In an old interview in the Wall Street Journal, Bruce Boyer once said it’s ironic “everyone thinks about luxury but real craftsmen are dying off.” And it’s absolutely true. Part of the problem is truly well-made things are often stratospherically expensive, which places them out of reach of most people. The other problem is that most of us rely on marketing literature for our understand of craft – and most of the time, that literature is put out by companies who have long abandoned traditional methods.

In footwear, for example, Goodyear-welt constructions are often touted as the Gold Standard. Alden says it’s “far superior to any other shoemaking method,” while Allen Edmonds says the “durability of a Goodyear-welted shoe is unmatched.” Dozens of other companies say similar things – “most reliable way to finish a shoe or boot” and such shoes “last longer than any other type of footwear.” This kind of information then gets propagated through online forums, blogs, and magazines.

For the bulk of his career, DW Frommer II has been arguing differently. An acclaimed American bootmaker, he has over forty years of bespoke shoemaking experience under his belt. He’s also an active member on various online forums – where he’s well-known for his prickly personality. He’s not exactly shy about sharing his views on things, but for all his arguing over the years, he’s also taught many people (including me) the meaningful difference between machine- and handmade shoes.

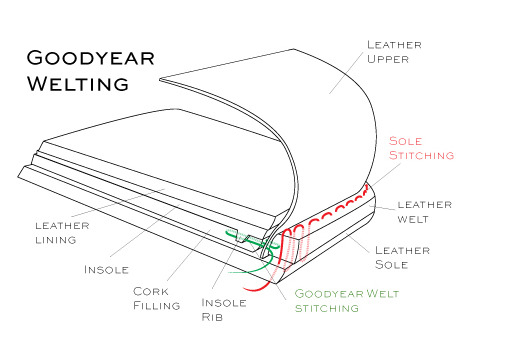

Frommer is an unapologetic traditionalist. He sees the invention of Goodyear machines as the beginning of the decline in quality shoemaking. You see, most shoes have three basic components – the outsole (which is the part of the shoe that touches the ground), the insole (the stuff between the outsole and your feet), and the uppers (the parts that surround your feet).

In traditional shoemaking, the insole functions as the shoe’s spine. A shoemaker will cut a leather holdfast into the insole, on which the uppers and welt are then attached using a shoemaker’s stitch and a special wax. This effectively seals and locks the stitching in place. The outsole is then attached to the welt, which not only firmly secures it to the uppers, but also allows for multiple resolings when needed.

In Goodyear-welted shoes, the uppers and welt are attached to the insole using a strip of canvas, which is glued (not sewn) to the insole. This saves the shoemaker effort by not requiring him to sew the holdfast to the uppers, but it also means that the canvas can come unglued, slip, or otherwise break down during the resoling process. Once slipped, it can be very difficult for a cobbler to put that canvas rib back in place – which means the soles can no longer be properly replaced.

For Frommer, this switch to Goodyear welting cascades another set of compromises. At its most basic level, instead of using good shoulder leather for the insole – which traditional shoemaker require in order to create the holdfast and secure a handsewn inseam – there’s now the financial pressure to use cheaper leather, sometimes even fiberboard, since nothing needs to be stitched on. And since the cavity inside a Goodyear welted shoe is filled with cork, the wearer never experiences the true comfort that comes from a full leather footbed – which anyone who has worn traditionally-made moccasins can attest. Even the toe and heel stiffeners are now usually made from a plastic-impregnated fabric known as celastic, which can’t be repaired when crushed (whereas leather stiffeners can).

Of course, the upside to Goodyear-welted shoes is the price. You can get a pair nowadays for as little as $200, whereas handwelted shoes generally start at $1,500 (with some exceptions, such as the more affordable Enzo Bonafe and Vass lines). Whether the ability to get a few more resolings out of a shoe – and the additional comfort – is worth the $1,300 upcharge is questionable. However, Frommer’s concerns are much broader: “I don’t want to see the craft die,” he says. “But as more people switch to Goodyear-welted shoes, there’s less of a market for handwelted ones. Even if these companies wanted to go back to traditional techniques, they can’t because there aren’t enough skilled craftsmen around. And as the demand for quality raw materials decline, so do the sources. If this trend continues, what’s going to happen in fifty years?”

A few weeks ago, I met with my friend Mark, who’s one of Frommer’s clients. He commissioned a pair of dark brown George boots (a military style shoe that’s much like a chukka boot, but features a taller shaft). They’re made from a burnishable water buffalo leather, as Mark wanted something natural and full-grain, but would also develop a lot of texture over time (you can already see some of the creasing that happened on Mark’s first try-on).

These boots are fully handwelted. Frommer channeled, feathered, and inseamed the insole by hand, then stitched the outsole to the welt and attached the heel using wooden pegs (as he feels iron nails cause a “slow fire,” rusting and rotting leather from within). The interior is also reinforced with leather heel, toe, and side stiffeners, and the lining is all seamless (notice how there’s no seam down the heel). This takes out a potential fail point in the lining, but also requires the material to be shaped by hand. Lastly, since the shoes were handlasted, Frommer was able to get a more natural curve from the top of the shoes down to the sole – following the natural off-center curve you’d see on a person’s foot (as you can see above). You can read more about Frommer’s construction technique here.

Most of us will continue to buy Goodyear welted shoes for some time. In addition to the ease of ordering, there’s also the high-value proposition on the low-end of the price scale (I’m a big fan of Meermin). I also think more expensive labels such as Edward Green, Crockett & Jones, and Alden offer some of the best looking designs around. That said, handwelted shoes are not only better in terms of quality, they also come to you in a long lineage of handcraft. In order for this craft to survive, however, consumers need to know the difference between machined and handmade shoes – just as it’s been helpful for them to understand the difference between Goodyear versus cemented constructions, or made-to-measure versus bespoke.

For more of Frommer’s work, you can visit his website. His bespoke prices start at $1,600 and (if necessary) he can conduct fittings by mail. He also teaches students at his Redmond, Oregon workshop, and has published a number of books on the fine art of bespoke shoemaking (which you can buy directly from him).