Tomorrow is August 12th, otherwise known as The Glorious Twelfth. It marks the start of shooting season in the UK for red grouse – a medium-sized, fast-flying bird that lives in the country’s heather moorlands. Although wild, red grouse populations are managed by large estates, which open their property up this time of year to hunters. Although, this year, those estates might be closed for business. Unseasonably wet weather conditions have devastated stocks – which in turn have left fewer grouse on the moors.

As you might expect, grouse hunting is not without its controversies. Mark Avery, a former conservation director for the RSPB, recently published a book titled Inglorious: Conflict in the Uplands. His argument: the intensive management that’s needed for large grouse populations – and thus larger “bags” for hunters – has damaged protected habitats, increased greenhouse gas emissions, polluted water supplies, and left downhill properties at greater risk of flooding. Plus, natural predators – including protected classes of birds of prey – are routinely killed, thus threatening other wildlife populations. With fewer predators, dense populations of grouse are more susceptible to diseases.

He also argues that grouse hunting has lost all its sport. In the past, men used to walk across hills, shooting at grouse as they were flushed out of the moors. This form of shooting, known as walked-up shooting, happened until the invention of the breech-loading shotgun, which made reloading your firearm much easier (and bigger bags more feasible). Nowadays, estates largely operate on what’s known as driven shooting, where hunters wait in small shelters known as butts, while a distant line of “beaters” walk across the moorlands to flush grouse towards them. As he writes in his recent article in The Independent:

Traditionalists decried the unsporting nature of driven shooting, where the shooter was not remotely a hunter of grouse but a mere recipient of a mass of live targets provided by the sweat and activity of the beaters. Instead of the ability to walk over rough terrain, read the ground, train your dogs and then work with them to find and shoot down a few grouse in a day – maybe 20 birds but often many fewer for a day’s exercise in the hills – driven grouse shooting allowed someone who was merely a good shot, but who lacked the broader skills of understanding the habitat, to kill many more birds.

Of course, on the other side, you have hunters who say they’re continuing a long English tradition, even if that tradition has changed, and that it’s thanks to grouse hunting that moorland is maintained and managed. Plus, their money goes to help support local economies, many of which are dependent on such seasonal events at this point.

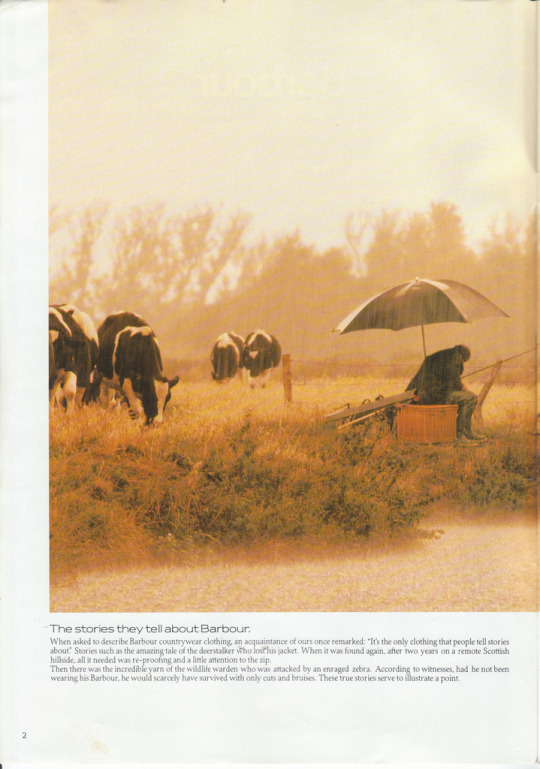

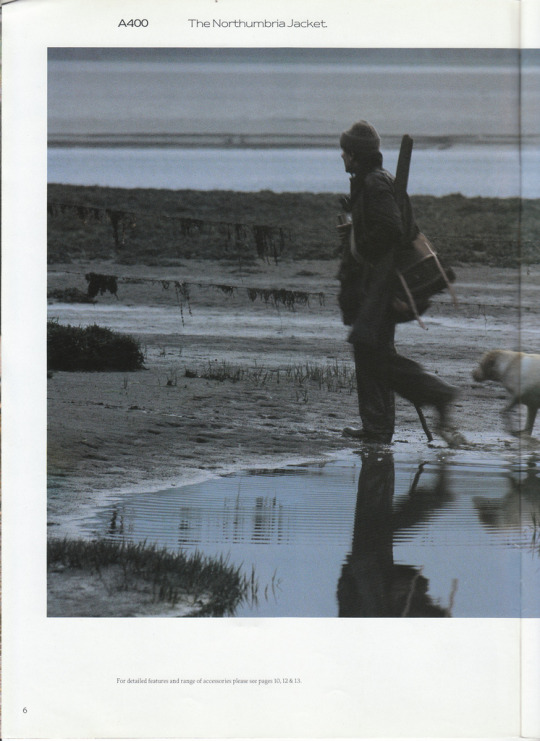

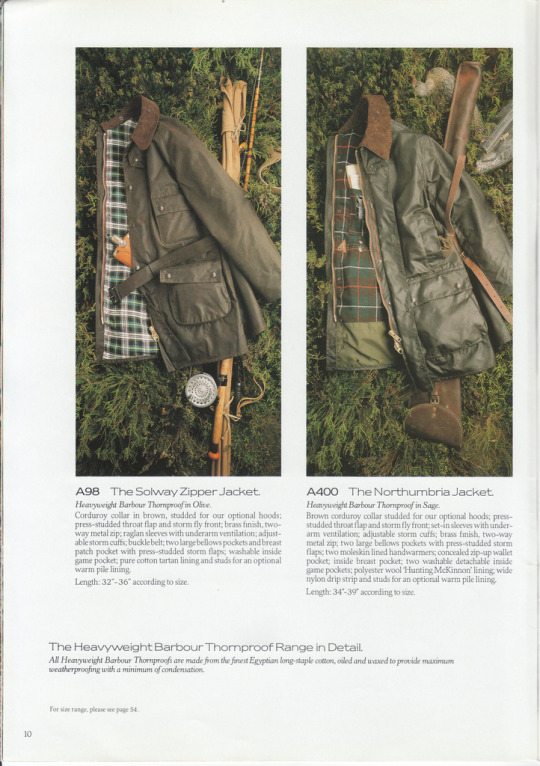

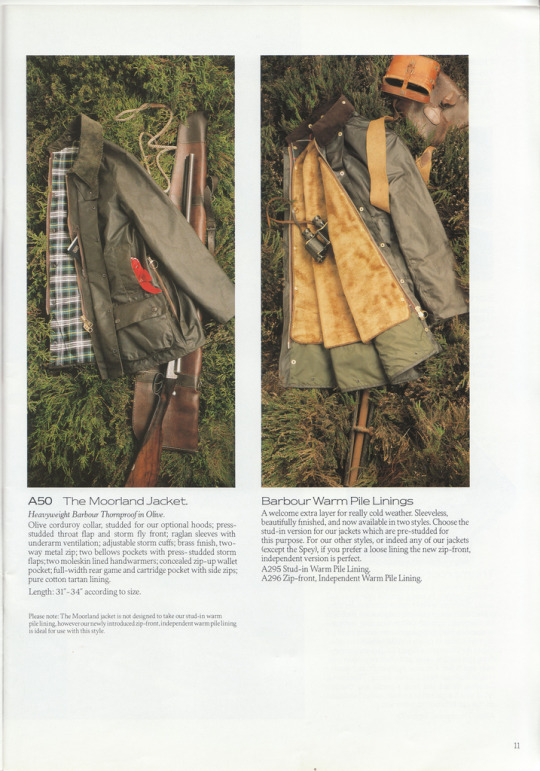

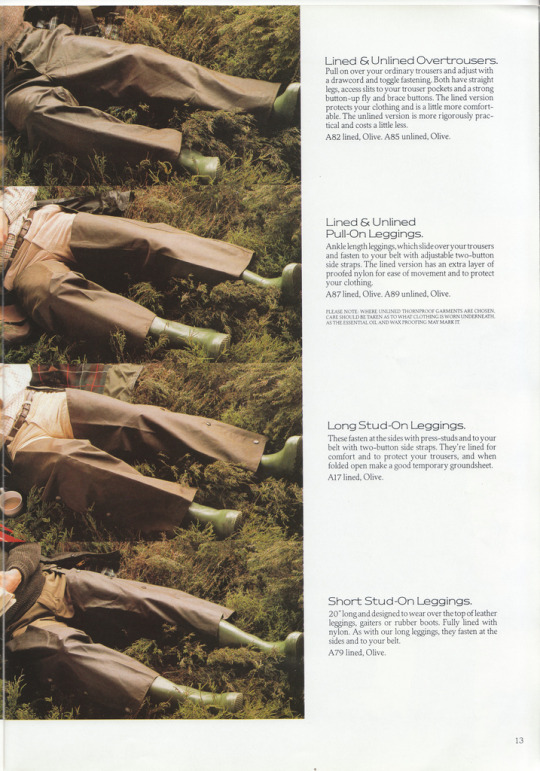

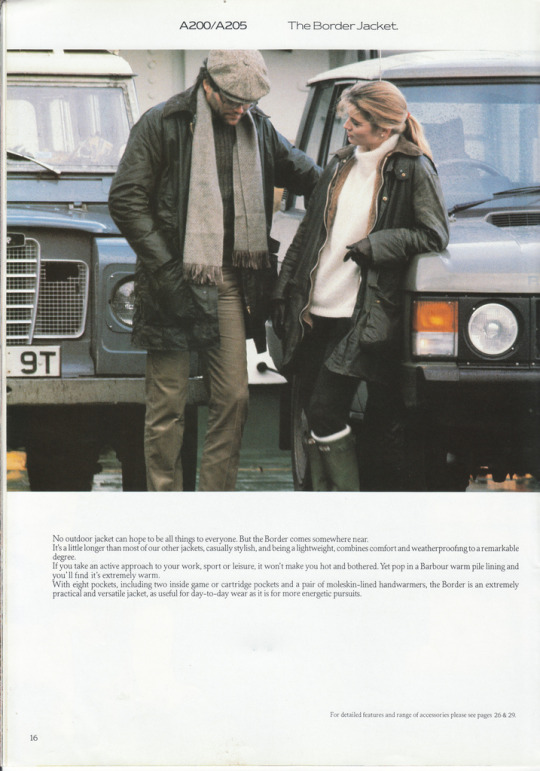

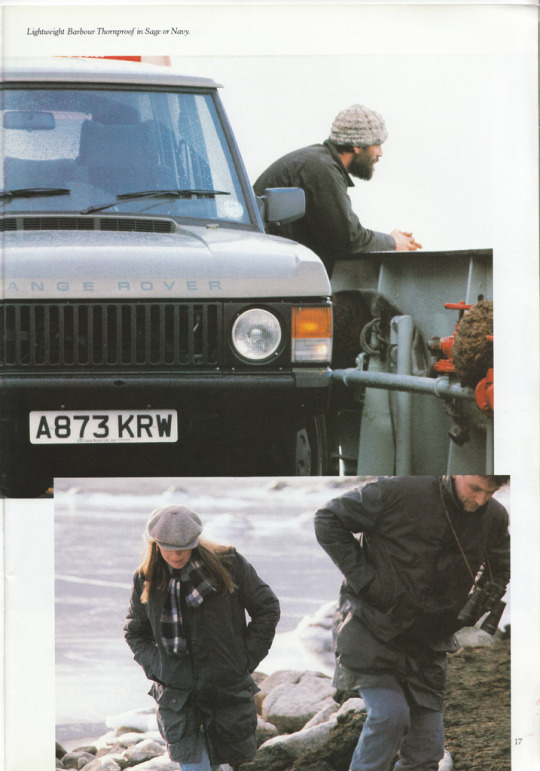

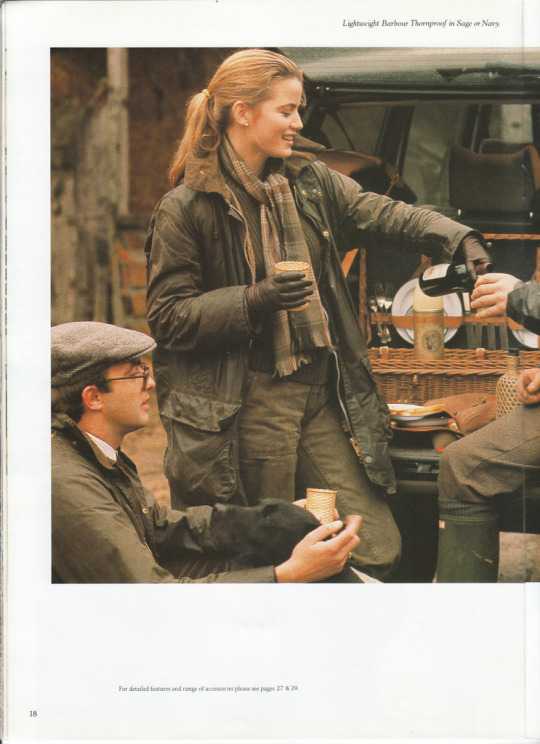

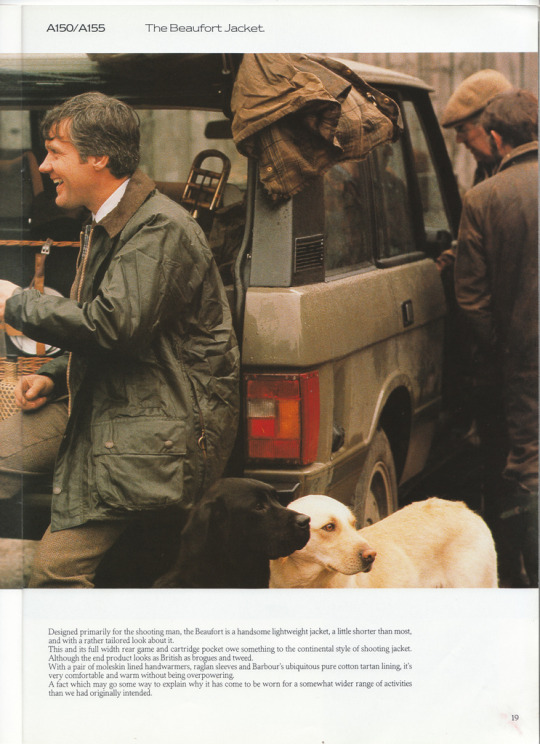

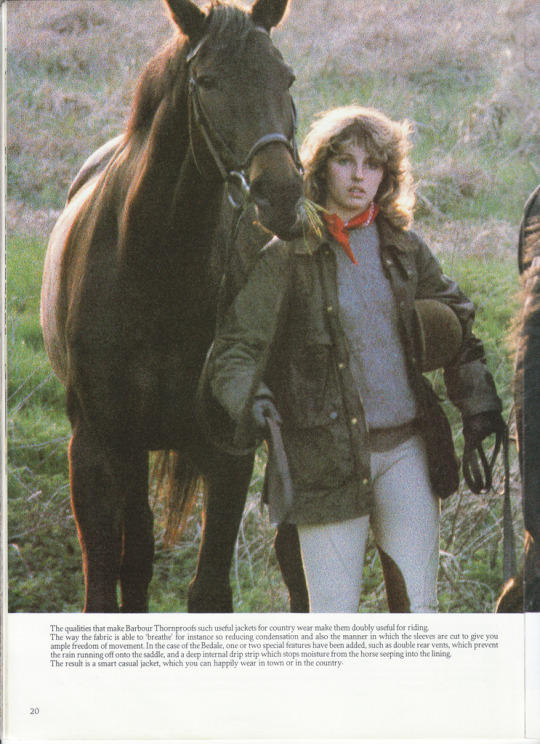

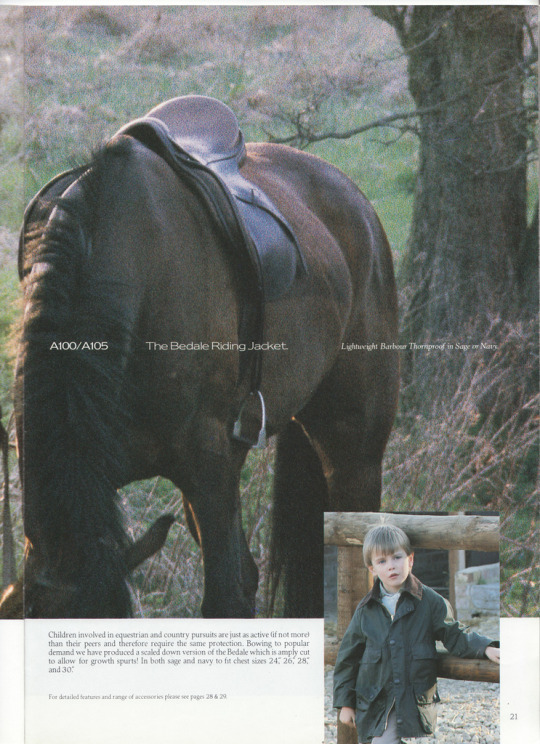

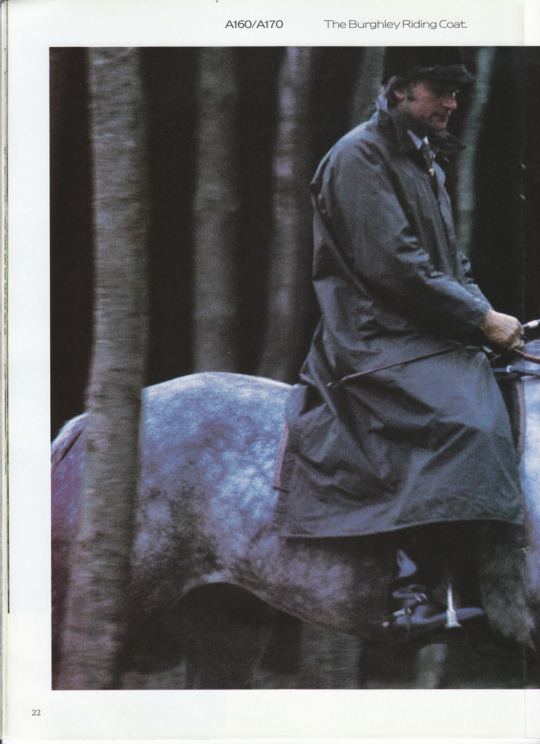

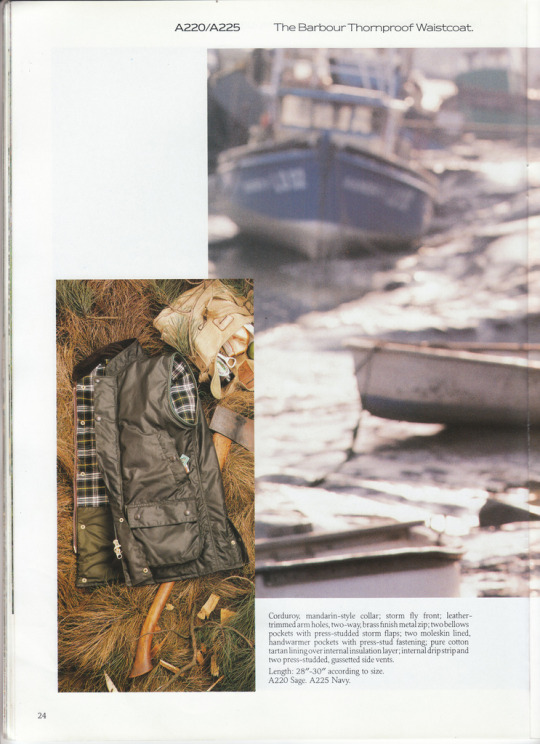

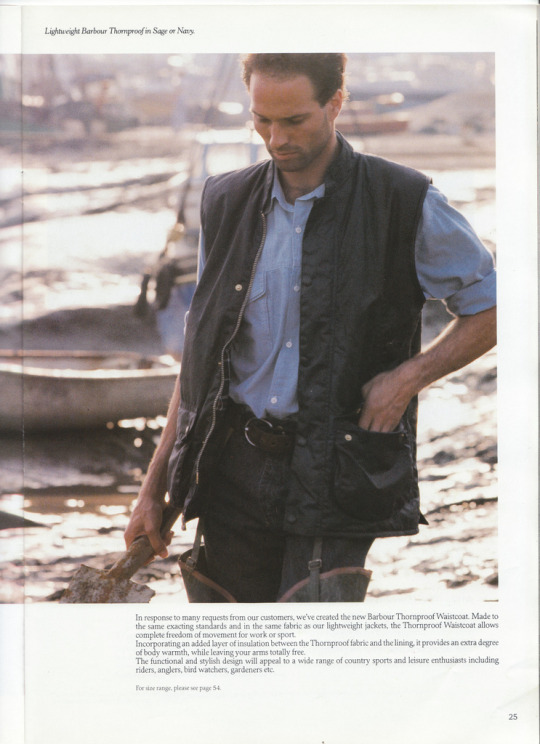

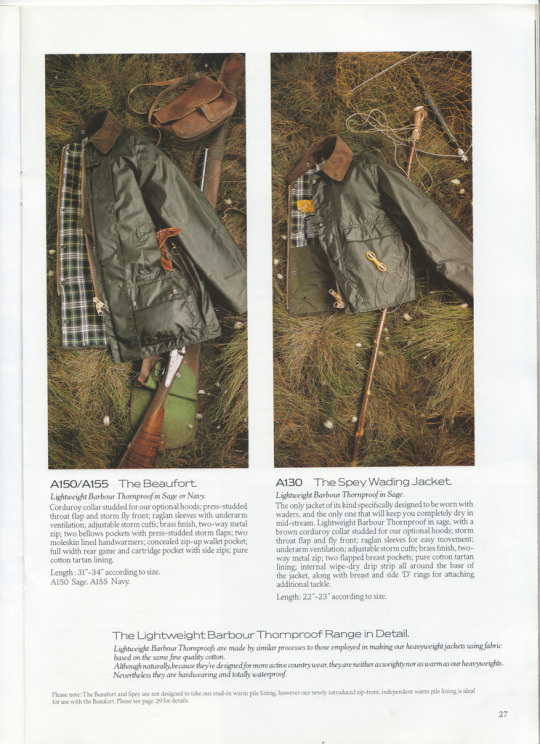

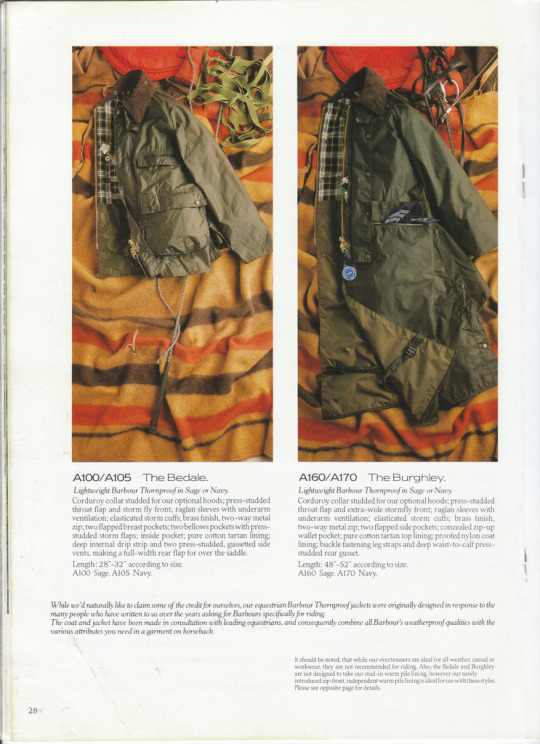

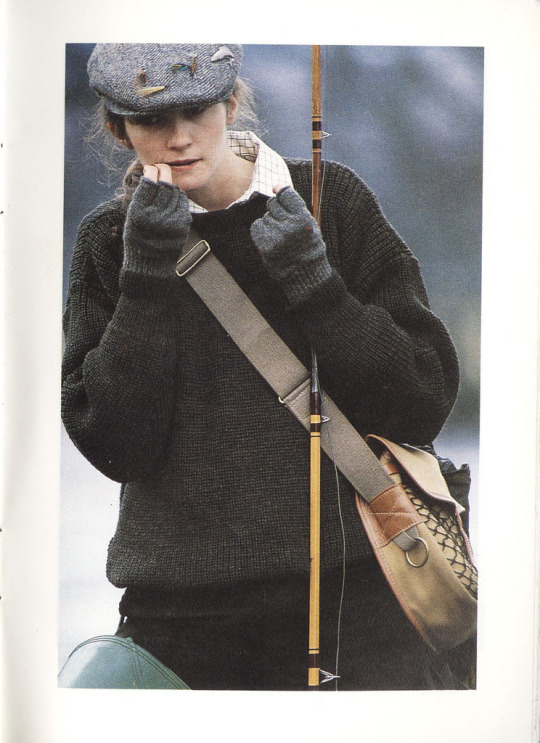

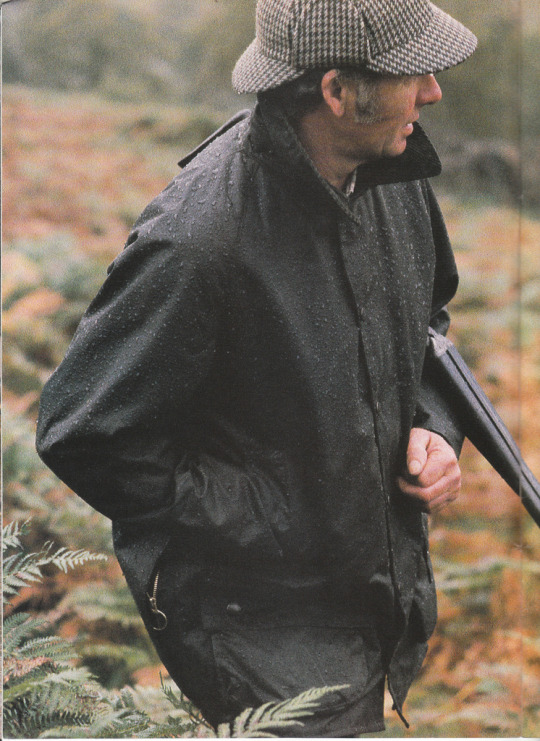

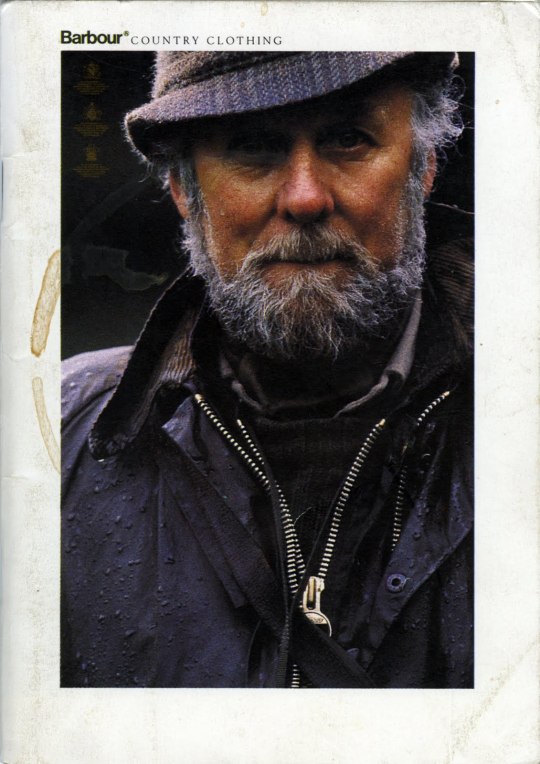

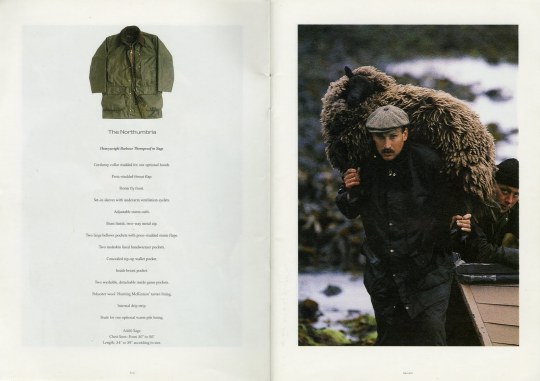

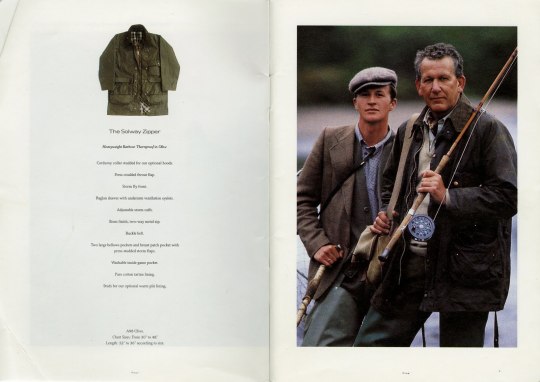

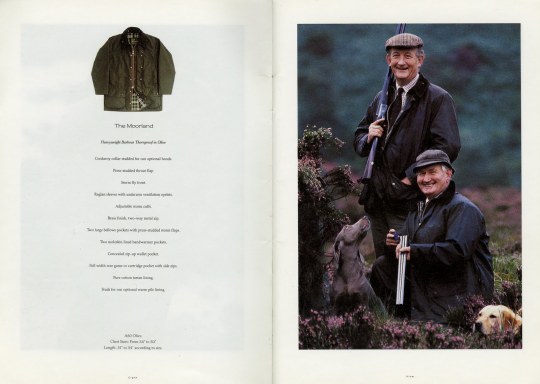

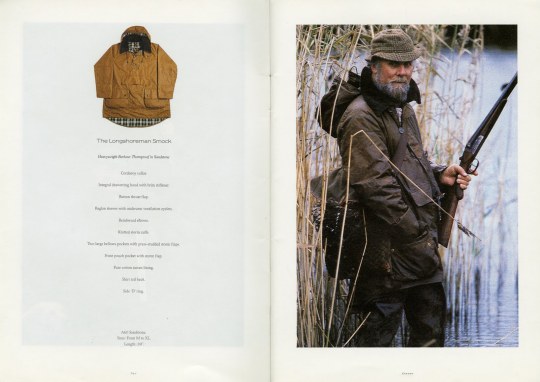

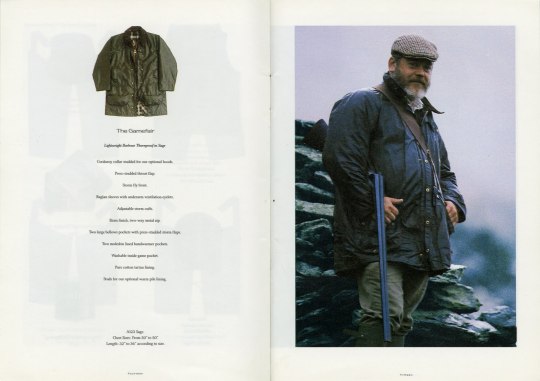

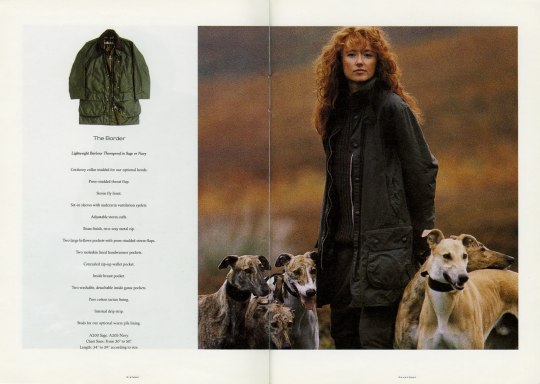

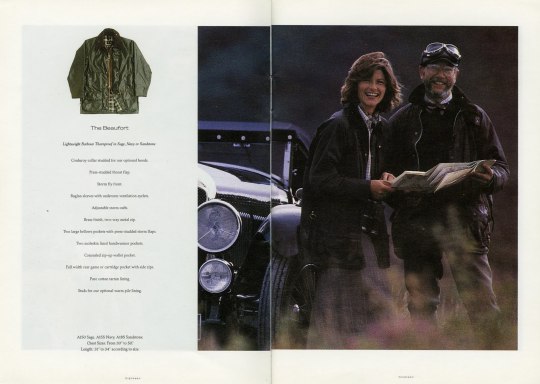

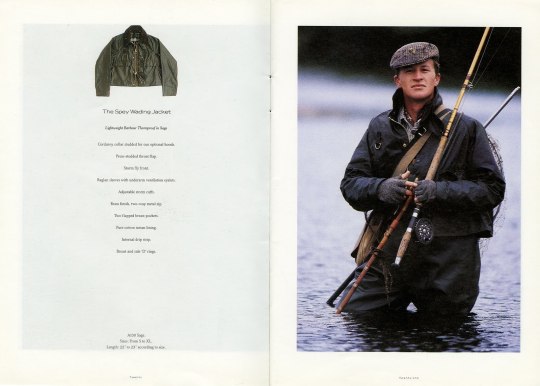

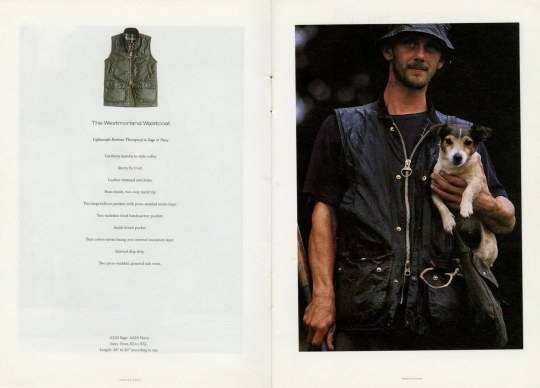

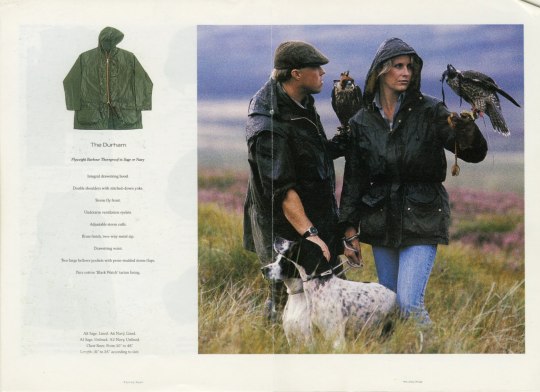

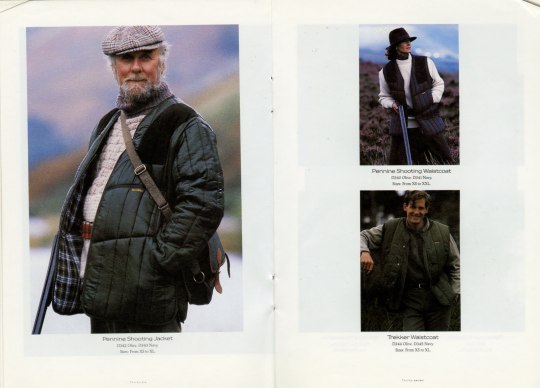

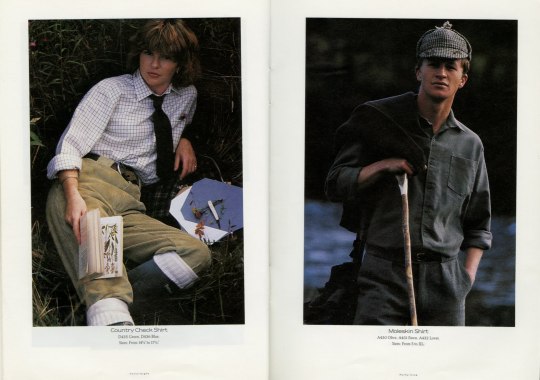

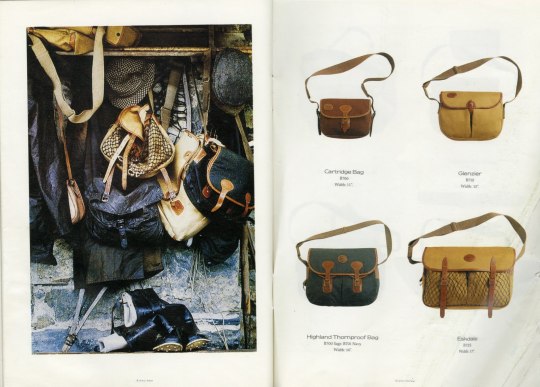

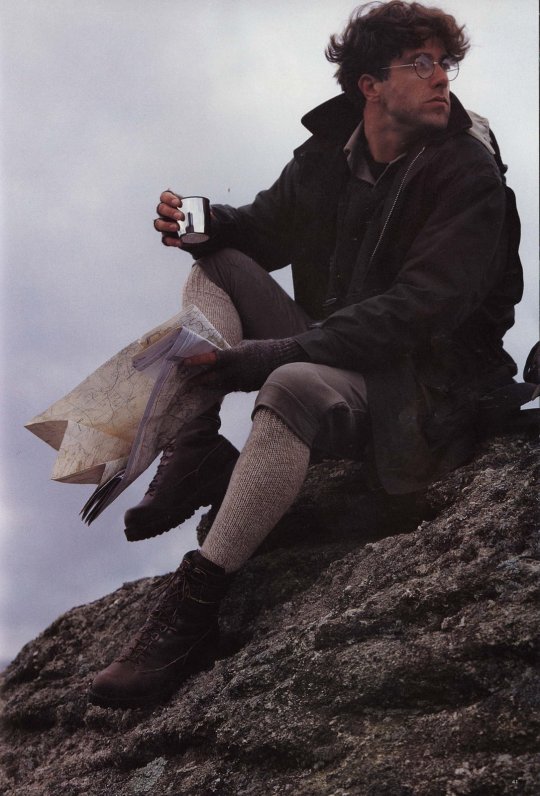

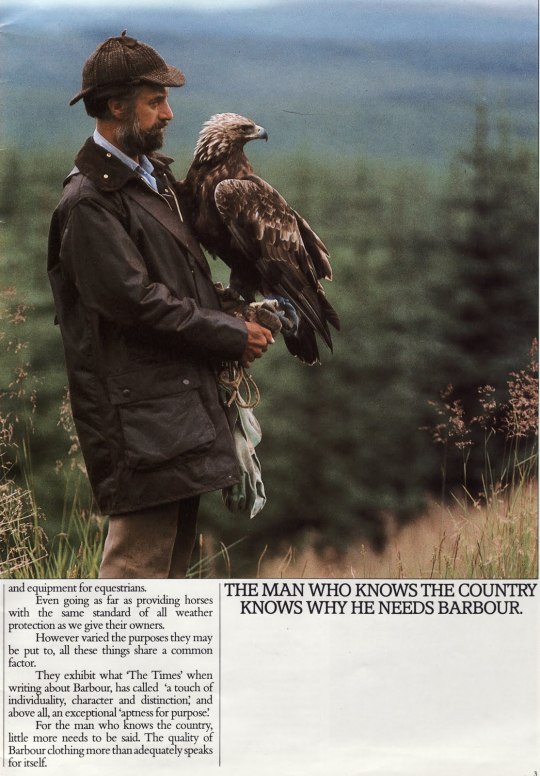

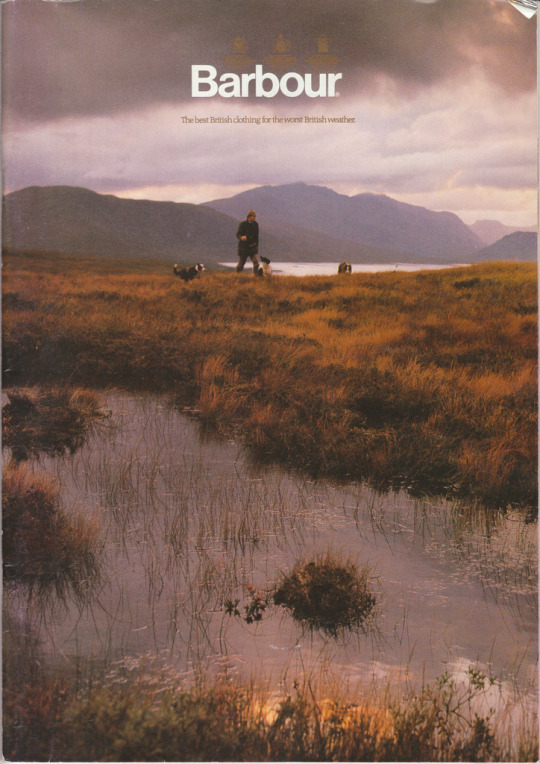

Whatever your position, here’s something we can all agree on: English hunting has given us some great clothes. Since this is a ostensibly a menswear blog, I’ll end with some old Barbour catalogs. Waxed cotton jackets thrown over heavy tweeds and tattersall shirts, these clothes hold all the romance that comes with hunting without requiring you to kill anything.