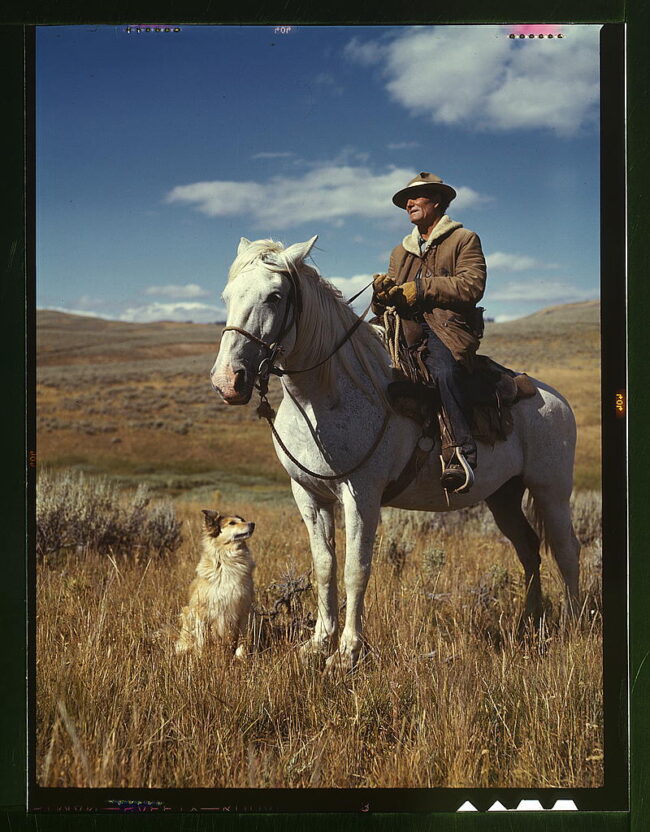

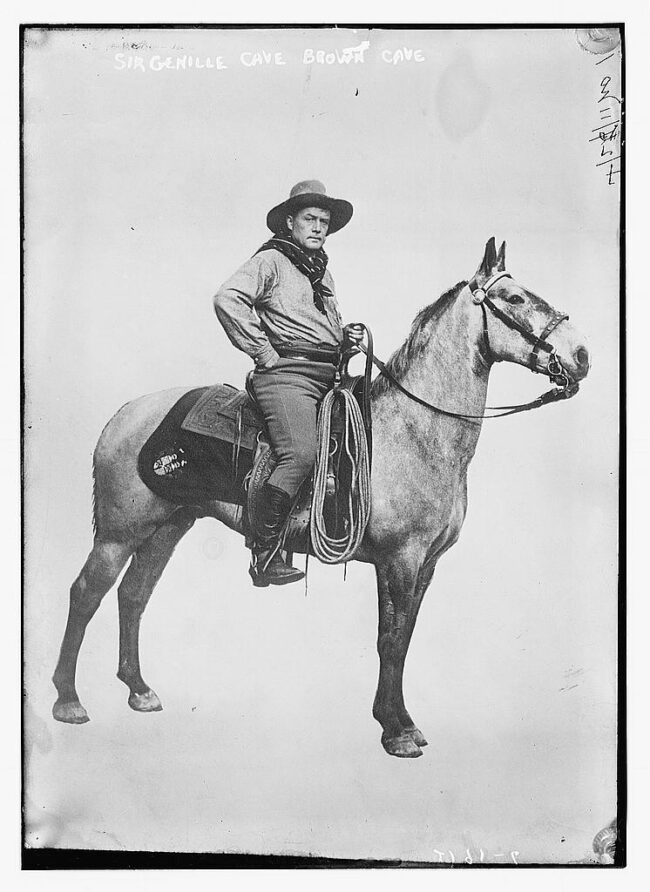

Before arriving in the United States, Igwe Udeh had never seen a cowboy in real life. He didn’t even know they still existed. When he was a child in Nigeria, peddlers used to come through his small town, show spaghetti Westerns on a projector, and sell American products to amped-up audiences. Udeh loved those films and knew all the lines to every Clint Eastwood classic. But to him, the cowboy was a mythical character — a symbol of a bygone era in the American West. That is, until the autumn of 1980, when he looked up from his desk at the University of Oklahoma and saw a tall, slender man strolling into the classroom. This man wore a red plaid shirt, thick leather boots that clicked as he walked, and a wide-brimmed hat that obscured his face. When he sat down, he gently took off his hat and set it on the seat next to him. As other students poured into the classroom, no one dared to sit there. Udeh was in awe of this man’s confidence.

Udeh left Nigeria to pursue a graduate degree in economics at the University of Oklahoma. But when he arrived, he found that he was the only black man in his program and one of the few in the town of Norman. None of the local barbers knew how to cut Udeh’s hair, so he let it grow into an Afro. Some of the locals also had a hard time understanding Udeh through his thick Nigerian accent. When Udeh went to church, he wore his most traditional garb: a colorful West African pullover known as a dashiki. “No one would talk to me,” he recalls in an interview. “They’d look at me like, ‘Why are you dressed like that?’ I’d sit down and people would get up one by one from the pews and move somewhere else. I’d leave feeling rejected and alienated.”

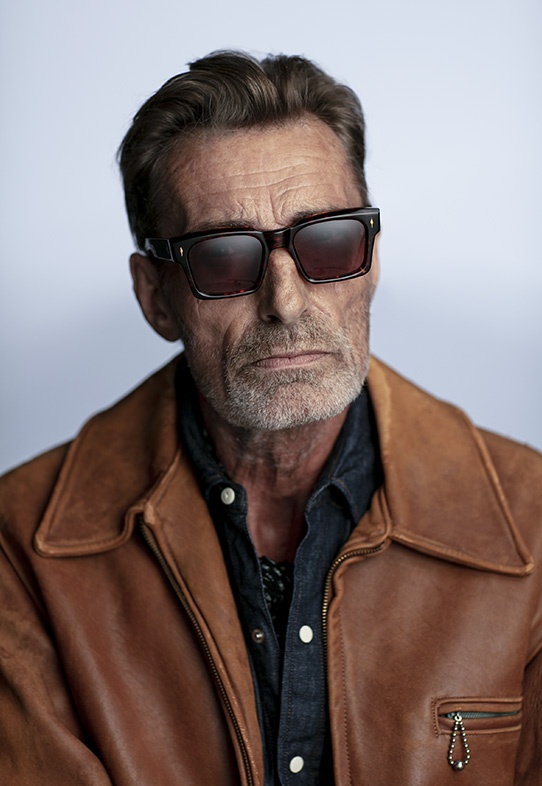

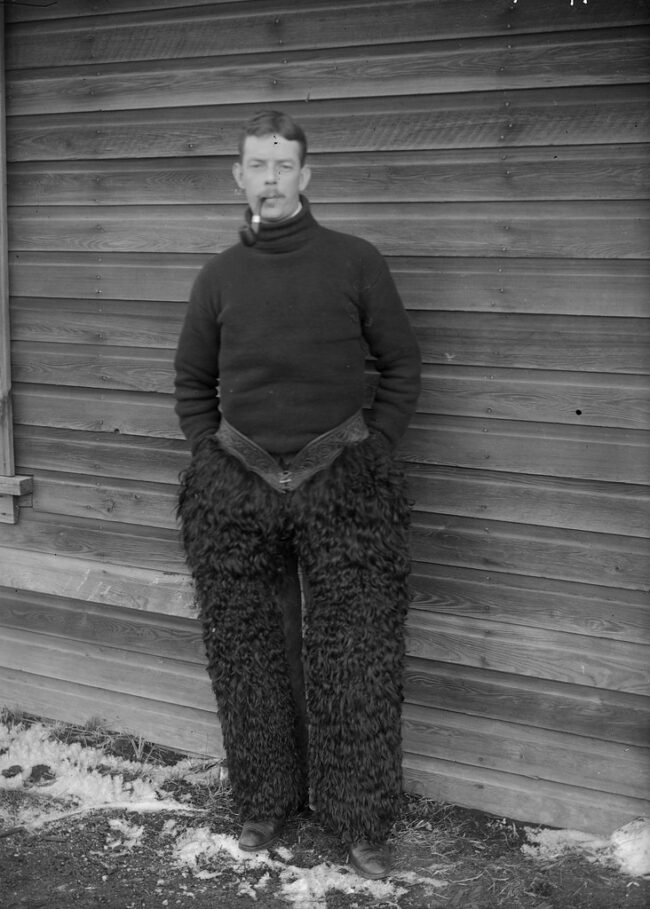

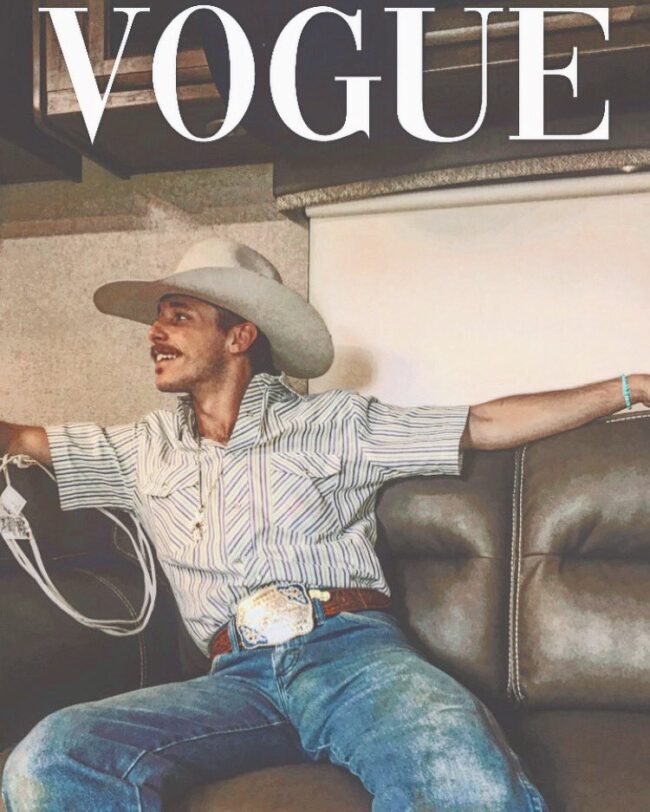

Udeh wanted to assimilate, but in a way that would still allow him to express his African identity. As a Nigerian of Igbo descent, Udeh recognized some commonalities between his background and the American cowboy. Both cultures are deeply connected to the land. They are also both known for their strong, independent spirit and blunt manner of speaking. So Udeh went around to the local thrift stores to shop for some cowboy clothes (not difficult, as that’s all they sold). He purchased plaid flannel shirts with shiny pearl-snap buttons, second-hand blue jeans, and cowboy boots that made him stand taller. He even bought the biggest Kawasaki motorcycle he could afford — his own iron horse — but found he couldn’t wear the helmet because his Afro was too big. His appearance tickled local Oklahomans who had never seen a foreigner dress this way. “The first time I walked into a classroom in my new cowboy getup, someone said, ‘Look at that! Igwe wants to be a cowboy.’ I smiled and replied, ‘Yes, I do.'”

Although the cowboy comes and goes as a pop-cultural force, his appeal remains a slow, constant hum throughout American culture, never entirely going away. From the 1940s through the ’70s, the slow strumming guitar of Hank Williams, the ebullient yodeling of Roy Rogers, and the wild, colorful creations of tailors such as Nudie Cohn, Nathan Turk, and Manuel Cuevas enthralled Americans. During the 1970s and ’80s, television shows such as Dallas and Bonanza were Americana fixtures. John Wayne is so elevated as an American hero that there’s a California airport named after him, complete with a nine-foot, bronze statue of him that greets you on the arrival level.

Even foreigners hold a special love for the American West. When Sergio Leone released his blockbuster hit A Fistful of Dollars in 1964, the film spawned an entire European film genre about the laconic American gunfighter. George Balanchine, the Russian-American ballet choreographer who co-founded New York City Ballet, held a deep fondness for his adopted country. He wore distinctive Western styles, such as string bow ties, snap button shirts, and smile pockets. He was known for mashing together disparate elements for his ballets, often drawing on American material. In Square Dance, dancers gracefully leapt to Vivaldi while a live square-dance caller shouted out the steps (in earlier versions of the show, orchestral members dressed as fiddlers). In Western Symphony, Balanchine celebrated the romance of the Old West by dressing ballet dancers as cowboys and saloon girls. When asked whether Stars and Stripes has a story, Balanchine dryly answered, “yes, the United States.”

What is it about the cowboy image that makes it so alluring? Millions of people who have no experience in the countryside see life on a ranch as enviable, even noble. Much of this has to do with how the United States has mythologized its history. Partly rooted in reality and partly in fiction, this is about the creation of the American identity.

THE MAKING OF A NATIONAL HERO

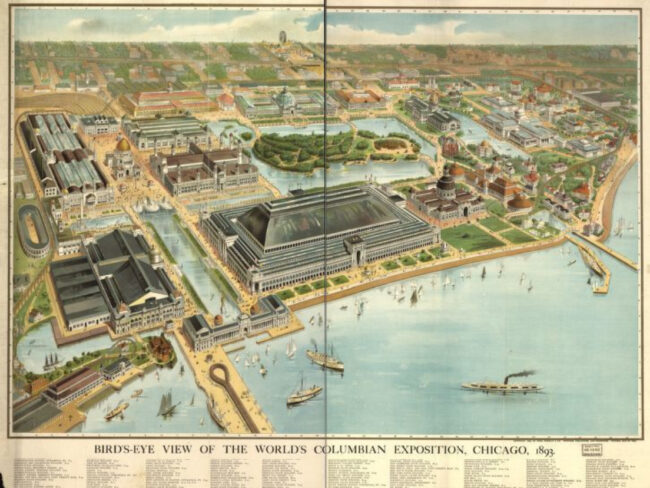

In 1893, during the Gilded Age of American industrial growth, organizers put together the Chicago World’s Fair to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. They turned 633 acres on Chicago’s South Side into a “neo-Classical, Romanesque, Beaux-Arts, Venetian fantasyland.” At this luminous “White City,” attendees experienced many “firsts” — tasting the first Cream of Wheat, Juicy Fruit, and Pabst Blue Ribbon beer; seeing the first dishwasher; and riding the world’s first moving walkway and Ferris wheel. The American Historical Association also held a special meeting to present a series of papers at the fair. One of those presenters was Frederick Jackson Turner, a newly minted John Hopkins graduate who wrote his doctoral dissertation on the Wisconsin fur trade. No one expected his presentation that day to be of any importance — indeed, he was the last of the five presenters on his panel — but his speech transformed American culture for nearly a century.

Turner’s presentation came three years after the Superintendent of the US Census Bureau announced, almost in passing, that the influx of homesteaders, ranchers, and miners along the Western part of the United States meant there was no longer an unbroken line of “uncharted territory.” In other words, the frontier was closed. This announcement so impressed Turner that it inspired him to write his essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” which would later become the first chapter of his book. Turner argued against the Germ Theory, which was a commonly held idea at the turn of the 20th century that political habits are innate racial characteristics. Germ theorists believed that Americans formed their democratic institutions because they descended from Anglo Saxons, who in turn came from ancient Teutons. Thus, the origins of American democracy can be genetically traced back to a Germanic forest, like Continental seeds blowing in the wind and eventually germinating in North America.

Turner didn’t believe in this genetic determinism. Instead, he argued that Americans cut off their European roots when they were on the frontier. His thesis is simple: the experience of migration and westward expansion “produced the practicality, energy, and individualism that defines the American character.” The English families who boarded ships in London and came to America in 1620 ended up founding Boston, Jamestown, and New York City. In learning how to survive in this new environment, they no longer saw themselves as English but as Bostonians, Virginians, and New Yorkers. When some left and moved westward, their identities were reshaped again, each time through subsequent waves of migration. First were the explorers, then frontiersmen such as fur trappers, then land users such as cowboys, and finally settlers such as farmers who arrived to live on the land.

As the frontier pushed westward, the country’s identity and values were forged on the “outer edge of the wave.” On the frontier, there’s no need for old, dysfunctional customs, established churches, or inherited titles. People learned how to survive by being fiercely independent and entrepreneurial. As Turner writes: “[T]o the frontier, the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and acquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind […] that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism […] that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom[.]” From this, America could not help but form a polity around the values of liberty, equality, and rugged individualism. “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development,” Turner wrote in his opening.

Of course, there are some problems with Turner’s thesis. Turner saw the frontier as a whetstone for the American mind. His thesis implies an inevitable decline after the closing of the frontier, which never happened (the 20th century proved to be America’s most significant). Turner’s thesis is also too simplistic. If settlers shed their European identity so quickly and readily at the frontier, what stopped the frontier identity from breaking down again in the many subsequent waves of American development? Most strikingly, Turner glossed over Native American genocide — at some points, he seemingly celebrated it. In his opening, he describes the frontier as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization.” Echoing the ideas of Manifest Destiny, Turner saw the history of the American West as a triumphal narrative about how rugged white men brought civilization and democracy to open and free lands. In reality, westward expansion was often about violent conquest, not peaceful settlement.

Turner’s reductiveness, revisionism, and ethnocentric biases have made him less popular in academic circles in recent years, but his cultural influence has been immense and remains today. Turner gave Americans a coherent narrative about their origin. In telling a story about how pilgrims shed their European lineage, he gave American exceptionalism a credible voice. He also made the frontiersman not just a character in the nation’s expansion, but a central figure in the formation of its identity. The quintessential American wasn’t the New York financier or Bostonian merchant, but the Texan cowboy on the frontier.

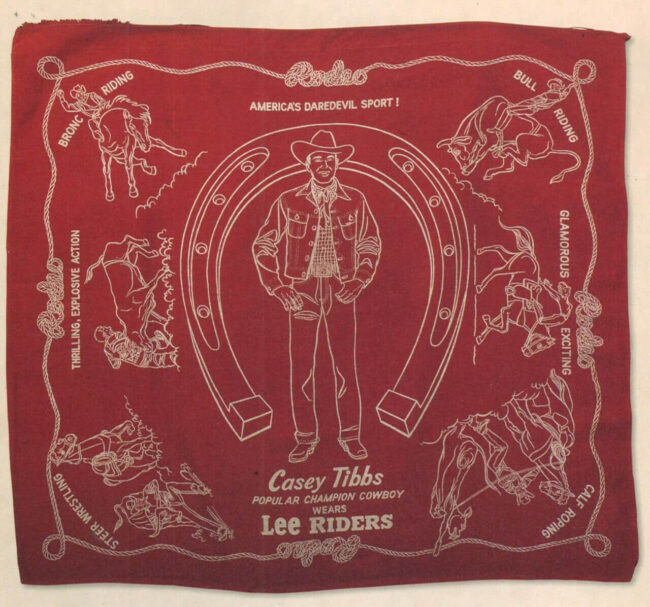

As historian William Appleman Williams wrote, Turner’s ideas soon “rolled through the universities and into popular literature like a tidal wave.” Eight years after Turner presented his paper, he had nine book deals. By the time he passed away in 1932, an estimated sixty percent of American universities taught Turnerian courses. By elevating the cowboy as a national hero, he also helped jumpstart the Western genre. Nine years after Turner published his frontier thesis, Owen Wister published The Virginian, the first Western novel. The Virginian is about a tall, young ranch hand with a deep personality and an ongoing romance with a frail East Coast woman who’s not used to the Wild West. Being a virtuous character, this cowboy resists the temptation to run down his enemies, but is eventually forced into a climactic gun dual.

Wister’s book set the template for the Western storyline, which has been endlessly repeated through books, films, and television shows. Americans couldn’t get enough of this imaginary hero — simple in manner, righteous in character, trustworthy and gentle, but strong when necessary. Hollywood churned out hit after hit, each movie traveling along the same well-rutted road: Dodge City (1939), Red River (1948), Rio Grande (1950), Shane (1953), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), and many more. For decades, Westerns were among the top ten highest-grossing films each year, outpacing any other genre. Americans still pine for this male archetype. In the fourth season of The Sopranos, Tony Soprano barks in the car: “What the fuck ever happened to Gary Cooper? Now there was an American. The strong, silent type.”

This narrative about the Wild West proved untenable starting in the 1960s. With the countercultural protests, student movements, and racial tensions exploding into wild infernos across the country, many Americans began taking a more critical look at Hollywood’s depictions of ethnic minorities. This was especially true of films that are supposed to have some footing in history. During the Wounded Knee Occupation of 1973, some 200 Native Americans and followers of the American Indian Movement (AIM) forced white Americans to confront a much harsher reality about this country’s past. Public opinion polls revealed widespread support for Native Americans at the siege. That same year, Marlon Brando famously declined to accept his Oscar for his role in The Godfather, sending Sacheen Littlefeather to speak for him at the event instead. With the horrors of the Vietnam War playing out on television screens, many also became disillusioned with the idea of American exceptionalism.

In these two turbulent decades, it’s no wonder that the Western genre started to have an identity crisis. Filmmakers could no longer depict cowboys as virtuous heroes galloping into towns, dispensing justice, and acting as harbingers of civilization. So, they started to play around with the genre and created the Revisionist Western. Little Big Man (1970) and Jeremiah Johnson (1972) featured more humanistic portrayals of Native Americans (although Little Big Man still falls into tropes about noble savages). A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and Young Guns (1988) relied on the antihero, while The Wild Bunch (1969) simply had no heroes. Blazing Saddles (1974) is a satirical comedy on the genre. One of the highest-grossing revisionist films in the last decade, Django Unchained (2012), flips the script: a black slave partners with a dentist-turned-bounty hunter to track down three outlaws who work as overseers.

A MORE COMPLEX COWBOY IMAGE

One of the strange things about the Westernwear revival in the last year is that it sits alongside one of the most fraught periods of post-war American politics, particularly when it comes to sensitivity and inclusivity around racial issues. Turner’s thesis gave us the semiotics of Western dress. Much like how the post-war Ivy Look is associated with WASPy privilege and elite education, cowboy boots are synonymous with an American brand of self-reliance, practicality, and optimism. It’s partly for these reasons why so many people are drawn to these styles. At the same time, Turner’s critics have poked holes in the frontier myth. Even if you’ve never read New Western historians such as Patricia Nelson Limerick, Richard White, or Donald Worster, you may find something uncomfortable with the squeaky clean image of the cowboy as a hero.

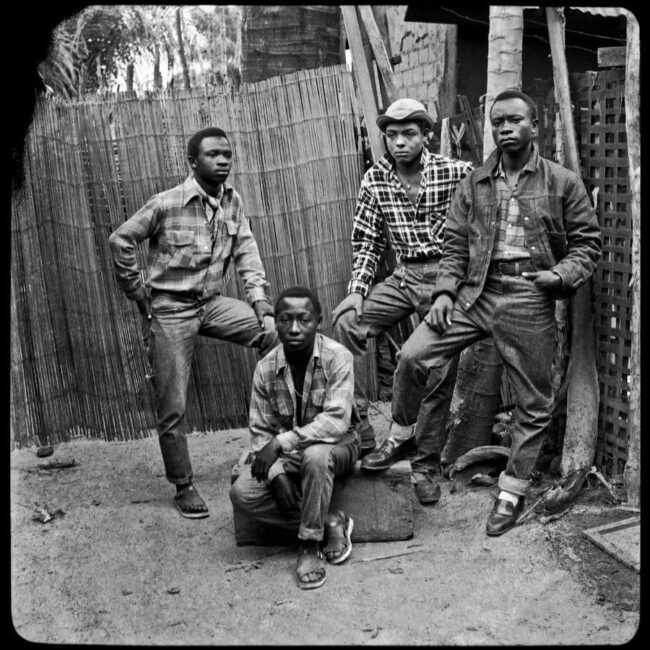

But it would be a mistake to write off these styles completely (and ironically Turnerian, as it assumes there’s only one narrative about the West). In her book The Legacy of Conquest, Limerick tells a much more nuanced and multi-faceted tale of the American West that includes Plains Indians, Hispanics, Chinese, Japanese, and blacks. For a time, the West was one of the most ethnically diverse sections of the country. As Richard Bernstein wrote in The New York Times: “The regional political establishment has become increasingly receptive to a vision of the West as a place of pitiless struggle involving not only Gary Cooper white guys, but just about every human type — Indian chiefs and black newspaper men, society dames and prostitutes, missionaries and Chinese real estate investors, fur trappers and squaws.” That diversity lives on in the modern Western genre, as this culture has been indelibly shaped by Native American silversmiths and weavers, Spanish vaqueros, black cowboys, white cowboys, and performers of every color.

Larry Callies used to be a twanging country singer with a promising music career until a rare condition called dysphonia stole his voice. These days, he’s the curator and docent of his own Black Cowboy Museum in Rosenberg, Texas, where he works to preserve a section of this country’s unsung history. Callies likes to remind people that one in four cowboys during the pioneer era was black. In fact, the word “cowboy” was originally a pejorative for black farm workers — their white equivalents were known as “cowhands.” “The first cowboys were slaves,” Callies explains in an interview. “My Grandpa was a slave. My Grandma was a slave. They called us ‘boys.’ A white kid of a slave owner could be 15 years old, and you’d be 50-something years old, and he’d still say, ‘Come here, boy,’ and you’d have to come. On the plantation, you had ‘house boys’ that worked in the house, ‘yard boys’ that worked in the yard, and then the boys that worked with the cows, and they were called ‘cow boys.’”

In the way the term cowboy was initially used, the first American cowboys were black Texan slaves. When white ranchers went off to fight in the Civil War, they depended on slaves to maintain their land and livestock. In doing so, these black cowboys developed skills such as horse breaking and cattle mustering, which proved to be invaluable to Texas’ cattle industry in the post-war era. During Reconstruction, former slaves known as Exodusters migrated along the Mississippi River. As some broke West, they also learned horse handling skills from Mexican vaqueros and cattle-raising Native Americans. “Right after the Civil War, being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to men of color who wanted to not serve as elevator operators or delivery boys or other similar occupations,” says William Loren Katz, a historian and the author of The Black West. Some notable black cowboys during this period include Bass Reeves (the real-life inspiration for The Lone Ranger), Bill Pickett (inventor of bulldogging), and Nat Love (a crack shot and cattle rancher whose life was a string of wild adventures).

“No picture of American history has been painted more white than the pioneer picture, the story of the frontier,” Katz says in an interview. “The West was part of the mythology of America; the cowboys, the narrative of the pioneer spirit represented the best of us. And if the black people came along, they came along at the end of a whip and in chains. That’s not the American tradition people wanted to remember.”

There are all types of cowboys today. “Concrete cowboys” in Compton and Philadelphia bring communities together through horse rescuing, horse riding, and after-school, equestrian activities for local youth. In Oakland, the Black Cowboy Association holds a parade every year to celebrate the contributions of black cowboys to the American West. Although black cowboys have been historically underrepresented in rodeos, they compete today at Cowboys of Color Rodeo, Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, Cowtown Rodeo, Southwestern Exposition, and Juneteenth Festival, among many other events. During last year’s nationwide protests against the murder of George Floyd, cowgirl Brianna Noble rode her tall, chestnut-colored horse, who is charmingly named Dapper Dan, down one of Oakland’s main thoroughfares. A cardboard sign hung on her horse’s hindquarters that read: “Black Lives Matter.” “I know that what makes headlines is breaking windows and people smashing things,” Noble said. “So I thought: ‘Let’s go out and give the media something to look at that is positive and change the narrative.’”

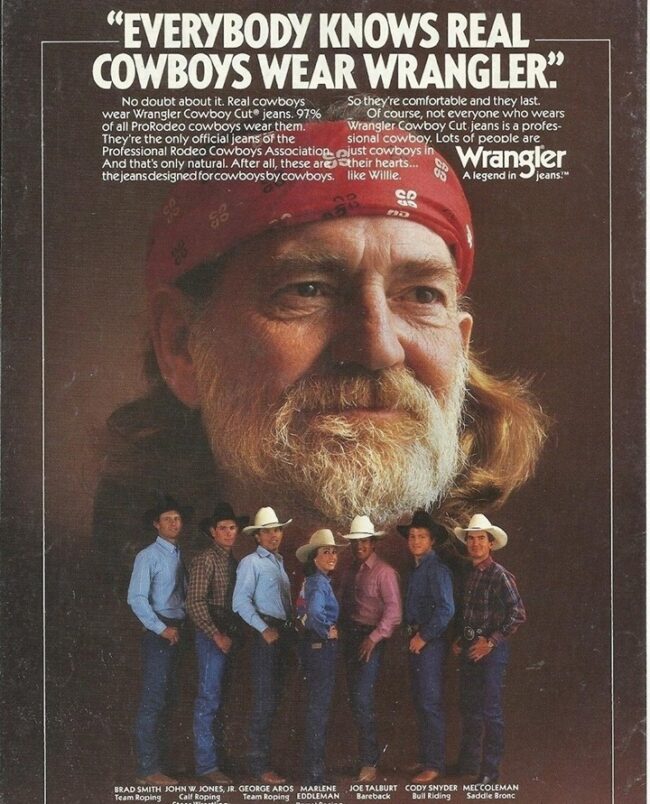

There are also Native American rodeos, complete with regional associations in two nations and at least two national finals. Donna Hoyt, who serves as the General Manager of the Indian National Finals Rodeo, the oldest organization of its kind, says such events are natural since horsemanship has deep roots in Native American culture. “They’ve inherited this lifestyle through their grandfathers and great grandfathers,” she tells me over the phone. “Today, they keep this Western heritage alive by participating in rodeos, Indian relay races, and other activities they’ve grown up doing.” Derrick Begay, a Navajo team-roping cowboy from a Native American reservation in Arizona, is one of the best rodeo competitors in recent times. Begay grew up with very little — a home with no electricity or running water, by his account — but was also raised in the saddle since his family had livestock. By the time he retired last year, he accomplished much. Begay is the first Navajo to make it to the National Finals Rodeo. He holds eight Wrangler National Finals Rodeo qualifications, six Indian National Finals Rodeo qualifications, a world champion title, and over $1.2 million in winnings. To people on his home reservation, Begay is a hero; to rodeo cowboys, he’s a legend.

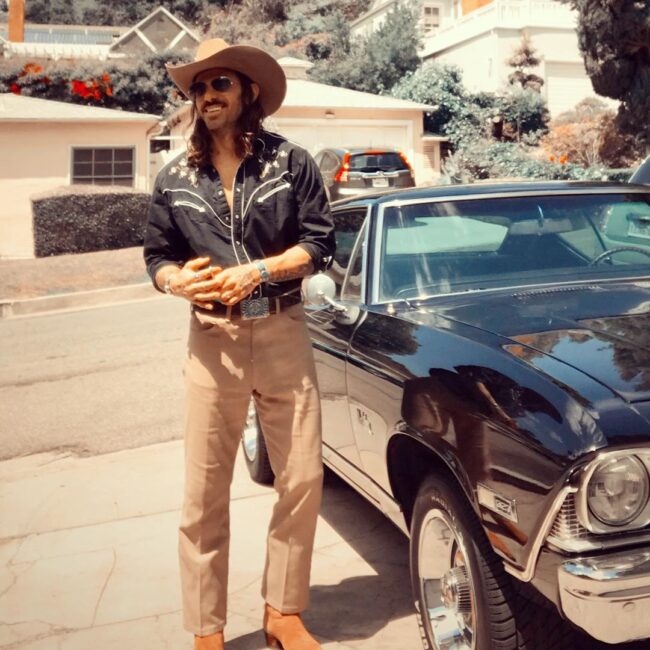

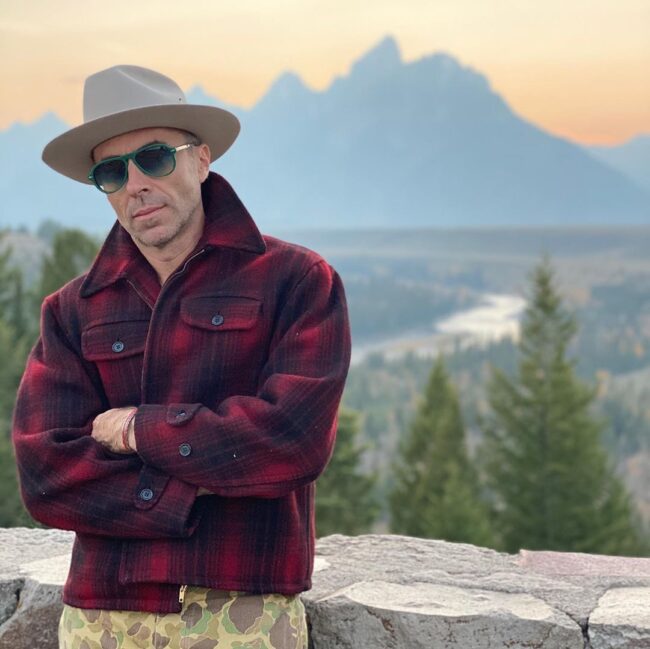

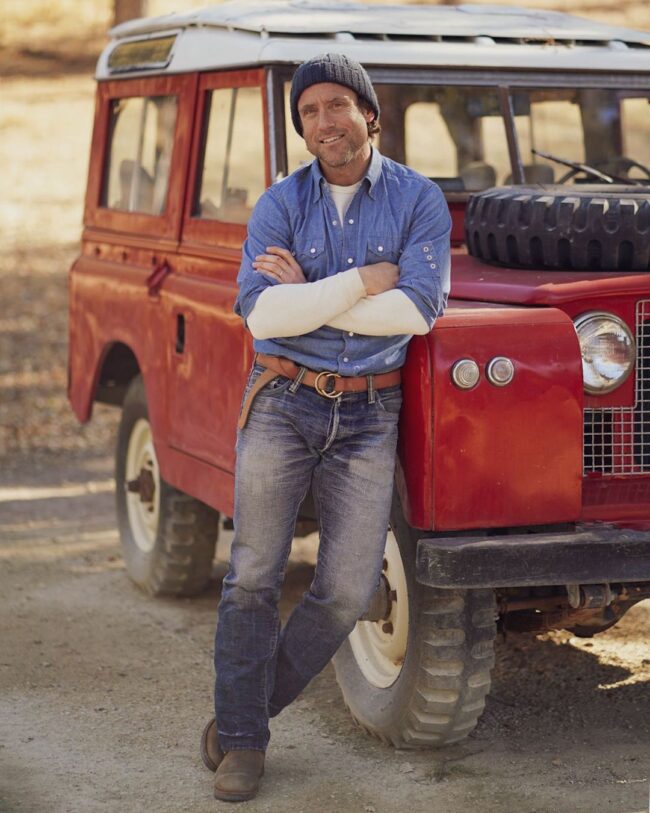

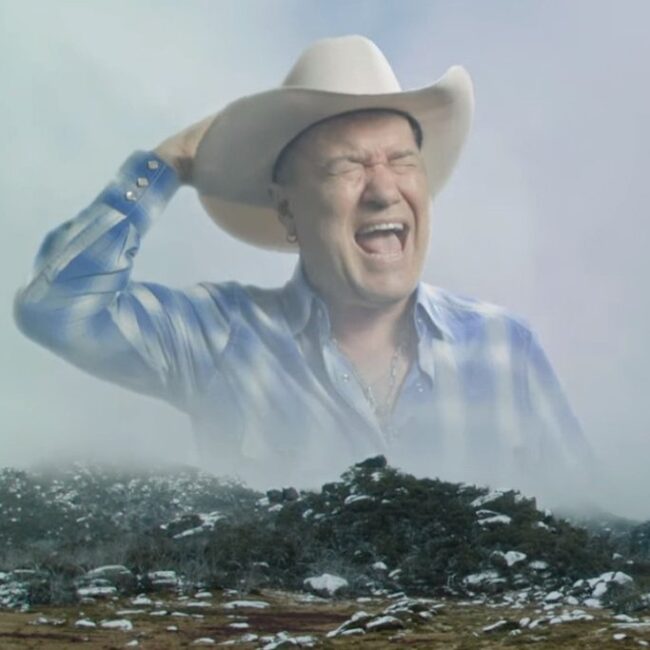

In the last year or so, Westernwear has come galloping back into popular culture, partly spurred on by the Yeehaw Agenda. As Daniel Penny recently noted in The Wall Street Journal, these clothes build on Hedi Slimane’s rebel rocker look and Emily Bode’s prairie patchwork creations. In the last five years, such items have slowly crept into my wardrobe, first with Wrangler’s $29 Western shirt, then an RRL ranch jacket, a vintage Lee 101J trucker, a stack of country-rock tees, and recently, my first pair of cowboy boots. I realize there’s something inauthentic about dressing like a cowboy in the city. The only thing I ride are trends; the only things I round up are eBay links. But I like these clothes for their rugged masculinity and enjoy seeing aesthetics pop up in unexpected places. North Carolina singer Boulevards mixes slow grooving funk and soul with a Westernwear uniform. Mitra Khayyam is an Iranian woman who grew up in the San Fernando Valley, but loves country music and puts her affection on vintage-inspired, country-rock tees. I like it when clothes work against social stereotypes.

I also think Westernwear speaks to something more profound. Although Turner’s thesis proved to be flawed, we’ll forever associate these clothes with American values such as self-reliance, resourcefulness, practicality, optimism, and rugged individualism. Even more than Ivy Style and the rebel rocker look of the post-war era, the cowboy aesthetic is about American identity. Plus, there’s something inherently appealing about clothes that are associated with the great outdoors. Modern life increasingly feels claustrophobic. Skyrocketing rents and overregulated housing markets in cities are pushing people into confined spaces; many of us work and play on the same tiny screens. In a recently published New York Times op-ed, Ian Leahy and Yaryna Serkez show how discriminatory practices have inadvertently made trees the new luxury. Across the United States, wealthy neighborhoods feature more greenery, while lower-income neighborhoods are surrounded by roads, parking lots, and concrete. I recently found myself browsing LandWatch, an online marketplace for open land, ranches, and farms, dreaming what it would be like to move to the countryside. William Butler Yeats captures this sentiment beautifully in his 1890 poem “Lake Isle of Innisfree:”

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

A BASIC GUIDE TO WESTERNWEAR

If you’re looking to explore Westernwear, here are some things that I’ve found to be useful as entry points. The resulting outfits can be anywhere on a sliding scale of yeehaw, going from full cowboy to rock-and-roll adjacent.

The Western Shirt

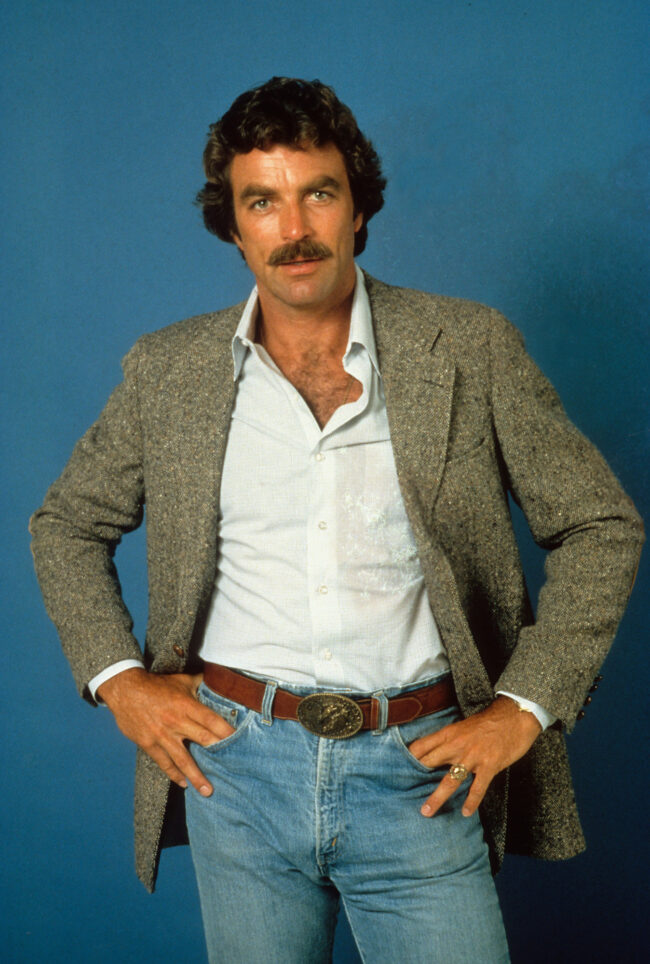

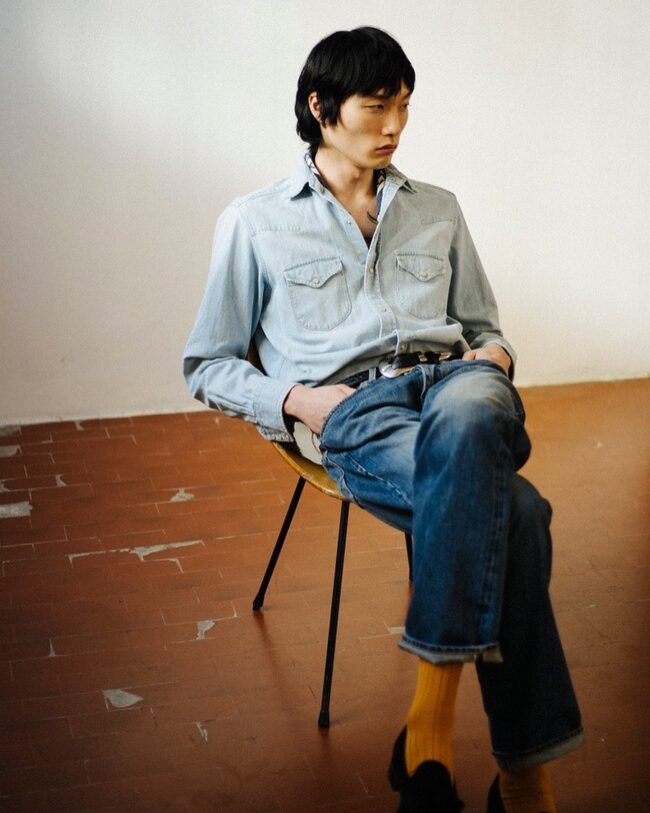

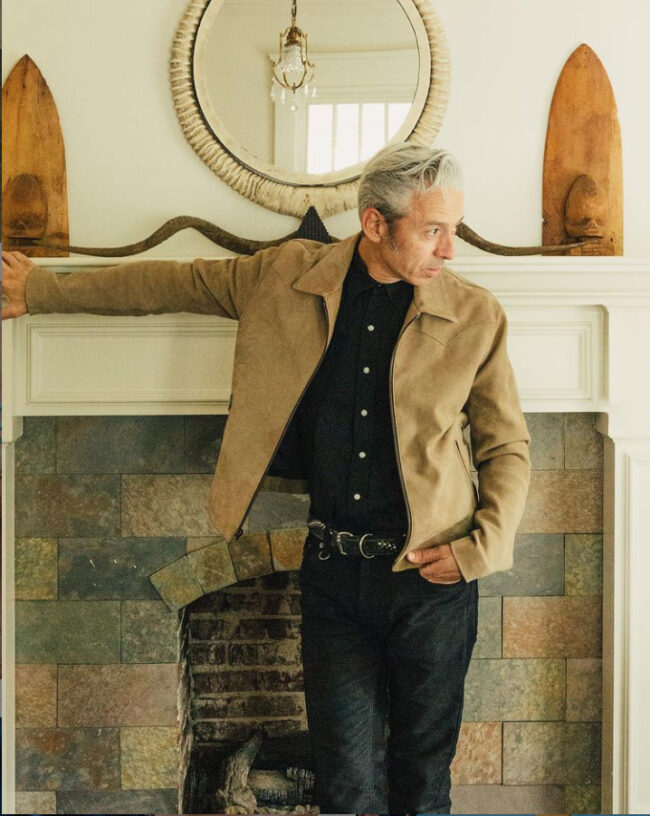

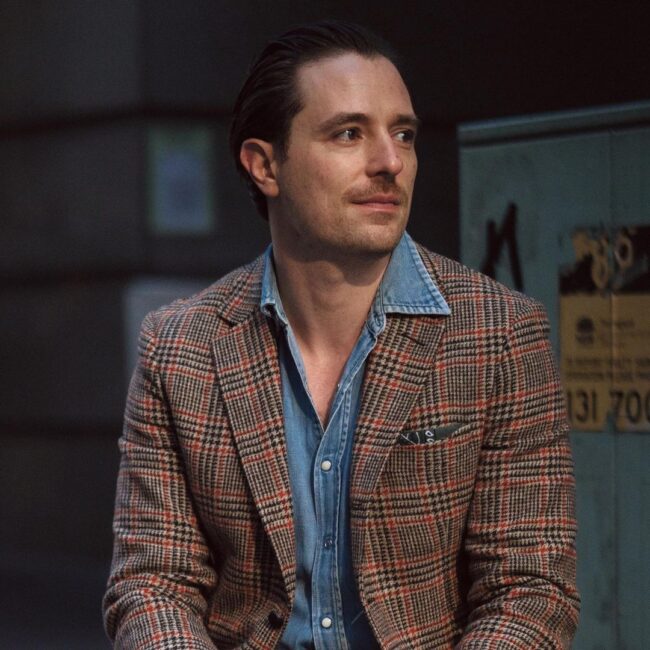

Western shirts pair well with almost any kind of workwear that you can imagine finding at Levi’s, including denim truckers, chore coats, and most leather jackets. At the same time, they can be easily worn with casual suits and sport coats, particularly those made from cotton or tweed. Giuseppe Santamaria, the talented photographer behind Men In This Town, snapped the photo above of a man wearing a washed denim, snap-button shirt with a tweed sport coat. I love the way John Goldberger wears this combo in a Hodinkee episode of Talking Watches (sooo good!). Peter Zottolo also pairs his black denim Bryceland’s shirt with everything from suede truckers to Donegal suits.

I have Western shirts from Wrangler (in washed denim), Kapital (raw denim), Iron Heart (thick flannel), Barbanera (micro corduroy), and Wythe (Tencel). The Wythe shirt drapes like silk and has such a beautiful, warm color; it almost makes you feel like Richard Gere in American Gigolo when you put it on. The teardrop-shaped pockets and collar are so perfectly designed, the shirt even works well on its own without outerwear. It’s one of my favorite purchases in the last year (I think the shirt works best in cream). You can also find good Western shirts from Bryceland’s, Tony Shirtmakers, Stevenson Overall Company, Indigofera, The Real McCoys, Freenote Cloth, Flat Head, RRL, Todd Snyder, and Taylor Stitch. For something custom-made, go with a shop with experience in this style, such as CEGO, Proper Cloth, Fort Lonesome, or Viapiana.

The Layered Henley

With a tailored outfit, you usually don’t want the top of a white undershirt peeking out from beneath your button-up. But this effect can look ruggedly masculine when done with a Western shirt. In the springtime, you can layer a solid-colored or graphic t-shirt (I like Imogene + Willie and Midnight Rider for new tees, and Moth Food and Afterlife for vintage). When it gets colder, thermals will keep you cozy.

I mostly like wearing henleys because they create a more interesting neckline. Mine are from Barena. They have extra-long sleeves, which I think look good with contemporary items such as Margiela’s five-zip. At the same time, the sleeves can be folded back when worn with a denim shirt. Alternatively, you can find quality henleys from Merz b. Schwanen, RRL, Homespun, Faherty, Save Khaki United, Pistol Lake, Stevenson Overall Company, Barbanera, and J. Crew. White works best as an undershirt color.

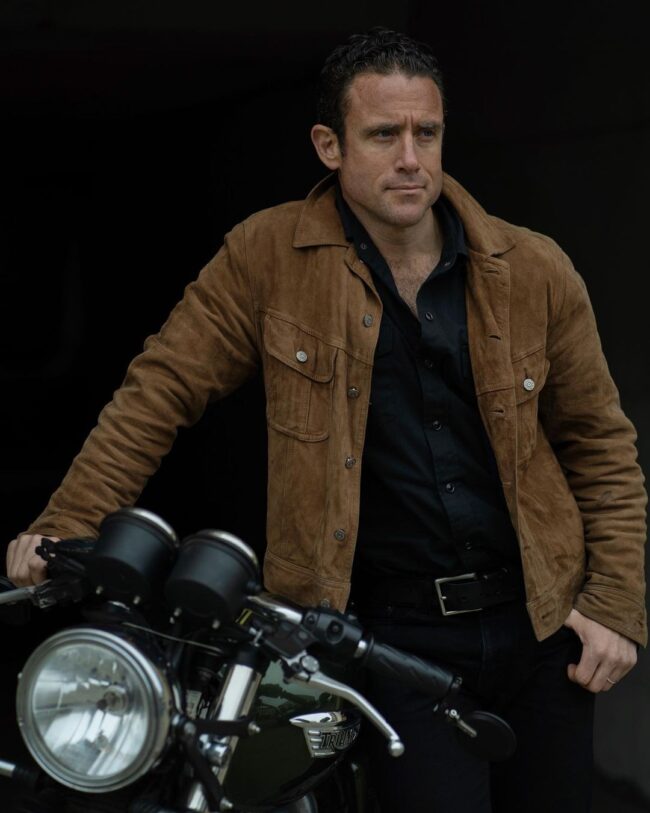

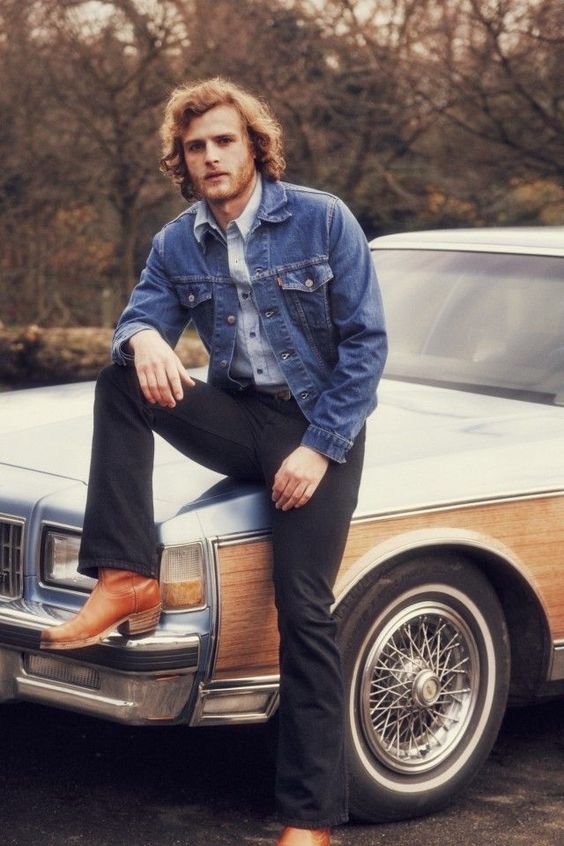

Western Outerwear Options

A denim trucker jacket is the tofu of outerwear — you can add it to anything and it will pick up the surrounding flavors. When worn with a pair of chinos and an oxford button-down shirt, it borders on prep. With fatigues and a chambray shirt, it almost feels like militaria. And when paired with jeans, flannels, and a pair of roper boots, it has echoes of Westernwear without going full yeehaw. In the colder months, you can even wear it as a mid-layer with roomier outerwear. (See Milad Abedi’s photo of Nathaniel Asseraf above, or the many photos of Alessandro Squarzi in this style). I like vintage Lee 101-J jackets best because they have dropped shoulder seams and a v-shaped silhouette, but the straight fit of Levi’s is also good (look for ones with the Big E). For brand new jackets, you can try Orslow, Levi’s Vintage Clothing, Iron Heart, 3sixteen, Chimala, Kapital, Wallace & Barnes, the Native American-owned brand Ginew, and anything from Self Edge.

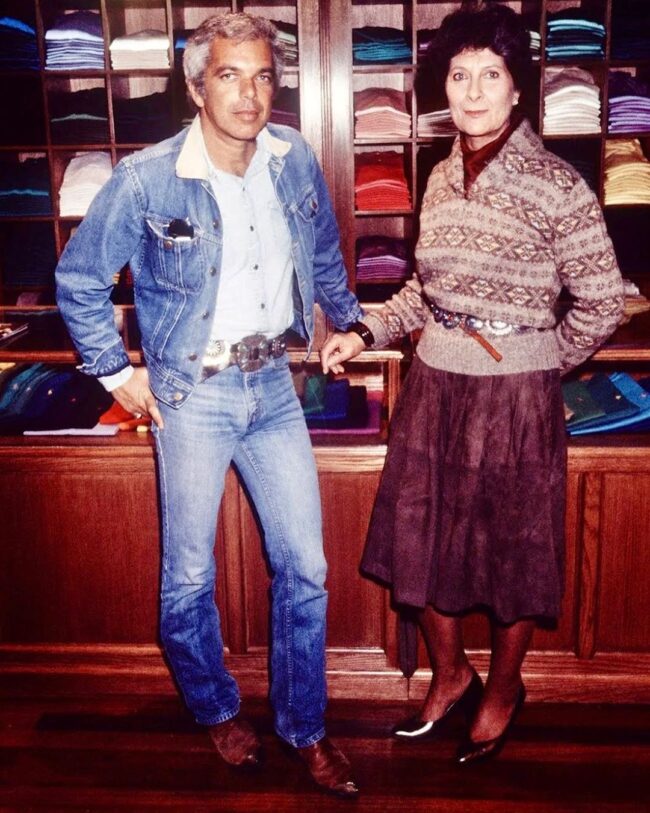

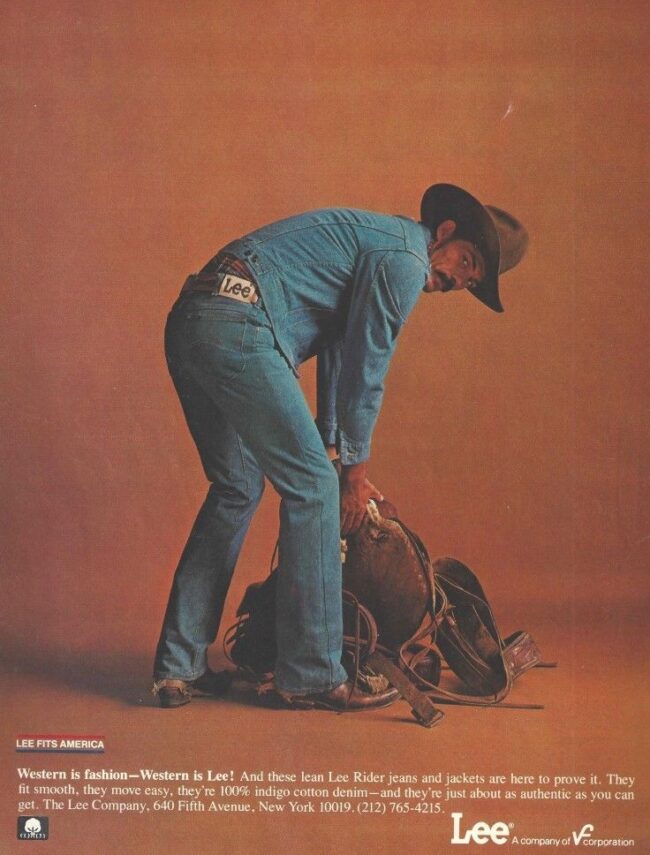

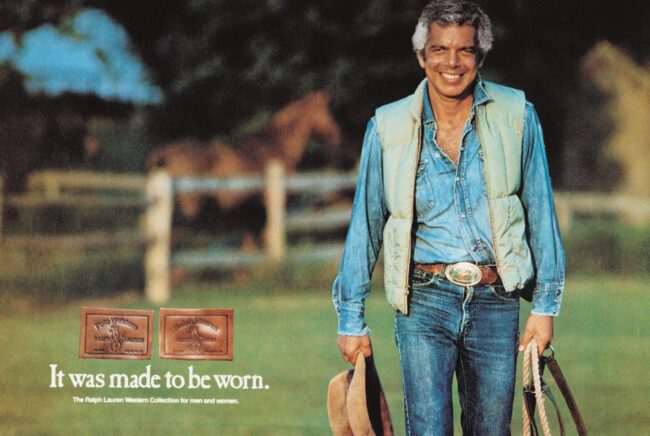

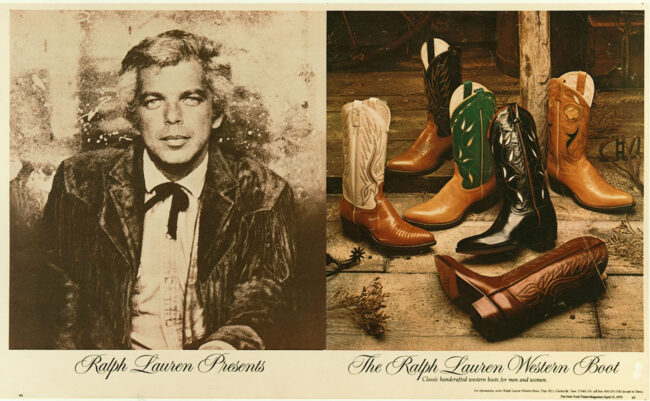

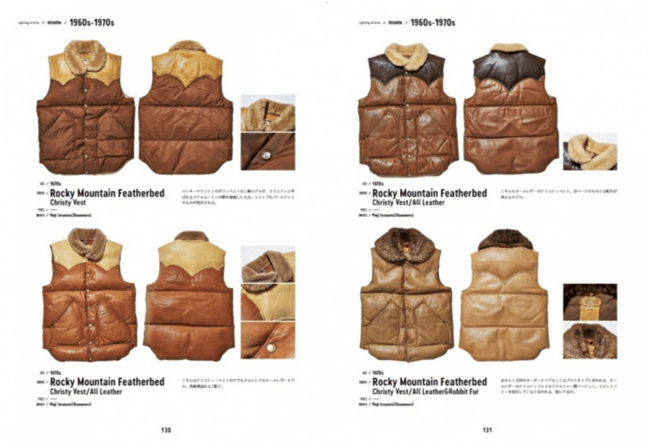

If you’re up for a splurge, the same style does exceptionally well in suede. You can find those from Barbanera, Officine Générale, Todd Snyder, The Real McCoys, and Levi’s Vintage Clothing. The custom leather jacket shop Atelier Savas offers the style as made-to-measure or bespoke (their blush blue suede looks especially nice). If No Man Walks Alone, a sponsor on this site, brings back their suede Valstar shearling trucker or Clint jacket this fall, both of those do well for this type of wardrobe. Margiela has an interesting Western-ish jacket this season. Additionally, you can browse eBay or Etsy for certain names: Rocky Mountain Featherbed for that Colorado ski-instructor look; vintage Hercules, a line that Sears and Roebuck made during the 1930s and ’40s; and the now-defunct Ralph Lauren Polo Country label. I like how former Abercrombie & Fitch designer Aaron Levine wears this duck canvas Polo Country work jacket. Second-hand shops such as Wooden Sleepers, Velour, Marrkt, Raggedy Threads, Moth Food, Chad Isham, and The Goody Vault are also full of unique treasures.

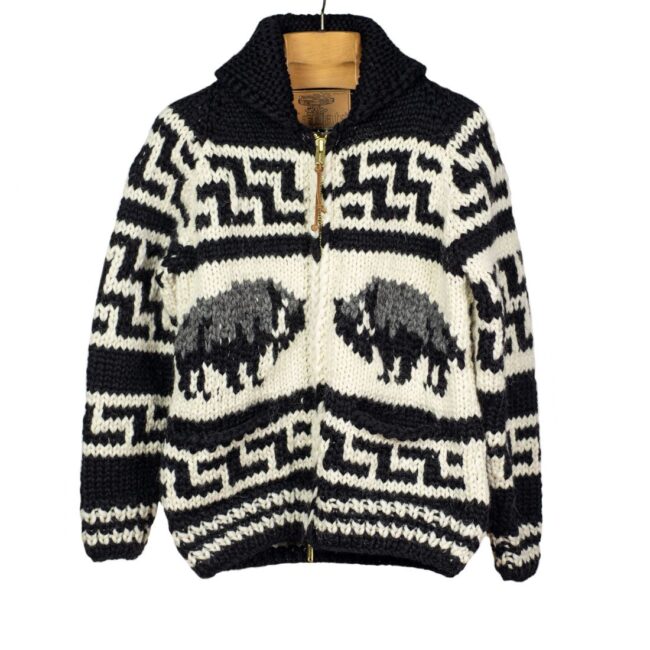

Sweatshirts and Chunky Cardigans

A black or heathered grey sweatshirt should take care of most situations, but a special mention should be given to cardigans. I mostly think of chunky, shawl collar cardigans as something you wear around the home or when entertaining guests during holiday parties. They look great with chinos or tailored trousers if you want to evoke a particular “classic menswear” look, but they’re not right for the rustic look of Westernwear. For that, you’ll want an RRL cardigan or a Cowichan. Those are hefty, thicker, and made from much more robust yarns. Just check out how amazing Sean Robinson looks in his RRL cardigan, chambray shirt, and olive jeans. No Man Walks Alone carries some handsome Cowichans from Kanata. Canadian Sweater Company is another good source. You can also find second-hand Cowichans on eBay. The ones made by home-knitters can sometimes fit wonky, but that’s part of the charm.

Jeans and Tailored Trousers

At this point, you probably already have a pair of slim-straight, raw denim jeans. So long as they fit comfortably over pull-on boots, I think these work well in blue, black, and the right shade of tan. Such jeans are the backbone of a Westernwear wardrobe — something you can wear with flannel or denim shirts, nearly any kind of jacket, and most chunky cardigans. If you’re worried about the denim-on-denim look, just switch up the colors (so tan jeans with a blue trucker, or a tan canvas ranch jacket with blue jeans). These days, I mostly wear slim-straight jeans from RRL.

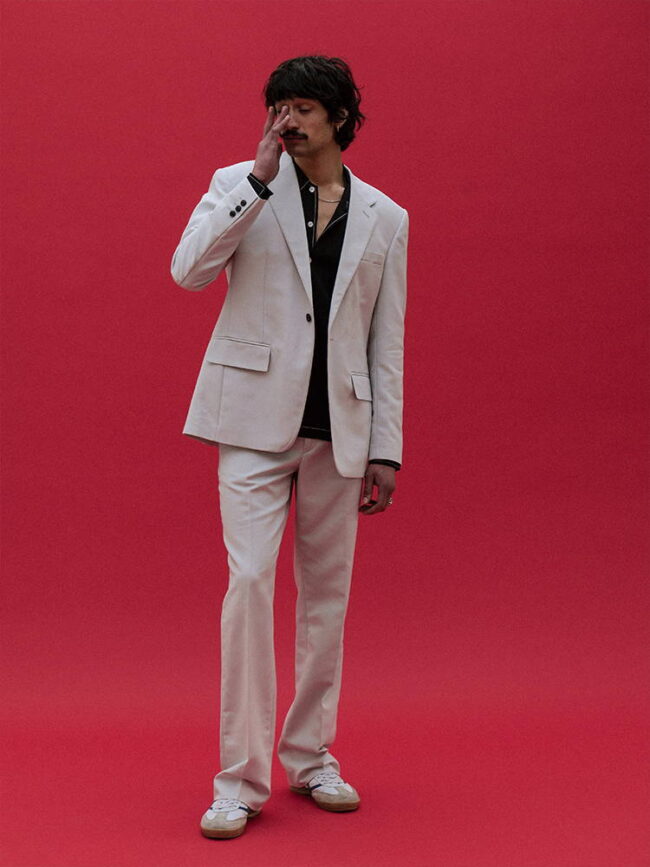

Tailored trousers can work, but it helps to have something made from rustic materials such as cavalry twill, Bedford cord, or whipcord, rather than slick worsteds or even woolen flannel. French-American artist Mark Maggiori often wears tailored trousers with retro-styled shirts and Western belts. Additionally, you can try “dress jeans,” which are made from a thick polyester but have the texture of twill. They evoke a 1970s Westernwear vibe in the best of ways. I like Wrangler’s Wranchers, a mid-rise, sta-prest, bootcut model that looks good in colors such as birch, brown, and black (size up two in the waist and take your regular inseam). People on Reddit and StyleForum have been posting outstanding fit pics with this model.

The Western Boot

Boots are the heart and soul of a Westernwear outfit. For the most part, you can wear the same Red Wings and Wolverines that are kicking around your closet. However, a good pair of Western boots can really bring this look into its own. There are two main types: ropers and cowboy boots. Ropers have a regular heel and plain toe, while cowboy boots have an elevated heel that’s meant to sit securely in a stirrup and toe stitching for decoration. Choose ropers if you suspect you’ll want to wear these with a broader range of non-Western workwear outfits. They work in any outfit where you’d wear work boots. Cowboy boots, on the other hand, are more distinctive and thus limiting. They look great with Westernwear items such as trucker jackets, but less so with workwear from brands such as Nigel Cabourn or Engineered Garments.

The world of Western boots is wide and diverse, with companies making things from unidentifiable petroleum products and high-end leathers. In recent years, newcomers such as Ranch Road, Chisos, and Tecovas are challenging established names such as Lucchese and Rios of Mercedes. There are even bespoke cowboy boots. Lee Miller of Texas Traditions trained under the famous Charlie Dunn, a legendary bootmaker whose work is immortalized through song. Today, Miller is passing on that knowledge along. Graham Ebner, an apprentice bootmaker at Texas Traditions, is now taking independent orders, but you have to fly to Austin, Texas to get measured and fitted.

In the ready-to-wear market, I’m impressed by JB Hill and Rios of Mercedes. Both companies produce their boots in the US using traditional methods and offer a wide range of tastefully conservative and wild styles. Actor CJ Cook has a YouTube channel where he reviews Red Wings and cowboy boots, including several pairs of Rios (he even has his own boot). Heritage Boot Company is priced like Crockett & Jones — somewhere in the mid-range of this market — and offers unabashed, attractive styles. On a budget, I recommend Tecovas, the Meermin of Western boot companies. They’re made in Mexico using full-grain leather and traditional Western methods, including lemonwood pegging and 3/4th Goodyear welting. Earlier this year, I picked up two of their styles — The Stockton in clay and The Cartwright in bourbon — and love them. My only quibble is that, while the Cartwright is made from full-grain leather, it doesn’t achieve that scuffed patina that I think looks so charming in this style. The boots get wrinkly, but not scuffed. At $250, however, you can’t do better.

For something less yeehaw, Atelier Savas’ Legend Boots perfectly skirt the line of Westernwear. Savas designer and founder Savannah Yarborough describes these boots as “tasteful rock and roll.” For years, she designed menswear collections for Billy Reid, helping create the company’s Southern “dressy-casual whiskey-soaked style.” She famously once took home one of the company’s leather jackets and experimentally wore it while soaking in a bathtub, like a leather jacket version of guys wearing shrink-to-fit jeans. That ended up spurring her on to create her own leather jacket company, Savas, where she makes fully customizable bespoke and made-to-measure jackets.

These boots feel like an ode to that experiment. Like Carol Christian Poell’s famous tornado boots, the Legend is vat-dyed and -soaked. This process gives the boots a uniquely beautiful, uneven color and texture. I was unsure of the two-point rivets at first, but found the detail subtle and tasteful (I’ve even come to like them). While trying the black ones with slim black jeans and a trucker jacket, I was surprised by how they feel very rock and roll, which only underscores the flexibility of a “Western” look. Savas and Savannah’s personal Instagrams are quite inspiring for this aesthetic.

The Final Touch

Western belts can make all the difference here between a boring outfit and something more distinctive. Leatherworkers such as Don Gonzales, Colton Cunningham, and Lone Tree Leather Works offer beautifully tooled belts, although you may need to find a suitable buckle on eBay. Don’t Mourn Organize’s Clint stitch belt is modeled after something Clint Eastwood wore as The Man With No Name (warning: that double horsehide belt is very thick). Foothills California also sells vintage belt straps fitted with authentic Native American buckles (more about them in a later post).

Tapered belts are arguably your most stylish option. These belts are typically 1.25 or 1.5 inches wide at the back and gently taper towards 0.75 inches at the front. Companies such as Adriano Meneghetti, Silver Ostrich, Fortela, and Monitaly offer modern interpretations of this style. Lemaire makes minimalist ranger belts, a cousin of the tapered belt. I think the best option here is to go authentic. You can find sterling silver buckles made in the American Southwest by Native American silversmiths on eBay for about $150. Just search for terms such as “ranger belt buckle,” “Native American belt buckle,” or “Navajo Belt buckle.” Once you’ve secured a buckle, you can send it to Ken at Custom Leather Belts to have it fitted on a leather strap. My tapered belt is pictured above, attached to my tan RRL jeans. The buckle is from Navajo silversmith Anderson Parkett. Pro tip: many eBay sellers are eager to negotiate. If you add a buckle to your wishlist, you’ll often get an offer for a lower price within twenty-four hours. Bastion42 on eBay has hundreds of attractive options.

For fun, I created a soundtrack for this post. You can click play on the Spotify playlist and scroll through the photos below.