Menlo Park, a suburb located outside of San Francisco, is known for being the venture capital engine for California’s tech economy. The city today is a portrait of serenity, with its multi-million dollar homes, well-manicured lawns, and wide, tree-lined streets. In 1969, however, when Victor Cizanckas was appointed as the city’s new police chief, Menlo Park and the rest of the Bay Area were in turmoil. The decade’s protest movements were met with increasing state violence, sometimes verging on open warfare. As images of attacking police dogs and civil rights abuses flickered across television screens, Black leaders in the neighboring Belle Haven and East Palo Alto communities organized marches to demand equal treatment. At UC Berkeley, Mario Savio stood at steps of the university’s admissions building, Sproul Hall, where he famously urged students to put their “bodies upon the gears” in defense of free speech. That night, police officers moved in and arrested nearly 800 demonstrators, making it the largest mass arrest in California’s history. And just two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., with riots raging across the United States, the Oakland police engaged in a shootout with the Black Panther Party, killing young Bobby Hutton.

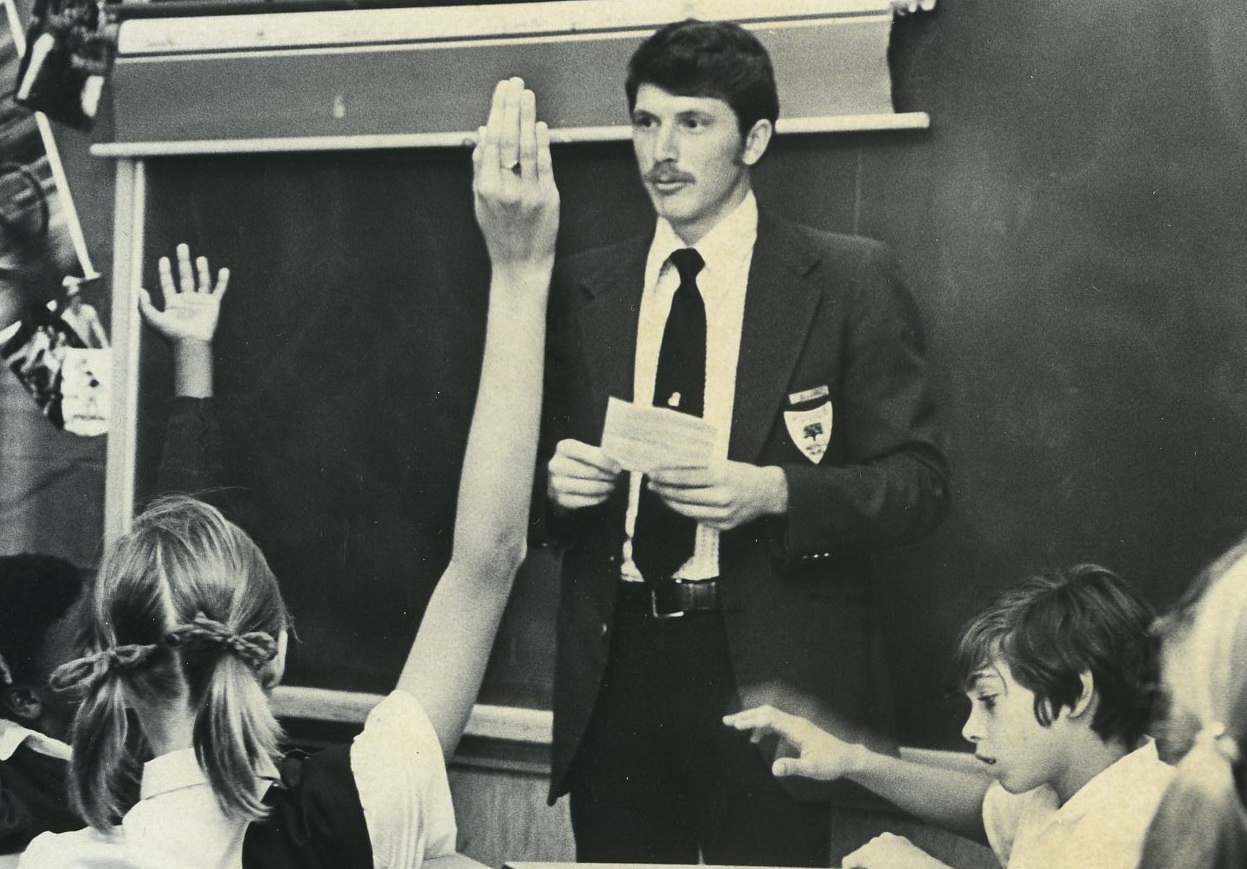

It’s no wonder so many Americans that decade had such little faith in policing, including residents of Menlo Park. To help rebuild that trust, the newly appointed police chief, Cizanckas, then 39 years old, decided it was time for the most superficial reform — he’d change the department’s uniform. For years, Menlo Park’s officers wore the same, neatly pressed, dark blue attire that commanded military authority. Cizanckas switched out that uniform in favor of a white shirt, dark tie, pair of charcoal slacks, and an olive green blazer. Handcuffs and firearms were hidden underneath the coat, while the shiny metal badge was replaced with a soft embroidered patch. Cizanckas even dropped the department’s use of black-and-white police cars, military stripes, and ranking. “Sergeants” were now called “managers,” while “lieutenants” became “directors.” “We should measure what we do and treat our command staff as managers,” Cizanckas told The New York Times, “not as members of a military hierarchy.”

Since the 1970s, over 400 police departments have engaged in some kind of fashion experiment. In Burnsville, Wisconsin, police chief David Couper dressed his officers in a dark blue sport coat, white shirt, and French blue trousers, making them look like airline attendants. He also discouraged officers from wearing reflective aviator sunglasses when making traffic stops. “Make eye contact,” he suggested, “make sure they know you’re a human being.” Many departments tried lightening the color of their uniforms in hopes that officers would appear less intimidating. In some suburban and countryside towns, officers wore the color of the land, such as juniper green and walnut brown. And by the mid-1980s, NYPD officers tried wearing baseball caps so they would “look more user-friendly,” according to The New York Times.

These reforms were a way for police departments to tap into what psychologists call “enclothed cognition,” which is the theory that your clothes can affect your thought processes and behavior. Much like how a white lab coat supposedly helps you concentrate better on tasks, a demilitarized police uniform should make officers less authoritarian (or so goes the theory). But results are mixed and unclear, and scholars are divided in their findings. While some found that officers exhibited lower “authoritarian characteristics” after wearing their new uniforms for just 18 months, others attribute the shift to secondary effects. As departments adopted less militaristic uniforms, they may have attracted recruits who were less likely to be authoritarian in the first place, just as a matter of disposition.

Fifty years later, officers complain about a culture of slovenliness. The new dress-down uniform makes officers look more approachable, yes, but the original monochromatic outfit is designed to project authority. People are more likely to recognize your authority when you look intimidating — and that’s the point. In a series of letters to the policing blog Calibre Press, older officers complained about new recruits looking less than respectable in their polo shirts, baseball hats, and canvas boots (instead of the previous standard of leather). One said that he was tired of officers looking like overpaid mall cops. “I also believe it takes away from the image we should project … that of bearing command,” Texas Lieutenant Carl Crisp added. “You want respect? Look respectable.”

Three years ago, Kevin Davis, then Baltimore’s police commissioner, abruptly disbanded all his plainclothes teams when he found seven members of a task force were indicted on federal charges of stealing guns, drugs, and money. “I don’t want the jeans, I don’t want the t-shirts,” he sharply told The New York Times. “I want your brass badge attached to your chest. I want the patches on your shoulder. I want you to look like a cop, because I can’t ask you to act like a cop unless you look like one.”

The issues raised since George Floyd’s murder are too deep to be addressed through a green blazer. Yet, the history of police uniforms provides us with a fascinating view into the very history of policing itself. Aarian Marshall of City Lab wrote, “What we’ve asked — and allowed — police officers to wear throughout history has influenced what we’ve expected of them, how we feel about them, and how they feel about themselves.”

Law enforcement officials didn’t always wear uniforms. In colonial America, the law was enforced by roving bands of able-bodied men. In the north, these patrols were known as watchmen for how they walked city streets to monitor for suspicious characters. In the south, patrols were tied to something more nefarious: the institution of slavery. As the Black population boomed, especially after the introduction of the cotton gin, so did White fears of Black resistance. So large plantation owners often hired patrollers to instill fear and obedience among Black slaves. Patrollers suppressed revolts, captured runaways, and punished the non-compliant, as well as the compliant.

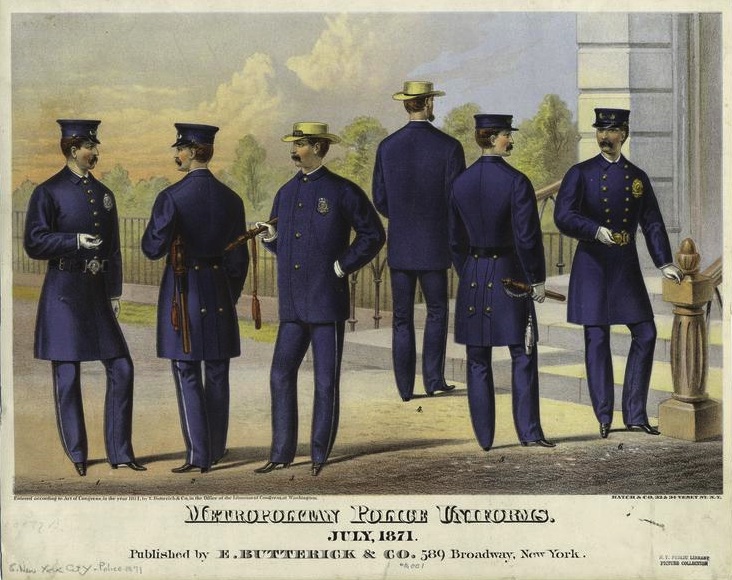

This loosely organized system continued until nations industrialized and towns became more crowded. So in 1829, British statesman Sir Robert Peel formed the Metropolitan Police Service in London to replace the previously disorganized system of parish constables and watchmen. Peel wanted to distinguish officers from civilians as a way to show they’re a professional class, but he faced a PR problem. British citizens were sensitive to how a centralized, armed force, such as France’s gendarmerie, could threaten their liberty. To put citizens at ease, Peel dressed law enforcement officers in a dark blue, long-tailed coat, which contrasted against the British military’s scarlet, short-tailed coat. The earliest use of a blue-coded police uniform was thus aimed at cultivating civilian trust, as well as giving the impression of safety and competence.

Peel’s ideas eventually made their way to the United States, where similar police forces formed in urban centers such as New York City and Boston. The NYPD was closely modeled after the Metropolitan Police Service in London, following its quasi-military hierarchical structure, with military command, rank, and order. With this came a regulated uniform: long, single- or double-breasted coats worn with matching trousers and either cloth caps or fire-style helmets. New York City officers initially resisted wearing their new uniforms for fear of looking like British bobbies (slang for a British police officer, named after Robert “Bobby” Peel). There was a strong anti-British sentiment among the public and officers worried about being openly mocked, but they eventually acquiesced by the 1850s. In 1869, NY Superintendent John Kennedy issued an order announcing that police officers will also have to wear white cotton summer gloves, which “must be of good quality, and be kept clean.” Gradually, these ideas spread West throughout the United States — along with the monochromatic blue uniform.

By the turn of the 20th century, police departments were run like medieval patronage systems. Mayors appointed their police chiefs, and police chiefs recruited officers from their network of friends and family. In this tightly-knit social system, officers would then protect mayoral interests. During the Prohibition era, leaders of organized crime funded mayoral campaigns in turn for having police chiefs look the other way. Officers also routinely engaged in criminality: they illegally wiretapped people, beat suspects, took bribes, engaged in entrapment, and falsified evidence.

During interrogations, officers beat suspects with garden hoses, pieces of tire, sausage-shaped sandbags lined with silks, and blackjacks soaked in water, wrapped in a handkerchief, or covered with soft leather so as not to leave any visible marks. In his book Police Interrogation and American Justice, law professor Richard Leo outlines some other prominent forms of deniable coercion: administering tear gas in a large wooden box placed over the suspect’s head; thrusting a spraying water hose down his throat; and forcing him to walk barefoot across an electrically wired mat, causing sparks to fly. The Sweat Box treatment, which dates back to the Civil War, involved placing a suspect in a small, dark cell for days or weeks at a time, while an adjoining stove produced scorching heat and pungent odors. “Sickened, perspiring, and unable to endure the rising temperature, the suspect was compelled the confess,” Leo wrote.

In 1929, President Hoover tasked the Wickersham Commission with conducting the first-ever comprehensive study of law and crime in the United States. The commission uncovered these abuses and found that the average American had such contempt for the police, the criminal justice system was all but unworkable. Much of the commission’s report, laid out in fourteen volumes, was eventually obscured by hardships Americans endured during The Great Depression. Nevertheless, one volume — Lawlessness in Law Enforcement — shocked the nation and ushered in a more professional era of policing. As criminologist Sergio Herzog wrote in his 2001 essay in Policing and Society:

Influenced by the progressive movement and by the growing American emphasis on bureaucracy in business and industry, at the start of the 20th century the police as an institution underwent a gradual process of professionalization. It aimed at transforming the police into an effective and professional body free of political influences and local corruption, hence greater militarization. These processes were reflected in the adoption and implementation of essentially military organizational and administrative principles and in the dissemination of the institutional ideological messages of militarism among police officers. According to the newly defined “professional” police goals, law enforcement became the exclusive and main specialization area of the police, to be formulated in terms of the intentionally quasi-military metaphor, “war against crime” (rather than a campaign or a struggle against it) by aggressive military means.

The history of policing in America has been one of a constant push and pull between the community side and military side, with the second mostly winning. In 1968, a tumultuous year marked by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy, urban race riots, and anti-war protests, Americans watched in horror as attendees at the Democratic National Convention were met in full force by 23,000 members of the National Guard and Chicago police. During that year’s presidential election, Richard Nixon tapped into the nation’s fears. He campaigned on “law and order,” promising that election day would be a “day of protest for the forgotten American.” This group included those who “obey the law, pay their taxes, go to church, send their children to school, love their country, and demand new leadership.” One television ad included flashing images of rioters, looters, and burning buildings. “I pledge to you, we shall have order in the United States,” Nixon ominously said in a voiceover. The ad ended with his slogan: Vote Like Your Whole World Depended On It.

Shortly after he took office, Nixon tied drug abuse to criminality and promised to wage war on both. For the “Silent Majority,” drug users were not alienated youths trying to cope with a fundamentally broken society, but criminals who attacked the very moral fiber of this nation, and thus were deserving of only punishment and incarceration. And so, Nixon continued the “War on Crime” started by his predecessor, President Johnson, as well as launched a new “War on Drugs,” which reduced social welfare spending and increased law enforcement and police surveillance. “The rhetoric of ‘war’ influenced the way many police departments across the country approached their work,” Roman Mars said in a 99 Percent Invisible episode. “War also requires specialized equipment — and in the late 1960s, the government established the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, a now-defunct federal agency that gave money to local police departments to buy heavy-duty, crime-fighting tools, including riot gear, bulletproof vests, armored vehicles, and weapons.”

This trend towards militarization continued through the 1980s and ‘90s, and then accelerated after the 9/11 attacks, when President Bush launched a new “War on Terror.” Over time, along with the rhetoric of war, the militarization of our police forces has come through various policy pipelines. President Johnson’s Law Enforcement Assistant Act of 1965 created a grant-making agency within the Department of Justice, which allowed for the transfer of military-grade hardware into police departments. There is also the National Defense Authorization Act of 1990 and the 1033 Program of 1997, which have allowed for even more military surplus transfers. These include small arms and munitions, armored humvees and MRAPs (mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles), and accompanying military-grade uniforms. In 2015, after the clash between police officers and protestors in Ferguson, Missouri, President Obama signed an executive order to make it more difficult for police departments to get their hands on military-grade equipment. But in 2017, President Trump rolled back that order, and former Attorney General Jeff Sessions dismissed the criticism as “superficial concerns.” In recent weeks, Trump has adopted the same militaristic language, tweeting for law enforcement officials to “dominate” protestors with “overwhelming force.”

Along with their “dress blues,” officers now wear elements of battle dress, such as camouflage fatigues, tactical vests, and facial shields. It’s unclear whether wearers are more likely to act violently in these uniforms — they typically wear their military gear in highly charged situations, which makes it difficult to parse whether the uniform or context drives behavior. But historically, such tactical gear has been disproportionally employed in communities of color, which has other effects.

In a 2018 paper published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Princeton political science professor Jonathan Mummolo set out to find the real effects of militarization. Using rare geocoded census data of SWAT team deployments in Maryland, he showed that militarized police units were more likely to be deployed in Black communities, even after controlling for local crime rates. Zooming out and using nationwide panel data, Mummolo also showed that police militarization does little to enhance officer safety or reduce crime. Instead, it just diminishes police reputation and local trust. “In the case of militarized policing, the results suggest that the often-cited trade-off between public safety and civil liberties is a false choice,” he concluded. From Mummolo’s paper:

Indeed, in the control condition in the SSI data, when asked how much confidence they had in police in the United States, the mean response among Black participants was 21 percentage points lower than among white respondents. Why then, do we observe such similar effects among the two groups? One explanation is that different mechanisms are operating within each group to produce effects of similar magnitude. For example, white respondents may react negatively to militarized images because they clash with their baseline perception of law enforcement, while Black residents may react negatively because they conjure memories of discrimination. […] [M]ilitarized policing can impose reputational costs on law enforcement, likely in unintended ways. This is troubling, since prior work shows that negative views of police inhibit criminal investigations and are associated with stunted civic participation.

Such issues are too deep to be resolved through a change in uniforms alone. The lasting legacy of Cizanckas’ green blazer experiment in 1969 is more about how we view police officers, rather than changing police behavior. Cizanckas helped burnish the battered public image of policing at the end of a turbulent decade — and, even then, it was mostly in a suburban White community. In 2016, when a Missouri police department changed the color of the SWAT fatigues from military green to the more “traditional” policing blue, critics reasonably laughed it off as superficial. Police uniforms aren’t really the issue; they’re just a visible layer of a mostly invisible system. That system, which the state uses to exert control, is defined by our history, institutions, policies, and culture. Police uniforms, then, are simply how we dress the law.