In The New York Times last month, writer Megan Nolan asked the simple question: why do we all have to be beautiful? As a young girl growing up in Ireland, Nolan wanted to be beautiful so badly, she could taste it (“it tasted like blood”). She didn’t want to be cute or pretty. She didn’t want to be more desirable to men. She wanted to be beautiful because it’s harder to make beautiful people look foolish. Their lives are always well-ordered and they never feel embarrassed. And like all teens, Nolan often felt embarrassed.

Nolan’s hard, painful desire to look beautiful has stayed with her most of her life, but she asks at the end of her essay whether today’s inclusive message of beauty — where we’re told everyone is, in fact, beautiful — does more harm than good. “I tried to love myself as I got older, tried to look with clear eyes at my physical flaws and not just accept but admire them. I tried to believe that, actually, I was beautiful, because everyone was, not just the chosen few,” she writes. “I tried forcing myself to concede this, through a fake smile and gritted teeth. I’ve said it aloud, as advised by body-confidence self-help gurus, while looking at myself naked. It’s always felt absurd. […] Wouldn’t it be freeing to admit that most people are not beautiful? What if we stopped prioritizing pleasing aesthetics above so much else? I wonder what it would be like to grow up in a world where being beautiful is not seen as a necessity, but instead a nice thing some people are born with and some people aren’t, like a talent for swimming, or playing the piano. Everyone is beautiful, we’re told. But why should we have to be?”

Men don’t face nearly the same pressures as women to look attractive. We have other ways of climbing up the social ladder — humor, wealth, and even a reputation for violence. This masculine advantage is well-captured in Biggie’s “One More Chance,” where he raps: “Heartthrob never, black and ugly as ever/ However, I stay Coogi down to the socks/ Rings and watch filled with rocks/ And my jam knocks.” As Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in The Atlantic, the word “however” has never been used to greater effect. “There was no ‘however’ for a girl deemed ‘black and ugly,” he writes. “There were no female analogues to Biggie. ‘However’ was a bright line dividing the limited social rights of women from the relatively expansive social rights of men.”

Yet, men still face some pressure to conform to classical notions of handsomeness. The reasons are obvious. Social scientists have long recognized there’s an attractiveness premium (or, conversely, an ugliness penalty). We’re told attractive lawyers and businessmen make more money than their average-looking counterparts. Beautiful people are more often seen as persuasive. Political scientists have also examined the halo effect attractiveness can have on elections.

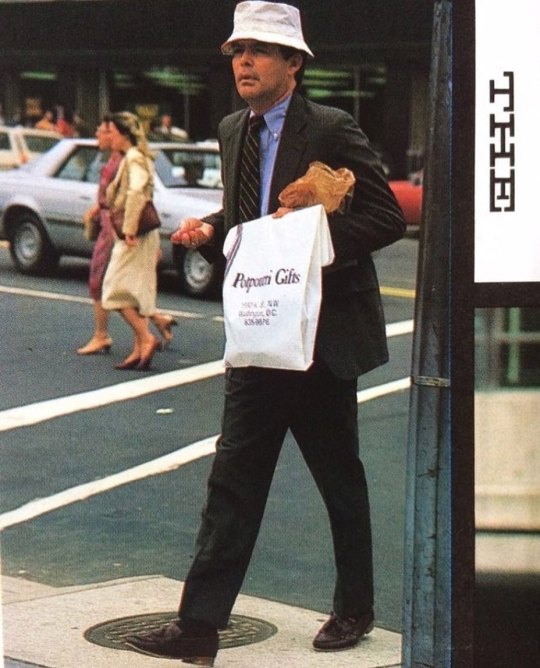

In 2016, the journal Political Behavior published a study on Californian Congressman Henry Waxman. Over the last forty years, Waxman has been a champion of liberal causes, co-sponsoring some six-hundred pieces of legislation and chairing two powerful committees. For his first nineteen elections, he won his seat handily with more than 60% of the popular vote. But in 2012, he narrowly eeked out a victory, defeating his main rival, the independent Bill Bloomfield, by just two percentage points. The results can be taken at face value. According to UC Berkeley political scientist Gabriel Lenz, who co-authored the study, Waxman “suffers from considerable appearance disadvantage.” Lenz and his co-authors showed that, had the ballot shown Waxman’s face, he could have lost as many as ten percentage points, enough to tip the election to Bloomfield’s favor.

Much of this effect boils down to our tendency to equate appearance with character. “Virtue beautifies, and vice renders a man ugly,” 18th-century Swiss philosopher and physiognomist Johann Kaspar Lavater wrote. In his autobiography, Charles Darwin confessed that the captain of the HMS Beagle almost barred him from boarding because, “an ardent disciple of Lavater, [the captain] doubted whether anyone with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage.” A century later, Darwin-inspired eugenicists supported sterilizing people with certain physiognomic traits, which they linked to morality and larger social ills.

In his book Ugliness: A Cultural History, historian Gretchen Henderson documents the rise of “ugly clubs” across 19th-century Western Europe, where ugly bachelors met up to sing, drink, and satirize their own looks. One such club, called The Liverpool Ugly Face Clubb, had ten men. Each member was voted into the club based on whether he had “something odd, remarkable, droll, or out of the way in his phiz.” William Long, for example, was accepted into the club because he had a nose “like a pair of nutcrackers.” Matthew Strong had “flook mouth” and an “irregular bad set of teeth like those of an old worn-out comb thoroughly begrim’d.” Of all the members, Jos Farmer was probably the ugliest. At the end of his long list of qualifications, members of the Liverpool Ugly Face Clubb noted on his record: “His looks upon the whole are extraordinary, haggard, odd, comic, and out of y’ way. In short, he possessed of every extraordinary qualification to rend him Phoenix of Society, as the like won’t appear again this 1,000 years.

To be sure, the attractiveness premium isn’t as simple as it’s commonly presented. According to a recent study in the Journal of Business Psychology, attractive people earn more money, but only if you don’t control for intelligence, health, and personality. In some fields, there may even be an ugliness premium. A few years ago, a University of Essex doctoral student gathered some two hundred headshots of scientists, then had subjects rate those photos according to attractiveness and intelligence. She found that, while people were more interested in attractive scientists, they assumed uglier ones were more capable of doing high-quality work. (Amusingly, when I was in grad school, a difficult math question came up during a seminar and the entire class, including the professor, turned to me for the answer. I am not good at math).

Fashion hasn’t been interested in traditional notions of beauty for a while. Martin Margiela’s mud-dipped shoes and Vivian Westwood’s carefully deconstructed clothes are more mainstream than ever, and yet, traditional ideas of “goodness” persist. Today we have ugly dad sneakers, ugly jackets, and ugly fanny packs (sorry, I mean cross body bags). The most iconic accessory of our time, the MAGA hat, is hideous not just in its message, but also its form. “Do Trump supporters know their hats are ugly? I think they do,” Katy Kelleher writes in The Paris Review. “I think the offensiveness – the bright, flat color; the bad kerning; the made-in-China-ness; the uncaring hypocrisy – is the point. It’s trolling, plain and simple, and it’s a far more influential form than high fashion’s tragically niche designs.”

But today’s ugly fashion isn’t really about ugliness. If it were, we wouldn’t need a million guides on which are the right ugly sneakers to buy, how to correctly wear unflattering silhouettes, and how to wear Teva-style sandals that look “more urban chic rather than granola crunchy.” Kelleher continues: “Equally common is the quizzical coverage, the ‘Why Is Fashion So Ugly?’ articles, and the explainers, which often read like this one from Harper’s Bazaar Australia – it posits that we’re ‘a bunch of hyper-aware Hypebeasts’ obsessed with peacocking. The fashion critic Robin Givhan at The Washington Post argues that the recent glut of ugly trends – prairie dresses, fanny packs, orthopedic sandals, et cetera – are ‘aesthetic provocation’ designed to agitate. ‘The gateway to ugly … was the Birkenstock,’ Givhan writes, calling the German sandal ‘an exemplar of the rise of anti-fashion.’” Except, anti-fashion today is just fashion. The populist backlash against traditional aesthetics was supposed to free us from the tyranny of the beautiful, but now “We the People are just trolling ourselves.”

There’s something special, however, about giving up on the idea of looking correct, proper, or even traditionally handsome. For one, ugliness is low maintenance. You don’t have to starch, iron, or press. Clothes can be just thrown on, and in certain instances, not even repaired. Secondly, ugliness is inevitable. Should we be so fortunate, we all become ugly eventually — some of us just got here sooner than others, and are thus used to it. Perhaps most importantly, ugliness can be a form of timeless style. In the last year of the 19th century, The Sunday Evening Post published an article by political economist Robert Ellis Thompson. The article, titled “The Folly of False Contentment,” was one of the earliest calls against modern consumer culture. “It is a benefit to spread discontent with ugliness in dress, house, and furniture,” he wrote. The inimitable Oscar Wilde put is simpler when he said: “Fashion is a form of ugliness so intolerable that we have to alter it every six months.”

Like Nolan, I’ve given up on the idea that I can ever be classically attractive. To be honest, style icons such as Cary Grant and Steve McQueen have never appealed to me — give me the ill-proportioned Jacques Brel, craggily years of Pablo Piccaso, scruffiness of Georges Braque, and pressed dull-boy look of Bill Evans. I’ve also found that certain clothes are only meant for handsome people, while others are better suited to misshapen gargoyles like me. A short, incomplete list:

- Beautiful Clothes: thoroughly deconstructed tailoring without any haircloth, canvas, or padding; Gucci horse bit loafers; extra-slim-fit anything; nautical striped Breton shirts; shorts; ribbon belts; bright colored pants; Loro Piana; low-slung and hip-hugging pants; fashionably correct ugly clothing; Hedi Slimane anything; most Italian casualwear; dress shirts with tiny collars; and Baudoin and Lange slippers.

- Ugly Clothes: soft, but slightly padded tailoring that helps build a V-shaped silhouette; the drape cut; “old man” shoes; “old man” topcoats; unlined oxford button-down collars; wool gabardine, cavalry twill, and tweed; Norwegian split toes; wide pants (controversial, but I’m sticking this here); Alden’s orthopedic lasts; Engineered Garments; Kapital; most offbeat Japanese workwear; Rick Owens; trad but not preppy; LL Bean duck boots; cargo pants; ripped and repaired raw denim jeans; retro-styled hiking/ outdoor clothes; backpacks; homely Shetland sweaters; stuffy rep ties; and authentic vintage.

Find your ugly style and embrace it. Good ugliness has a sense of nonchalance – an indifference to others and a sense of humor. Like the men in the Liverpool Ugly Face Clubb, it’s about being able to laugh at yourself. It’s less about achieving the perfect, wrinkle-free, on-trend fit, and more about having fun with your clothes. It’s joyful and absurd. It frees you from an impossible game. When people say your outfit is ugly, you can say “yes, thank you!” The best part of having an ugly face or body? When people like your fit pics, you know they’re only doing it because of your clothes.