Yesterday marked the beginning of a new year on the Gregorian calendar. While seasons and days have their natural demarcations, the division of years is a totally artificial, man-made boundary. Humankind needs some way to clear the books and start a new ledger; somehow we have jointly decided that the time to do this is the turning of the new year, and that this happens on an agreed-upon day in the dead of winter. The Earth recognizes no particular difference between Tuesday and Monday, but by now billions of new year resolutions have been made, some already broken. This year, we tell ourselves, will be the year that we become better versions of ourselves.

Fashion, too, reinvents itself on a schedule. Every year brings new clothes, new trends, and even new companies. 2019 will offer hundreds of options for every imaginable item that could be in a closet, each evolution differing from its predecessor only by a matter of degrees. Hanes is for basics. American Apparel is Hanes, but pornographic. Everlane is American Apparel, but celibate. Entireworld is Everlane, but cultish.

Though the market drowns in options, and the stream of fashion moves ever quicker, the average consumer does not navigate the twists and torrents of the entire industry. Instead, they find direction from just a handful of companies. And what matters is not the passing of seasons or the deluge of new releases, but rather how each company organizes those releases that affect our perception of time – and, relatedly, style.

The Original Timetable

Let’s start with the most basic unit of time in the modern fashion system: the seasons. There’s a natural ordering of time in fashion that’s simply practical and tied to weather. Soon, the landscape will quietly explode with colors and it’ll be time again for songbirds, meaningless baseball, and cold pilsners sweating on picnic tables. We’ll wear camp collars again, and after a few months more, pull out sweaters to brace for the cold.

But fashion respects other calendars too. As I mentioned in an earlier post, our modern production system was organized sometime in the 17th century. We take it for granted that France today is synonymous with fashion, but this wasn’t always the case. Taste tends to follow power, and when Louis XIV took the throne, the world’s style capital was Madrid. In Spain, the elites wore tight and rigid clothes, often dyed black (which was not only an expensive color at the time, but also considered to be sober and dignified by the Catholic Habsburg monarchy).

During this time, the French mostly imported their luxuries. Their fashion came from Spain, silks from Milan, tapestries from Brussels, and mirrors from Venice. Louis XIV, however, sought to change all that. He started a New Deal program for French luxury makers. The industries he built around fine furniture, textile, clothing, and jewelry not only provided his subjects with jobs, but also made France a world leader in taste and technology. Louis XIV’s finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, famously said that “fashions were to France what the mines of Peru were to Spain,” noting the lucrative export opportunities this created for the country. As Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell writes in The Atlantic, it was an unbeatable economic stimulus plan – and it helped set today’s fashion system:

One of Colbert’s most effective and far-reaching innovations was to mandate that new textiles appeared seasonally, twice a year, encouraging people to buy more of them, on a predictable schedule. Fashion prints were often labeled hiver or été for winter or summer, with corresponding props like parasols, face masks, and fans for summer; for winter, there were furs, capes, and muffs for men and women alike. Lightweight silks were reserved for summer; velvet and satin for winter. Due to the changeable French climate, there had always been a certain seasonal rhythm to the textile trade, but now it became formalized and inescapable.

We still talk about fashion today as though we’re on Louis XIV’s spring/ summer and fall/ winter schedule. But in reality, many of the bigger fashion names have at least six releases per year: pre-fall, fall, winter, resort, pre-spring, spring, and summer. Fast fashion companies, such as Zara and H&M, drop new releases almost every week. The most important measure of time in fashion today isn’t the passing of seasons. Nor is it about the deluge of options because the average consumer doesn’t even pay attention to a fraction of the number of companies on the market.

Instead, what matters is tempo. In music terminology, tempo refers to a song’s pace. Depending on the performer’s intent, a piece can be played with a slightly upbeat or slowed down tempo to affect the listener’s perception of time. In ensembles, the tempo is set by a conductor or one of the instrumentalists, often the drummer. In electronic music, it’s known as beats-per-minute (or BPM). When a song has a high BPM, we feel time is moving faster. When it’s slow, we feel time is slowing down. (At my old job, there was an Italian restaurant across the street called Adagio, an Italian word for slow, which seemed like the worst name for a service-orientated business. Unsurprisingly, that restaurant is now closed).

The current fashion system, which has new releases every week, if not every day, is shaping our conception of time and style. You don’t have to pay attention to the flood of new releases on the market, even a narrow focus on just one company can make you feel like the pace of fashion is quickening because new items are constantly being released.

Some of this is about how streetwear has influenced the broader fashion market. The idea of a weekly and supposedly “limited release” drop has become almost natural for almost any fashion brand. When I spoke with the owner of a classic menswear shop last year, he said that he’s planning on reorganizing his business so that each week has a dedicated drop – a safari jacket, a tweed, or a unique pair of shoes. Once that week’s drop passes, it’s on to the next product. The center of fashion production today isn’t on manufacturing, but rather marketing. Isabel Flower at Grailed writes:

Not by coincidence, the drop is historically synonymous with the rise of streetwear, and pairs the promise of rarity with the fanatical brand allegiances that have come to define conspicuous consumption over the past 30 years. Now that the entire fashion industry is studying the logistics and the ethos of streetwear’s extraordinary ascension, limited production runs, spontaneous releases and “one-chance-to-buy” mania are staple sales strategies. Luxury retailers from Barneys, to Colette, to Dover Street Market are using the drop to generate urgency and specificity. […] Manipulating the supply chain by carefully discharging restricted quantities helps brands disguise the fact that it is now actually very easy and cheap to make things.

It would be too easy to lay the blame on streetwear, however. The real culprit of fashion’s quickened tempo is about the rise of fast fashion. The fast part of the term refers to how quickly a company can bring runway looks to market. To be sure, cheap clothing has been around forever, from Levi’s to Dickies to Hanes. Fast fashion isn’t just about cheap clothing, but rather about giving consumers access to the latest and hottest looks.

These fast fashion houses rely on just-in-time manufacturing, ICT-enabled inventory systems, and a wellspring of creativity that exists outside of the companies themselves (they copy, in other words). They’ve managed to collapse what is normally a six- to nine-month production cycle into a matter of weeks. And, as those deliveries hit shelves, new designs are always around the corner, making the latest releases almost all but obsolete. Brands that sit upmarket have had to respond accordingly. A few years ago, companies such as Tom Ford and Calvin Klein toyed with the idea of a “see now, buy now” model, where consumers could purchase clothes just moments after they debuted on the runway. This was an effort to cut fast fashion brands off at the pass, before they had a chance to copy, and capitalize off the quickened pace of today’s fashion marketing.

Neophilia

In his 1721 book Lettres Persanes, Montesquieu lamented that fashion moved too quickly for him to capture it in writing. “What is the use of my giving you an exact description of their dress and ornaments?,” he cried. “A new fashion would destroy all my labor, as it does that of their dressmakers, and before you could receive my letter, everything would be changed.” Even back in the 18th century, people in the clothing trade relied on neophilia – the love of the new – in order to sell the wares. It wasn’t called neophilia back then, of course, but even people three hundred years ago got bored with old things easily and became fascinated with the novel.

The changing tempo of fashion, however, has completely warped our sense of what can be considered new. In her essay “The Fashion Timescape,” Federica Carlotto writes: “The frantic spiraling up of the fashion rhythm seems to annihilate the essence of fashion, that of novelty: the increasingly faster replacement of the ‘new’ with the ‘newer new’ is eventually forcing both ‘news’ into a flattened co-existence. In this scenario, neophilia itself seems to be heading for implosion.”

The new system has some big costs. By compressing the regular fashion cycle into a two or three week span, consumers get bored much too easily and companies can’t be bothered to make something sustainably. The quickened tempo has also shortened the window of opportunity for companies to capture profits. Production cycles must turn faster, which squeezes labor and generates alarming environmental damage.

The new tempo is also draining fashion of the very creativity that makes it interesting in the first place. Before he quit Dior, Raf Simons spoke to Cathy Horyn about how today’s fashion industry doesn’t allow enough time for a serious artistic process. “When you do six shows a year, there’s not enough time for the whole process,“ he told her, not defending the system but, rather, stating the reality that now faces high-fashion houses. “Technically, yes — the people who make the samples, do the stitching, they can do it. But you have no incubation time for ideas, and incubation time is very important. I have no problem with the continuous creative process. Just now, while waiting in the car, I sent four or five ideas to myself by text message, so I don’t forget them. Ideas are always coming, but they’re stupid things.”

Ways to Slow Things Down

This system clearly doesn’t work. It’s making consumers unhappy with their purchases before they even get them, draining designers of time to create actually worthwhile things, and having enormously negative impacts. However, there are healthier ways we can interact with fashion. One obvious strategy is to stay close to the classics – a navy sport coat, grey flannel trousers, oxford button downs, and blue jeans – but there are also ways to slow down the tempo of fashion without leaving fashion entirely.

Hedonic Elevation

Much of what I love about fashion today is as much about process as it is about products – I love to hunt for the right item, read about things on blogs, and participate in online communities. Federica Carlotto suggests consumers can add another dimension she calls “hedonic elevation,” which is basically a fancy term for waiting.

The best example of this is Supreme, whose consumers are willing to queue up for hours, sometimes even camp out, just for the chance to buy something at one of their stores in London or New York City. “Pre-purchase waiting, especially for high-end products, provides consumers with a greater sense of excitement than the actual act of purchase,” Carlotto writes. “In the case of Supreme, the act of waiting generates a temporal space where the consumers live in the pleasant anticipation of the purchase. In addition, the fact that the waiting happens ‘in queue’ somehow elongates the process of purchasing itself, creating a bond between the waiters. They convert the potential ‘waste of time’ of waiting into a unique social event, to be remembered after the act of purchase.”

Supreme is unique in how they’re able to imbue the waiting period with meaning and they have a loyal community of consumers. Not all brands are so fortunate. More realistically, companies should think about they can make waiting periods more meaningful, particularly around purchases such as custom-made products or pre-sale purchases. Consumers, likewise, can learn to enjoy the waiting period. There are entire online forums, for example, dedicated to bespoke clothing, where participants share ideas for new commissions, drawing out the ordering process and filling the time with meaning and excitement. Not everyone has the time and budget to buy bespoke clothing, but the principle is the same – there’s a certain pleasure in the long process. Find ways to make your purchases be about more than the items themselves.

Shop Vintage

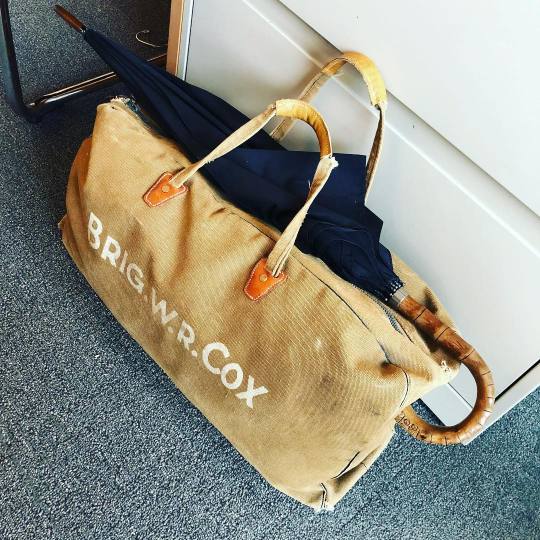

Rummaging through a thrift store is not only a great way to score a deal; it can also be a way to find things you may not be able to get elsewhere – maybe a vintage tie made from hand block-printed silk, or a leather jacket that’s been perfectly beaten-up over the years. Carlotto calls it “past-iche.” In the way that neophilia feeds off the new, vintage goods enjoy a certain prestige in their solemn stillness that’s “beyond time.”

You don’t have to go full vintage, but wearing something hauled out of the back of a thrift store can be a nice way to incorporate that kind of patina and honest wear that makes these ensembles so appealing. And, if you’re a cubicle farmer like me, that sort of wear can be tough to achieve on your own. If you’re looking to get your first vintage piece, consider French chore coats, military field jackets, denim truckers, OG-107 green fatigues, thick belts, and jewelry. On hot days, when your outfit is a simple overshirt layered over a tee, a necklace with some vintage pendants, a Navajo cuff bracelet, and a silver ring can make all the difference between a mundane outfit and an interesting one.

Don’t Buy Fast Fashion

Unfortunately, fast fashion casts a long shadow over everything. Its influence is inescapable, which is why so many upmarket brands have had to adopt the same release schedule. But to the degree that you can slow things down for yourself, avoid fast fashion entirely. You don’t need to spend a fortune to look good. People have been dressing well on a budget for generations, and in modern times, that’s often meant turning to brands such as Levi’s and Converse. Develop your eye and sense of taste, don’t let price lead you astray, and raid second-hand markets for deals. Some of the best dressed people I see on the street are young people who simply have an eye for style. Vintage fatigues, Hanes Beefy tees, Levi’s jeans, plaid flannels, and sneakers can all be had for little money.

A few years ago, before he left his post at Hermes to start his own eponymous label, the whispery designer Christophe Lemaire spoke with iFashion about how the industry is changing. “Fashion now is all about spectacle,” he lamented. “I don’t mind spectacle. I think we need strong images. But when it’s only about impressing and making noise in order to exist in the media, I think we lose the real point. If man loses relationship to time, it gets crazy.” This year will surely introduce a whole new set of trends, some good and some bad. There’s nothing wrong with participating in trends, but beware of how the tempo of fashion is changing your notion of novelty.