Shortly after the loud roar of New Year’s celebrations quieted in 1955, Ernst Friedrich Schumacher flew into New York City on his way to Rangoon. He had been to the United States before. In the 1930s, he attended Columbia University as a student of economics and even took a year-long post as a lecturer at Columbia’s School of Banking. But if the city’s bright lights spellbound him as a young man, he saw them differently now. At the time, he had just been appointed as an economic advisor to the newly independent Burma, and was required to attend a series of United Nations briefings before his trip. Each day, when he came out of his Midtown Manhattan hotel, he felt a vague sense of disgust for the crisscrossing roads and oversized vehicles he saw everywhere. “One gets the impression that the primary preoccupation of the American people is with motor cars,” he wrote to his wife back home, “you see nothing but cars everywhere you look, cars moving, cars shopping, cars parking, cars for sale, cars required and unrequired, all enormous and ugly.” Schumacher, who had dedicated his life to promoting growth, started to question his role as an economist.

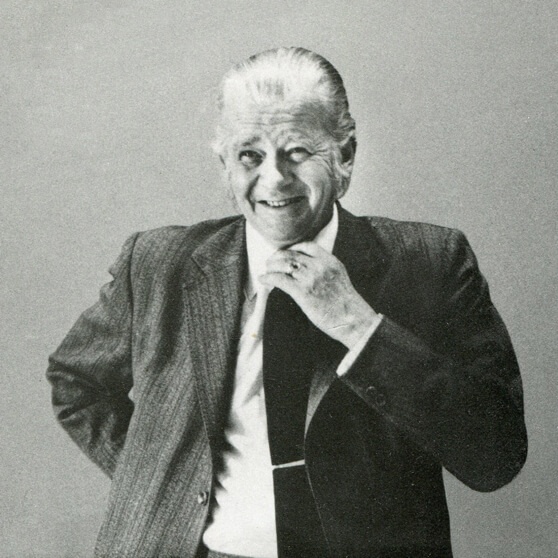

Born in Bonn, Germany in 1911, as the second son of a political economy professor, Schumacher grew up in the ivory tower of academia. He attended the best schools — The London School of Economics, Oxford, Cambridge, and Columbia University — and studied under some of the great British intellectuals of his day, including John Maynard Keynes, Arthur Cecil Pigou, and Dennis Robertson. Upon finishing his studies, he returned to Germany in April 1934. Two months later, Hitler, then Chancellor, purged his party of disloyalists and, shortly after, declared himself Führer of the German people. Appalled by the Nazis, Schumacher fled to London the following year. When the war broke out at the dawn of September 1939, Schumacher and his wife remained separated from their German family for the duration of the conflict.

Life for Schumacher was not easy during the war, even as he took refuge in Britain. At the outset, he was labeled as an “enemy alien” and interred at the Prees Heath camp in the Shropshire countryside. After several months, he was given an early release by the government, thanks partly to his connections to a network of influential British figures. Schumacher then moved to Eydon Hall, an isolated Northamptonshire estate located not more than twenty-five miles from where John Lobb and Crockett & Jones produce their shoes today. While there, he toiled in the fields, repaired fences, and brought in the harvest by day, and then wrote papers about international economics by night. Always a voracious reader, Schumacher also consumed a mountain of books. He pored over the writings of Marx, Engels, and Lenin, essays by J. B. S. Haldane, J. D. Bernal’s The Social Function of Science, Seebohm Rowntree’s Poverty and Progress, and C. H. Waddington’s The Scientific Attitude. By the end of his time at Eydon Hall, Schumacher, an erstwhile liberal, became a cocksure socialist and strident atheist. He would later recall his time at the farm as his “real education.”

After the war, Schumacher became a prime mover in Europe’s postwar reconstruction. He got a job as a researcher at Oxford, thanks in part to his friend and mentor, Keynes, who gave him a personal recommendation. Working alongside William Beveridge, Schumacher helped shape Britain’s postwar welfare state. As an economic advisor to, and later Chief Statistician for, Britain’s Control Commission, he was part of the Allied team tasked with Germany’s reconstruction. Now a British subject, Schumacher returned to Germany for the first time in ten years. As he walked the streets of Berlin, he was dumbstruck by the post-war wreckage he saw everywhere. “You cannot believe it. No person can imagine such a thing,” he wrote to his wife. “Dante couldn’t describe what you see there. A desert.” When Schumacher left Germany again in 1949, he was all too glad to get away from the bureaucratic red tape and infighting between the Allies. Upon returning to Britain, he accepted an appointment as an economic advisor to the British National Coal Board. He and his family then relocated to a large countryside home just outside of London, presumably so Schumacher could settle into his new, quiet life as a low-profile energy economist.

Up until he was about 45 years old, Schumacher was a confident modernist and materialist. Like all conventional economists, he believed in the Western models for growth, which are built upon certain assumptions about the inherent “goodness” of technological development and material wealth. But something changed for him in the mid-1950s. Perhaps influenced by the long separation from his family during the war, his time on the Northamptonshire farm, or the destruction he saw in post-war Germany, Schumacher became increasingly interested in issues regarding spirituality and belonging. This came to a head for him in January 1955, when he arrived at the Kanbawza hotel in Rangoon as a UN advisor, tasked with helping the Burmese government grow the nation’s economy. “I came to Burma a thirsty wanderer,” he later wrote, “and there I found living water.”

Burma left an indelible impression on Schumacher. He was endlessly impressed by the “charm and cheer” of the Burmese people, their connections with their community, and their work-life balance. In a letter to his wife, Schumacher wrote about the wild birds that flew in and out of his hotel room, unafraid as humans never hurt them. “There is an innocence here which I had never seen before — the exact opposite of what disgusted me in New York,” he wrote. “Even some of the Americans here say: ‘How can we help them when they are much happier and much nicer than we are ourselves?’” The more Schumacher opened himself up to Burma, the more he saw Western encroachment as a threat. He became increasingly worried that the economic prescriptions for growth — which include rapid industrialization and urbanization — would steamroll over Burmese culture and spiritual traditions. He feared that “development” would push the Burmese people into becoming a rootless proletariat, as they wander from city to city, looking for factory jobs. “I think there really is some work for me here, but it may be negative rather than positive, persuading them not to do various things rather than telling them what to do. Because on the positive side they need no advice: as long as they don’t fall for this or that piece of nonsense from the West, they will be quite alright following their own better nature.”

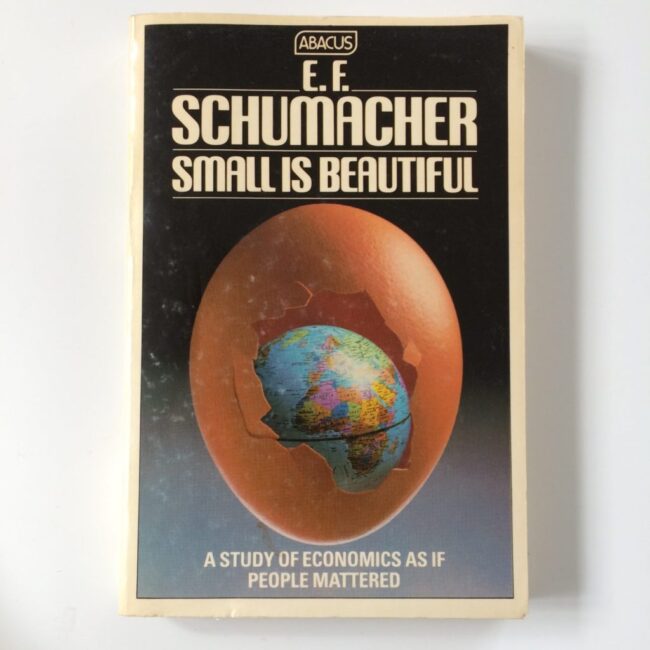

Schumacher later expressed his heterodox views in a series of articles published at The Observer, edited by his college friend David Astor, and later, as a fleshed-out book titled Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered. First published in 1973, Small is Beautiful predated many of the dominant political concerns today: the concerns about workers’ rights and automation, the skepticism of big institutions, and the interest in renewable energy and environmental sustainability. In his book, Schumacher warned that a globalized capitalist system dependent on a voracious consumption of finite natural resources would eventually threaten civilization and life itself. He attacked the prevailing faith that “bigger is better” in driving efficiency and prosperity, and explored the idea of “enoughness.” Schumacher wanted to bring capitalism back to a human scale — on a level that would put our economy back in touch with our needs, relationships, and values — even if it meant that many of us would be less materially wealthy. “Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent,” he wrote. “It takes a touch of genius — and a lot of courage — to move in the opposite direction.”

Small is Beautiful is full of pithy soundbites: “That soul-destroying, meaningless, mechanical, monotonous, moronic work is an insult to human nature;” “[W]here is the rich society that says: ‘Halt! We have enough’?;” “[S]ince consumption is merely a means to human well-being, the aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption.” Perhaps most famously, and captured in the title of his book, Schumacher believed that we should organize society along “lots and lots of small, autonomous units.” When the book was first released in 1973, it was quickly swept up by the decade’s counter-cultural zeitgeist. At the time, many were already troubled by the ecological impact of wasteful consumption, the alienation common in modern society, and the overspecialization that made workers feel like appendages to a machine. Student radicals, social critics, and even some heads of state turned to Schumacher for his vision of a better, more holistic society. His views can be neatly summarized by this quiet sentence in another one of his books, A Guide for the Perplexed: “Our task is to look at the world and see it whole.”

Sadly, Schumacher only enjoyed a few short years of recognition for his 1973 bestseller. Shortly after it was released, he went on a non-stop world tour to give lectures in front of attentive audiences. Some of these audiences numbered in the tens of thousands. But in 1977, while on a train to Zurich to give another lecture, he dropped dead from a heart attack. Nearly twenty years later, The Times Literary Supplement included Small is Beautiful in their list of the 100 most influential books published since the war.

A few months ago, while I was interviewing Déborah Neuberg, I heard echoes of Schumacher’s ideas over the phone. Neuberg is the founder and Creative Director of De Bonne Facture (French for “of good make,” a name that’s as uncomplicated as the label’s clothes). Neuberg describes herself as a feminist and speaks passionately about workers’ rights and environmentalism. Yet, she also recognizes the tension between her values and working in an industry synonymous with labor abuse and wasteful consumption. “As a designer, I believe in taking a more conscious approach to commerce,” she told me over the phone. “That involves drawing from my spiritual tradition and heritage. Commerce doesn’t have to be exploitative. I want to honor it as something that’s an exchange of goods and culture, at a fair price, while respecting each step that goes into making quality goods.”

Founded in 2013, De Bonne Facture very much embodies the sort of human-scale capitalism that Schumacher championed. To be sure, there’s something inherently slower and more sustainable about operating as a small clothing brand. Without the pressures of corporate shareholders or needing to meet quarterly earnings targets, designers aren’t forced to churn out four-plus collections per year — spring/summer, fall/winter, pre-fall, resort (sometimes called cruise), and couture. Instead, small labels typically stick to the usual two-season calendar and often carry designs over from season to season, just in different fabrics. Consequently, consumers don’t always feel like they need to rebuild their wardrobe. The jackets I bought from Stoffa and Nigel Cabourn nearly seven years ago are still in their collection today. By contrast, high-end designer pieces from that era are now sometimes described as “archival.”

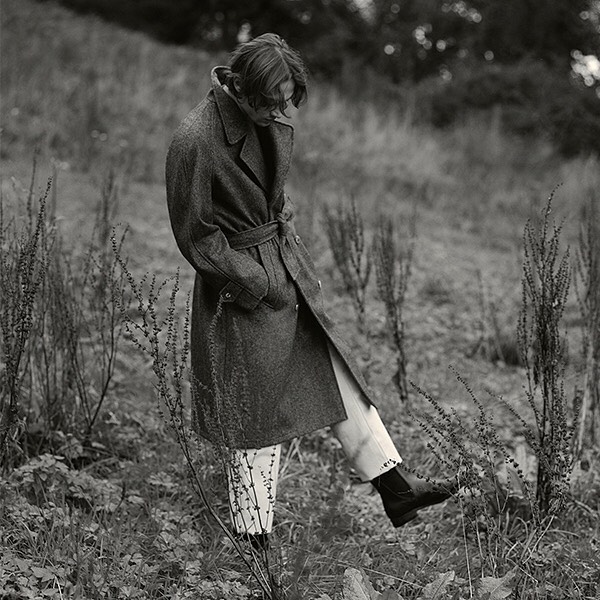

One of De Bonne Facture’s most popular perennials is a double-breasted overcoat made with raglan sleeves, a belted waist, and an Ulster collar. Charmingly named the “Grandad Coat,” Neuberg says the style is modeled after something someone brought into her showroom. “This guy came into the showroom once for a private sale, and he brought me his grandad’s coat,” she explains. “His grandad was a businessman in Brittany in the 1930s, and this guy wanted to exchange this coat for some De Bonne Facture clothes. I was like, ‘No, please don’t do that. You should keep your grandad’s coat.’ But he really, really insisted. So I told him, ‘You know what? I think the coat is really beautiful, so we’ll use it as an inspiration.” The coat has since become one of the company’s bestsellers. It has just the right touch of old-school sensibility with its generous proportions, but has also been updated in subtle ways, so it doesn’t look dated and dusty. I’m continually impressed by the effortless cool that some men exude by simply throwing a “Grandad coat” on top of whatever they’re wearing.

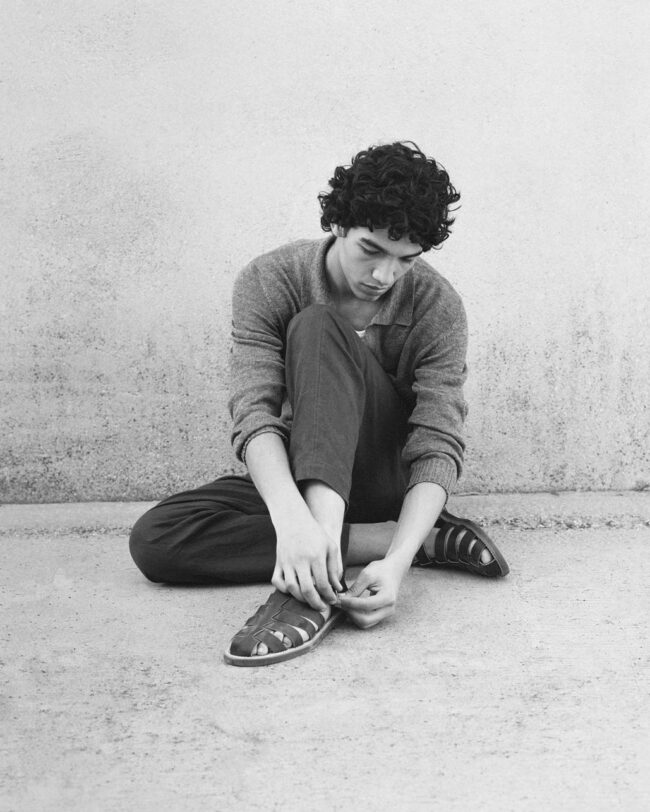

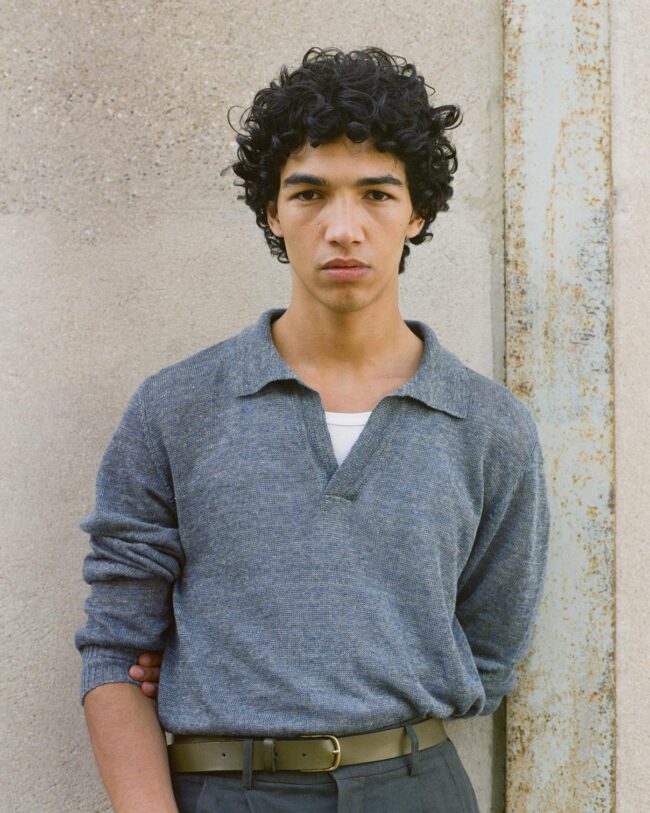

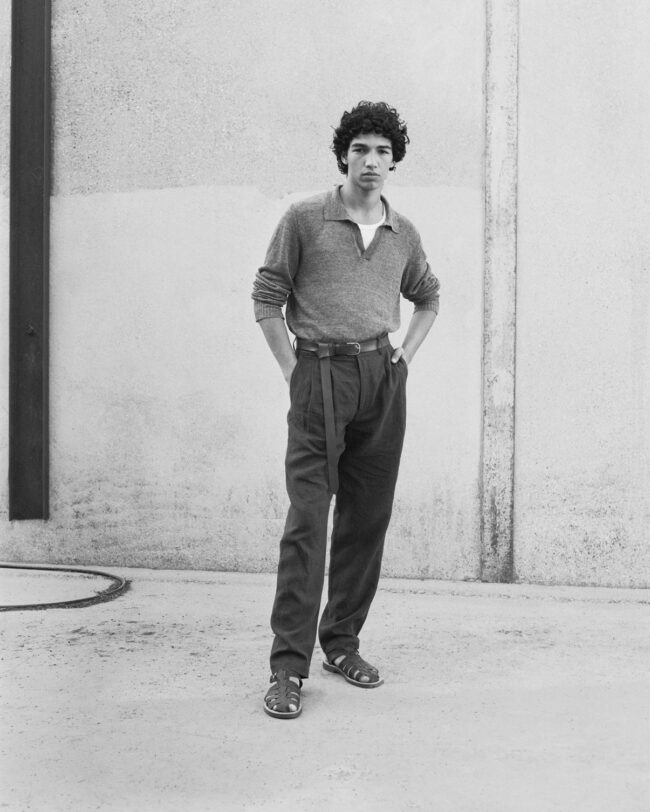

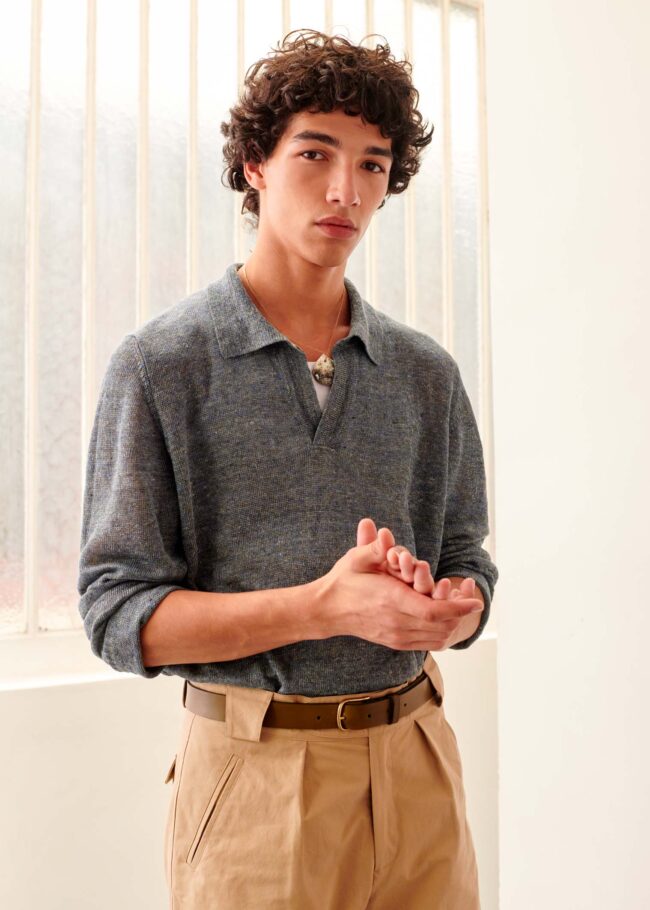

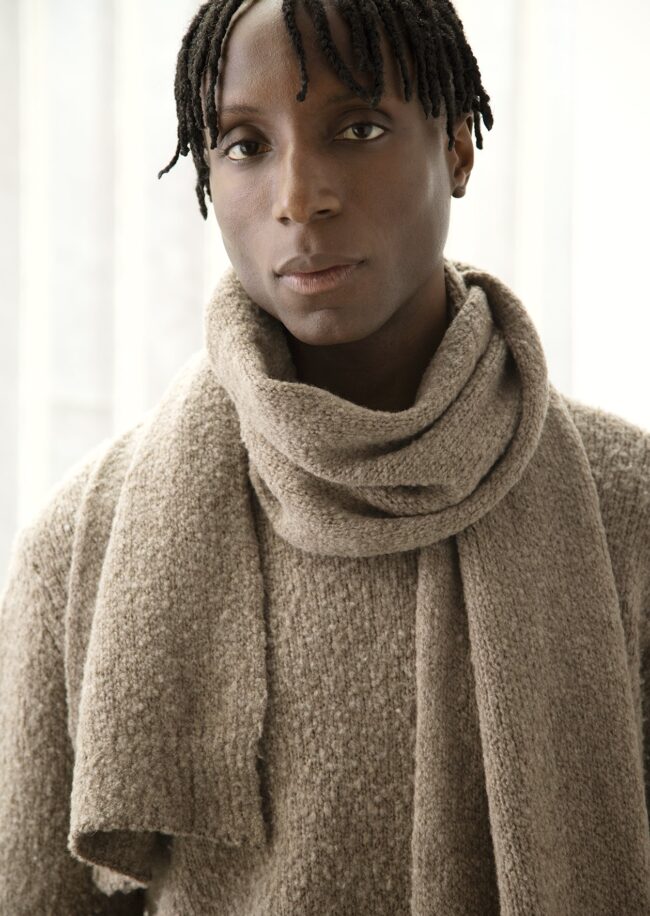

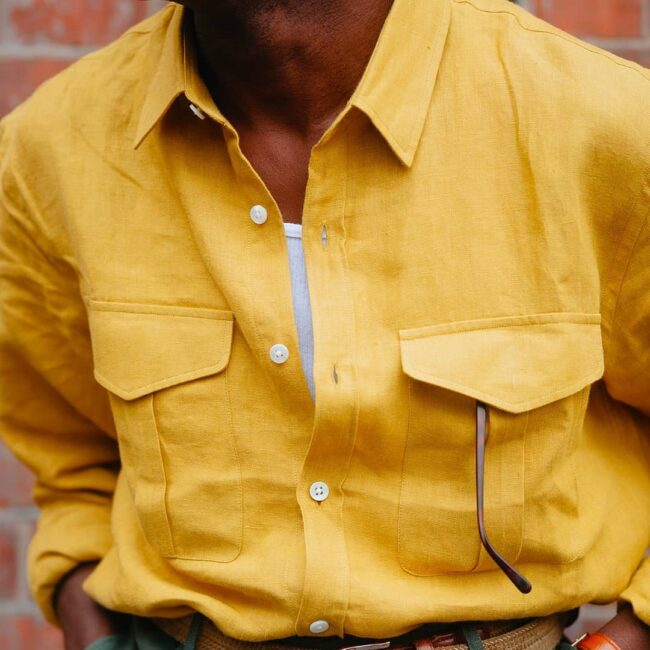

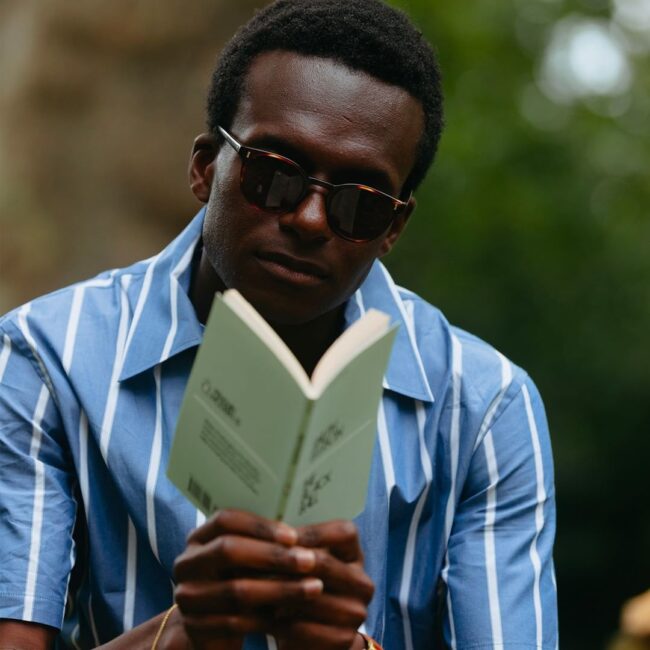

De Bonne Facture has other perennials, as well as themes that carry over from collection to collection. The company specializes in simple, serene clothes with a strong focus on quality materials. The designs are commonly rooted in workwear and utility, but they’re tweaked in ways that make them feel sophisticated and elegant. Each collection has some version of a work jacket, such as this season’s organic cotton “architect jacket” and washed wool-linen “painter jacket,” which look like refined versions of the iconic French chore coat. Their clean-fitting, straight-legged trousers are commonly finished with elasticated “easy” waistbands and shy pleats, which allow them to straddle that fine line between tailoring and leisurewear. Their shoes, which are made in collaboration with La Botte Gardiane, are again elegant riffs on workwear styles — a handsome woven leather “fisherman” sandal and an elegant roper boot. De Bonne Facture’s clothes look like something an imaginary artist or writer might wear in some idyllic pastoral home. Indeed, some of the clothes don’t look too different from the ribbed cardigans, mock neck pullovers, and tailored trousers Schumacher enjoyed wearing in his study.

More than just being a small brand with some “permanent” pieces, De Bonne Facture is Schumacherian in other ways. Remember, Small is Beautiful is not an anti-capitalist screed. Instead, it was meant to be a clarion call to scale back capitalism so that the market could be in better touch with our human needs, values, and relationships. Schumacher worried that mass-marketization and industrial production were pushing us towards an ecological disaster, and that overdeveloped technology was stripping the dignity from work. He wanted us to move towards something smaller and more sustainable so that people could lead happier, more autonomous lives.

De Bonne Facture shares many of those same values. As someone concerned with the environment, Neuberg tries to source organic cotton, undyed wool, and recycled materials when she can. She also tries to use small-scale, family-owned factories that are specialized in a specific trade, ideally ones that are rooted in a regional tradition. For example, in the southwestern part of France, there’s a factory that specializes in producing leather garments since the region has a rich tradition in sheepherding. “I like stories like that,” she says. “You can’t always have that, but I try to find those types of makers.” In using those factories, Neuberg is helping to keep those craft traditions alive.

All of these workshops are plainly listed on De Bonne Facture’s website, so that consumers can clearly trace how things were produced. Knits are made in Normandy by Tricoterie du Val de Saire; shirts are sewn in Arcos de Valdevez by Atelier Afonso; and workwear is constructed in Paris by Hervier Productions. When I asked Neuberg if she’s worried that this might help her competitors — after all, fashion is an industry known for copying — she almost seemed confused by the question. “When I started De Bonne Facture, I had this idea that things should be well made, and I was worried that many of these regions were already losing their craftsmanship and factories,” she explained. “So I wanted to build a label that was actually connected to the value of choosing certain makers and honoring them. Sometimes work gets outsourced because people don’t know that these amazing factories exist. I don’t see a problem if another brand goes to these factories and works with them. Why would that be a problem?”

Neuberg also sees the process of design as inseparable from manufacturing when making quality goods. “I wish more clothing designers thought of clothing as furniture or household appliances,” she says, “rather than fashion. When you design a product for the home, you have to think about how something will last for a very long time. It may be in someone’s home for ten, fifteen, or even fifty years. When it comes to fashion design, some people are designing things to only last six months. After that, people forget about the item and how it was made. I wish people thought about designing clothing more like how we think of designing furniture. That’s what De Bonne Facture means — it’s a French expression to describe a work of quality, whether that’s literature, a poem, a piece of furniture, or a piece of clothing.”

There’s a hint in Neuberg’s explanation that suggests maybe consumers should also shop for clothes in the way they shop for furniture — and perhaps the world would be better off if we thought in these longer timelines. “In any piece of clothing, a large portion of the garment’s ecological impact comes from how the fabric was produced, which is why we try to source sustainable materials,” she says. “At the same time, if we don’t think about how we design clothes, a garment’s design can also become obsolete too quickly. The third dimension is consumption. Even if you make a thoughtful design from sustainable materials, someone can come in and buy fifteen items, just going down your line in alphabetical order.” To help offset this, Neuberg tries to build in a sort of slow tempo, self-reflective theme in many of her online editorials.

I absolutely adore the “Patina” section on her website, which is a gentle reminder that we should enjoy the things we already own. In this section, Neuberg and her team interview guests about the oldest things in their closets. Such items range from the high-end designer to the common. Greg Lellouche of No Man Walks Alone talks about the Stephan Schneider coat he wore when he proposed to his now-wife. Marc Beauge of L’étiquette has a pair of ten-year-old Clarks desert boots that look just as admirable as a well-worn pair of Aldens. Lulu Graham, the author of Outfit Dissecting, shows off her grandfather’s hunting coat from the 1930s. Geoffrey Justeau’s 22-year-old Levi’s trucker jacket is cooler than any Japanese repro you’ve seen. Deeply personal memories are embedded into each garment, sometimes memories stretching across generations. Neuberg’s oldest garment is a shearling-collared, 1970s flight jacket that she inherited from her father, a pilot. She wore the jacket in middle school, and it was the inspiration for the pilot jacket design in her line.

During our conversation, Neuberg mentioned that she had seen a documentary on mulesing, a controversial husbandry procedure where farmers will cut a crescent-shaped piece of skin from a lamb’s buttocks, often without the use of anesthetics. The procedure is done to prevent maggot infestation (flystrike), but critics claim it’s unnecessarily cruel given the more humane alternatives, including specialized diets and spray washing. Shortly after watching the documentary, Neuberg did her own research and was so bothered by what she found, she committed to sourcing mulesing-free merino wool for her line of knitwear and tailored clothing. Still, she recognizes that it can be challenging to truly trace things through the chain. “After I learned about mulesing, I started asking all of our textile suppliers — ‘is the wool from this farm or that farm?’ It can be very difficult to get this level of information. I can’t even say that all of our wool is mulesing-free — maybe it’s 90 percent? — because sometimes fibers are mixed, like wool-linen, and then it becomes complicated to trace things. But at least for our merino wool tailoring and knitwear, I can say it’s mulesing-free wool.”

I was impressed by Neuberg’s candidness and willingness to discuss some of these challenges of fully tracing things through an increasingly fragmented, globalized, and complex supply chain, even without me pushing back on how something such as animal welfare can be verified. For me, it showed that Neuberg’s intentions are genuine, and she’s trying to navigate a complicated system in the small ways she can. In a 2009 article in The Guardian, Madeleine Bunting writes about why “small is beautiful” as an idea keeps reappearing. “[I]t incorporates such a fundamental insight into the human experience of modernity,” she writes. “We yearn for economic systems within our control, within our comprehension, and that once again provide space for human interaction – and yet we are constantly overwhelmed by finding ourselves trapped into vast global economic systems that are corrupting and corrupt.” Perhaps that’s why I find De Bonne Facture appealing — along with the beautifully designed clothes, it suggests that it can still be worthwhile to make small choices towards a better world.

You can find De Bonne Facture at No Man Walks Alone and Division Road (two sponsors on this site), Trunk Clothiers, Mr. Porter, Kai D. Utility, East Dane, Cultizm, Ryland Life Equipment, and De Bonne Facture’s website. For more of Déborah, you can read her interview at Outfit Dissecting (her portrait above was taken by the very talented Lulu Graham, author of the blog). You can also follow De Bonne Facture on Instagram and Facebook. Finally, those lucky enough to be in France can visit the company’s new studio, showroom, and shop at 63 rue Sedaine in Paris.