In his 1966 essay “The Secret Vice,” originally published in The New York Herald Tribune, the white-clad chronicler of American culture, Tom Wolfe, starts by talking about men who love handmade buttonholes. This was, of course, before surgeon cuffs were standard on ready-to-wear, but the passage will ring true to anyone who’s ever obsessed over the details.

“Real buttonholes. That’s it!” Wolfe exclaimed. “A man can take his thumb and forefinger and unbutton his sleeve at the wrist because this kind of suit has real buttonholes there. […] Yes! The lid was off, and poor old Ross was already hooked on the secret vice of the Big men in New York: custom tailoring and the mania for the marginal differences that go into it. Practically all the most powerful men in New York, especially on Wall Street, the people in investment houses, banks and law firms, the politicians, especially Brooklyn Democrats, for some reason, outstanding dandies, those fellows, the blue-chip culturati, the major museum directors and publishers, the kind who sit in offices with antique textile shades – practically all of these men are fanatical about the marginal differences that go into custom tailoring.”

The phrase “it’s all about the details” has been exhausted, but in classic men’s tailoring, it’s still true. Suits and sport coats follow a template that’s the result of many generations and skilled hands. But there’s still plenty of room for personal expression. Much has been written about pocket styles (jetted, welted, and patched), lapel shape (peak, notch, straight, and bellied), and closure (single button, two-button, three-roll-two, and the never to be worn hard-three). However, there’s not much online about how the edge of a coat can be finished. It’s a detail that’s easy to forget but can make a surprisingly strong impact on how a garment looks. Here’s a run-through:

SINGLE EDGE STITCHING

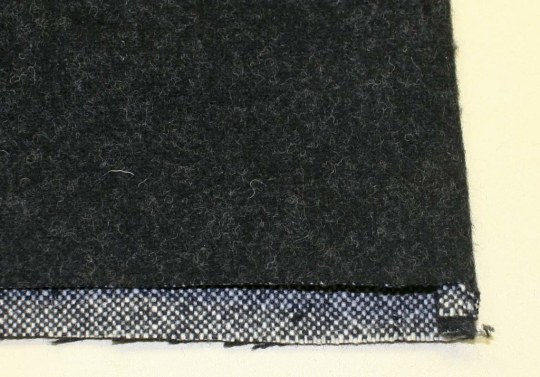

Let’s start with some basics. Since the edge of cut cloth frays, a tailor has to sew a seam away from the edge (this is known as a seam allowance). Once sewn, the fabric is then folded over, like the flapping wings on a bird. Doing so conceals the seam between the two layers, allowing the garment to look more cleanly finished. You can see this in the photo of the double-faced, charcoal cloth above.

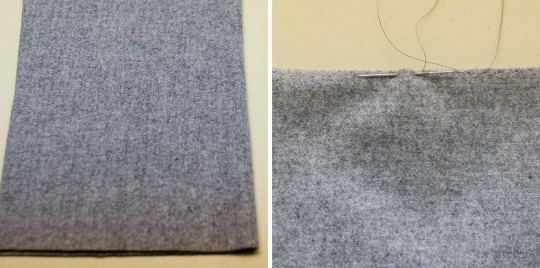

After the fabric has been turned over, the edge is pressed. However, this edge can be distorted over time if exposed to humidity (a good reason to never use garment steamers or hang a suit up in a steamy bathroom). So, to prevent these layers from puffing up, a tailor will sew the outside by hand, compressing the four layers using either a backstitch or running stitch. In factories, this same effect is sometimes imitated using AMF, Complett, or Columbia machines. If the stitch is done with a lockstitch machine (the same type of device used to make the internal seam), then it is known as a single stitch. The photos above are from Jeffery Diduch, who has more info on this on his excellent tailoring blog, Tutto Fatto a Mano.

This edge stitching can be seen above in the Armoury’s photos (shot by Milad Abedi at the last Pitti Uomo). It’s the most common finishing style on tailored clothing, and probably makes up the bulk of garments in your closet. This stitching keeps the edge laying flat and crisp, as well as preventing it from rolling to the wrong side. And since it’s done close to the edge — about 1/16" away — it’s discreet and subtle. For the most part, the seam disappears and becomes part of the edge’s line.

On a handmade suit, particularly fine worsteds, hand picked edge stitching can result in a lovely, artisanal detail: a slight dimpling, which you can see on Taka’s grey suit above. On machine-made garments, however, sometimes this effect is exaggerated and looks … less great. When shopping, be wary of pick stitching that looks like it was executed with a nail gun. Well-executed machine stitching looks better than faux handwork. There’s no shame in good machine-sewing either. Most traditional American suits and sport coats, including those from J. Press, are finished with a lockstitch.

DOUBLE EDGE STITCHING

A double edge stitch is simply two rows of edge stitching. The style is more common in Southern Italy, especially Naples. And while the practical effect is the same – to compress the four layers of fabric so the edge lays flat – the second row is mostly done for bragging rights. It’s a way to make a garment with a higher level of handwork. In Italy, tailors often use a thicker thread, such as silk buttonhole twist, to make the detail look exuberant. I think of it as being a showy, regional detail, like waterfall sleeve heads or overlapping cuff buttons. I also think it’s better on summer garments, such as Simon and Pino’s tan sport coats above, although that’s not a hard rule.

SWELLED EDGE

Finally, we have a swelled edge. Edge stitching is typically done 1/16" away from the edge to keep it discrete. But if you move the stitching a little more inward, towards the end of the seam allowance, it creates what’s known as a swelled edge. Instead of compressing all four layers of fabric, a shifted seam will only hold down two. This encases the two internal layers, puffs them up, and creates a sort of bas-relief effect. Think of how the stitching on a quilted jacket puffs up the batting inside.

When done by a lockstitch machine (a single stitch), the added number of stitches per inch will create a tighter seam, and thus a more pronounced look. You can see this on Mark Cho’s fall cotton suit above. Traditionally, American clothiers — including Brooks Brothers and J. Press — finished some of their fall and winter garments this way. The Armoury’s washed cotton suit this fall has many of those American trad hallmarks: a 3-roll-2 button stance, slightly narrower lapel, and a single stitched, swelled edge

Much like how edge stitching can be done by hand (pick stitched) or machine (lockstitch), the same is true of a swelled edge. If a swelled edge is hand-sewn, the effect is a little more subtle. Steed in London finished Voxsartoria’s Donegal sport coat above with a hand picked, swelled edge. On fabrics that are either very lightweight or spongey, this effect can be harder to spot. I find it’s more apparent with substantial, denser goods, such as hearty tweeds that weigh more than 14oz.

In the photos above, you can see the difference a machine can make. The handsewn swelled seam on the lighter gray flannel is less pronounced, whereas the darker grey flannel (machine-sewn) is more tightly bound and readily apparent.

SO, WHEN TO USE WHAT?

On ready-to-wear and most made-to-measure, these decisions will be made for you. Depending on the garment’s cloth and design, a manufacturer will use the type of edge finishing they feel looks the most coherent. But if you have a chance to choose something for yourself, here are some rules of thumb I follow:

- On formal suits, always get a single row of edge stitching. It’s clean, elegant, and goes with the formality of your outfit.

- On more casual garments, particularly those with a Southern Italian style, consider a double row of hand picked stitching. This detail works better on solid-colored fabrics. On a patterned garment, the stitching can either disappear or make the garment look too busy. Think about the cloth.

- On other casual garments, particularly those made for fall and winter, get a swelled edge. Tweed and corduroy sport coats don’t look right to me without one. The sportier detail helps make a garment look more casual, and goes well with the naturally rustic sensibility of autumn clothing.

- Generally speaking, if your coat has patch pockets, the edges should probably be finished with some kind of casual edge, either double picked or swelled.

That said, a lot of this is up to taste. Steed emailed me yesterday to ask how I want my current order to be finished. It’s a brown summer jacket made from a slubby, wool-silk-linen cloth (pictured below). I went with a swelled edge, mostly because a single row of edge stitching felt too clean to me, while asking for double pick stitching from an English tailor seemed wrong. Go with your gut.