In the spring of 2010, the U.K.’s Advertising Standards Authority banned two Louis Vuitton print advertisements because they suggested the company’s products were handmade, when in fact they were not. The ads showed two softly illuminated women acting as master artisans (they were oddly in their mid-20s, by the way). In one image, a women is pictured saddle stitching a bag’s handle, while in another, a woman makes a fold on a wallet. Underneath, the copy reads: “A needle, linen thread, beeswax and infinite patience protect each overstitch from humidity and the passage of time […] With so much attention lavished on every one, should we only call them details?” The other says, “What secret little gestures do our craftsmen discreetly pass on? Let’s allow these mysteries to hang in the air. Time will provide the answers.” The images strangely looked like Johannes Vermeer’s paintings from the 17th century. They felt quiet and serene, and evoked a sense of old European craftsmanship that Louis Vuitton would have you believe goes into their mass-market bags.

On the one hand, these might not seem too different from ads with Photoshopped models and carefully staged settings. On the other hand, the issue of craftsmanship is much more tangible than brand imaging. People consciously make decisions on whether they’ll purchase something based on how it was made, and it’s commonly believed that handcrafted goods are better made than machined ones.

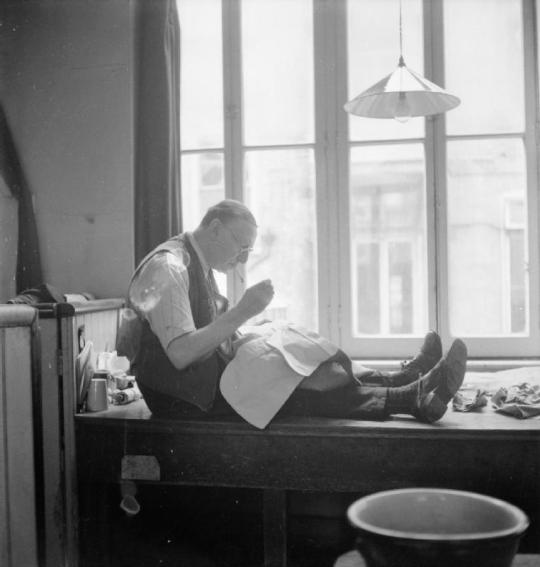

Is there something special about handmade goods, however? Many have thought so. The signs of handwork are a craftsman’s fingerprints, and people have valued craftsmen at different times for different reasons. Greeks and Romans thought of human labor as heroic. Hesiod’s Works and Days and Virgil’s Georgics, for example, portrayed human labor as divine and glorious. Additionally, painters in the 17th and 18th centuries often depicted people finding quiet satisfaction in their labor, and thinkers during the Enlightenment saw craftsmen as emblems of human individuality. Manual labor was placed as being equal to mental labors, and useful work was thought to be the driver of human progress.

When machines began taking a more prominent role in production, traditionalists didn’t reject technology, but rather used it as a way to reflect on what it meant to be human. For example, in the mid-18th century, Denis Diderot, pictured above, edited a remarkable thirty-five-volume book, titled The Encyclopedia (or Dictionary of Arts and Crafts). In this series, writers saw the potential for machines to liberate men. For example, the papermaking trade at the time involved noxious and unsanitary processes. It was thought that machines could be used to remove the bestial tasks and leave humans to do more interesting, intellectual labors. Through technology, men could fulfill their greater potentials. (A similar argument is made today in industrializing economies).

At the turn of the 19th century, however, the industrial age began to crystallize and it became obvious the relationship between labor and technology was not so benign. Machines were replacing workers, and craftsmen were faced with either deskilling or unemployment. Consequently, a resistance grew against machine-driven production. In England, textile weavers smashed mechanized looms in protest. Among their supporters was Lord Byron, who made his maiden speech in The House of Lords defending the frame-breaking rioters. In France, an inventor named Barthélemy Thimonnier came up with one of the first models of the mechanized sewing machine. In 1841, he was contracted to make army clothing in a Paris factory, but a mob of tailors broke in and smashed his machines out of fear they’d lose their jobs.

Later in the century, John Ruskin emerged as one of Europe’s most impassioned critics of industrialization and wrote moral and political arguments about the displaced role of artisans and craftsmen. For him, industrial production was inhuman in every sense of the word. Its productions lacked soul and character, and its organization broke basic human bonds. He considered the hand-built, rough-hewn medieval buildings in Italy, for example, to be more beautiful than the smoothed-over factories taking over England. He also believed the industrial division of labor not only robbed workers of their dignity, but was deleterious to notions of community and citizenship. His writings, which originally appeared in Cornhill Magazine, but later published in Unto This Last, influenced an entire generation of philosophers and artisans, including William Morris, who would later start Britain’s Arts and Crafts Movement.

All of these views left important impressions on our modern attitudes. In the mid-20th century, Greek and Roman ideals of human labor could be seen in communist and fascist propaganda. In more contemporary times, Ruskin’s philosophy has gone through a revival. Machine-made goods are commonly associated with everything bad about the modern world – wasteful lifestyles, unrestrained and intemperate consumerism, and unseen, dark, satanic mills working in the background to support it all (now said to be Chinese sweatshops). As a consequence, there is a renewed interest in craftsmanship and more “humanist” forms of production. Handmade goods are believed to represent slower lifestyles that are in tune with not only nature, but also human relationships. Somewhere along the way, the argument was also made that handcrafted goods were not only aesthetically and morally superior, but would also last longer and function better.

As a result, modern companies are caught in a double bind. They need to use industrial production in order to be price competitive, but they also have to find ways to play into the anti-industrial value system. Some companies, such as Louis Vuitton, do this by either stretching the truth or outright lying, while other companies are a bit more artful. Crockett and Jones, for example, labels their two lines as being benchgrade and handgrade, and Church’s used to call its best shoes “custom grade.” These are not terms of art. They’re catchy labels meant to imply that these products are made to custom-shoe standards. Many other brands also describe their products as “custom fit” or “bespoke quality,” neither of which should accurately describe off-the-rack garments. With so many manufacturers describing their wares as custom, bespoke, and handmade, these terms have almost all but lost their meaning.

In order for hand-craftsmanship to mean something again, we need to develop a more critical understanding of the concept. This not only means knowing more about the production process, but also knocking down some myths.

For example, there is the often-repeated idea that hand-sewn seams give garments a level of flexibility that machine-sewn ones cannot match. Is this true, however? In some ways yes, but in a large way, no. The idea comes out of the evolution of sewing machines. The earliest machines employed a chainstitch, which is a series of looped stitches that form a chain-like pattern. The problem with the stitch is that it can be easily pulled apart, and since the machines were quite cumbersome to use, the stitches were sometimes not very neatly made. Later improvements allowed machines to produce a lockstitch. Here, two threads are entwined (or “locked”) together in the hole through which they are passed. These stitches are strong, unlike chainstitches, but they lack flexibility. Thus, when they are used in an area subject to strain – such as the seat or sleevehead – they can break.

Contrast these technologies to the tailor, who can sew a backstitch by hand. This stitch loops the thread back over itself and allows the seam to stretch a bit. The result is a seam that would neither unravel like the chainstitch nor snap under strain like the lockstitch. From this, we get often-repeated idea that hand-sewn stitches are superior.

The problem with this, however, is that it leaves out some important technological advancements. There are now machines that not only replicate the hand-sewn backstitch, but also improve upon it with a complex series of looping chainstitches. Similar technological advancements can be seen in other places. Neckties, for example, used to benefit from having their spines loosely stitched together by hand. This allowed them to have some “give” when they were being knotted and unknotted, which in turn helped them retain their shape. It used to be that only a skilled craftsman could make this loose stitch, but now some LIBA machines can replicate it as well.

It’s important to recognize not only when technology has caught up, but also appreciate the complex, and at times symbiotic, relationship between machines and artisans. Machines have in many ways pushed craftsmen to develop new innovations. For example, fiddleback waists on shoes came from cordwainers who needed to invent a kind of hand-detailing that machines couldn’t replicate (see the one from Carreducker above). In a time when machine technology is so widely adopted, this was a way for artisans to differentiate themselves. Of course, I presume there will be a day when machines can replicate that easily as well, but that will just force a new round of innovation. What’s important is to recognize that machines have, at times, pressured artisans to come up with new and more refined levels of detailing. And without this pressure, we may not have seen some of the important developments in craftsmanship that we have all come to appreciate. It’s about the interplay between machines and handwork, not the battle.

So then what’s left for the modern craftsman? What’s so special about hand-craftsmanship?

To answer this, we can’t think of craft on purely practical terms. To appreciate a product for its practical qualities is to value it for its longevity, function, and design. In this world, machines will almost always dominate – their productions are more precisely made, economical, and increasingly so, durable. The advantage of hand-craftsmanship, however, has nothing to do with these interests and, in fact, shouldn’t even have to justify itself in these terms. Instead, hand-craftsmanship is about humanistic values. When something is truly handmade, we appreciate the product not just as an object, but also as a testament of the craftsman’s skill. Machine-made products can stand alone, disconnected from their makers, but handmade objects are as much about the people who made them as they are about their function.

Additionally, handcrafted goods can be valued for the artisanal dimensions. Whereas machine made goods are made perfectly and precisely, as a collection, each piece is indistinguishable from the next. Handmade goods, on the other hand, have what the authors of The Encyclopedia called “character.” They’re made with some vision of an ideal in mind, but since they’re created with human hands, there are always slight variations or inconsistencies. By being just slightly off from the ideal, each piece asserts its own individuality to the world. We don’t value handmade goods because they’re perfectly made; we value them because they’re humanly imperfect.

Philosophers such as Voltaire believed that if we could accept and value these qualities in crafts, we could learn something about life itself. It’s concretely human to strive for perfection, but fall just a bit short along the way. The pursuit of perfection, Voltaire adjured, would lead men to grief, and leave no room for surprises. By appreciating the irregularities in handmade goods, Voltaire thought we could develop more realistic expectations about life and lead happier existences.

In the end, these are the only long-term defenses for hand-craftsmanship. We should value machines for what they contribute to a product’s commercial value. They make things more economical and durable. Handwork, however, is about humanistic, artisanal, and even philosophical values. Both have their purposes and ends, but we shouldn’t confuse the two. A hand-sewn seam is not more durable than a well-made machine-sewn one, and a hand-sewn monogram on an otherwise factory-made shirt lends neither humanistic nor artisanal value. To be sure, very few things are completely made by either hand or machine, and it’s unclear when something crosses the line from being one to the other. However, we should be watchful about how the terms are used. This will not only give us a more nuanced appreciation for production, but also allow us to preserve and protect the special role for true craftsmanship.