Two years ago, at a black-tie gala held at the Jazz at Lincoln Center, nearly 1,000 guests gathered to commemorate Brooks Brothers’ bicentennial anniversary. While sipping on themed cocktails named “Modern Classic” and “Golden Fleece,” guests enjoyed an all-American jazz program befit for an all-American clothier. Since their founding in 1818, Brooks Brothers has defined classic American men’s style, invented the ready-to-wear suit, and dressed nearly every US President. Brooks Brothers CEO Claudio del Vecchio, who has been widely credited with reviving the company since it fell out of favor under previous owner Marks & Spencer, told The New York Times that he’s working to reinforce a culture. “I have to make sure that we are building a company that will last after me,” he said while sitting at his 346 Madison Avenue office, where his polished mahogany desk faces an antique grandfather clock once owned by the store’s founder, Henry Sands Brooks. “I don’t want to be here another 20 years. Forget about another 200 years. It’s really about trying to build a culture that will last longer than the business. That will make it very hard for the next guy to screw it up.”

Last week, Brooks Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, making it the highest-profile men’s clothier to do so during the coronavirus pandemic. The company says they plan to close about 51 of their stores, a decision they attribute to the toll of mass shutdowns. This comes on the heels of their announcement that they’ll close all three of their US factories by the end of this summer. So far, Brooks Brothers has shut the lights at their Garland, North Carolina shirtmaking factory, which employs about 25% of the town’s residents. The company’s Southwick suit factory and New York tie factory have been reduced to producing masks, but they too will shutter unless the company can secure a buyer.

Soon, the fashion press will churn out stories about what went wrong at Brooks Brothers. I suspect theories will include something about rampant globalization, rapacious capitalism, corporate mismanagement, and mass-marketization. Brooks Brothers either failed to adapt to changing consumer tastes, or they adapted too much. For diehard trads, the decline of Brooks Brothers will undoubtedly be linked to the decline of Western civilization itself.

This narrative about Brooks Brothers will be familiar to anyone who reads this blog. Once merchants of fine-quality, British- and American-made goods, as well as all things trad and Ivy, Brooks Brothers has since been accused of becoming a watered-down Italian casualwear brand. Ivy Style enthusiasts often blame mismanagement: Brooks flirted too much with trends, relied too heavily on discounting, and continually slashed the quality of their goods. While I don’t think these assessments are unfair, I think they miss some of the underlying cost structures that led to these business decisions. Brooks Brothers’ downfall has been decades in the making. The factors that made the label popular with many people today are the same ones that led it down a long, torturous road that ended in a Chapter 11 filing.

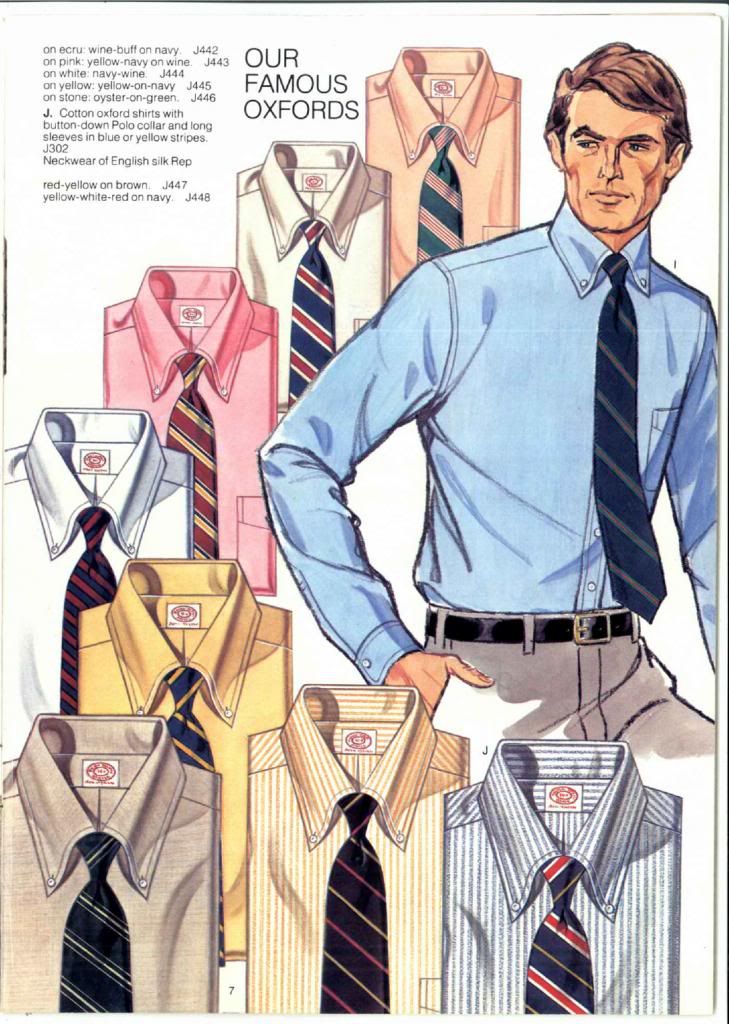

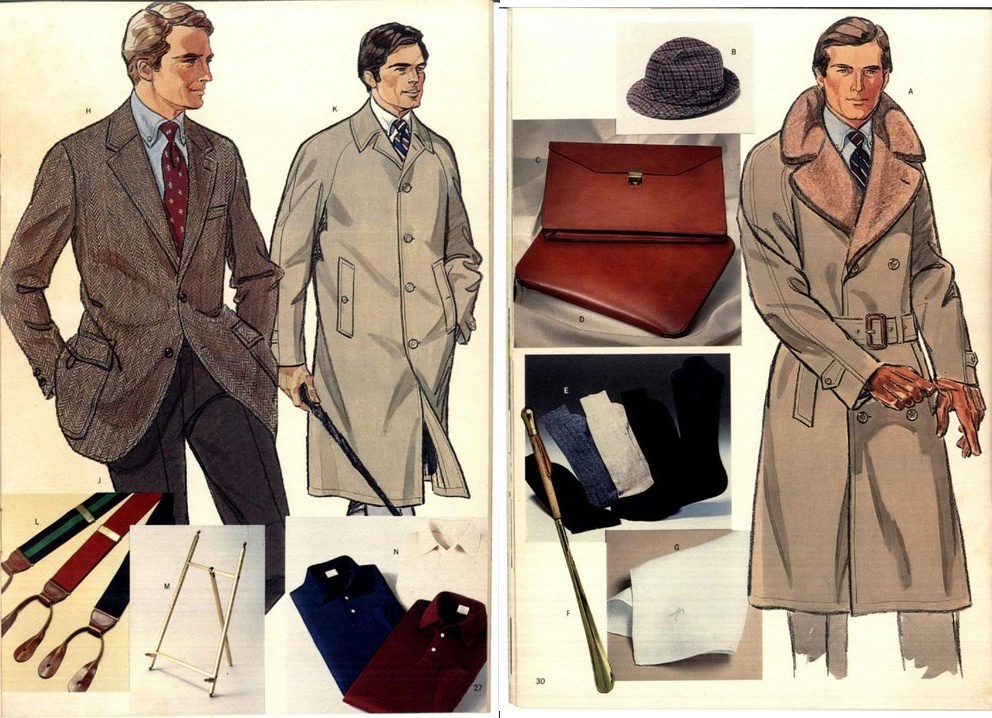

To be sure, Brooks Brothers occupies a special place in American history. Since their founding in 1818, the things they’ve introduced to American men have become the hallmarks of this nation’s style — the unlined button-down collar, camel-colored polo coat, bleeding madras, reverse-striped ties, English foulards, Shetland sweaters, and Scottish tweeds. In 1849, they transformed the tailoring industry with the first-ever ready-to-wear suit, making tailoring more affordable and widely available to all. This set up the suit at the end of the 19th century as an optimistic symbol of snappy progress. The monochromaticity of a dark suit paired with white broadcloth and polished shoes constituted a new capitalist aesthetic and a harbinger of modernity. And after the company debuted its iconic No. 1 Sack Suit in 1900, the term “sack suit” became a shorthand for American style. The Brooks Brothers suit has carried American men from the turn of the 20th century and into “the jazz clubs of the Roaring Twenties, through the dark days of the Great Depression, on to college campuses in booming postwar America, and forward to the present day.”

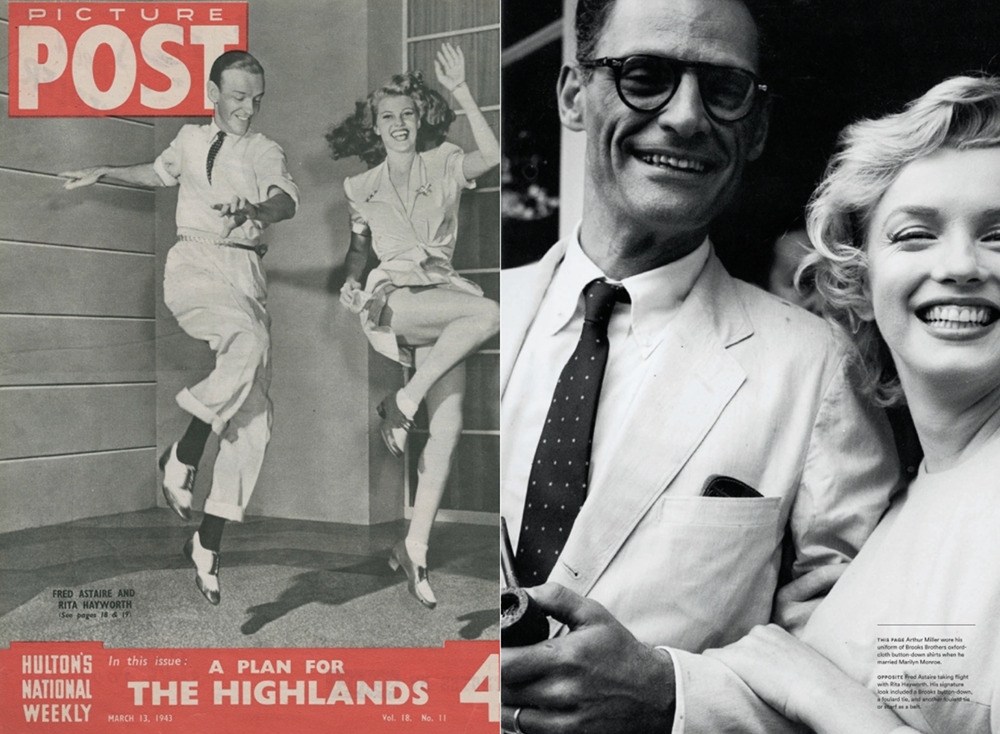

However, while Brooks Brothers taught many American men how to dress, they did not, in fact, dress a great percentage of American men. For much of their history, Brooks Brothers mainly outfitted the American elite: presidents, preps, and members of the professional-managerial class, as well as those influential in the arts, business, politics, media, or medicine. In 1946, the last member of the Brooks family to own the company, Winthrop Holley Brooks, sold Brooks Brothers to the department store chain Julius Garfinckel & Co. In the ensuing years, Brooks Brothers bought bespoke shoemaker Peal’s intellectual property, dressed Clark Gable and then-Senator John F. Kennedy for the weddings, and famously introduced a women’s version of their men’s pink dress shirt. In 1988, the company was sold once more, this time to Marks & Spencer, a major British multinational retailer headquartered in London.

Before the 1980s, most men couldn’t just saunter into a Brooks Brothers and get fitted in the kind of clothes that have since become the company’s legacy. They either didn’t have a Brooks Brothers store near them or were priced out of the goods. Instead, many who favored a Brooks Brothers look bought their apparel from the countless number of haberdasheries that looked to 346 Madison Avenue for direction. Manhattan-based clothier Winston Tailor, also known as Chipp, used to travel to the Midwest to meet clients. At these trunk shows, men ordered natural-shouldered, hook-vent coats inspired by Brooks Brothers’ tailoring. Sitting adjacent to elite colleges and prep schools were also independent clothiers such as J. Press and The Andover Shop, who sold preppy blazers and Shetland sweaters to well-to-do students. This variant of Brooks Brothers’ style, known as Ivy Style, would later spread to other schools and become part of the American dress canon as an insouciant collegiate look.

For a time, Brooks Brothers advertised their oxford cloth button-down as “The Most Imitated Shirt in the World.” In a February 1926 issue of Men’s Wear, one writer described a “progressive” shop in Los Angeles that copied Brooks Brothers’ shirts down to their last detail — the stitch count, the shape of the tails, and of course the soft contours of that collar roll. When asked whether they had any left on post-holiday clearance, the clerk smiled and said: “Why those were all gone long ago. Scarcely any remained to put on sale. We get fresh shipments every month, and can scarcely keep them in stock.” Even the imitations were in short supply. Today, collar-roll connoisseurs have been known to order shirts from tiny mail-order shops that promise to deliver that 1960s Brooks Brothers look. Or they trouble their tailor to move their collar-point buttons by as little as an eighth of an inch to achieve an unfussy appearance that’s internet approved.

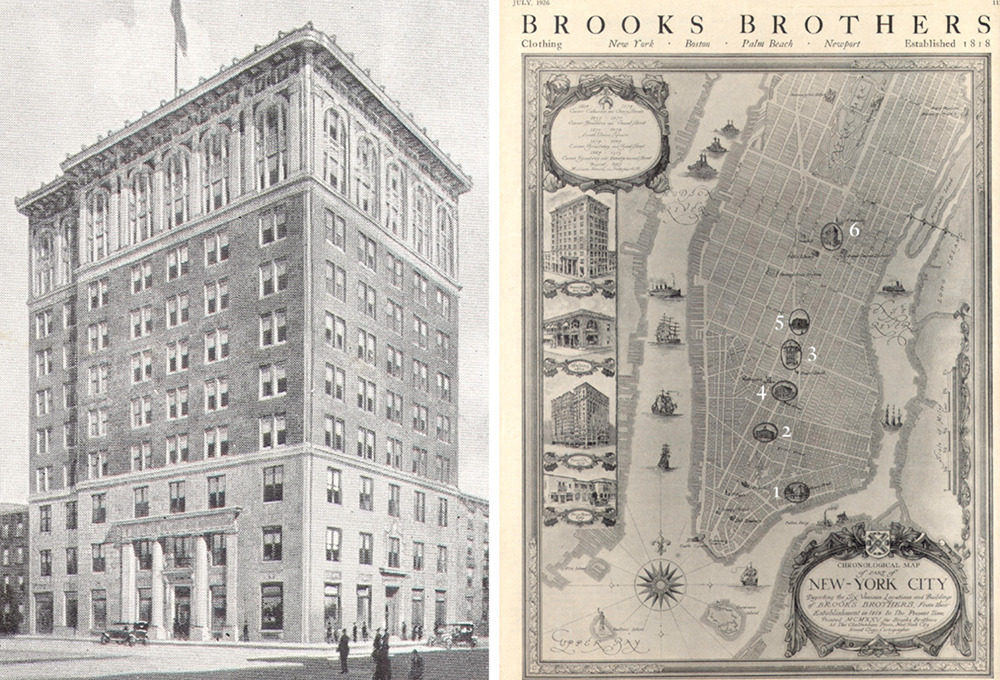

In 1971, Brooks Brothers had a grand total of just 11 stores throughout the United States. These stores were located in the densely populated urban centers of Manhattan, Boston, Chicago, Washington DC, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Scarcely any were located in the Midwest; none were in suburbs or small cities. By the time the company was sold to Retail Brand Alliance in 2001, there were 150 Brooks Brothers locations in the United States and Japan. Today, there are 500 stores worldwide. Roughly 250 of them are in the United States and about 100 of those are outlets. Most men, including me, came into Brooks Brothers during this expansionary period. As stores opened near us, and goods eventually became more affordable, it became easier to own a Brooks Brothers suit and a button-down shirt. But over time, this complex network of real estate leases proved to be a ticking time bomb.

Last month, I interviewed former and current Brooks Brothers executives about the company’s downfall. The story, which was published at Business of Fashion, shows how quickly the company slid into bankruptcy because of structural issues. Sources familiar with the company’s finances say that Brooks Brothers was still profitable in 2013. The company was debt-free, promoting its newly-launched Red Fleece line, and enjoying a bit of publicity from having made all of the men’s costumes in the film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. In 2015, however, the company started operating at a loss and hasn’t been able to recover since. Speaking with The New York Times, Del Vecchio says the company has a debt of “less than” $300 million.

Efforts to save the company have been stymied by the company’s retail footprint. In the US, Brooks Brothers’ stores are often located in premium, high-rent areas. These massive retail spaces were originally built to display racks of ready-made suits and all of their accoutrements. Their astronomical rents require brisk sales of tailored suits, which today retail for as much as $1,698, but are often discounted. The company’s flagship in San Francisco, for example, is located downtown near the city’s historic Union Square, a block away from Gucci and Saks Fifth Avenue. It’s a 26,000-sq.-ft, four-story location filled with the company’s casualwear, women’s collections, home goods, and men’s tailoring. Real estate in San Francisco is among the most expensive in the US, and this portion of downtown is just about the most expensive in San Francisco.

However, over the last few decades, tailored clothing has taken up a diminishing share of men’s wardrobes. What started as a closet full of suits eventually moved to sport coats, until the sport coats were abandoned and only the dress shirt remained. As working professionals replace tailored jackets with merino knits and polyester fleece vests, traditional clothiers have struggled to make up for the loss in profits. A two-week wardrobe full of sweaters, chinos, and sneakers isn’t nearly as profitable as one with sport coats and tailored trousers. Or better yet, seasonal suits with all the things you need to wear with them. Today, the company derives about 27% of its sales from non-iron button-up shirts alone — this is just a fraction of their shirt business. Many men who purchase their dress shirts at Brooks Brothers don’t even wear a tie, let alone a jacket. Consequently, Brooks Brothers has struggled to get the same return per square foot at many locations. Of Brooks Brothers’ 150 full-line US stores, just 40 are responsible for 80 percent of sales, according to a person familiar with the company’s performance. Costly remodeling projects also didn’t help.

Brooks Brothers has been mostly unsuccessful in trying to extract itself from its poor-performing leases. In some cases, multiple properties can be managed by the same property group. In such instances, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to get out of the poor performing locations while holding onto the good ones. Other times, contracts will have a built-in penalty if Brooks Brothers breaks their lease. Consequently, the company has weathered on at these locations, even as they operate at a loss.

This complex network of real estate deals narrowed Brooks Brothers’ business options and pushed them further downmarket. Over time, the collections became ever more contemporary and generic to pay for expensive real estate. Items such as luxury leather sneakers, stretch denim jeans, and contemporary fits and styling lead some to describe the new Brooks Brothers as “watered-down Italian.” In 2013, the company introduced their lower-priced Red Fleece line to draw in younger customers. Last year, they replaced their Edward Green and Alden-made shoes with two new collections produced in Italy. Their new shoes feature sleek lasts, logo-stamped uppers, and rubber outsoles so they feel more comfortable to men who are accustomed to wearing sneakers. Meanwhile, older customers balk at choosing between a growing array of sizes (shirts now come in extra slim, slim, fitted, classic, relaxed, and specialized) and lower-rise suit trousers.

To make up for the poor performing locations, the company opened up even more full-line stores, but again with little success. Many failed to meet sales goals or were located too close to existing stores, splitting the customer base. To make up for these further losses, the company has had to open more outlets, which has diluted the brand’s value in the eyes of core consumers. Of the 250 Brooks Brothers locations in the US today, about 100 are outlets that mostly carry lower-quality goods made expressly for them.

One executive told me of the challenges of trying to sell stock early in the season. “With the fashion delivery schedule, you might get spring items in February and fall items in August. But people aren’t shopping for their fall or winter coats until November,” he explained. “By then, it’s already discount season. When something has been sitting on the sales floor for months, sales associates start to lose enthusiasm for the product. It then becomes harder to sell that item. So every season, we were just constantly sitting on all this unsold stock.”

To draw customers into their stores earlier in the season, Brooks Brothers has increasingly relied on promotions. For the last year, I’ve received about two emails per week about the company’s “limited time offers” — 4 shirts for $199, 2 suits for $1,499, and 70% off clearance. As one insider put it, the company has become a “$50 shirt and $500 suit,” which puts them in direct competition with entry-level brands such as Charles Tyrwhitt, Suitsupply, and UNTUCKit. (For a short period, a small number of UNTUCKit’s premium shirts were manufactured at the Brooks-owned Garland Shirt Factory). “Even Amazon has gone and made shirts to compete with Brooks Brothers’ button-down oxfords and non-irons,” a former executive told me. “For the average consumer who is looking for a decent quality shirt at a certain price, these shirts are not bad. If you look at them as a ‘garmento,’ you poo-poo them. But for the average person, they’re looking at price and price-value.” When I ask how is it possible that the company that invented the oxford button-down is unable to command a premium in the eyes of customers, he sighed. “That’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it?”

In a letter written to his customers in 1939, company president Winthrop Holly Brooks wrote something of a manifesto. He opened by gently poking fun at the various fashions aimed at contemporary young men. As he put it, the clothes were a “modern version of Kampus or Kollege Kut Klothes before the World War” or the “country-squire … woolly and horsey and loud as the law allows.” At the end of this letter, he claimed that at Brooks, “rarest perhaps of all, are to be found clothes of the timeless kind, not ‘British,’ not ‘American,’ not ‘Broadway,’ not ‘French,’ not ‘Colonial,’ not ‘Hollywood,’ or ‘College,’ but the kind that men of good taste, nurtured by generations of gracious living and daily contact with others of the same mode of life in their own and other countries, wear and have worn for years — as naturally as they do their skins or their eyebrows, and are as loathe to change in essentials as might be the leopard to change his spots.”

When Marks & Spencer bought Brooks Brothers, many menswear enthusiasts saw the clothier as situating themselves closer to the leopard’s lair. As these companies sought a higher return on their investment, they expanded Brooks Brothers’ retail footprint to capitalize on the brand’s cache. This set up a complex network of real estate leases that would prove deadly. As rents soared and tailored clothing sales in the United States declined, Brooks Brothers has had to increase their international points of sale to make up for the loss in profits. In the last seven years, global sales have reached as high as $1.2 billion, but have mostly hovered around $1 billion per year. In 2013, $880 million of those sales came from within the United States; in 2019, that figure shrank to $660 million. That heritage-minded American professional isn’t Brooks Brothers’ only customer anymore. The brand has become increasingly dependent on outlet and international shoppers.

When we think of the problems that plague the fashion industry, Brooks Brothers neatly sits at the intersection of many of them. With about 250 stores and outlets in the United States, they’ve been particularly vulnerable to rising rents and the general decline of brick-and-mortar sales. Meanwhile, as men have started to dress more casually, they’ve only ever turned to Brooks Brothers for non-iron shirts and flat-front chinos. Such items don’t earn the company as much money as tailored suits and sport coats. Worst of all, they’re treated as commodities — totally interchangeable like white t-shirts and green apples — which makes them ripe for comparison shopping and discount hunting. Brooks Brothers’ forays into high fashion and casualwear haven’t been successful enough to save the brand, either.

Add to this the challenges of manufacturing clothes in America. When asked about the company’s decision to shutter their three US factories, a Brooks Brothers spokesperson wrote to me: “It is well known that domestic manufacturing is costly and that these factories have rarely been profit centers. Shutting down our domestic factories is an outcome we would like to avoid and all opportunities to avoid this are still on the table and being explored.” A former Brooks Brothers executive added that the Southwick suit factory had a harder time finding skilled labor when the Trump administration put harsher immigration policies into place. Nearly all the workers at Southwick are first-generation immigrants.

In the usual narrative about Brooks Brothers, the company lost its way when it cut quality and experimented with trends. But those decisions came after Marks & Spencer expanded the company’s retail footprint. Indeed, they were made to pay for the hundreds of store locations spread throughout the United States. In hindsight, it’s easy to say that the company shouldn’t have expanded, but how many who lament Brooks Brothers’ demise today would have been customers in the 1970s? For generations, Brooks Brothers’ preppy and pinstriped clothes were symbols of success. As The New York Times wrote: “It personified East Coast success in the Kennedy vein, and its Madison Avenue flagship, a limestone Italian Renaissance building, became a pit stop for commuters hopping the train from Grand Central to family life in the suburbs.” It takes a bit of honest self-reflection to say whether one would have been able to shop at such an esteemed Manhattan clothier.

The future of Brooks Brothers now hinges on who will buy the company. According to fashion trade journal Women’s Wear Daily, the two leading contenders include Authentic Brands Group in partnership with Simon Property Group and Brookfield Property Partners, and WHP Global, the newly formed brand management firm headed by Yehuda Shmidman. “With its war chest of cash and its partnership with mall developers, ABG is seen as the company to beat,” Jean Palmieri writes at WWD. “If its bid is accepted, ABG is expected to mimic the strategy it used to purchase Forever 21 for $81.1 million in February. In that deal, ABG and Simon each took a 37.5 percent stake in the intellectual property and operating business, while Brookfield took 25 percent. The 448 stores were kept open, the company hired a new CEO, former H&M executive Daniel Kulle, and signed licensing deals in other countries.”

Brien Rowe is a consumer and retail banker at DA Davidson. For my article at Business of Fashion, he added: “If a buyer comes in and purchases the business in bankruptcy, they’ll be able to cherry-pick assets. Certainly, their intellectual property has great value, their online business, their customer list — those are still there. Out of 250 stores, 50 or 75 I’m sure will still do well. A certain number will survive and continue to run with the Brooks Brothers name.”

It’s not hard to envision a future where the majority of Brooks Brothers’ grand stores have closed, and the brand lives on as one of dozens of button-down shirts piled on the tables at Macy’s, or perhaps even sold through Amazon. Or, best-case scenario, the brand returns to its pre-1980s glory. With just a few flagships in select major cities and a robust custom tailoring program, perhaps it can supply men with quality goods, even if those items are sold at higher prices. I wonder if the fall of Brooks Brothers isn’t just another example of how the middle of the market is untenable for classic men’s clothing. Perhaps the only way out is to go back upmarket where the company is again out of reach for a larger number of consumers, or go further downmarket to the point where it’s even less inspiring. Mid-tier retailing with a large number of stores seems to be a dead business model in fashion.