About ten years ago, I traveled to Naples, Italy to interview bespoke tailors for some stories I was writing for various outlets. When you interview enough tailors, particularly those of an older generation, you will hear the same stories repeated. This typically happens over a strong cup of espresso, sometimes called na tazzulella e café in the local dialect, which is chased down with a small cup of water and a bite of dark chocolate. Whenever you walk into a tailor’s workshop, the first thing they’ll ask you is, “Ve site giè pigliato o’ cafè?” (Have you had coffee?). I was told by a Neapolitan friend that the polite thing to do is always answer in the affirmative. Since I had to interview three or four tailors each day, I went through every day shaking from caffeine. When a tailor makes you coffee, he or she will make two cups — one for you and one for them. Then they’ll sit down with you and proceed to complain.

Neapolitan tailors are worried that the tailoring trade in their area will die out in a generation or two, as young people don’t want to make clothes for a living. They also believe that young people don’t have the time or temperament to perfect tedious tailoring techniques, which require years of practice. Many of these older tailors entered their trade when they were young, some as young as eight years old. Today, such practices are no longer possible because of compulsory schooling. One tailor swore to me that you have to train for at least twenty years before you can make a beautiful suit. “Once someone graduates from university, it’s too late for them to become a tailor,” he confidently told me. I wanted to believe him, so I nodded gravely.

While on that trip, however, I was allowed to tour the backrooms of some notable workshops, including those belonging to Rubinacci and Sartoria Formosa. There, I saw young tailors quietly sewing away. It’s true that the labor pool is shrinking — tailors are dying at a faster rate than they’re being replaced. Several cutters in the United States have told me about their difficulties finding skilled coatmakers in this country, so they’re left bundling pieces of cloth and sending them around the world for making. But young tailors exist, and their scarcity has only made it more exciting to see people entering this trade. In the ten years since I made that trip to Italy, I’ve come to know a few. Here are four operations that I think are particularly interesting.

Fred Nieddu: New Golden Age Tailoring

At the end of 2020, Vulture asked me to write something about the clothes featured in Netflix’s historical drama, The Crown. My article was about how the show used country clothes, specifically waxed cotton Barbour jackets, to signal something about socio-economic class and in/out-group membership. But what really struck me about the show’s costumes, which would have been ill-suited for an article aimed at a more general audience, was the quality of the tailoring. The tailoring in The Crown is spectacular and demonstrates an impressive level of forensic accuracy. In the series, Josh O’Connor’s Prince Charles wears the three-button, narrow-lapel suits that the real-life Prince favored as a youth before switching to drapey double-breasted numbers later in life. I remember being particularly impressed by a mossy green tweed sport coat that O’Connor’s character wore while attending a Scottish folk festival. The coat fit so well that, to borrow Lord Byron’s charming phrase, “it seemed as if the body thought.”

I would only learn later that the clothes were cut by Fred Nieddu, then the head cutter at Timothy Everest and now a freelance pattern maker working under his own firm, taillour (an Old French term for tailor). Nieddu drafted and cut all the leading men’s clothes. This is an impressive feat if you, like me, are enamored with the Golden Age of classic men’s tailoring, a period spanning from the 1930s to the ’80s. Nieddu tells me that he and the costume department heads all agreed that the show’s clothes should give the nod to the past but not necessarily be replications. But it’s striking how much more faithful these clothes are to the Golden Age than even modern Savile Row (which, in my estimation, is now a shadow of its former self).

“Working on The Crown has been incredible,” Nieddu says. “At the beginning of each season, the costume heads and I would meet, discuss each of the leading male characters, and do a huge amount of research. I tend to look for additional photos as I go through the cutting process. In seasons one and two, I changed the way I drafted the patterns from my usual ‘crooked’ shoulder method to a much ‘straighter’ shoulder in the style of Frederick Scholte. We even cut the canvas on the bias, as that was the way back then to achieve a very soft, drapey coat. Along with making all of the show’s suits, overcoats, highland dress, and formalwear, I’ve also made boots, capes, riding clothes, various children’s suits, and 1980s styled ski suits. Working on the show has been a real pleasure, and quite a challenge at times.”

As a boy growing up, Nieddu didn’t think he would ever become a tailor. He loved drawing and went to the University of the Arts London to study illustration. But upon graduating, he faced the harsh reality that professional illustration jobs typically involve sitting behind a computer screen, editing digital pixels through programs such as Adobe Photoshop and InDesign. As a self-described technophobe, he decided to go into bespoke tailoring instead, where his penchant for working with pen and paper seemed better matched if he was also willing to pick up shears. He parlayed an old clothing job into an apprenticeship at Alexander Boyd, where he would spend the next five years learning how to cut and sew under the direction of Clive Phythian, a former military cutter at Gieves & Hawkes. Later, he went to work at Timothy Everest, where he made the opposite style of clothing for musicians and movie stars.

“Timothy Everest’s thing was to never really push a house style on anyone,” Nieddu explained. “It was always about what is correct for a particular customer. I liked the idea that bespoke was really bespoke. The company’s style obviously moved slightly with fashions, but it’s one of the most flexible tailoring companies I’ve ever known. Before the film work took off there, the experimentation we did for customers prepared me to think outside of the box. Learning from so many different cutters, and being quite obsessive about clothes in general, has helped me feel confident about mixing and matching different methods of working.”

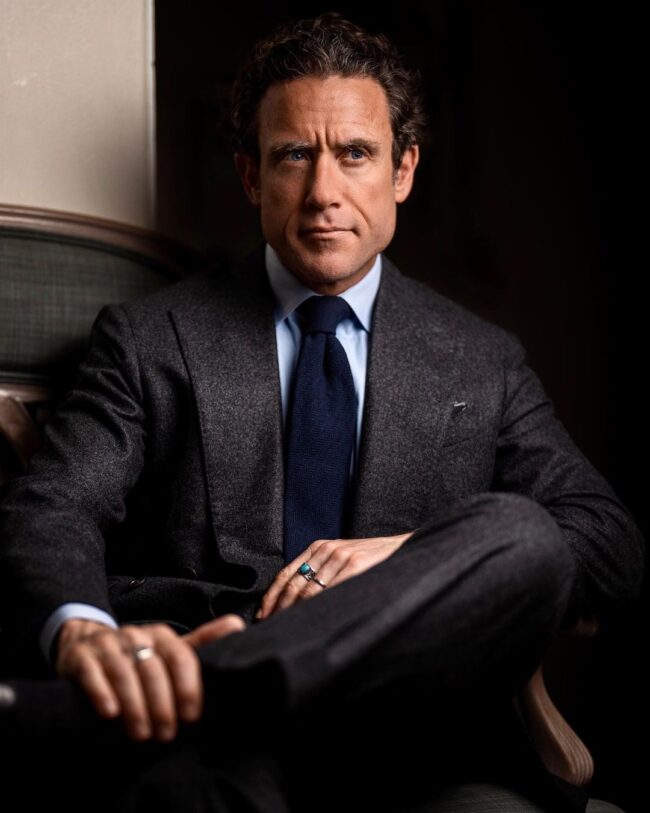

Nieddu has made clothes for some notable online style figures, such as Simon Crompton, Tony Sylvester, Kenji Cheung, Alex Natt, and Aleks Cvetkovic. In an article at Robb Report, Cvetkovic writes glowingly of Nieddu’s work. “Nieddu’s approach to bespoke tailoring is more open-minded than some of his peers. He’ll happily cut you a jacket that’s big, bold, and structured, or create something totally deconstructed and slouchy. His preferred house style sits nicely in-between these extremes — blending his Italian roots and Savile Row training.” Nieddu tells me that he doesn’t impose a house style on anyone, but prioritizes comfort through his use of high armholes and soft Italian canvas. “I also like one-button sleeves and putting an angle on patch pockets,” he says, “but I wouldn’t impose these details on someone unless they asked me for advice.”

Of all the tailors in Britain right now, whether new or old to the scene, Nieddu is the one I want to use most. It’s for the simple reason that the things he’s made for The Crown and Cvetkovic most closely resemble the clothes I’ve long admired in black-and-white photos of the Golden Age. Friends tell me that his creations are soft, which I find surprising given how much shape is given through the shoulders and chest, an effect typically built up through the generous use of haircloth, canvas, and padding.

“The trick, if it is a trick, with the shoulder I cut is to keep it very close to your natural shoulder,” Nieddu tells me. “I tend to cut a lot of ease into the back shoulder and displace the seams to bring the shoulder seam forward for more comfort. The pad we make is roughly 1/4″ thick before being pressed. So by the time the garment is finished, there isn’t much there. The wadding is also made of two-ply demette with no canvas. This adds another touch of traditional English bespoke without a huge amount of crown.” There’s something classic and modern about Nieddu’s tailoring, recalling the best of the Golden Age without looking like a historical costume. I was also slightly amused to hear Nieddu searching for words when talking about his love for Ralph Lauren on HandCut Radio’s podcast — a sign that his love for the brand (a love I share) is difficult to articulate. I hope to experience his tailoring one day for myself, and perhaps, have a conversation about our shared love for the greatest menswear brand.

Sartoria Salabianca: Carrying Forward Florentine Style

When reading about tailoring during the 20th century, it’s striking to see how often this trade has run perilously short of manpower. In 1948, decades before the business casual movement would sweep the suit from white-collar offices, a cutter named John King Wilson lamented that the tailoring trade was “in danger of extinction.” “[Bespoke tailoring] is the oldest and will, I believe, be the last to go,” he predicted, “as one by one [these crafts] are ruthlessly destroyed at the guillotine of the industrialist, the politician, and the scientist, all of whom appear to take a sadistic delight in seeing such majestic but melancholy heads rolling in the dust. Can we survive? Assuredly, yes. But we shall do so only so far as we succeed in invigorating the trade with more recruits as craftsmen.” King implored his fellow tailors to recruit from their children. “Where could we better seek than amongst our own sons and daughters whose roots are already here? Unbounded possibilities are theirs in an interesting, not overworked yet well-paid career.”

Much has changed since Wilson wrote that in his book, The Art of Cutting and Fitting: A Practical Manual, published during the immediate post-war period. Yes, there are still possibilities in a career as a tailor, but perhaps not unbounded. “Not overworked yet well paid” is not even a remote possibility. As such, European tailoring houses have faced an even more acute labor shortage in their domestic market. Thankfully, this shortage has been temporally filled by East Asian immigrants who sojourn to Britain and Italy to learn from master tailors and shoemakers. Such artisans include Yohei Fukuda (of his eponymous company), Kotaro Miyahira (Corcos), Noriyuki Ueki (Ciccio), Yusuche Ono (Anglofilo), and Noriyuki Higashi (Raffaniello). A friend recently told me about Zhang Xiao, who apprenticed at Musella Dembech and now runs her own workshop in the Chinese port city of Qingdao. “The quality is quite high, and it’s nice to have a Chinese independent,” he told me.

Hojun Choi comes from this long lineage of international artisans. When he was still living in South Korea, he learned about Florentine tailoring and became particularly enamored with Liverano & Liverano. “I wanted to learn how to make this style of coat, where there’s no front dart, but no Korean tailor at the time could teach me since they didn’t train in Italy,” he told me. “So I decided to go straight to Italy and ask Liverano for an apprenticeship. After begging several times, he finally agreed. I spent seven years at Liverano as an apprentice and then trained an additional year under Francesco Guida. The more I learned, the more I wanted to make my own style. So I started my atelier, Sartoria Salabianca, named after the grand hall at Palazzo Pitti, where the first fashion show was held in Italy.”

Longtime readers of menswear blogs will be well-acquainted with Florentine tailoring. Like the city from which it hails, Florentine style sits somewhere between the types of suits you’ll find in Milan and Naples. Milanese tailoring is known for its structure and angular lines, making it well-suited for business in the industrial north. By contrast, Neapolitan tailoring is known for its soft lines, casual style, and deconstructed make. Since Neapolitan coats typically have minimal structure, they often, but not always, fit a bit slim and narrow through the shoulders. Florentine tailoring sits somewhere between these two traditions. It’s structured but not rigid; soft but not narrow. The shoulder line is typically a little padded so that it’s soft and sloping but extends just off the shoulder bone in a straight line. You can always tell when a coat is Florentine when it’s missing a front dart, a technique that makes it well-suited for patterned fabrics. They also typically have short, rounded silhouettes with curvy quarters that blow back towards the hips, and then curvaceous lapels that look like inverted crescents.

Choi recently opened an atelier on the eastern edge of Florence’s historic city center. It’s located in an old neighborhood with lively food markets, a nearby flea market, and plenty of artisan workshops (including his). He also travels to Paris, Seoul, and Bangkok for trunk shows (the photos above show Decorum co-founder Sirapol Ridhiprasart wearing Salabianca’s bespoke suits). I love that Choi is carrying forward one of the most beautiful tailoring traditions. These coats have tremendous shape and elegance. The front doesn’t have any visible darts, and even semi-casual garments such as sport coats feature jetted pockets, visually cleaning it of patches and flaps. The lapels have so much curvature where they break that they almost look like they’re blooming out of the buttoning point. Choi tells me that this curvature is achieved through the careful use of ease and tension while hand-sewing. “The stitches are quite small, some a matter of millimeters. But when you add up all these small stitches, they can make a big impact,” he says. “I think elegance is about not doing too much — never overworking the details or overdoing the silhouette. Some people might consider my suits to be too boring or simple. But doing something simple and well is the most difficult.”

I Sarti Italiani: Affordable Sicilian Tailoring

There’s a beautiful, mythical story about tailoring that goes something like this: once upon a time, the world was pristine and pure, and skilled tailors lovingly crafted clothes by hand for local customers, often dressing generations of men within the same family. Sometime in the mid-19th century, the evil ready-to-wear industry emerged from the shadows. Standards slipped, sizes were standardized, and nothing fit well anymore. A hundred years later, made-to-measure offered people the halfway point between these two extremes. Made-to-measure is often characterized like that scene from Woody Allen’s 1973 film Sleeper. We imagine that robot tailors flip the switch on a whizzing, thumping, suit-making machine. An ill-fitting suit with overlong sleeves is spat out at the other end, and you’re sent along your way.

If only the world were so simple. In reality, many tailoring companies exist between the Platonic ideals of handmade bespoke and machine-constructed made-to-measure. I Sarti Italiani is a wonderful example. My friend Peter Zottolo found them six years ago when he and his wife, Angela, vacationed in Sicily. Peter actually visited a few tailors while on that trip. But like many bespoke craftspeople, most of these tailors were unwilling to change their ways. “They made nice suits, but their house style was fossilized in the ultra-slim silhouette of the early aughts,” Peter told me while we had coffee in San Francisco. “They would take input and say they would do this or that, but the changes weren’t there when the suit came out.” By contrast, Salvatore Ioco, the young face of I Sarti Italiani, was willing to listen.

With a showroom in Palermo, the capital of Sicily, and a small factory in nearby Montelepre, I Sarti Italiani is a unique tailoring workshop that can make a wide range of things. They can do bespoke or made-to-measure, fully canvased or fused, hand-tailored or machine-made. The company’s bread-and-butter is in producing made-to-measure garments for local Sicilians, who typically want one or two affordable suits to wear to weddings and church services. The company’s house style is what Italians would describe as la moda (the fashion). The jackets are trim and short, built with a high gorge, and designed to be worn with trim, pegged trousers that sit just over the opening of the wearer’s lace-up shoes. When Peter approached them, he said he wanted something more like “Cary Grant.” “Not exactly like Cary Grant, but in that direction.”

It’s unusual for a tailoring company to take direction like this. Men who have a lot of experience working with tailors often repeat this nugget of wisdom: “don’t stray far from the house style.” A tailor’s house style is their signature, and it’s born from many years of repeated movements by the same pair of hands. Choosing a tailor with a strong house style can minimize the element of surprise and result in a look that’s difficult to achieve off-the-rack. Makers with a clear point of view are also typically better at their craft. Those who say they can make anything are often a master of nothing (customers who think they can step into the role of being a designer are often even less well suited for the role). As such, it’s wise to choose a tailor based on their house style and not stray far from it. You can adjust things on the margins — asking for a slightly shorter jacket, just as you might ask for a dish to be made less spicy. But if you go to a British tailor and ask for an Italian coat, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment.

There are some rare exceptions. To successfully change a tailor’s house style, you need a tailor who’s open to experimenting and a customer willing to put in successive orders, each time modifying the cut until a new style is achieved. It’s easier to implement one or two changes based on the previous order, rather than dramatically changing a tailor’s cut all at once. You can see this process play out on Peter’s Instagram. One of his first orders was for this blue tweed sport coat, which is trim and short (and also fused). A few orders later, he commissioned this corduroy suit, which fit a little fuller through the chest but was still a little narrow through the shoulders (that garment is fully canvassed). Many orders later, and we have a newly developed house style with slightly extended shoulders, fuller chest, and fuller sleeves. Peter was also able to get Salvatore to cut the internal chest piece on the bias, much like a British tailor would for a drape coat. This gives the chest a bit of roundness. Such internal changes would not be possible if Salvatore were not an open-minded tailor.

Having seen these changes occur in real-time and being impressed with the final results, I had enough confidence to order a bespoke cotton suit from I Sarti Italiani a few years ago. The suit has since become one of my favorites. For me, it’s a knockabout suit. A fun suit. A suit I can wear without having it pressed every few months. With Peter’s help, they’ve developed a new house style that feels comfortable and looks flattering on a wider range of figures. Their tailoring confers that v-shaped silhouette that gives the impression of a more athletic figure even when there is none.

The best thing is the price. I Sarti Italiani’s tailoring costs about a third of what US customers would pay for something similar elsewhere. To understand how they do this, it helps to review what should be the Gold Standard for bespoke tailoring.

Theoretically, a bespoke pattern should be drafted by hand and from scratch. This can be done by using drafting formulas or drawing it freehand (a technique known as rock of eye). Afterward, the long seams are sewn by machine, and the other parts are executed by hand: attaching the sleeves and collar, making the buttonholes, and pad stitching the chest and lapels. Pad stitching is when a tailor picks up multiple layers of cloth, skillfully using ease and tension when sewing short stitches to transform a two-dimensional piece of fabric into a three-dimensional form. Pad stitching gives the chest and lapels shape so that a suit jacket or sport coat doesn’t fit like a limp dress shirt. Since bespoke tailoring represents the highest level of craft, this process should be done by hand.

In reality, many bespoke tailors have long abandoned this Gold Standard. Even on Savile Row, you can find pre-made block patterns in the backrooms of some of the most prestigious tailoring firms. These tailors justify their use of block patterns by saying they adjust them by hand, but I’ve found that defects in the block pattern still show up in a wide range of orders. Additionally, it’s not uncommon to see tailors machine pad their coats nowadays. Look at this suit from A. Caraceni, one of the world’s most reputable bespoke tailoring firms. The finishing is impeccable. The buttonholes, pick stitching, besom pockets with mezzaluna tacks, and curved barchetta pocket have been meticulously executed by hand. Menswear writers love to breathlessly swoon over this type of handwork. It’s visible and uncommon on the ready-to-wear market, which allows them to talk about the virtues of benchmade tailoring and Old World craftsmanship. But when you take the suits apart — which no regular customer would ever do — you can peer under the hood and see machine padding. You can tell the lapels are machine-padded because the stitches are backed by a straight line and all angle upwards, rather than following a herringbone pattern indicative of handwork. On this Caraceni suit, there’s even a fusible across the lapel.

I Sarti Italiani also uses a combination of bench tailoring and industrial production. They create a pattern using a computer-aided design program (CAD), typical of the made-to-measure. At the same time, they do three fittings, a process characteristic of bespoke, which gives them the ability to change tiny details such as the gorge height. Additionally, the internal layers, up to four, including the chest piece, are sewn together by machine. This internal structure is first attached to the coat’s shell fabric by machine and then ripped out after the fittings and done by hand (a process known as “ripped and smoothed,” which is also part of the title of Richard Anderson’s book).

Whether pad stitching by hand or machine makes any measurable difference is the kind of thing that inspires fierce arguments among tailors. As a customer, the only thing that matters is whether you like the resulting garment. I Sarti Italiani represents this exciting and emerging space between the Platonic ideals of handmade bespoke and machine-produced made-to-measure. Their combination of bench tailoring and industrial production allows them to offer custom tailoring at a more accessible price point, which has made me more comfortable with experimenting. I don’t think I would have ever ordered a bespoke cotton suit at a more expensive tailoring house. But since trying this one, I’ve put down deposits for four more suits: a single-breasted in brushed tan cotton, a double-breasted in chocolate linen, another double-breasted in olive gabardine, and a single-breasted in walnut cavalry twill. At their price point, I Sarti Italiani has brought me back to that experimental phase in tailoring that makes this hobby so fun.

Kyosuke Kunimoto: The Rebel Tailor

When Tommy Nutter and Edward Sexton opened the doors to Nutters of Savile Row in 1969, they liberated the suit from nearly a hundred years of Mayfair tradition. Until that point, the standard suit was staid, “designed to deflect attention away from the male form beneath the layers,” not unlike how the closed doors and shuttered windows at each Savile Row tailoring shop protected the privacy of insiders. Tommy Nutter broke with this tradition by creating dazzling, street-facing shop windows to lure in the random passerby — to the horror of his conservative neighbors — and combining new-Edwardian flamboyance with old-school craftsmanship. His suits were full of youthful fantasy, rebellion, and glamour, and they attracted members of the glitterati and the people who wanted to dress like them.

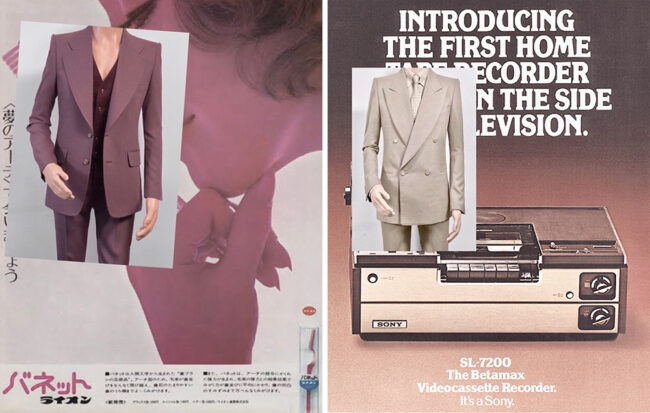

In some ways, Kyosuke Kunimoto is like the new Tommy Nutter. He’s an enigma, a mystery wrapped in a riddle. No one in the menswear industry seems to know much about him, including the editors of The Rake Japan. His indecipherable website looks like one of those experimental web designs that edgy teenagers put together in the late 1990s, where hyperlinks were hidden behind Whac-a-Mole jpegs and cheesy 3D graphics spun around indefinitely. Kunimoto-san’s website contains just a digital thumbprint, a link to his email (which mostly goes unanswered), and pictures laid out like faded advertisements buried inside dusty 1970s magazines. Despite having a low profile and rarely granting interviews, Kunimoto-san, like the original Nutters of Savile Row, stokes the ire of his fellow tailors. A few months ago, I reached out to some cutters to ask them questions for this post. When one heard that Kunimoto-san would be part of it, he pulled out, saying that he didn’t want his name to be next to his. “I don’t think his work is very respectable,” he said dryly.

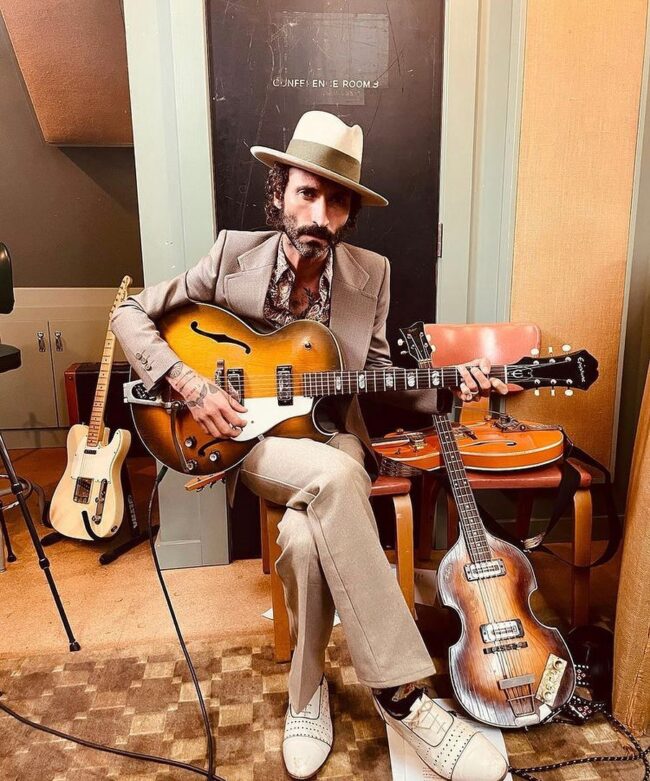

Respectability is a running theme among conservative tailors and customers, and if you’re after a respectable-looking suit, you should not come here. Kunimoto-san doesn’t make clothes for business people who want to climb the corporate ladder; he makes showbiz clothes for rising stars. Cautious suits in sober colors such as navy and charcoal have been swept away in favor of riotous garments in lavender and vermillion (as worn by Jay De La Cueva and Enrique Bunbury, respectively). At last year’s Soul Train award show, Leon Bridges wore a sumptuous black velvet suit finished with tonal piping. Bridges also owns one of Kunimoto-san’s limited edition black leather sport coats (one of five), made with double stitched edges and triple patch pockets. Some years ago, Sean Lennon introduced Mark Ronson to Maison Lance, Kunimoto-san’s tailoring company. Ronson has since flown to Japan to order various custom clothes, including his wedding suit, nightclub suits, and a brown glen-checked double-breasted suit carefully made so the line of the check follows the edge of the peak lapel.

It takes a lot of skill to drive a line between tradition and subversion. This is something that less experienced dressers sometimes miss when they take dress purely as a form of artistic expression, festooning their otherwise conservative outfits with some gimmick such as purple shoes. When you look closely at Nutter and Kunimoto-san’s bombastic creations, you can see a coherent whole connected to traditional British style. Their suits and sport coats exaggerate the proportions of British hacking jackets, originally made for horseback riding. Those full-bodied jackets have long, leafy silhouettes with wide skirts made to neatly spread out over a horse saddle. Nutter and Kunimoto-san added masses of “shape and flare” to that silhouette, tightened the waist, and widened the lapels so that they almost graze the sleeve heads. The result is a “louche-but-sharp flamboyance” that’s still culturally legible.

One of the things I admire about Kunimoto-san is that his work sits at the intersection of many streams. As a graduate of Central Saint Martins, there’s a dash of designer fashion in his creations, similar in flavor to Tom Ford’s Gucci. At the same time, there’s a clear understanding of traditional tailoring. Kunimoto-san is also culturally attuned and looks to cultural creators as friends, not enemies. When he graduated from art school in 1996, one of his first self-funded projects was to create twenty-four pairs of audacious Beatle boots made from antique fabrics, such as 200-year-old printed cotton and 100-year-old German velvet traditionally used for upholstery. He then cold-contacted Vincent Gallo through Gallo’s website, attaching a photo of these boots and writing: “If you like any of them, I’m happy to make some clothes for you.” The shot-in-the-dark worked, and he now makes things for musicians, artists, and people in the film industry. Kunimoto-san brings together so much of what made avant-garde tailoring in the past so appealing: a willingness to be bold, a familiarity with tradition, and an interest in the cultural movers and shakers who can give unusual styles meaning.

For readers based in the US, taillour and Sartoria Salabianca are now visiting New York City for trunk shows. I Sarti Italiani also visits NYC, along with San Francisco. Additionally, I will be doing a podcast series with Blamo!, where I’ll talk about these new tailors and other clothing-related matters. A new podcast will drop every other month and be available for Blamo’s Patreon subscribers starting at $5/ month.