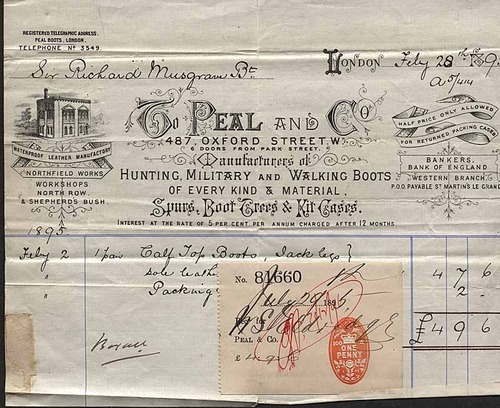

When it comes to menswear history, it can be challenging to separate fact from fiction. The two are often intertwined in vanity books and marketing pamphlets, and these stories persist because they help companies sell clothes. The best accounts are rooted in primary sources, such as newspaper articles, archival records, or oral histories from reliable voices. Housed within the four brick walls of the London Metropolitan Archives, a public research center specializing in the history of London, are the dusty archival order books once owned by Peal & Company.

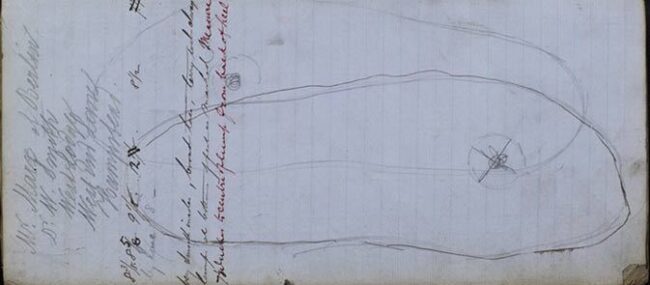

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Peal & Co. was the largest bespoke shoemaking operation in the world. Their salespeople traveled to various continents to take orders from kings, queens, captains of industry, authors and actors, poets and pioneers, and the otherwise well-heeled. Upon meeting each client, a Peal salesperson would crack open a large leather-bound ledger—charmingly known as a Feet Book to people within the company—and trace an outline of the client’s feet on the two blank pages. They would then write the person’s name and any necessary notes about the order.

While flipping through Peal’s Feet Books, you can see storied names from the 19th and 20th centuries: Henry Ford, Condé Nast, Anthony Eden, John F. Kennedy, Barry Goldwater, Charlie Chaplin, Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, and Gary Cooper, among the many. Since Peal’s sales associates typically recorded these names in full, there’s no doubt who ordered what. But buried on page 142 of one of the earliest books is a mysterious entry for “Mr. Marx of Berlin.” It’s estimated that this record was made sometime in the 1870s, which matches when Karl Marx lived in London. A notation on the order says the finished shoes should be delivered to Dr. W. Smith in the intellectual Hampstead area, where Marx was known to ride donkeys and picnic at the time.

It’s surprising that the scourge of the propertied class would have bought bespoke shoes from the same place that supplied members of the Rothschild and Rockefeller families. This is not just because of his politics but also his financial history. Marx settled in London in August 1849, shortly after publishing the Communist Manifesto and having been expelled, for the second time, from Paris. The Marx family arrived in England with nothing in their pockets, and dreariness trailed them like a black dog for the first fifteen years. In 1850, they were evicted from their home, and their possession seized. After they moved to a two-room hovel in Soho, they subsisted on bread and potatoes. Marx claims he hardly went out because he had to pawn his good clothes (even in 1850, drip was essential). Finances were so bad that when Marx’s son Guido, who suffered from violent convulsions, died at the tender age of one, his wife frantically scrambled to borrow money for a coffin.

Except for one occasion, Marx refused to seek gainful employment during this time, so he subsisted on the weekly subventions of his compatriot Frederick Engels. The sums were modest at first, as Engels began as a clerk at his father’s cotton spinning mill. But they grew generously once Engels graduated to partner. By the mid-1860s, Marx’s financial position improved. His wife received two small inheritances, and he wrote for various publications, published Das Kapital (1867), and invested some money in the London Stock Exchange. In 1864, he wrote a letter to his uncle Lion Philips: “I have, which will surprise you not a little, been speculating […] in English stocks, which are springing up like mushrooms this year. […] In this way, I have made over £400. […] It’s a type of operation that makes demands on one’s time, [but] it’s worthwhile running some risk in order to relieve the enemy of his money.” Apparently, he was also relieving the enemy of Peal’s better shoe leathers.

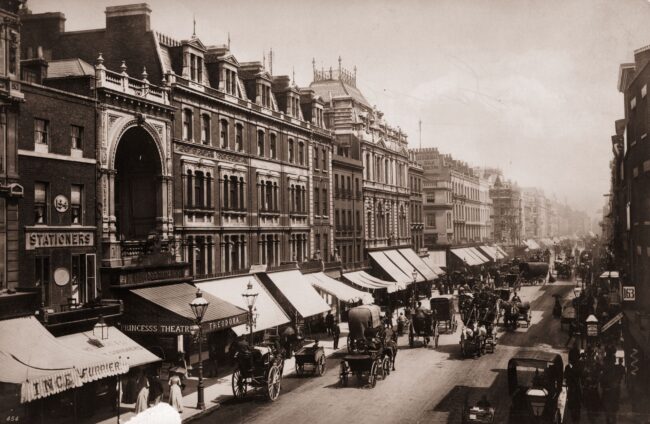

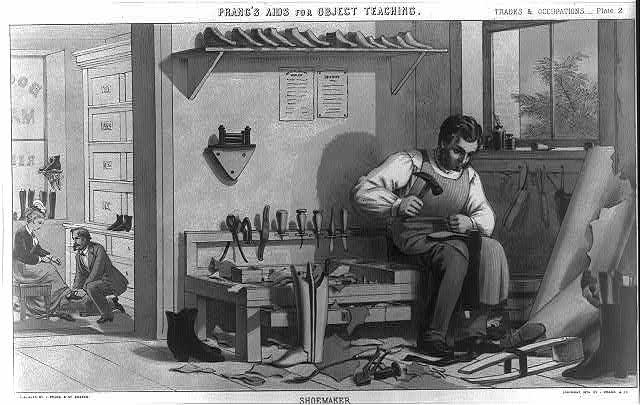

Although it’s surprising that Marx went to Peal, who was among the most luxurious of bespoke shoemakers, it’s not particularly remarkable that he had custom shoes made. In the 1870s, ready-made tailoring and footwear were still in their nascent stages, having been introduced just a few decades earlier (across the pond, Brooks Brothers debuted the first ready-made suit in 1849). The quality of these items still paled compared to what would have come out of a tailor or shoemaker’s shop. As such, many men during this period still had clothes made by a tailor, if they could afford one, or they had things made in the home. The same is true of their footwear. In the 1870s, London was teeming with shoemakers, who shod everyone from day laborers to kings.

Henry Mayhew, an English journalist and the co-founder of the satirical magazine Punch, gives us a clearer picture of London’s mid-19th century shoe trade. In his groundbreaking book, London Labour and the London Poor (1851), which drew from his Morning Chronicle articles, Mayhew documented the conditions of the ordinary workers who toiled behind the facade of Victorian metropolitan propriety. Using census data and Post Office Directory records, he estimates that 1840s London had 168,701 domestic servants and 50,279 general laborers employed in various trades. He also estimates there were an astonishing 28,574 boot and shoemakers, making it the third most popular occupation of all. About 2,000 of these workers were described as master bootmakers, a title we can assume meant they were cordwainers working in the prestigious West End.

We should put a note here about guild distinctions. In 19th century London, men in high positions—such as members of Parliament, judges and barristers, city bankers and stockbrokers, and well-heeled rakes—went to tailors and cordwainers to have their wardrobes made. Cordwainers crafted new shoes from new leathers using a client’s measurements. Those sitting a few rungs lower on the social and professional ladder—such as clerks, administrators, laborers, rapscallions and ruffians, costermongers and mudlarks, and the general ne’er do wells—went to cobblers. Cobblers repaired shoes or cobbled together new ones using scraps cut from old footwear. In the historic London guild system, these trades were so kept apart that, by the mayor’s order in 1395, cobblers were restricted from working with new leather, and cordwainers were similarly forbidden from meddling with old footwear. That’s why bespoke shoemakers today take umbrage at being called cobblers, a historically less respected position.

However, whether they were cobblers or cordwainers, every London tradesperson came from the working class. Contrasting with the facade of elite propriety projected nowadays through menswear blogs and YouTube channels focused on the bespoke arts, 19th century craftspeople were known for being drunk and unruly. In his book Nothing but the Best (1959), Thomas Girtin writes of the skilled tailors on Savile Row, including those occupying distinguished firms such as Huntsman: “They were all enormous drinkers. When they had been paid, they would ‘go on the cod,’ indulging in monster drinking bouts—drinking like a fish, perhaps—from which there was no recalling them until they had spent all their money.” While toiling away in workrooms, many of these hungover tailors sung derisive songs about their picky, privileged customers: “the words that gave them a most terrible shock / Were ‘I ordered a lounge and you’ve made me a frock.’ / Fol-de-rol-liddle-lol; the theme of my song / No matter what happens, the journeyman is wrong!”

Since these craftspeople were working class, it’s no surprise that many had radical views regarding class and governance. Thomas Hardy was a shoemaker and founding member of the London Corresponding Society (1792), a federation of debate clubs following the French revolution that agitated for democratic reform in the British Parliament. Hardy was such a thorn in the Crown’s side that he was eventually tried and convicted of high treason, after which he was sent to prison, where he died. Thomas Preston, a shoemaker who advocated for common ownership of land and democratic equality between the sexes, was one of the main organizers of the Spa Fields Riots (1816). Motivated by the misery and unemployment following the Napoleonic Wars, Preston and his co-conspirators designed an unconvincing scheme that was supposed to end with them taking control of the government (they, too, were tried for high treason). Perhaps the most notable of these attempted revolutions is the Cato Street Conspiracy (1820), where a band of Englishmen, most of whom were boot and shoemakers, plotted to murder the Prime Minister and the entire British cabinet. That ended with five conspirators at the gallows, and another five deported to Australia.

Marx commissioned his bespoke shoes sometime in the 1870s, during the last decade of his life. By this time, the Industrial Revolution had already begun in earnest. London was covered in a sooty fog, and the Thames River ran thick with sewage. Regent Park still had sheep grazing on its fields, and you could tell how long the sheep had been out there because their white fleeces would turn black in a matter of days. During these years, the sun was setting on the British bespoke shoe trade. This was the last hurrah before the big switch to ready-made production and the eventual importation of cheaply glued footwear. The trade would again never reach these heights.

“For me, the Golden Age of British bespoke shoemaking is sometime between the late 1800s and 1930s,” says Daniel Wegan, winner of the 2019 World Championships in Shoemaking. Born in Sweden, the shy Wegan found confidence through clothing and eventually moved to Northampton to learn how to make shoes. He ultimately landed a position in Gaziano & Girling’s bespoke department, where he worked for ten years before leaving in 2020 to start his independent bespoke firm, Catella. “In the late 1800s, there were so many shoemakers in Britain, and many of them had great pride in their craft,” Wegan continues. “There were also shoemaking competitions, which kept standards quite high. I think that standard lasted until about the 1940s or so, and things started to decline after the war.”

“Really? Things declined after the war?” I asked Wegan. That surprised me since, by almost all accounts, the Golden Age of classic men’s dress spanned sometime between the 1930s and ‘80s, and one only assumes that the bespoke crafts were still reliable during this period. After all, this was the era of debonaire actors such as Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, and Fred Astaire, whose enduring style was crafted in the backrooms of Mayfair. Wegan says the West End shoes he’s seen from the 1960s through the 80s were well-made but not particularly remarkable and that almost all the press during this period focused on celebrity clients and exclusive experiences.

I thought about the literature I’ve read covering the mid-20th century bespoke trade. Much of it came from major newspapers and magazines, written by eloquent sojourners who were passionate about their subject but perhaps needed to be more knowledgeable regarding the technical points of these crafts. Peter Mayele’s 1992 bestseller Acquired Taste, for example, is a collection of the articles he’s written for GQ and Esquire, each piece covering the indulgences of elites—millionaire mushrooms, breakfast champagnes, and shiny black caviar pearls. However, the most extravagant luxury is covered in his book’s first chapter, “A Gentleman’s Fetish,” which is about the guilty pleasures of buying bespoke footwear.

Mayle’s chapter opens: “To some men—even those who revel in bespoke suits with cuff buttonholes that really undo, or made-to-measure shirts with single-needle stitching and the snug caress of a hand-turned collar—even to some of these sartorial gourmets, the thought of walking around on feet cocooned in money somehow smacks of excess, more shameful than a passion for cashmere socks, and something they wouldn’t care to admit to their accountants.” So how did elites in the early 1990s justify spending $1,300 on shoes? (Or nearly $2,900 today, accounting for inflation.)

Mayle details the rarified experience, moving from the ritualistic process of being measured to choosing between an endless array of stylistic options—Cuban heels, sculpted waists, brass snaffles, seamless backs, and three-tone snakeskin punching. After waiting several months, a well-tailored purveyor presents the customer with what Mayle describes as “works of art.” “And the minute you put them on, your feet assume a totally different character,” he lauded. “They used to be frogs and have turned into princes. They have lost weight. Not only are the shoes lighter than ready-made shoes, but they are also narrower and more elegantly shaped. No wonder all those old boulevardiers spend hours staring downward, marveling at their aristocratic feet. You find yourself doing exactly the same.”

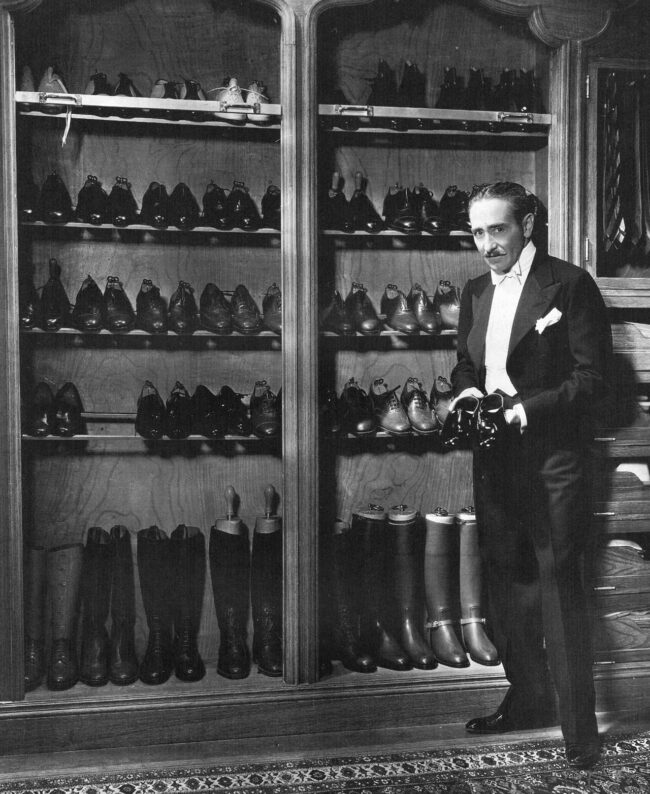

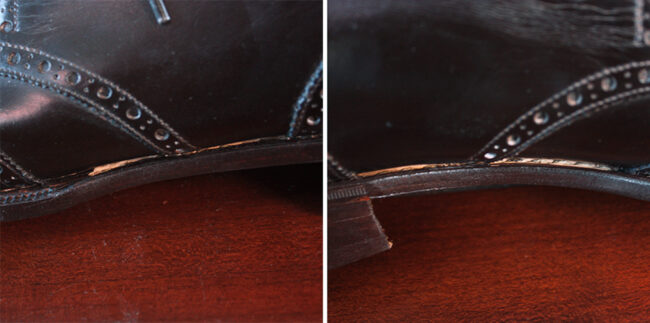

The vast majority of fashion writing, including those covering techniques such as bespoke, proceeds along these same lines. There’s an emphasis on the rarified experiences and elite customers, quietly suggesting that the reader can transform from a country commoner into a city gentleman if he follows these rules and buys those things. When you read pre-internet articles about bespoke footwear, there are spectacular stories about the indulgences of men such as Rudolph Valentino and the Duke of Windsor (the shoes in the second image directly above belong to the Duke). Likewise, Alexis von Rosenberg, Baron de Redé, was a prominent French banker, aristocrat, and collector of fine things. He owned hundreds of pairs of bespoke shoes, which were housed in a special room built with hidden closets that spanned from floor to ceiling along three walls. These racks held multiples of the same styles: four-eyelet black cap-toe oxfords, black imitation brogues for daywear, a signature tassel loafer of the Baron’s design, and countless opera pumps, as the Baron spent much of his life partying (these shoes are pictured in the first image directly above). As one of the main financiers of the Rolling Stones, the Baron would later introduce the band’s drummer, Charlie Watts, to GJ Cleverley, who remained a client of the West End firm until his death in 2021.

The main problem is that it takes more than the thickness of one’s wallet to be accepted into these socioeconomic classes—something everyone understands but dares not express. Yet, much of the lore of bespoke is built off these articles penned during the 1970s through the 90s, each piece doing little more than serving as Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous puffery. “I’ve never seen an article from that period where someone is breaking down the technical work that goes into a bespoke shoe, and why something made in the 1970s was necessarily better than what was produced in 1890,” Wegan adds. “Every article is about some Hollywood celebrity. But what do those celebrities know about shoemaking?” (At this point, I could hear Kanye’s voice saying, “I like some of the Cary Grant films; what the fuck does he know about bottom making?”)

“I think things are different now,” Wegan continues. “There are communities online where people can exchange information and learn about the finer points of shoemaking. If they receive a pair of bad shoes, they can tell other people online. If you bought a pair of bespoke shoes in the 1950s and they didn’t turn out very well, what recourse did you have? How would you even know if you received a lemon? For a more discerning customer, it’s not enough to talk about famous people anymore.”

The allure of working with one of the larger West End bespoke shoemaking companies burst for me some years ago after I commissioned a pair of bespoke shoes from GJ Cleverley, one of the two or three surviving heritage firms in this trade (depending on how you count). After four meetings and three fittings, the shoes I received had unusually marred soles and wrinkled uppers. The waist—the shoe’s middle—sagged so much that I could fit a business card between the sole and uppers. The shoes were also a size or two too large, and I could slide my index finger behind my heel when the shoes were worn. GJ Cleverley offered to remake the shoes, but when that went badly, we both agreed on a refund.

Since then, I’ve noticed other problems from major West End firms. The scales on these alligator loafers don’t match across the left and right shoes; these exotic wholecuts were delivered with flaky skins. In a YouTube video, Kirby Allison describes John Carnera’s “twisted last” theory—something I have no doubt exists—but Allison’s back seams angle outward at different degrees. I’ve seen some beautiful shoes come out of John Lobb’s workshop, but some with blobby lasts and nails sticking into the footbed. Foster recently collapsed altogether after buying a factory as part of an effort to expand into ready-to-wear. It’s unclear what’s going on now at the company, except that some associated parties are operating under the banner of Canon.

It’s unclear why major firms seem to be flagging. Whispers in the industry point to skyrocketing Mayfair rents, which have pushed many bespoke firms to focus more heavily on ready-to-wear (think of the ever-expanding RTW lines on Savile Row). Bespoke services and the breathless fashion articles about them are increasingly used to give lower-end RTW lines a halo. Additionally, the decline of tailored dress around the world, including among the social elites, has left bespoke firms with fewer customers than 100 years ago.

Several shoemakers also told me about the problems with wages. “These big firms can’t find quality shoemakers because it’s a shit job,” Wegan says plainly. After the last has been created, it takes a shoemaker about 30 to 35 hours to put together a pair of shoes. Yet, they only get paid about 350 pounds per job, depending on the complexity of the design (that’s roughly $418 given the current exchange rate, earning the shoemaker about $11.94 to $13.93 per hour—below California’s minimum wage). “You can’t pay rent in London, raise a family, and save for the future on an outworker’s income,” says Wegan. “So you have to learn how to do things more quickly. Naturally, you will get faster at this with experience, but you can only go so fast before quality slips. If you find yourself having to make four or five pairs of shoes per week to pay the bills, the quality of each shoe will go down as you cut corners. But if no one complains and sends the shoes back, you think, ‘OK, well, I’ll just keep doing this then because I get paid the same either way.’ That’s how quality slips.”

These experiences have only deepened my conviction that the best work in tailoring and shoemaking nowadays is done by small, independent firms, typically those run by the cutter or lastmaker. These companies are tiny and commonly operate out of a person’s home or an artist’s loft, rather than out of the workrooms located in Mayfair. These companies don’t have the same prestige, name recognition, or celebrity clientele enjoyed by the larger heritage firms, but their work is incomparably better. Additionally, they pay their outworkers more—an important point for people who care about fair wages. The rise of these unglamorous independents has been made possible by an online ecosystem consisting of forums, blogs, and Instagram accounts focused on the finer points of craftsmanship. It’s a remarkable story about how the internet has saved bespoke crafts at a time when this trade could have been swept away by the tide of mass manufacturing, roughly a hundred years after Marx bought his bespoke shoes.

Part two of this story has been published in a separate post.