatch tartan, Filson briefcases, and, unforgettably, double monk shoes.

To be honest, mine never left my regular footwear rotation, although I found a better place for them in my workwear wardrobe. Their original function as a hunting boot makes them a natural companion to Ralph Lauren’s 3-in-1 parka, Barbour x To Ki To outerwear, and vintage Saf-T-Bak hunting coats. I’ve come to appreciate that they’re the perfect rainboot—considerably more practical than my Le Chameau Wellingtons, whose calf-high lengths always feel like overkill in California rain, and they’re more affordable, too. Bean boots are charmingly ugly and functionally waterproof. A pro tip: leave these on your back porch during the summer so the sun can beat the leather uppers into a pleasing pale blonde hue. That will make them look like the old, weathered Bean boots occupying many Americana mood boards.

Speaking of hunting boots, I’m excited to break out these Russell Moccasins. Inspired by something that used to be in Ralph Lauren’s catalog in the 1990s, they’re a modified version of the company’s Birdshooter. Made from heavily grained WeatherTuff leather and cushy Airbob soles, they have a double-leather construction on the lower half of the boot to make them more weatherproof. Russell Moccasin works on the old mail-order catalog system for custom footwear, where you trace an outline of your foot and write, in pencil, the details of your order (very pre-internet). Nearly all of their shoes fit a half-size large, and I found this to be true for custom orders (they do free remakes if the first delivery doesn’t fit). I’ve never hunted for anything other than coupon codes, but friends tell me this is because actual hunters double up with thick socks. In any case, their chunky silhouette goes well with wider workwear pants, such as Carhartt double-knees and olive fatigues. The online catalog seems thin nowadays—although it still features the very handsome “fishing oxford.” Consider reaching out to them to see if they have paper catalogs that allow you to see the full breadth of their offerings.

Options: LL Bean (go down a full size, or 1.5 sizes down if you wear half sizes), Russell Moccasin, Yuketen Maine Guide and Angler, Gokey sporting chukka, Filson Uplander, Quoddy Telos, Oak Street Bootmakers, Rancourt, and Paraboot Beaulieu (Eisuke Yamashita’s pictured above)

COZY SOCKS FOR COLD TOES

If you, like me, get cold feet easily, you have to try Rototo’s double-face socks. They’re like little sweatshirts for your feet. Inspired by mountaineering socks, they’re thick and slubby, made from a heavily textured yarn, and feature terry loops on the interior. The only thing is that they’re too thick for boots, so I mostly wear them at home with Town View’s moccasins. Rototo also has thicker Nordic-styled socks with little rubber grips on the underside, so you can use them like house slippers.

If you’re looking for something you can wear with boots, I’ve been really enjoying American Trench and Thunders Love. American Trench’s Supermerino socks are made from an insulating woolen-spun yarn and feature a comfy, cushioned footbed. When I bought mine about three years ago, I was a little disappointed with how quickly the material started to felt after a few washes. Felting is when the wool fibers start to tangle and mat together, creating patches of fluff. I initially figured these socks would quickly wear thin. But three years later, they’ve held up remarkably well and haven’t lost any of their elasticity. They’re incredibly warm and comfortable, and feel like kittens hugging your feet. The company’s Donegal-styled wool-silk boot socks are a favorite, too.

Finally, Thunders Love is a Spanish hosiery company with impressive design skills. They often utilize uniquely colored or textured yarns or interesting knitting techniques to create socks that look fun without being overly whimsical. I’ve been really into their recycled wool socks, which feature a double-face design that results in a uniquely flecked appearance. The socks come in deep tones that are somehow sophisticated and fun at the same time and they’re just thick enough to comfortably fit into my Blundstone boots.

Options: Rototo, American Trench, and Thunders Love

Note: I’m now doing a podcast with my friend Peter Zottolo. The show is being produced through Blamo! and will be hosted behind Blamo’s Patreon wall. For five bucks a month, you get access to our show, the JJJ show, and Blamo Extras, as well as Blamo’s Slack channel. You can preview the first 21 mins of our first show here.