In March of 1973, when men wore long hair and women sported bell-bottom jeans, The New York Times published an article by pioneering feminist scholar Carolyn Heilbrun. The article, titled “Androgynous World,” is about the persistence of the androgynous ideal. The United States at this time was at a flashpoint. While gender stereotypes were becoming more rigid, fashionistas and feminists were imagining a freer future. About five years earlier, Pierre Cardin and Paco Rabanne conjured up streamlined “Space Age” jumpsuits made from stretchy, synthetic fabrics as a way to imagine a unisex world. Second-wave feminists were also pushing back against the gender stereotypes of the previous decade. Many feminists believed girls were being lured into their subservient roles by first accepting gendered clothing expectations. To be equal to men, they’d dress like them – or, at least, in ways that weren’t traditionally feminine.

“The idea of androgyny apparently takes a little getting used to. First responses tend either toward bewilderment or hostility. The word itself is easily enough defined for the bewildered: comprising the Greek words anthro (male) and gyne (female), it suggests the unity rather than the necessary separation of what we have come to think of as masculine and feminine qualities,” Heilbrun wrote in her article.

“For the hostile, who in some sense feel threatened by this unfamiliar idea, further assurance is required. Androgyny does not mean the loss of all distinctions; those who are terrified by the word probably envision everyone, man and woman, dressed indistinguishably, like members of the Chinese Army. Those who are terrified further assume that in robbing us of clearly delineated sexual models, androgyny will rob us of all order and sanity. If we are to have more than two accepted role models — in youth, the quarterback and the cheerleader, in later life, the corporation manager and the corporation manager’s wife — will we not, in fact, be diving off the edge of an ordered world into the abyss?”

Of course, as Heilbrun notes, “between the quarterback and the cheerleader, we have lost too much of our humanity; we have come close to losing humanity altogether.” In interviews, Hedi Slimane says he created his razor-slim look partly because he didn’t identify with the equally extreme, stony exteriors of Mr. Olympia bodybuilders, a masculine archetype popular in the ‘90s. The received ideas of masculine and feminine clothing don’t just lock people into the confines of gender; they insist on expressions that don’t fully reflect the spectrum of human possibility.

“In an androgynous world, men would be unable to escape their humanity by putting on the aggressive attitudes of maleness; women would be unable to escape theirs by adopting the passive attitudes society has urged on females,” Heilbrun writes. “This seems a small enough price if we can bring humanity, to its salvation, back toward the center of the masculine‐feminine spectrum. We may even discover the gentleness of men, the forcefulness of women, and not be afraid.”

Since the gender revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s, however, only women have really crossed the divide. Today, most clothing websites still operate on a “men’s” and “women’s” navigation menu, and while women occasionally shop in the men’s section — buying menswear in small sizes at Odin, Totokaelo, and Dover Street Market — the reverse rarely happens. At the same time, something interesting is occurring. First, unisex fashion is emerging for the second time. Today, brands such as Lemaire, 69, Telfar, Olderbrother, Smock, and Studio Nicholson are neither strictly masculine nor feminine. Instead, their clothes are just as loose in their identity as their cut. “I would like to see anybody wearing my clothes,” says queer fashion designer Claire Fleury. “And I do mean anybody.”

More women than ever before are also wearing traditional men’s clothing — and they do so in ways that reflect the untrammeled creativity in capital-f fashion, a realm traditionally reserved for them. Even for guys who like traditional men’s style, it’s hard not to notice the number of stylish women in men’s attire, and in doing so, take inspiration on how they can wear clothes in new ways.

Emilie Casiez, a designer at Nigel Cabourn, is a perfect example. Born and raised in Paris, she grew up in a multi-cultural family with deep roots in the clothing trade. Her French great-grandmother had a lace factory in the north of France; her Japanese mother worked for Maison Grès, a leading French couturier for her generation. When Casiez was just fourteen years old, she attended her first fashion show with the accompaniment of her mother. The show impressed her so much, she decided that night that she’d pursue a career in the rag trade. Casiez went on to study fashion design at Studio Berçot, a private training institute in Paris, and then started her eponymous label during her second year of college. And while her company made clothes for both men and women, the women’s side of her Haut Marais boutique stocked traditionally femme clothes — delicate wool cardigans, thigh-length dresses, and jersey tops with cute, whimsical drawings.

Fifteen years later, Casiez’s wardrobe looks very different. After having moved to Japan to work for Tsumori Chisato, another traditionally femme label, Casiez met the British designer Nigel Cabourn, who’s known for his vintage-inspired workwear and expedition gear. The two struck up a friendship and started going to flea markets together whenever they happened to be in the same city. At some point, Cabourn asked Casiez how she would envision a womenswear collection under his label — so she sketched out a few designs. “I was really inspired by the challenge and felt I could add a feminine, modern touch to the women’s collection,” she tells me. “Nigel loved the drawings, and we realized we had the same vision for the women’s line.”

Today, Casiez works for Nigel Cabourn, designing the company’s Lybro and Authentic Woman’s collections, as well as some of the mainline pieces produced in Japan. Nigel Cabourn’s Lybro, a reinvigoration of classic British workwear brand Lybro (established 1927), channels the practical details of traditional workwear, such as chore coats and coveralls rendered in heavy Japanese denim. On someone feminine, their unisex, pomegranate-colored “Frankie’s shirt” looks like a dainty, floral button-up. On someone masculine, it’s a Brazillian surf shirt. On someone androgynous, it could be the swinging, psychedelic style of London’s Granny Takes a Trip.

Nigel Cabourn also has a “proper” womenswear collection under their Authentic label, but its masculine edges are unmistakable. “Nigel and I start with a concept every season, and then we hunt for vintage pieces that fit that theme,” Casiez explains. “Then I find the fabrics and work with our patternmakers to create the silhouettes I want. So while the two lines stem from the same concepts, the womenswear collection is interpreted in a way to create feminine outfits that go along with our menswear collection.”

Nigel Cabourn’s Lybro and Authentic Woman’s lines show that gender expression in fashion doesn’t follow a straight line. Instead of eliminating gender signals entirely, androgynous fashion often combines masculine and feminine elements in a way that’s playful, which in turn makes the wearer’s gender glaringly obvious. This tradition has a rich history with figures such as Diane Keaton in the 1977 film Annie Hall, or how female punks and grunge musicians thrifted the same lumberjack flannels and combat boots as their male counterparts in the ‘90s.

Jo Paoletti, a Professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland, describes this as “sexy androgyny.” “Part of the appeal of adult unisex fashion was the sexy contrast between the wearer and the clothes, which actually called attention to the male or female body,” she writes in her book Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution. It’s not just women, either. Some of the most famous examples of androgyny include the kings of rock royalty — the sequins-and-high-heels-wearing likes of Prince, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, who were once the sex symbols of heterosexual masculinity.

At the same time, one of the first “out” gay male subcultures was the Castro Clone. Men who grew up with the idea that being gay necessarily meant being effeminate looked toward the traditional images of rugged masculinity for a new identity. Castro Clones dressed with the care of Edwardian dandies, but the look was cowboy or bushy workman: tight blue jeans, plaid shirts, leather vests or bomber jackets, and boots. “In the 1970s, gays were much more visible and less concerned about being recognized as gay,” Max Mosher wrote in “Out of the Closet.” “Clones had taken the look of the working-class male and sexualized it, emphasizing muscles through tight t-shirts, and shapely buttocks through deliberately shrunken jeans.”

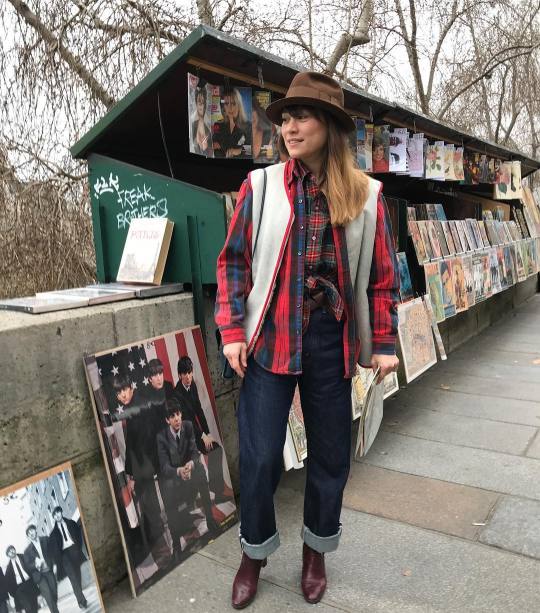

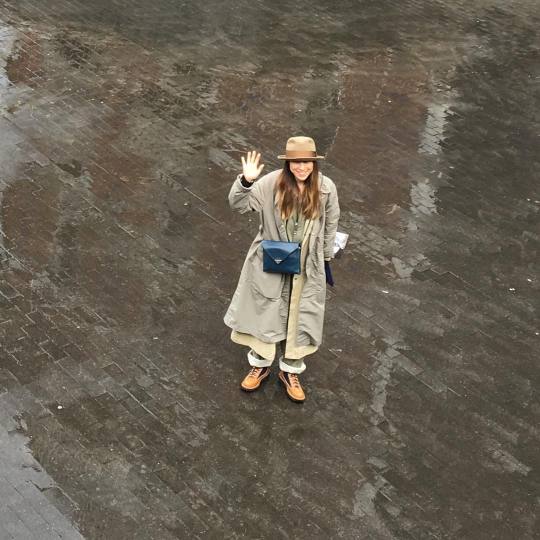

This soupy mix of androgynous dress history shows how clothes can be worn in complex ways to communicate different messages. Nigel Cabourn Woman’s Instagram account is full of examples of how masculine attire can be worn in a feminine manner. And, closing the loop, it’s a treasure trove of menswear inspiration. Casiez’s feminine style shows masculine men how they can wear workwear in new ways. In the photo above, she sports a cropped, off-the-shoulder jacket with slim-straight jeans and visually heavy shoes — a silhouette that works on either men or women. In many of the photos below, she combines wide, high-waisted pants with extra-long coats, as well as jumpsuits with heavy-duty outerwear. “I like to wear matching colors, such as pulling a color through in a hat or cap,” she says. “For example, I love wearing a denim outfit from head-to-toe, and mixing vintage pieces with our Mainline and Lybro clothing.”

Being a designer for Nigel Cabourn, Casiez is constantly referencing vintage workwear. “Vintage is a big inspiration for us, and we’re always looking for rare workwear pieces from the 1930s through to the ‘60s,” she says. “I live in Paris, but Nigel and I often meet in London to go to Spitalfields Market, Shoreditch vintage stores, or even war museums to research for a collection. We’ve gone to the Polish Army Museum in Warsaw and Airborne Assault Museum in England. I’ve seen so many crazy pieces in vintage archives. One of the more recent things includes an electrically heated, flight suit liner with matching gloves and sleepers, which was worn by the Royal Air Force in WW2.”

An inveterate thrifter, Casiez has an enviable collection of vintage clothing. Among her favorites is a US baseball jacket from the 1950s. “It has thick, white leather sleeves and a black wool body with red and beige striped ribs. It’s a bit big on me, and the leather is cracked in some places, but that’s what makes it cool,” she says. “I also have a 1940s Land Army stone dress, which I believe was adapted from a piece of workwear around the same period. It has a fitted top, big, pleated sleeves, and an A-line shaped skirt that make it very stylish and wearable. And I love my Swiss Army camo raincoat, which I bought at Spitalfields Market in London. It was apparently once owned by someone who worked on the film Star Wars.”

For a bit of Casiez-inspired style in your wardrobe, start with Nigel Cabourn’s outerwear (brands such as Chimala, Orslow, and RRL are great accompaniments). An oversized coat — either loose and long, or cropped and wide — can look great with slim-straight jeans. You can also try denim alternatives, such as olive fatigues, Carhartt double-knee pants, and workwear styled chinos. Cuff your pants a little higher if you’re wearing chunky boots or high-top sneakers (Casiez often wears Nigel Cabourn’s collaboration with Mihara Yasuhiro, although you can get a similar effect through Chuck Taylor 70s). Casiez’s outfits work because they stay within a theme, but her style also has a strong direction because she knows how to play around with the cut and details of her clothes. When I ask if she has tips on how to wear wide-legged pants, a challenging silhouette, she says: “If you look at how Nigel and I wear it, I think it says it all!”

For more of Emilie Casiez and Nigel Cabourn Woman, follow them on Instagram.