A few years ago, inspired by a photo of Bruce Boyer and an old Mister Crew post, I bought my first hat. It was Lock & Company’s Rambler, a soft trilby that can be rolled up and subsequently stuffed into a pocket. The style is a little more modern and casual than traditional headwear, but upon receiving it, I wasn’t sure how it should be worn. Should it be tilted forward or back? To the side? Can I wear it without looking like a neckbeard? None of the online guides I found helped. No matter what I did, putting this foreign object on my head felt like I was wearing a neon-sign that invited ridicule.

Over the years, I’ve occasionally worn the hat out of necessity: when I’m running out the door and don’t have time to style my hair, or when the Teflon-treated, water-resistant wool promises to give protection from the rain. Eventually, I grew used to it. I can’t say I wear it as well as Bruce, but it no longer feels awkward or unusual. It is, simply, my hat.

Social psychologists call this the spotlight effect, which is our tendency to overestimate how much other people notice our actions or appearance. This peculiar anxiety is captured in the single most common question guys ask when they’re starting to build a better wardrobe: “how can I dress well without standing out?” Whether you’re in Rick Owens or Rubinacci, techwear or tailoring, there’s no way to wear anything exciting nowadays without, in some way, looking different from others. Among men who wear sport coats, no experience unites like having to hear someone ask: “why are you so dressed up?” (Tip: tell them you’re going to see your parole officer for a murder conviction. They’ll never ask you again).

The spotlight effect has been studied for decades, but the most commonly cited paper was published 19 years ago in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. The three researchers — Gilovich, Medvec, and Savitsky — set up a simple experiment at Cornell University, where they convinced a hundred undergraduates to participate in a survey for extra credit. The students were broken into groups and told to meet at a specific time and location. Unbeknownst to them, one student from each group was randomly selected to be the “target participant” (i.e., the real person being studied).

Students were told to arrive at a particular psychology lab, where the experimenters placed a long table in the middle of the room. Since the chairs were only put on one side of the table, they all faced the doorway. As the group poured in, they were asked to take a seat and fill out a questionnaire while one of the experimenters sat idly by. Meanwhile, the target was given the wrong time and location. When they arrived, they were told the location had changed and they had to hurry over to the other site. But first, they had to “put on this t-shirt.” The shirt had a ginormous, body-covering print of Barry Manilow’s neck and face. In their paper, the experimenters assured readers that Barry Manilow is “not terribly popular among college students.” Nevertheless, reluctant as they may have been, and perhaps in dire need of extra credit, all the targets donned the shirt.

Put yourself in that student’s shoes (or, rather, their t-shirt). You’re walking down the hall in this nasty thing, go to the other room, and open the door. You see this long table in the middle of the room and a row of silent students looking up at you. Awkwardly, you make your way to the table and try to find a seat (“oh, I’m sorry, is this your backpack?”). After you sit down and begin to take the survey, the experimenter tells you the others are too far along and it’s best that you wait outside. Great, more social embarrassment. As you get up, a creaky university chair scrapes the floor, making that nails-on-chalkboard sound. You gather your things and awkwardly walk out, confident everyone saw you in this stupid Barry Manilow t-shirt.

This is the long lead-up to the experiment’s real survey. Once the target has left the room, a third experimenter emerges and asks the student: “how many people in that room do you think can identify your t-shirt?” On average, people estimated half the room could remember the embarrassing visage that graced their body. But, when surveyed, only about 25% of people did. Which, just goes to show, people vastly overestimate how much others notice their appearance.

There’s a wrinkle to this story. In another experiment, where researchers gave the target some time to get used to wearing their embarrassing pop-culture apparel, the targets weren’t as susceptible to the spotlight effect. Which perhaps explains why the people most self-conscious about dressing up are those who are just starting to build a better wardrobe — or why I got used to wearing that Rambler hat.

What causes the spotlight effect? Social psychologists think it’s the result of a few things. One is egocentric bias, which is people’s tendency to believe that the world revolves around them (which is obviously false because the world revolves around me). The other is the false-consensus effect, which is when we overestimate how much others share our beliefs. If you’re focused on your embarrassing t-shirt, then, of course, others must be focused on it as well. A third and related concept is anchoring, which is when people use their internal feelings as a reference point to explain the world around them. People overestimate the extent to which their anxiety is evident to onlookers and, conversely, how much they can correctly recognize other people’s feelings. In other words, the spotlight effect makes you feel like there’s a spotlight on you because you’re self-obsessing. But ironically, others are too self-obsessed to notice you.

The spotlight effect helps explain some of the anxieties men have about clothes. It explains why men worry about dressing up in business casual environments, looking overly fashion forward, or trying something they feel isn’t “authentically” them (out of fear that others will think they look foolish). It explains all the weird rules men use to give themselves permission to wear something (e.g. “bracelets are OK if they were given to you by your daughter”). It explains why so many brands, such as UnTuckIt, are less about making guys feel good and more about assuaging their fears that they look stupid or out of place. Ultimately, all these anxieties stem from us overestimating how much others notice or even care about how we dress.

A few years ago, I interviewed a reader named Andy, a Silicon Valley software developer who doesn’t mind wearing suits when everyone at his office is in jeans and t-shirts. He’s also happy to wear beautifully tailored dinner suits for the very normal activity of getting dinner. “If my wife and I go out in the evening, these days we ‘dress up’ because we want to,” he said. “It bothers us not at all if we are dressed more formally than everyone around us. We dress for ourselves and each other, and that’s it. We have reached a point in our lives where it is time to be ourselves. If we find ourselves in a place where everyone else is in jeans, so be it.”

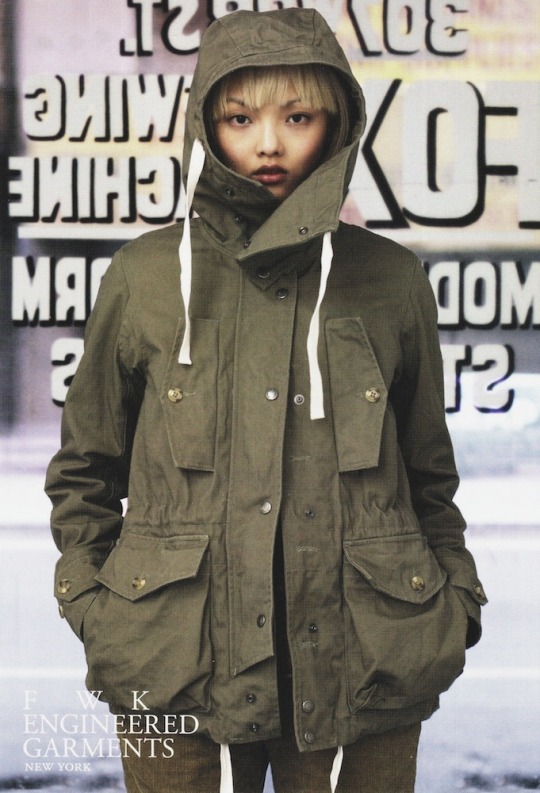

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned it’s OK to dress differently from other people. There are some obvious exceptions — weddings, funerals, and highly conservative offices have specific protocols — but ultimately, clothes should make you happy. Use Marie Kondo’s decluttering method for your acquiring – hold an outfit up and ask if it brings you joy. Wear a casual linen suit, a black double rider, or some weird Japanese brand if it makes you feel awesome. Take Tyler the Creator’s advice and just try stuff on. If you’re a little anxious about an item, wear it around the house for a while and let it “settle in.” For better or worse, people will judge you by the quality of your character, not your clothes, so you may as well use style to enrich your life.