I was supposed to jump on a flight to Mexico later tonight to attend a friend’s wedding. I had the flights booked, a hotel room reserved, and a cat sitter was waiting in the wings. But like many people around the world are finding, the coronavirus outbreak has not only disrupted plans, but also changed the rhythm of daily life. Cities around the globe have instituted curfews, shut down schools, and banned large gatherings. Every regular activity nowadays feels like it comes with a new moral complication: how do you not only keep yourself safe, but also slow the spread of this virus and thus not endanger people in your community?

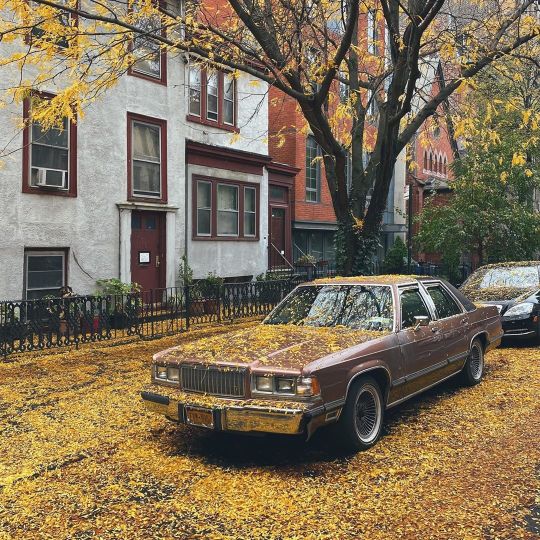

This past Monday, seven Bay Area counties issued “stay in place” orders — the strictest measure of its kind yet in the continental United States — directing all 7 million residents to stay inside their homes for the next three weeks. Businesses that don’t provide “essential” services have been instructed to send workers home. Grocers were already struggling to keep up with demand last week, but things took a turn after Monday’s announcement. Hours after the press conference, grocery stores were all but cleared out. Bins were scraped empty and shelves picked clean. The once busy thoroughfare near my home is now ghostly quiet, nearly all shops are closed, and without a daily routine, I find it’s easy to lose track of time.

So far, the focus has been, rightly, on the spread of the virus itself. But few people have discussed the psychological effects of the 24-hour news cycle and quarantine measures themselves. Here in the Bay Area, it’s too early to say what life is like under quarantine — things still feel hazy and new — but some lessons can be taken from the Toronto experience, where 15,000 residents were put on lockdown in 2003 after a SARS outbreak. Those living under quarantine were instructed not to leave their homes or have visitors. They were told to wash their hands frequently, wear masks when in the presence of others, not share personal items (e.g., towels, drinking cups, and cutlery), and to sleep in separate rooms from other household members. In addition, they were required to measure their temperature twice daily. If any symptoms of SARS developed, they were to call Toronto Public Health or Telehealth Ontario for instructions.

Dr. Laura Hawryluck, an associate professor of critical care medicine at the University of Toronto, studied the psychological effects of these measures shortly after they were lifted. In a survey of 129 people, she and her research team found a high prevalence of psychological distress and even depression. Many were angry that they were given conflicting and incomplete information, as well as frustrated by the lack of support from their public health officials and doctors’ offices. Those who had the hardest time coping weren’t just worried about their health — they also experienced anxiety over money and the health of their family members and friends. One of the biggest fears people had was that they were putting their loved ones in danger. “All respondents described a sense of isolation,” Hawryluck writes. “The mandated lack of social and, especially, the lack of any physical contact with family members were identified as particularly difficult.”

Like everyone else, I’ve been stress-scrolling through Twitter and trying to keep up with updates. I listen to the radio and check-in with The New York Times. I try to keep up with trending topics (except for when “Coronavirus II” started trending on Twitter. “Screw that,” I said to myself, “I don’t even want to know”). Consequently, I’ve found that I’ve been worrying about everything: whether my parents will abide by the quarantine, whether my community is safe, and whether restaurants and bars in my town will shutter. Yesterday, when a slew of online menswear shops started issuing discounts, I began to worry about them, too. Some of the people who will be hardest hit by this crisis were already in precarious positions: immigrants who work for hourly-wages in the food industry (some here illegally); lower-income workers without college degrees who are less likely to be able to telecommute; and small business owners who were already being squeezed by soaring real estate costs. I fear this is the actual retail apocalypse that’s been talked about.

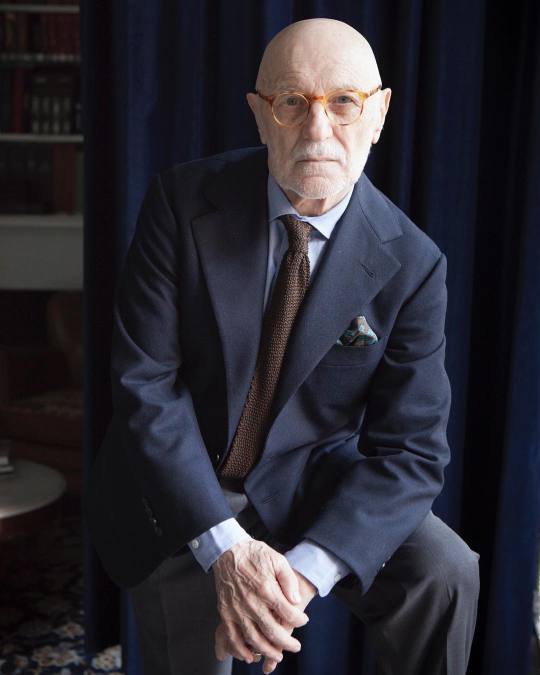

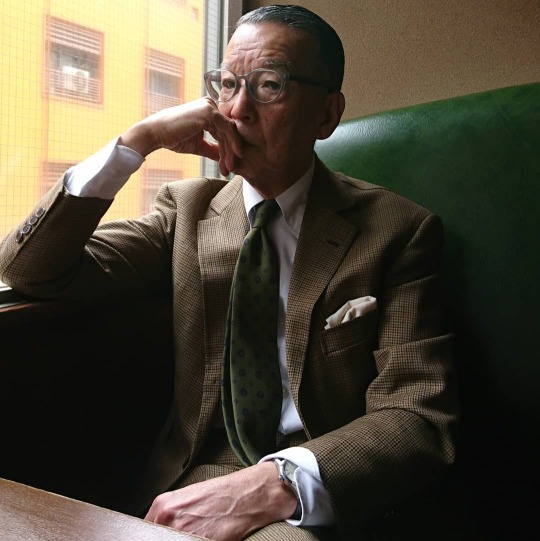

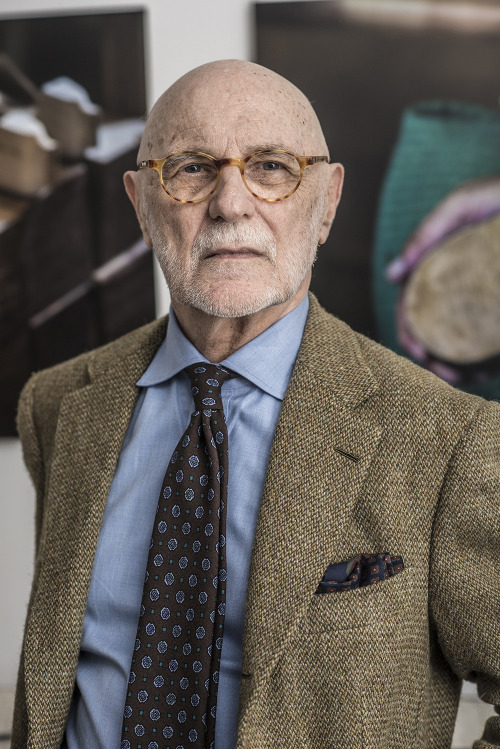

A couple of days ago, I absentmindedly opened Tumblr and started scrolling through my dashboard. As a stream of menswear images rolled down my screen, things briefly started to feel normal again. For the last ten years, menswear has been all about heritage and authenticity, but I think there’s also an important element of escapism in fashion. For a brief moment, you can look at beautifully cut-and-sewn clothes and pretend there’s an idealized place where people only live glamorous lives. You can temporarily ignore your problems and imagine a life that’s different.

Cynics and grumpy grumps love to paint consumerism as a distraction, and no area of consumerism is more superficial or distracting than fashion. To say that something is a distraction is to say that something else is more important. On the political left, for instance, there’s an ongoing debate over whether “identity politics” — what many call our basic rights — are a distraction from more pressing “economic issues” (what Marxists frame as the base and superstructure). Back in January, what seemed like an impending war with Iran was supposedly a distraction from Trump’s impeachment, which itself was supposedly a distraction from Trump’s achievements (depending on who you talk to).

There’s also a small cottage industry in the “age of distraction,” where writers can turn a profit by lamenting our lack of “mindfulness” and diagnosing the ills of our attention-deficit society. In his 1977 book titled Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, Jerry Mander argued that televisions threaten not only our personal health and sanity, but also the democratic process. Today, pundits talk about the Golden Age of manufactured consent, when everyone got their news from the same four or five TV stations. Replacing Jerry Mander’s argument about television is now the internet.

We can all stand to be more mindful. Indeed, this pandemic has highlighted what truly matters: spending time with friends and family (and, if you have them, pets). At the same time, there’s something calming about being able to distract yourself when necessary. In 2006, a team of researchers at the University of Medicine of New Jersey found that video games can help lower anxiety in children before they head into surgery. “Distraction is a pleasurable and familiar activity that provides anxiety relief, probably through cognitive and motor absorption,” they wrote. The children’s hospital at Stanford also uses video games as a way to help administer anesthesia in anxious, young patients.

Recently, I’ve decided that I have to distance myself from the 24-hour stream of bad news. I can’t keep stress-scrolling through Twitter trying to find bits of additional information, which I can’t even act on. The activity induces too much anxiety. I also find that it helps to have some sort of routine. Yesterday, Avery Trufelman, the podcaster behind Articles of Interest, tweeted: “Clothing feels so potent right now. Dressing has been a surprisingly difficult way to claim some dignity each day.” I don’t want to make too much of clothing, but being able to escape a little bit in the morning by still getting dressed, rather than laying around in pajamas, and scrolling through menswear posts has helped ease things. Sometimes distractions are good.