I was recently having a discussion with my friend Voxsartoria about whether there’s a practical difference between bespoke and high-end ready-to-wear. He thinks the difference is not only night-and-day but claims he can tell when someone is wearing something that was made for them. I don’t believe him.

Writers who cover bespoke tailoring will often breathlessly swoon about the Old World fitting rooms on Savile Row and how it feels to have a tailor stretch measuring tape across your shoulders. In the foreward of Anderson & Sheppard’s vanity book, A Style is Born, Graydon Carter says a client’s bespoke pattern is more honest than any autobiography (Carter’s foreward is beautifully written, but not that critical or technical). On the topic of whether bespoke lends any advantages, one of the most sensible and grounded articles I’ve read is by David Isle, which was published some years ago at No Man Walks Alone (a sponsor on this site).

As David notes, comparisons between bespoke and ready-to-wear tailoring are usually complicated by “different makers, different fabrics, different wearers and all manner of other variables that could matter.” In his post, he compares a RTW Formosa sport coat to a bespoke one, both made in the same workshop, according to the same standard, and with the same fabric. The only difference here is that the RTW jacket is cut from a standard pattern and made-up as a finished jacket, whereas the bespoke one is cut from David’s pattern and refined through a series of two fittings.

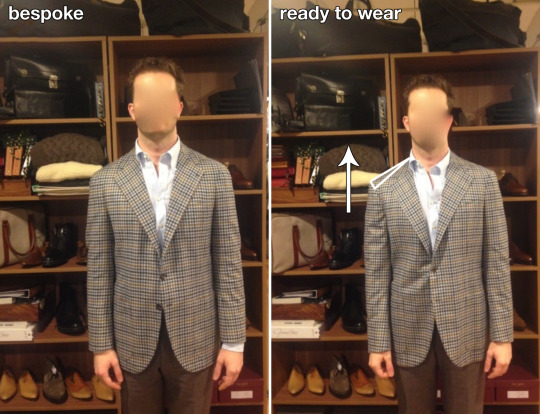

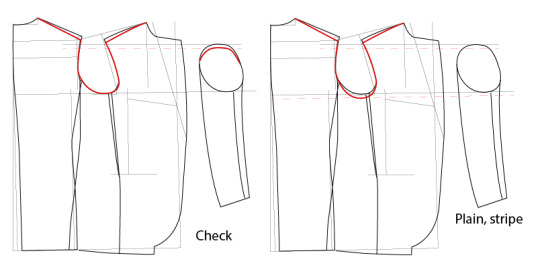

In comparing the two photos below, you can see how the ready-to-wear coat doesn’t hang quite right from the shoulders. Most people have asymmetrically sloped shoulders, such that one side hangs lower than the other. In bespoke, a tailor can correct for this by adjusting the pattern. But since ready-to-wear is cut from a standard and symmetric pattern, one side will naturally hang lower than the other. With the coat unfastened, this will show up in the form of an uneven hem, which will look like an unbalanced scale. When you fasten the coat, there will be drag lines near the buttoning point. To be sure, the difference here is small, and not likely something anyone would notice in real life. But it does show the benefit of having something custom-made.

The good news is that a ready-to-wear coat can be corrected. An alterations tailor just has to “pick up” the coat from the shoulder seam. This is done by cutting a wedge out of the shoulder line and adjusting the armhole or sleeve to compensate. If you adjusted the RTW Formosa sport coat in this way, the hem would hang evenly and the drag line would disappear. You have to wonder, then, if anyone would be able to tell the difference between these two coats. (Note, the extra shirt cuff you see on the bespoke garment is because the coat is cut to accommodate a watch, which David wasn’t wearing that day).

What about the other supposed benefits? It’s often said than a hand-padded chest is softer, a hand-padded lapel blooms from the coat, and a handsewn armhole allows for a certain elasticity not possible with machine-sewing. But over the years, I’ve found these issues are perhaps a bit more complicated. Bespoke tailors are often limited in what they know because they don’t work in factory production. Factory workers, on the other hand, often don’t know much more than the few steps they manage on the factory line.

A few weeks ago, I talked to Salvatore Ioco of I Sarti Italiani, a bespoke tailor who’s in the unique position of also running a factory. On the issue of padding lapels by hand or machine, Salvo says you can’t really tell the difference until you get down to very lightweight cloths, such as those below 9oz. Even then, the machine is better. “For our bespoke customers, we pad our lapels by hand because our customers prefer it,” he says. “But there are machines nowadays that can stitch a lapel while rolling the fabric on a cylinder, which achieves the same shaping.”

Salvo may be referring to the Strobel KA-ED single-thread roll-padding machine, which is a brilliant piece of German engineering. It stitches a lapel like a typewriter carriage, beginning at the roll line until it reaches the top of the lapel, then stops and moves to the next line down, where it repeats. In an eight-hour workday, a skilled operator can finish up to nine hundred coats in this way, compared to the ten coats a tailor can complete if he or she does them by hand. The process is utterly unromantic (in this video, it almost looks like the person is faxing a document). But it’s effective. Since it costs $100,000 for a pair of these machines, however, it’s only practical in large-scale factories, which means most small workshops aren’t even looking at this kind of technology.

Like Salvo, Robert Jeffery Diduch is another bespoke tailor with extensive factory experience. He’s the Vice President of Technical Design at Hickey Freeman, a part-time pattern-maker at Samuelsohn, and a co-owner of a new made-to-measure company. He says some of the ideas people have about bespoke tailoring are based on old technologies, which have long been outdated. Today, there are machines that can pad a chest just as well as a skilled tailor.

“In a small tailoring shop, you have two or three choices: you can pad a chest by hand, which is soft and easy to shape, or pad it with a regular lockstitch or zigzag machine, which is rather flat and stiff,” he explains. “What a small tailoring shop won’t have, and what a large, quality factory should, is a double-needle jump stitch machine with a rounded, mound-like shape. This allows the operator to shape the layers in the same way we would when hand-padding, and density of the stitches can be controlled to give the same softness. I don’t think anyone could tell the difference just by wearing or observing a finished garment.”

There’s also this often-repeated idea that handset and handsewn sleeves are more comfortable. Since chain-stitching and hand-stitching can loop back on itself, the idea is that hand-sewn seams allow for more support and “give” than a machine-executed lock-stitch. In this way, like the tendons in your shoulder blade, an armhole will stretch where needed when you extend your arms.

But back in 2008, when Diduch tested this theory on a bespoke, handmade suit he tailored for himself, he was surprised to see there wasn’t much stretching along the back of the armhole. “The back of the armhole didn’t touch my body at all,” he wrote on his tailoring blog Tutto Fatto a Mano. “The forward motion of my arm was dragging along the front of the armhole, causing the area shown in yellow to pull. The garment was pulling around my blades, but mostly along the latissimus dorsi. The bias area received no tension, and the area under strain is on the straight grain, so there would be not much give. The front of the armhole, along with a large part of the underarm, is tacked into the canvas, which negates any elasticity.“

When it comes to whether someone can spot a bespoke coat in the wild, the cinch, for me, was hearing that Diduch himself can’t easily see the difference. At a recent charity event, Diduch saw a photographer wearing a very special jacket. It was tailored from a high-quality Dupioni silk, made with handmade buttonholes of the finest quality, featured hand pick stitching, and had pockets that had been shaped by hand, rather than an automatic machine. “All hallmarks of good bespoke, but also something that could have come out of Brioni or Attolini,” Diduch said. “It turned out, he got it at a vintage shop for $6. I told him he got a very good deal and left it at that, but I was tempted to ask for a peek inside the pocket.” You have to wonder: if a bespoke tailor and professional pattern-maker with decades of experience can’t tell the difference between benchmade and high-end RTW, what chance does the average consumer have?

Even just asking whether someone can tell if a coat is bespoke presumes a clear delineation between these systems of production that may not fully represent reality. In the storybook tale of tailoring, these systems are simplified into something like this: Ready-made is what you can readily find off-the-rack. Made-to-measure is a CAD-adjusted block pattern that comes with one fitting. Bespoke, which represents the pinnacle of craft, is when a pattern has been drafted for you from scratch, and it comes with three fittings (the basted, forward, and final).

In reality, these systems are becoming increasingly blurred. Some ready-made garments come with just as much handwork as bespoke. Certain made-to-measure companies will first fit their clients in a try-on suit, which bumps the number of fittings up to two. Some bespoke tailors, including those in and around Savile Row, will also work off of block patterns, although they’ll adjust them by hand. A few will skip to the forward fitting, which puts them at the same number of fittings at some MTM companies. In Naples, there’s a growing number of bespoke businesses that are trying to scale up with something they call “semi-bespoke.” In this system, a tailor will have a set of block patterns, which will be adjusted by hand according to a client’s measurements. The garments are then cut, sewn, and made straight-to-finish. In this way, these suits represent a kind of halfway point between traditional MTM and bespoke.

The main difference between these systems is about how much time can be put into a garment. Factories are about efficiency, so they need clothes to go through the system with as little human intervention as possible. Similarly, a store selling $2,000 MTM suits may not be able to put as much time servicing a customer as one that is selling $5,000 bespoke garments. Consequently, results will depend on how well you already fit into one of the existing block patterns.

A few weeks ago, I was having lunch with some friends, including Edwin Deboise, the founder and cutter at Steed. Edwin was telling me about his experience working with a Japanese factory while trying to set up and refine a made-to-measure program for another company. Since the factory was unwilling to purchase new block patterns, they were limited in terms of what they were able to produce. If a client exceeded the parameters allowed by a certain pattern, the company could either refuse the order or adjust the pattern by hand (which would require the work of a skilled bespoke tailor, whose time could be better spent doing more critical things).

Here’s an example: say a customer has a big stomach. To account for this, a tailor would need to extend the front balance, such that the coat doesn’t look too short. The CAD-adjusted block pattern, however, can only be extended so much before other issues come up. To get the pattern right, you would either need a new block or a skilled bespoke tailor. That, of course, costs times and money, which may not be feasible when a customer is only paying $2,000 for a suit. The limitation of RTW and MTM, then, is about how well a customer fits within a particular block. Notably, Diduch is working a new MTM program that would allow a company to draft a pattern from scratch, which would theatrically break down yet another wall between these systems.

So then, what are the benefits of bespoke? I think there are five:

- Symbolic Value: If you value craft for its own sake, then bespoke is nice because it represents a certain level of human achievement. For people who value tradition, it can also represent a certain Old World way of making things.

- House Style: If you value a tailor’s house style, that may also only be achievable in bespoke. For some reason, I’ve yet to see anyone do those curvy sweeping quarters as well as Liverano.

- Classic Style: To a degree, it’s easier to avoid trends when you go bespoke, assuming you don’t inject a trend into the design yourself. You can get a lapel that’s middle-of-the-road, rather than very wide or thin. You can get a jacket that’s halfway between your collar and the floor, rather than zoot-suit long or very cropped and short. So on and so forth.

- The Tailor’s Advice: More than just providing you with a custom-made garment, a tailor is also someone you can lean on for advice. He or she should be able to recommend cloth, advise you on stylistic details, and most importantly, tell when something fits. Most men have little experience with tailored clothing, so they benefit from having someone with technical expertise be able to judge whether something like the balance is off.

- If You Have a Difficult Figure: Clearly, if you have a difficult-to-fit figure, you will be best served in something custom-made, rather than ready-to-wear.

Assuming you fit well into a block pattern, I don’t think there’s a practical difference between ready-to-wear and bespoke. And yet, for reasons I can’t fully articulate, I still prefer bespoke for my wardrobe. Even with all the hassles, disappointments, frustrations, and potential pitfalls that can come along the way, there’s something so beautiful and romantic about the process. I think of it as an irrational pleasure.

In the mid-18th century, as machines were starting to replace human labor, Denis Diderot edited the remarkable thirty-five-volume book, The Encyclopedia (or Dictionary of Arts and Crafts). The authors pondered on the meaning of traditional, handmade crafts at a time when machines were becoming increasingly sophisticated. Machine-made goods are made perfectly and precisely. As a collection, each piece is indistinguishable from the next. Handmade products, on the other hand, have what the authors of The Encyclopedia called “character.” They’re made with some vision of an ideal in mind, but since they’re created with human hands, there are always slight variations or inconsistencies. By being just slightly off from the ideal, each piece asserts its individuality to the world.

Philosophers such as Voltaire believed that if we could accept and value these qualities in crafts, we could learn something about life itself. It’s concretely human to strive for perfection but fall just a bit short along the way. The pursuit of perfection, Voltaire adjured, would lead men to grief, and leave no room for surprises. By appreciating the irregularities in handmade goods, Voltaire thought we could develop more realistic expectations about life and lead happier existences.

With all the advancements in machine-made production, I asked Diduch if he thought factory-made suits would ever replace benchmade tailoring. “I hope not,” he quickly replied. “I think bespoke occupies a very special place. Think of it like this: would you rather have a perfect machine-made replica of the Mona Lisa or a slightly imperfect handmade replica?” I’m not sure anyone can tell the difference between high-end ready-to-wear and bespoke, but I also don’t think bespoke has to offer practical advantages for it to have value.