Those who heard Harry Hosier speak found him hard to forget. During the American Revolutionary War, Hosier, who’s better known as Black Harry, was a newly freed slave and an illiterate exhorter. In 1780, he met one of America’s founding bishops, Francis Asbury, who was traveling through the states to convert people to Methodism. At the time, Asbury needed someone to help drive his carriage, so Asbury hired Hosier, then a freedman, to travel with him. However, when Asbury noticed that his illiterate guide could recite long passages verbatim, he trained him to be a preacher in his own right.

At first, Hosier was supposed to just help bring black audiences to Asbury’s Methodist sermons. In his journal, Asbury wrote: “If I had Harry to go with me and meet the colored people, it would be attended with a blessing.” But in 1781, when Hosier gave his first sermon — “The Barren Fig Tree” — to a black audience in Virginia, his delivery was so effective and affective, even white audience members were moved to tears. Among the people in attendance that day was Benjamin Rush, a civic leader and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Rush determined it was one of the best sermons he had ever heard. “Making allowances for his illiteracy, [Hosier] was the greatest orator in America,” he later wrote.

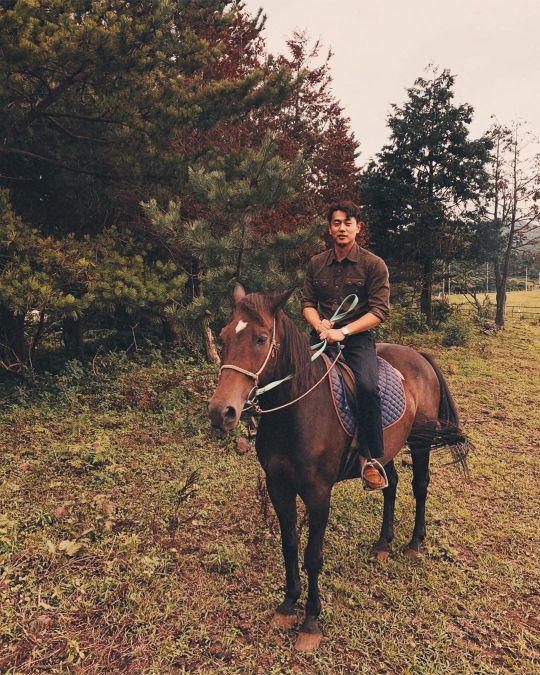

Together, Asbury and Hosier helped spread Methodism throughout America, as well as set up what would become one of the oldest American traditions: the traveling tent ministry. In the early days of the United States, it didn’t make much sense for ministers to set up a church. The souls they wanted to save were on the move, and people were continually pushing westward. Boomtowns that sprung up overnight were just as likely to go bust the next day. So staunchly devout men of God packed whatever they could into saddlebags, and then traveled through the wilderness and into towns on horseback, preaching to whoever would listen. These saddlebag ministers, who were known as circuit riders, spoke about the Word of God from street corners and open fields, in courtrooms and people’s cabins. Circuit riders still exist today, but they’ve traded their covered wagons for motor homes. You’ll often see them on university campuses, shouting at students about eternal salvation.

Circuit riders aren’t the only holdovers from early America. This country has long been one of drifters, wanderers, itinerants, nomads, and vagabonds. There’s something deep and fundamental to the American spirit that compels people to get up and move. In a lecture that Gertrude Stein delivered in 1934 to the American W[omen’s] Club about how she wrote Making of Americans, the novelist said:

Think of anything, of cowboys, of movies, of detective stories, of anybody who goes anywhere or stays at home and is an American and you will realize that it is something strictly American to conceive a space that is filled with moving, a space of time that is always filled with moving.

In high school, friends of mine participated in another tradition connected to the perpetually circulating American energy: the tradition of freight hopping. After the Civil War, as the railroads began pushing westward, migrant workers who couldn’t afford a ticket on heated passenger cars would hop onto the cold metal freight ones. These dislocated workers, who were later known as hobos, traveled with little more than the clothes on their backs, a knapsack full of supplies, and a folded railroad atlas to guide them on their journey. As a teen, I spent a lot of time on railyards admiring a hobo artist who went by the name Colossus of Roads. Many years later, I met his nephew online, who connected me with his uncle. I had his uncle autograph my Schott double-rider.

Freighthopping can be a romantic activity, but it can also be perilous. Since train tracks are federal property in the US, illegally hopping onto a boxcar is considered to be a federal crime. When staking out a freight train, you have to beware of bulls, which is slang for the railway officers who patrol the yards. But the real danger doesn’t come from bulls or even the violent ex-convicts you may meet along the way. No, it comes from the trains themselves.

To hop aboard a boxcar, you have to run alongside it just as it’s taking off. If you’re not careful, however, you can slip, fall, and get sucked underneath the giant rolling wheels, which will dismember your legs like an electric meat slicer. In his 1908 book The Autobiography of a Super Tramp, Welsh poet W.H. Davis recounts how he lost the lower part of his right leg after jumping a train in Ontario. “Taking a firmer grip on the bar, I jumped,” Davis wrote, “but it was too late, for the train was now going at a rapid rate. My foot came short of the step, and I fell, and, still clinging to the handlebar, was dragged several yards before I relinquished my hold. And there I lay for several minutes, feeling a little shaken, whilst the train passed swiftly on into the darkness. Even then I did not know what had happened, for I attempted to stand, but found that something had happened to prevent me from doing this. Sitting down in an upright position, I then began to examine myself, and now found that the right foot was severed from the ankle. […] All the wildness had been taken out of me, and my adventures after this were not of my own seeking, but the result of circumstances.”

The trick to avoiding dismemberment? Seasoned freight hoppers will tell you: if you can count every lug on a train’s wheels while it’s moving, it’s probably going slow enough for you to jump on. Even then, however, safety is far from guaranteed.

So, given the dangers, why hop a train at all? Some do it for the debauchery and adventure, as it’s more exciting than any possible backroad route across America. It can also feel like the purest expression of freedom when you’re out on the train tracks. Others do it for the utility, as it’s the cheapest way to get from place-to-place. People hop trains to find happiness to escape or to find themselves. Many do it for the sheer pleasure of moving through the American landscape. There are parts of America you’ll probably never see unless you’re looking out from a boxcar.

The thing about train hopping is that you often end up moving in circles where you meet other kinds of wanderers. No one knows how many wanderers there are in America, but they number in the millions and come from every background imaginable. There are the traveling youths known as gutter punks, who rebel against what they perceive as saccharine lockstep culture by living as nomadic anarchists. There are also working-class wanderers in the form of fruit pickers, itinerant carpenters, and circus people. Traveling rodeo cowboys, who wander according to a schedule, go from town to town so they can make money by riding angry horses and enraged bulls. Snowbird retirees wander according to the seasons so they can live comfortably in RV trailer parks. In some of the more remote parts of America, you can also find encampments of traveling hippies and misfits who live in straggles of makeshift tents and caravans.

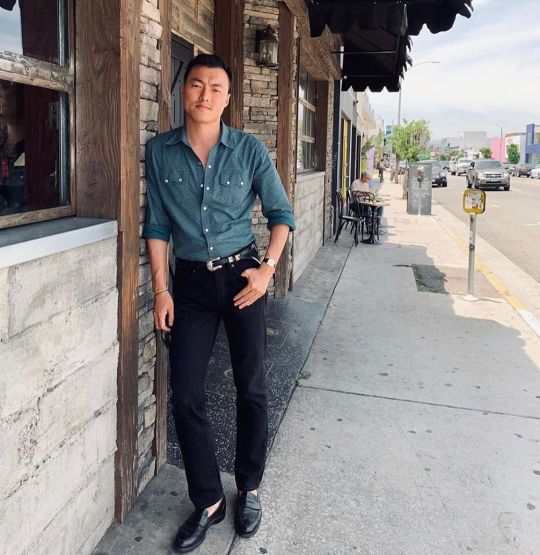

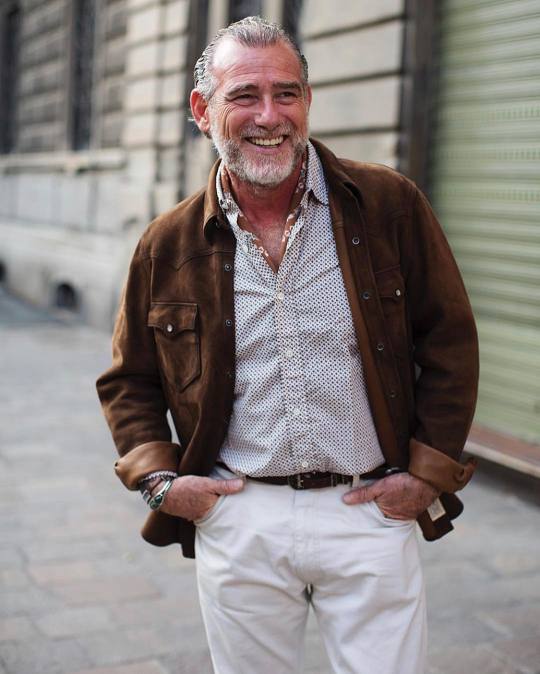

To the degree that there’s still an American uniform, it exists on the road. Across the United States, you’ll see people in five-pocket blue jeans, plain white t-shirts, and plaid flannel shirts. I’ve also been surprised to see a number of snap-button shirts while traveling. This Western-style, rendered in rugged denim or stout cotton flannel, is favored because it’s cheap, durable, and readily available. The style is worn by freight hoppers and fruit pickers, ranch hands and rodeo cowboys (even if, perhaps, only because it’s on-brand). I think of it as America’s other button-down.

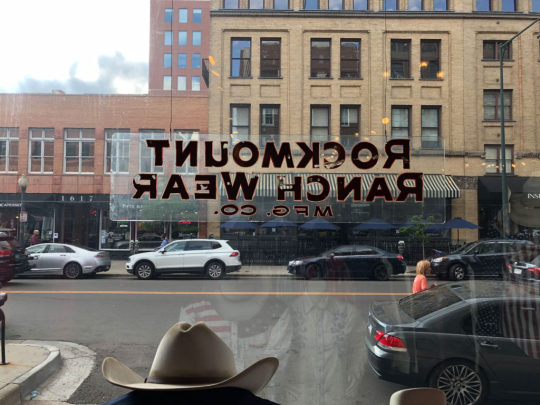

Ethan Newton, the founder of Bryceland’s in Japan, knows style well. About twenty years ago, he stumbled upon a vintage Rockmount shirt. Rockmount Ranch Wear, for those unfamiliar, is a Colorado-based company with a retail location in downtown Denver. They’re known for their wonderful blend of traditional masculinity (“we’re tough! we need shirts that won’t restrict us if we get caught on the horn of a goddamn BULL!”) and colorful, wild self-decoration (“we also need embroidery! And lots of interesting trim!”). The company claims to have invented the snap-button Western style in the 1940s when then-company-president Jack A. Weil put diamond snaps on Western-styled yoked shirts for safety and durability. “Weil took what was essentially farm workwear and glamorized it, once telling an interviewer, ‘The first thing I did was get rid of the farmer.’” Pete Anderson wrote of them at Put This On. “Diamond-shaped snaps and two-point sawtooth pocket flaps remain signatures of the Rockmount Western.”

“I’ve had quite a few vintage Western shirts, but the old Rockmounts and Short Horn Levi’s are my favorites,” Ethan tells me. “I’ve hunted down quite a few H Bar C shirts in different cloths, and some unusual rayon or wool gabardine versions from Denver Prior. I think there’s a real beauty to old Western wear, from Acme Pee Tees to Lee Westerners. There’s a lot of decorative detailing that makes them feel pretty joyous. I also like the showy elegance: a long collar point to support a printed silk tie, a higher armhole to pair with a tailored jacket, and long tails to keep it tucked in. There is a utility to them that belies their elegance.”

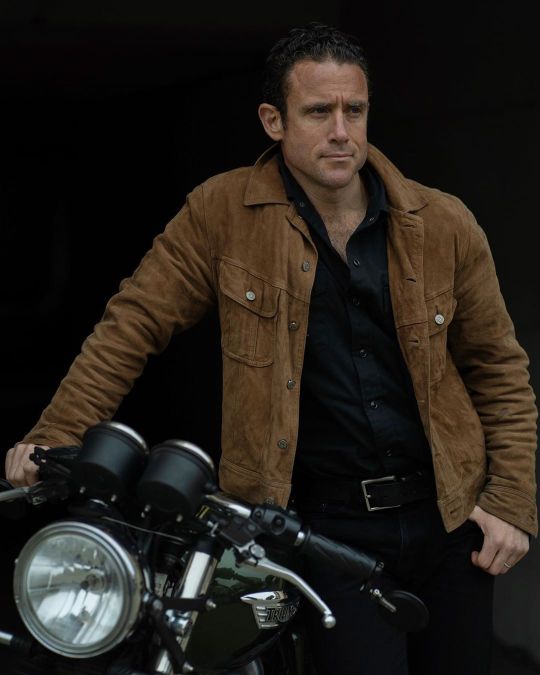

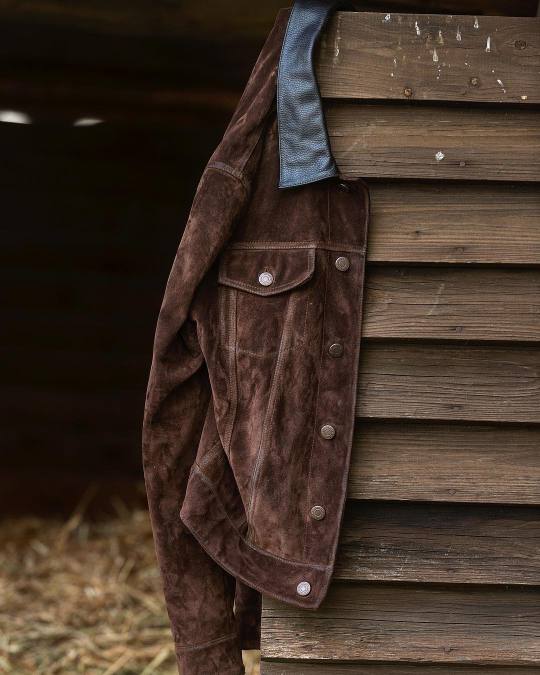

Today, Ethan makes his version, which he sells through his shop Bryceland’s. His shirts are cut and sewn in Okayama using 10oz denim, pure cotton threads, and real mother-of-pearl snap buttons. The label is also made from a pure woven rayon — a level of detail that you’d expect from a vintage obsessive such as Ethan. “I hope that if someone finds one of these in a vintage store, it will pass for a 1950s piece,” he jokes. Last fall, when I met up with Peter Zottolo in San Francisco, he was wearing a black Bryceland’s Western shirt with a pair of black COF Studio jeans and a vintage Ralph Lauren suede trucker. You could tell the fabric was thick, but after a bit of wash-and-wear, it was also comfortably broken in.

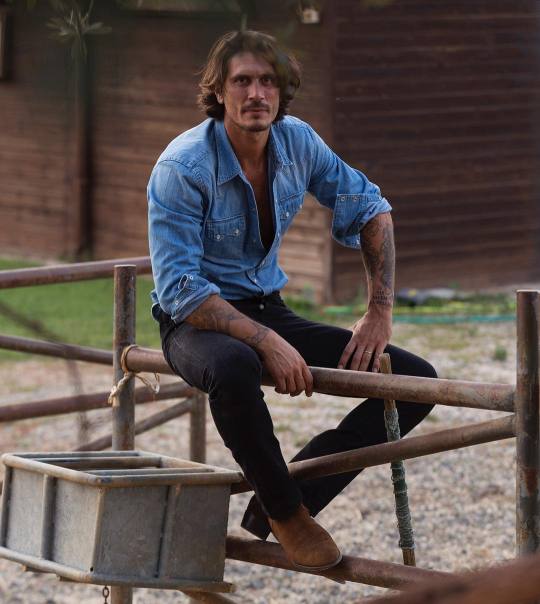

I also like Barbanera’s take on the Western-style. Made from plush velvet corduroy and printed Japanese cottons, theirs look like they’re made more for drugstore cowboys than rodeo cowboys. The style is a little softer, more contemporary, and perhaps even a little sleazy. The Western yoke, black diamond buttons, and metal concho button give you the echos of Western wear without being repros (I recommend sizing up, as they run quite slim). “I love cowboy style, but adding a Western-inspired piece to your look doesn’t mean you have to look like a cowboy,” says Sergio Guardì, one of the two Italian brothers behind the brand. “It’s about mixing influences. I wear Western shirts with jeans, Western boots, and a tailored topcoat. They also go with suits and loafers.”

Barbanera’s shirt reminds me of the Western styles I used to see on the Hollywood boulevards — ranch inspired, but fashion-forward. So it’s no surprise that many of Sergio’s Western-style heroes also come from the film industry. “Gregory Peck, who was one of the most elegant men ever, wore Western shirts in a unique way. There are also amazing photos of Pier Paolo Pasolini in the style. To me, he’s even more iconic than John Wayne when it comes to Western style because he starred in films where the style was ‘dirtier’ and more realistic. I love the costumes in Spaghetti Westerns. The pants were a bit tighter, the boots were made from suede, and there were always these great shirts. I also admire the style of my friend Mark Maggiori, who is one of the most important Western artists around. He mixes Western style with vintage workwear, suits, boots, and loafers. Barbanera’s, of course.”

I bought my first Western denim shirt a couple of years ago. At first, I was worried about looking like I’m in costume, but I’ve been surprised by how often I reach for them. Subdued varieties, such as those from Proper Cloth, pair naturally with tailored tweeds and casual suits. It’s a combination that Ralph Lauren himself has championed for decades. I also wear Western shirts with jeans, five-pocket cords, and olive fatigues. For a more directional look, you can pair them with waxed ranch jackets and cowhide double riders. But for the more conservative among us, snap buttons still look at home with Rocky Mountain Featherbed down vests, Barbanera suede truckers, and Kanata Cowichans. “For me, the Western shirt is one of the most versatile shirts I own,” adds Ethan. “You can wear it casually with faded jeans and Chuck Taylor’s, or open-necked with a Shetland or Harris tweed. Despite its detailing, it feels decidedly un-fussy. It’s a good blank canvas for a style and, like the perfect leather jacket, a lifetime purchase.”

My Western shirts are from Kapital, Barbanera, and Wrangler (the last is the most affordable option in this post, clocking in at just $30). I also really like Bryceland’s design, which has a longer point collar that looks both retro and masculine. Joe McCoy made an unapologetically sleazy version this season from plush velvet, although it seems to be sold out (their regular version in denim is excellent, however). Stevenson Overall Co. probably gets the award for having the most interesting yoke and pocket flap design.

More basic varieties can be had from Levi’s, Levi’s Vintage Clothing, and RRL. Proper Cloth offers dressier, made-to-measure Western shirts in any of their fabrics (I recommend waiting for their washed denim specials). Freenote’s single-sawtooth shirts are cut-and-sewn from an indigo Wabash-striped cotton. Lastly, Iron Heart’s ultra-heavyweight flannels come in both work shirt and Western varieties (you can find them at Division Road, a sponsor on this site, along with Canoe Club, Self Edge, and Rivet & Hide). There’s something oddly satisfying about how their snaps feel when you unbutton their shirts. The 12oz, triple-brushed fabric is so thick that, when combined with the snap buttons, the shirts feel indestructible. If you ever illegally hop aboard a frozen freight boxcar, those are the ones you’ll want to wear.