The Talented Mr. Ripley, the film version and not the book, opens with a brilliantly economical line about clothes. Matt Damon, as the film’s anti-hero Tom Ripley, borrows a Princeton jacket from a friend while working as as a piano player at a party. The Ivy League jacket ends up getting him the attention of a wealthy shipbuilder, who thinks that Tom went to Princeton with his son Dickie. He sends Tom away to Europe, hoping Tom can convince his ne’er-do-well son to come back home from southern Italy. Having left his bleak Manhattan life, however, Tom becomes enraptured by Dickie’s charming dilettante lifestyle. So he strikes up a Faustian bargain and steals it. “If I could just go back … if I could rub everything out … starting with myself, starting with borrowing a jacket,” Tom silently dreams to himself at the beginning of the film. And doesn’t Tom’s line neatly sum up what we all wish for when we purchase a new jacket or pair of shoes? The fantasy that it’ll somehow magically transform our mundane lives? (Well, maybe without the murderous crime.)

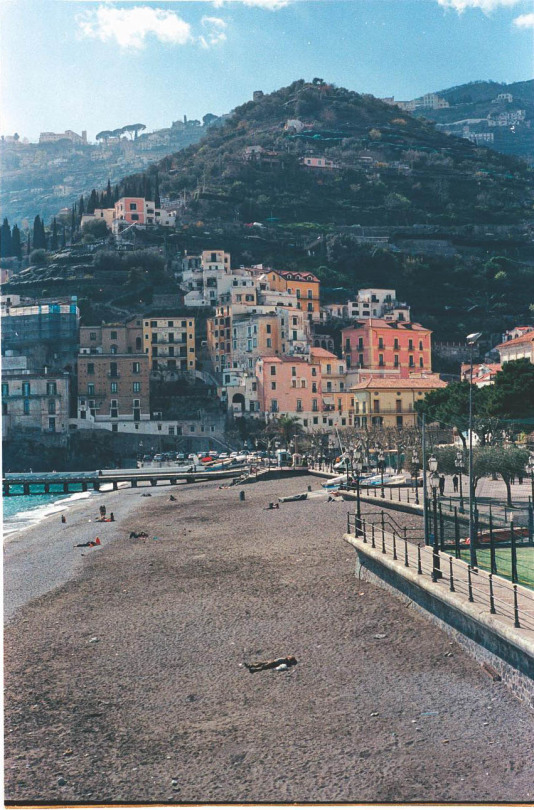

The film is important to fashion in other ways. Every summer, men reference Anthony Minghella’s chilling thriller as one of their favorite sources for warm weather style inspiration. The Talented Mr. Ripley captures the feeling of being young and carefree, not unlike the films of French New Wave, but with more of a la dolce vita vibe and touristy idyllic scenes of a sun-drenched 1950s Italy. It’s a hypnotic, voluptuously beautiful film with tons of references to menswear cliches: inherited wealth, Ivy League education, and an impossibly glamourous lifestyle in an Italian seaside town.

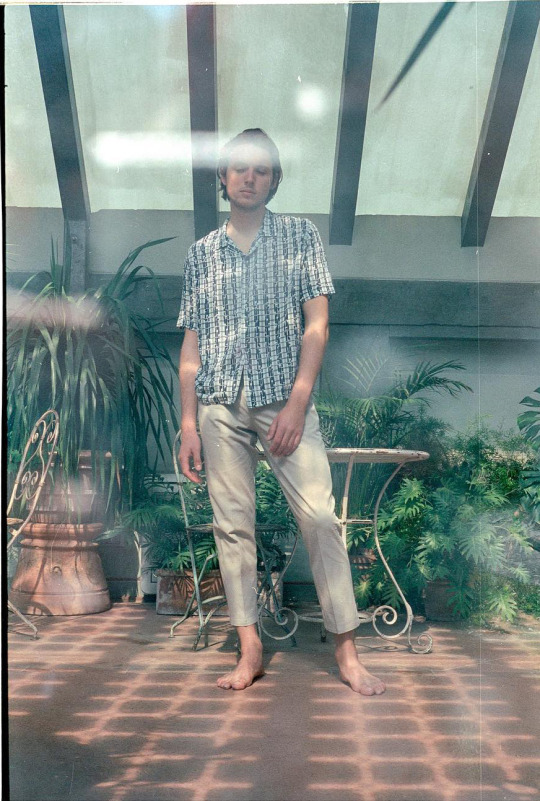

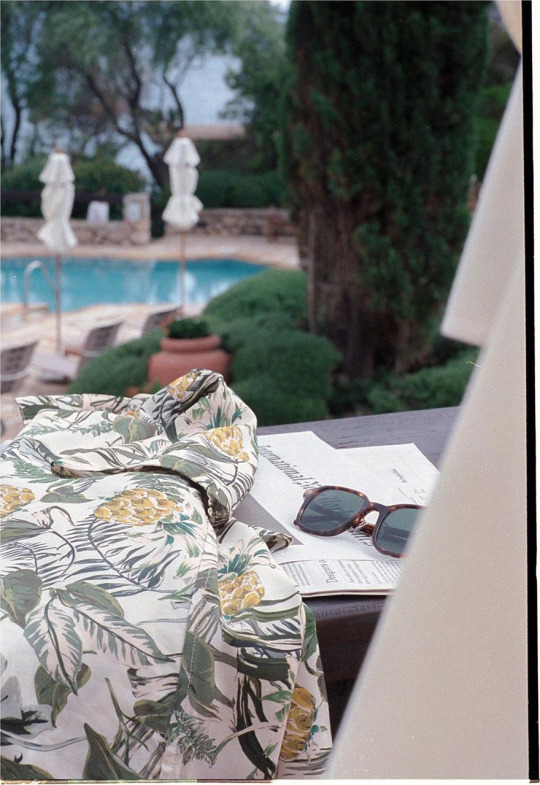

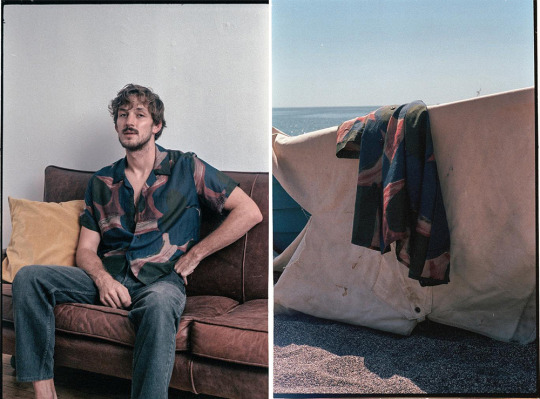

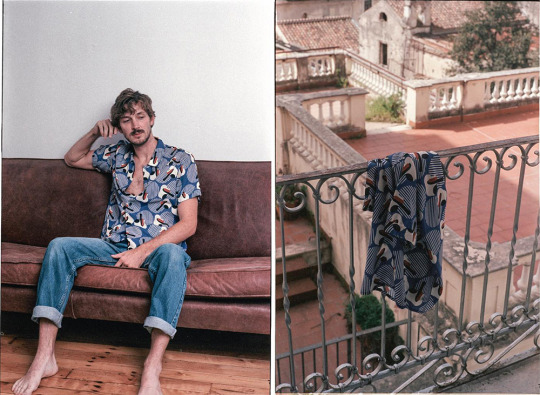

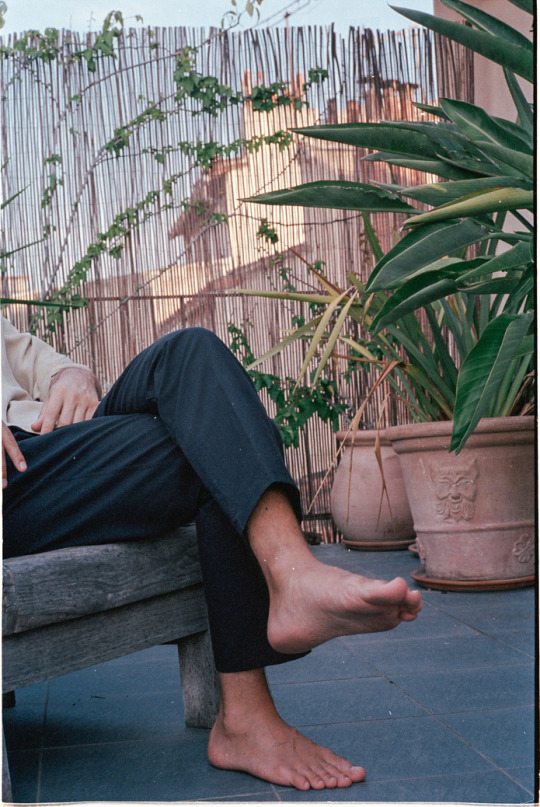

For that Dickie Greenleaf vibe, even if not its literal look, you can turn to Joyce. The relatively new brand offers the same laid-back, vacation style that defines the film. Their clothes are loosely cut, retro-inspired, and pair well with tortoiseshell sunglasses and well-mixed martinis. The company even has the same America-to-Italy backstory. The idea for the brand was first seeded when John Walters, the company’s founder, was working as a product designer in New York. However, it didn’t materialize until Walters visited his girlfriend in Florence, Italy (where they now both live). Today, it’s based out of their Florentine studio, while product fulfillment takes place out of Indian Wells, California. “Stylistically, our online visuals reference a lot of Pink Floyd’s earlier works, as well as some of Alain Delon’s films, such as Purple Noon and The Swimming Pool,” says Walters. “Aside from that, we also get a lot of our style inspiration from traveling.”

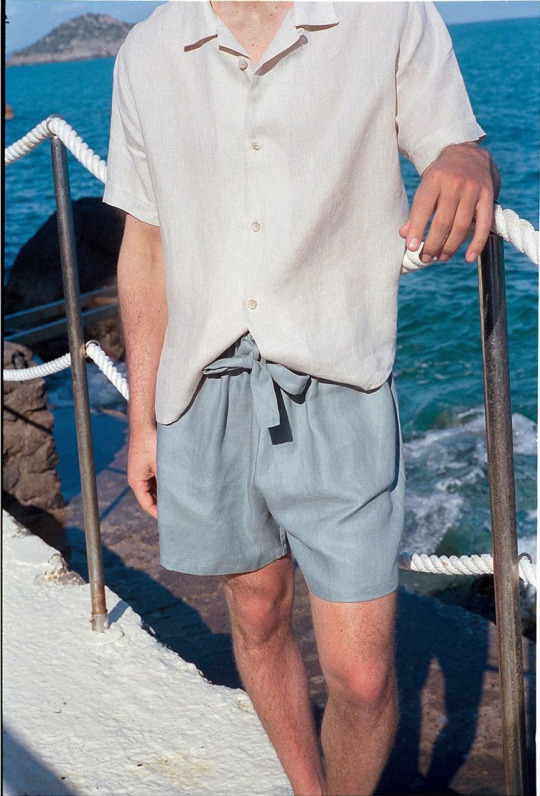

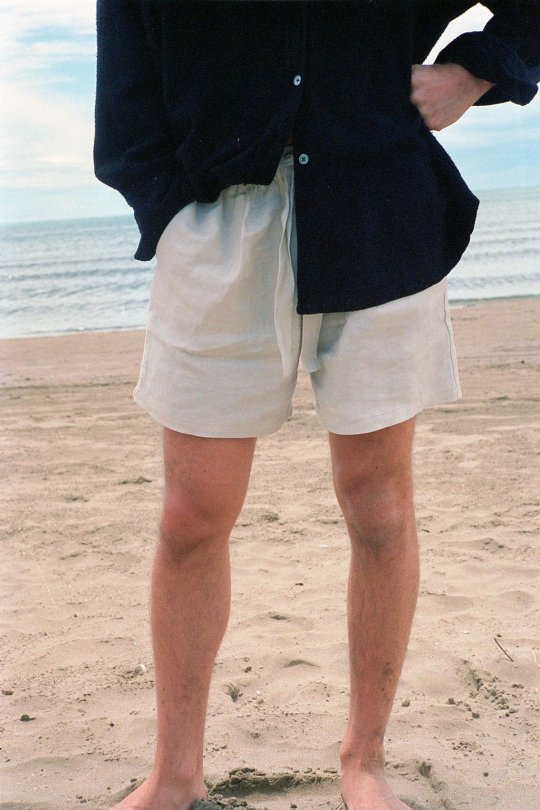

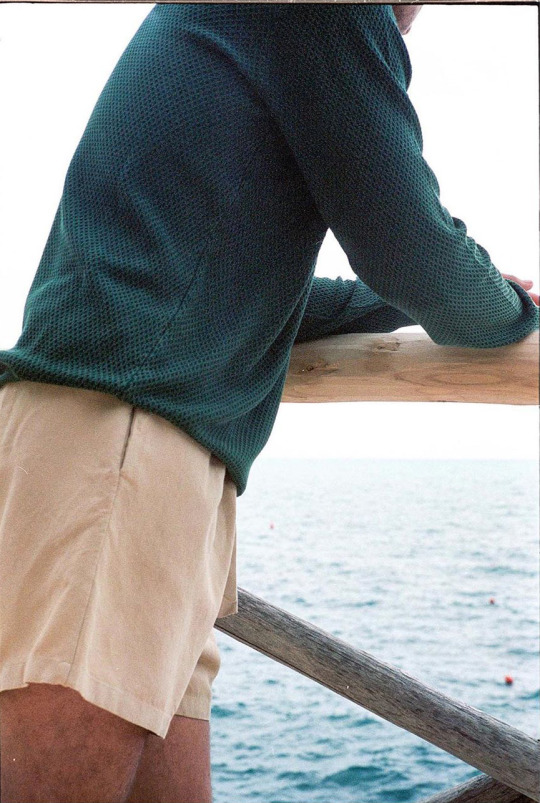

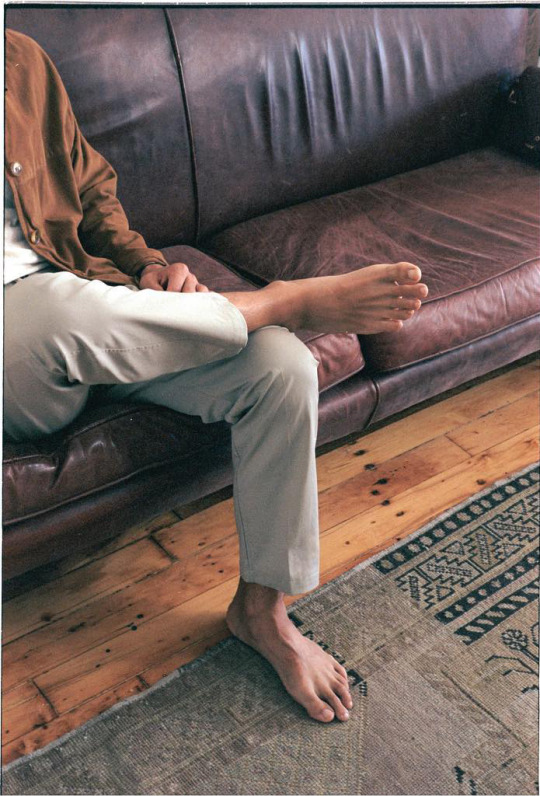

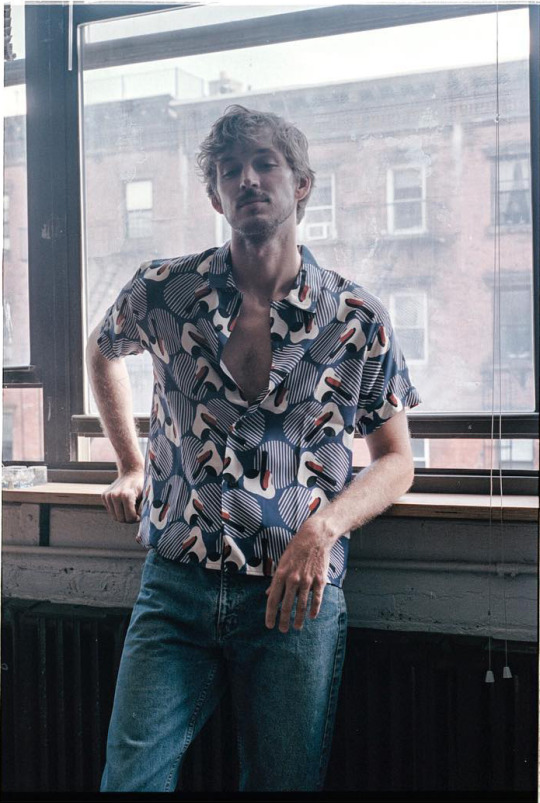

As a brand, Joyce works surprisingly well as a summer uniform. The clothes have just enough detailing to push them away from business casual, but still allow you to wear only a button-up and chinos on hot, humid days. Their lightweight, cotton pants have a slim-straight leg, medium-rise, and subtle, double reverse pleats to give them an old-school Italian sensibility. Their shorts have a tie-waist for style, but both their trousers and shorts are mostly held up using elasticated waistbands. Best of all are the shirts. Made from rayon, silk, and bouncy linens, they look as good as they feel. They’re not strictly contemporary or classic, but have a Dickie Greenleaf style with the color palette of Giorgio Armani.

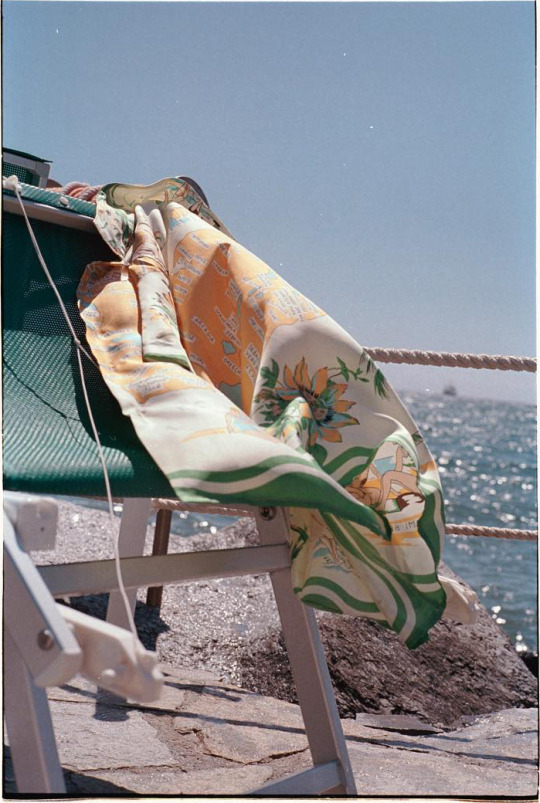

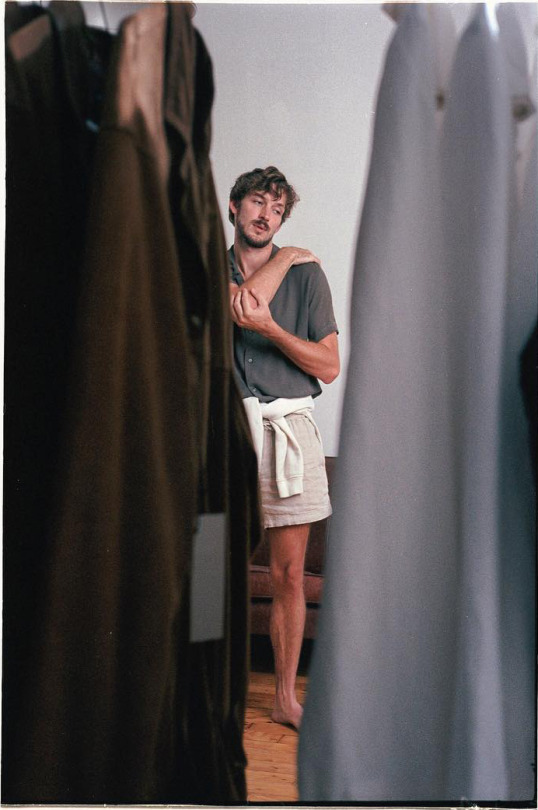

Joyce sources all of their fabrics from jobbers, an industry term for people who sell mill ends, odd lots, and factory seconds. In the textile industry, mills typically run a little more than what a customer orders. So, if a big design house commissions 1,000 meters of a specific cloth, the mill will run 1,100 meters. This way, if there are tiny imperfections, the designer still has 1,000 meters of usable fabric. The unused, excess cloth then ends up in the hands of a jobber, who will resell it to private individuals, fabric stores, and small designers. With a keen eye and a lot of dedication, a designer such as Walters can burrow himself into mountains of fabric at one of these jobber warehouses (pictured above) and emerge with something great.

“There’s an entire industry built on the excess of established houses; it’s quite something,” says Walters. “The fabrics we use range from vintage to overruns. When we source fabrics, we start with a product in mind. Otherwise, it’s easy to get carried away and buy something because of its feel and limited availability. Generally speaking, we seek out raw, natural fabrics in earthy tones.” For summer, that means soft, breathable fabrics, such as lightweight cotton, springy linen, and most of all, rayon.

Rayon is summer’s most magical fiber. Like plastic, it’s a child of the Great Depression, and while its foundation was laid sometime in the 19th century, it didn’t become widely popular until the interwar years. The emergence of rayon coincided with an era in modern art when designers were articulating the meaning of industrial modernity (e.g., Futurism’s glorification of machines and Art Deco’s sleek industrial look). Ezra Pound’s 1934 injunction to “Make It New” would later serve as a shorthand for modernism’s infatuation with all things novel. The interwar period was a time when the public still had faith that technology could serve as a countervailing force against social and economic stagnation. So it’s no surprise that, when marketers introduced rayon as a better and more affordable alternative to silk, people were eager to get with the times.

Rayon is made from mashed-up wood pulp, which has been chemically processed and then extruded through a machine, much like how a chef might make spaghetti. Those strands are then spun into yarns, which in turn are used to make fabrics. Authors of textile books can’t seem to agree whether rayon should be classified as natural because it’s made from regenerated cellulose fibers, or artificial because of its chemical processing. Perhaps it’s both. In any case, rayon is exceedingly comfortable, feels cool to the touch, and typically has soft, silky texture (although, it can also be made to feel like wool, cotton, or linen). “Rayon provides the ideal drape that you can’t achieve with cotton,” Walters explains. “When blended, rayon adds strength to the fabric.”

The downside of rayon is that it can’t be machine washed. Instead, most garment manufacturers recommend you either dry clean or hand wash it. I’ve had success hand washing all my rayon garments in the sink with a bit of sud-less, rinse-free Soak detergent, although anything gentle should do. Rayon also can’t be ironed, as the extreme heat can scorch it, but I find wrinkles naturally fall out within an hour (with the exception of rayons made to feel like linen, for obvious reasons). The good news is that, since rayon doesn’t hold odors as easily as cotton or linen, you can get away with two or three wearings before needing to clean it.

I bought two shirts from Joyce earlier this month. The first is the company’s signature M001, one of their first products, in a deadstock Italian viscose, which has a silky hand. The shirt features a camp collar, relaxed fit, and handpainted design (although that design has been digitally transferred onto the fabric). The shirt goes surprisingly well with 3sixteen’s slim-straight jeans and Yuketen’s woven huaraches. The M005, on the other hand, is a bit more challenging with a wider, cropped silhouette that I find works better as an overshirt than a button-up. That one ultimately got returned, although I can see it working on certain people.

There are some things about their construction I feel could be improved. I wish the shirts featured a single chest pocket, which would be useful on a jacket-less summer uniform. The stitching could also be cleaner, especially on the more slippery rayon shirt. And I found the size tag, which is sewn into the shirt’s interior side-seam, to be a bit itchy against bare skin, although it was easy enough to snip off. That said, the prices are refreshingly affordable in today’s fashion world. Shorts are just $149, chinos are $189, and shirts start at $179. The company also has a reasonable 14-day return window.

Walters tells me that, later this year, the company will debut its first autumn/ winter collection. “It’ll skew more towards the temperate winter climes of Los Angeles or Barcelona,” he explains. “Our production is fairly short-sighted by design, but for now, we’re looking at producing some autumn shirting and unconstructed cashmere coats. As far as materials, we’re exploring virgin wool, viscose blends, cashmere, and raw silk.” For most brands, spring/ summer collections can feel like an afterthought, whereas fall/ winter is where they truly shine. Given how excellent Joyce’s warm-weather clothes look, they’ve set a high bar for themselves.