It’s been barely a month since J. Crew filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, making it the first major retailer to fall during the coronavirus pandemic. Since then, an alarming number of fashion-related businesses have followed, including Neiman Marcus, Aldo, John Varvatos, JC Penney, and J. Hilburn. This month may lay claim on one of the largest men’s clothiers. In a phone call that took place late last April, Brooks Brothers CEO Claudio del Vecchio allegedly told a group of senior executives that that company plans to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy this June.

I first heard about the phone call last month while I was working on a story about how Brooks Brothers is planning to shutter all three of its US factories. Since finding the bigger headline, I’ve been interviewing former and current Brooks Brothers executives, who were willing to share the insider story of how the brand has found itself in this position. This morning, Business of Fashion published my feature. The story is about a lot more than the spread of Casual Friday or the coronavirus pandemic (although those certainly contributed to Brooks Brothers’ downfall).

The situation stems from a massive network of long-term real estate leases, which stretch back to the 1980s. Under the leadership of Julius Garfinckel & Co., Brooks Brothers operated just 11 locations in 1971. By the time Marks & Spencer sold Brooks Brothers to Retail Brand Alliance in 2001, there were 155 stores and outlets in the US and Japan. Today, there are roughly 250 stores in the United States alone — and nearly half of them are outlets. Of Brooks Brothers’ full-line US stores, just 40 are responsible for 80 percent of sales. One executive told me that they could have closed over 100 locations and not seen much change in profits. The fall of Brooks Brothers ties together many things: the decline of tailored clothing, the challenges of running a brick-and-mortar business, and the difficulty of telling an American story during a globalized age. You can read my story over at Business of Fashion.

This morning, Bloomberg reported that Authentic Brands Group is in talks to buy Brooks Brothers. If they do so, Brooks Brothers may live on as just a licensed name — perhaps reduced to a pile of shirts sitting on a Macy’s table, or even sold through Amazon. It’s a remarkable fall for the oldest and arguably most important men’s clothier in the United States. I’ll write more about Brooks Brothers in the coming weeks, as I’m sure there will be a lot more to discuss soon.

Finally, I interviewed Bruce Boyer for my Business of Fashion article. I was only able to use a little bit of what he said since the article had to be concise. However, Bruce’s insights are always interesting to read, so I thought I’d share them here. Below is our quick Q&A on this topic.

While talking with executives last week, some of them mentioned to me that they feel the company has become more Italian in its style over the years, thus making it less identifiably American. Do you feel the same way? Also, do you think there’s been any change in quality?

Brooks was always the place for a man to find decently made traditional clothes at a fair price. It was never about fashion — even though the 1950s saw it that way — it was never about trends for the sake of change. It was about quality clothes at a reasonable price. It had been something of a tradition among devoted customers (such as J.P. Morgan) to bring their sons along to be introduced to the father’s favorite salesman. And thus, the title of their vanity press book Generations of Style made perfect sense. But after the Second World War, after being a family business for 128 years, Winthrop H. Brooks — the last Brooks to lead the clothing company — sold the business to a Washington D.C. department store. After that, Brooks Brothers was sold in 1981 to a corporation, 1986 to a Canadian company, 1988 to a U.K. company, and 2001 to an Italian company. The world had changed in the intervening 55 years since W. H. Brooks had sold out in 1946. The heyday of Ivy League fashion disappeared with something of a wild dance at The Summer of Love, Woodstock, and the Peacock Revolution of the late ’60s.

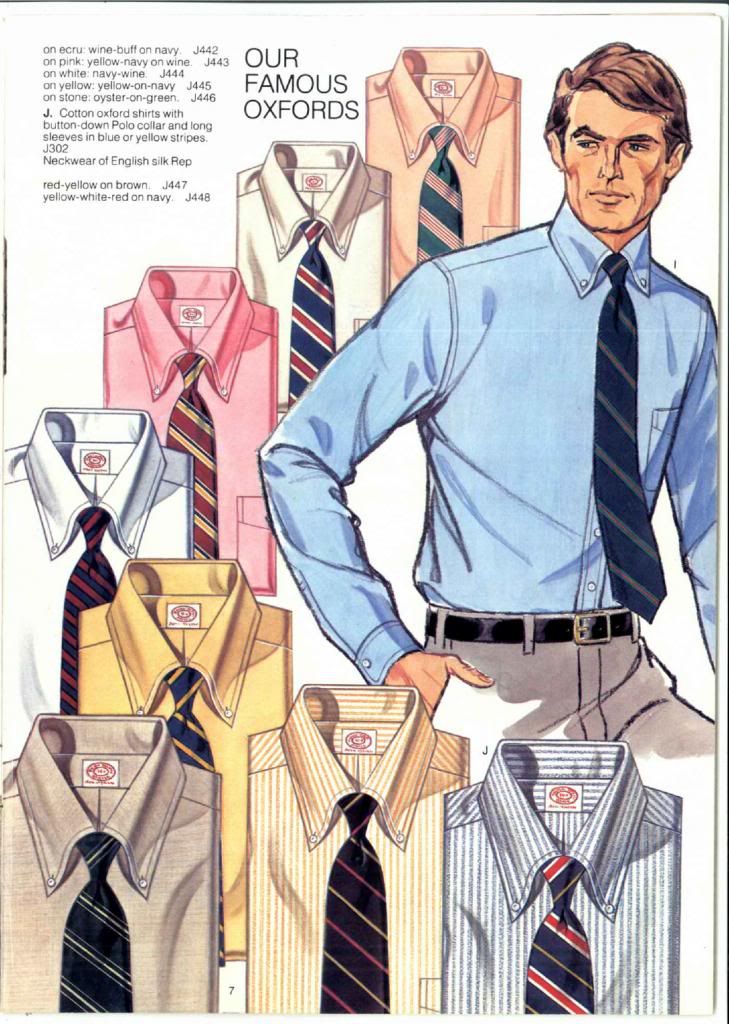

To my mind, no one has known what to do with Brooks since the late ’60s and the legacy has become more and more tarnished, the heritage more faded. Along with that loss, quality has gone down and down. The classic button-down oxford’s soft unfused collar was thrown out for a harder, thicker, non-wrinkle collar. When customers complained, no one listened, until it became clear that the hard, stiff collar wasn’t selling well. Then Brooks Brothers finally re-introduced their old soft collar and cuffs in 2016, but at twice the price! Some die-hard customers felt thoroughly betrayed and disgusted at that point.

The clothing was no longer made in US factories. Tailored garments were now made in Asia, fabrics were dense with synthetic fibers, and customers were so confused by new shirt sizing (Extra Slim, Slim, Fitted, Classic, Relaxed, Specialized?). The company changed the suit silhouette, (including trousers with rises so low they no longer sat on the hips), and added new shoe manufacturers and other Italian-made products (cashmere sweaters were no longer made in Scotland). Many older customers saw the store as a rather downmarket Italian department store. One can understand that an Italian-owned company would want to sell Italian products, but it wasn’t Brooks Brothers’ legendary style of Anglo-American gear. It was a mongrel, a mixed breed, a mutt cast adrift in a highly competitive sea where more and more customers are interested in authenticity and heritage.

As a long-time Brooks Brothers customer and men’s style journalist, why do you think Brooks Brothers has fared so poorly? What are some of the problems you see at the company?

While it seems clear to me what brought Brooks Brothers to its present situation, I have no idea how to fix it. At one time, I had heard that Ralph Lauren was interested in buying it. This was before he renovated the interior of the Rhinelander Mansion at 72nd & Madison. It would have been very interesting because that’s where Lauren started out, and he’s always had a good eye for style and quality. Apparently, nothing ever came of that. It’s terribly sad, a tragedy really, to see an entity such as Brooks Brothers, with such an illustrious tradition and legacy, be dragged so low.

In the ’50s and early ’60s, when I first became a customer, I’d walk onto the main floor and my heart would flutter: the large oval glass display counters flowing over with fine silk repp neckwear, the tables high with Shetland crewnecks made in Scotland, the Peal shoes handcrafted in England, and the Lock tweed flat caps. The room encased in dark wood, with brass sconces and hunting prints. Upstairs were Harris Tweed or Madras sports jackets depending on the season, unconstructed seersucker and flannel, and cavalry twill trousers tough enough for the cavalry.

All of that is gone, and crying over spilled milk has not yet become my hobby. But what has replaced it that is actually better? I don’t have any idea what the more difficult problems were and are. Over-extension? A precipitous drop in quality? Failure to properly train the sales staff? Not understanding their customers? Losing brand identification by dabbling in designer gear? Either way, it’s clear the problems are systemic and deep-rooted. Maybe it’s like a Shakespearian tragedy where you have to kill everyone off at the end to begin again.

Do you think there’s a market for American-made goods and American-styled clothing? Especially at a scale such as Brooks Brothers?

I’ve always been a flag-waver for American-made. There’s a great sorrow to see brands that were started and developed by Americans now being produced offshore. After the Second World War, the US came into its own sense of style. It was Americans who invented casual clothing; it was Americans who were imitated all over the world for our stylish deshabille. After the war, everyone on the globe wanted American jeans, bomber jackets, poplin and seersucker suits, button-down shirts, and penny loafers. It amazed me that all of that wonderful gear has been kept alive by other countries — Japan, Italy, and France primarily — and now is being sold back to us by them as authentic American style. So I see there will always be a market for American style, but who will be making and selling it? At the moment, the clothing retailers who are doing the heavy lifting — those who are inspiring new, inventive, quality approaches to style — are the smaller labels and stores, such as Drake’s and The Armoury. There are also venues such as Blue Owl Workshop, Standard & Strange, Sid Mashburn, Brycelands, Todd Snyder, and a host of others beyond my ken. Nothing the size of Brooks Brothers.